Many remember the 1980s as a decade characterised by the HIV and AIDS epidemic – a fatal virus that wreaked havoc upon LGBTQ+ people and society at large. Shrouded with misconceptions that were often rooted in homophobia, little was understood about the virus from a medical point of view. Still today AIDS accounts for many death worldwide, and it is estimated that 35 million people have died from AIDS-related illnesses since the 1980s.

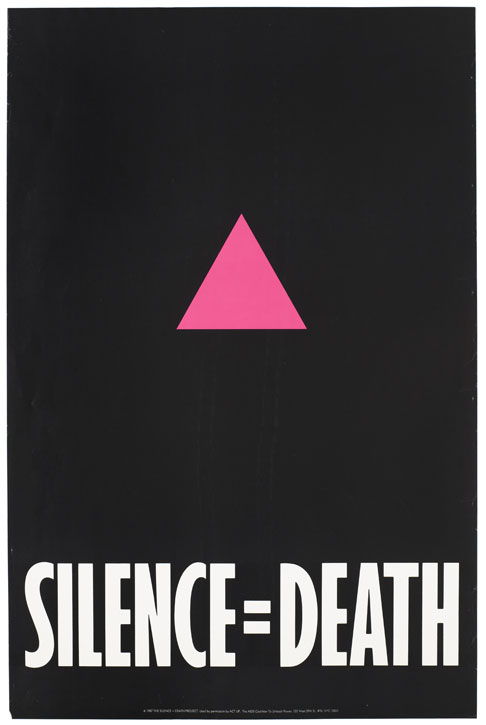

A pink triangle against a black backdrop with the words 'Silence = Death'

1987, colour lithograph by ACT UP

Centred upon the diverging experiences of masculinity across sexuality, race and religion, Barbican's exhibition 'Masculinities: Liberation through Photography' (20th February – 17th May 2020) shines a light on a generation of gay artists who lost their lives during the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s.

Although we should not wholly define these artists by their sexual orientation or death, here are some of the artists affected by AIDS who widened the possibilities for representing LGBTQ+ identities and perspectives in art.

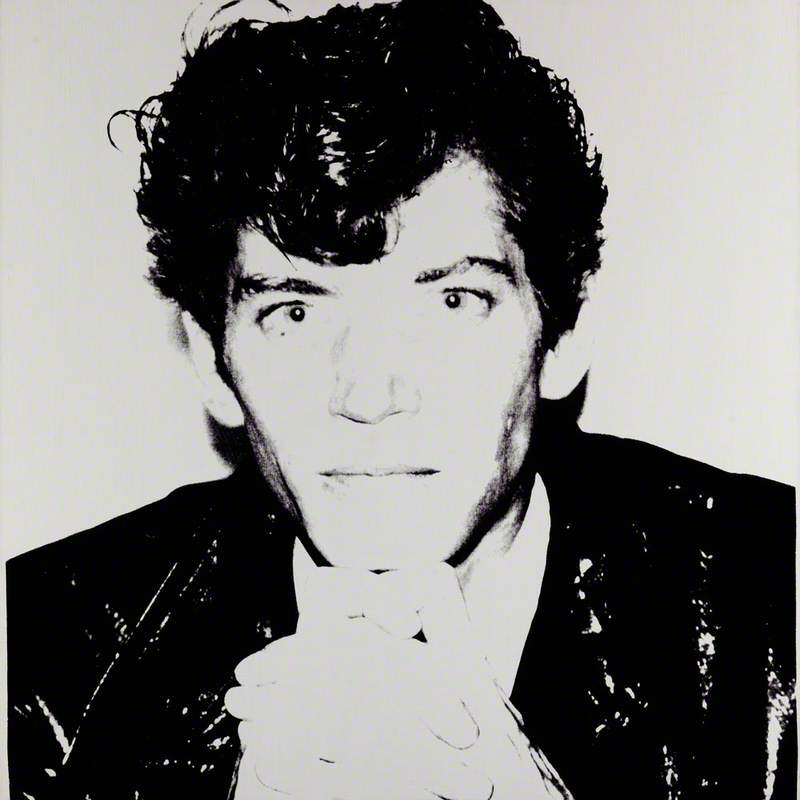

Robert Mapplethorpe

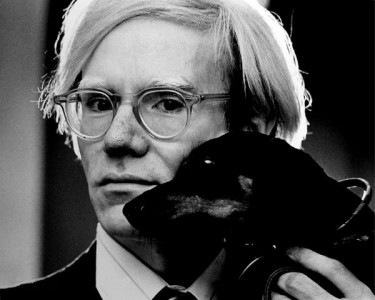

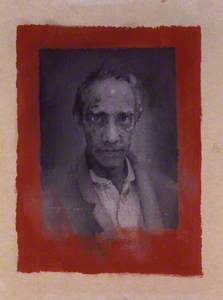

In 1983, Andy Warhol created this silkscreen painting of Robert Mapplethorpe, a pioneering photographer known for his homoerotic visions of the male nude.

Like Warhol, Mapplethorpe's artistic status grew into one of legend as he came to prominence against the backdrop of New York's sexual liberation and the freewheeling creativity flourishing in places like the Chelsea Hotel between the 1960s and 1980s. Unabashedly offering new representations of the male body and queerness – sometimes shocking his contemporaries by conflating religious insignia with explicitly sexualised nude photography – Mapplethorpe embodies the LGBTQ+ and BDSM subcultures of his era.

After the outbreak of AIDS in the late 1970s and early 1980s, figures such as Republican senator Jesse Helms regarded the virus as a 'punishment' for homosexuality, a view shared by many at that time. In 1989, Mapplethorpe's work was censored by Helms, who, alongside 100 Congressmen, forced the Corcoran Gallery in Washington D.C. to remove the artist's work from public view.

Mapplethorpe died on 9th March 1989 at the age of 42. He left behind an important legacy and founded the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. The foundation continues to donate funds for medical research to fight against AIDS and HIV.

Felix-Gonzales Torres

Cuban artist Felix Gonzales-Torres was a gay artist working in America. Throughout his career, he made conceptual work relating to his sexual identity and responding to the difficulties of living with HIV/AIDS. In 1991, his long-term partner, Ross Laycock, died of complications due to AIDS, which led Gonzales-Torres to create some of his most memorable works. Below is a recent instalment of his, Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), created shortly after his partner's death.

Comprised of 175lbs (nearly 80kg) of wrapped sweets that the public could consume, the amount was chosen to match the bodyweight of Ross as he began to languish due to illness. The seemingly seductive, interactive work is in fact supposed to mirror the tragic decline of his partner.

In the same year, the artist created other works that profoundly communicated the traumatic experience of losing a loved one to AIDS, seen in Untitled (Perfect Lovers) and Untitled (billboard of an empty bed), both 1991. As part of the latter work, Gonzales-Torres appropriated advertising spaces across New York and displayed large-scale photographs of empty beds. The work symbolised absence and created a powerful visual in the public space that communicated the realities of the AIDS death toll at a time when it was still a stigmatised subject.

The artist passed away due to complications arising from AIDS in 1996.

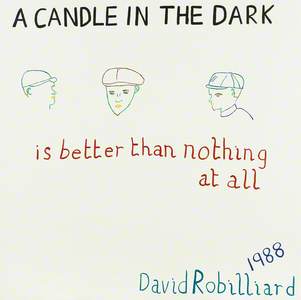

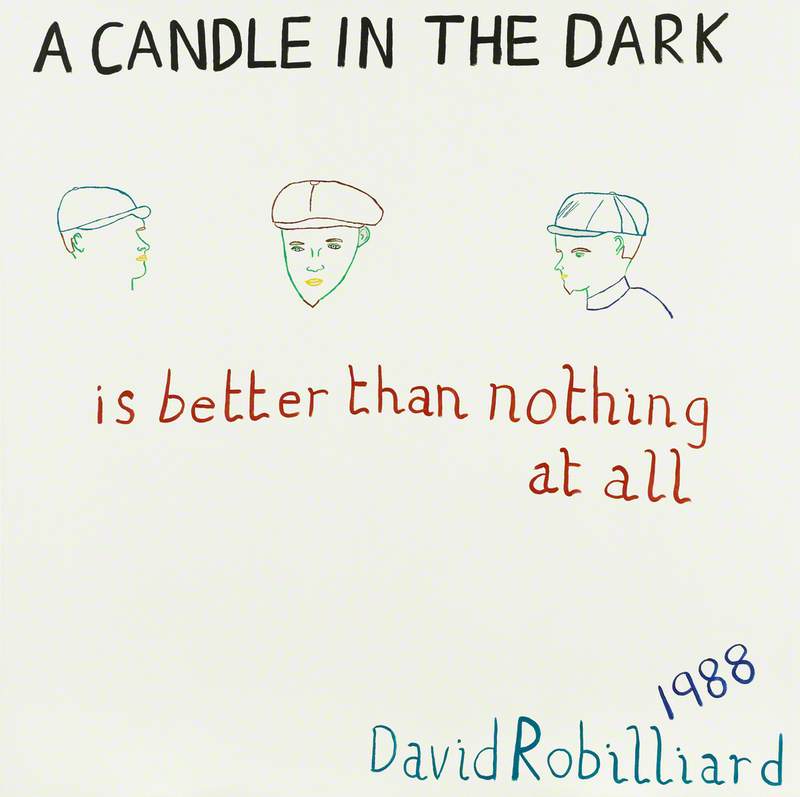

David Robilliard

David Robilliard was a British artist and poet who was mentored by the artistic duo Gilbert & George. An autodidact, known for combining images with written text, Robilliard also published books of poetry in the 1980s.

In a relationship with the artist Andrew Heard from 1983 onwards, both artists were diagnosed as HIV-positive in the late 1980s. Robilliard eventually died of complications from the AIDS virus in 1988, followed by Heard in 1993. Known for his sharp and dark humour (often apparent in his work) Robilliard took to calling himself 'David Robilli-aids' after receiving his diagnosis.

A candle in the dark is better than nothing at all

1988

David Robilliard (1952–1988)

Today, many of Robilliard's works belong to the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Tate Modern and the Arts Council Collection.

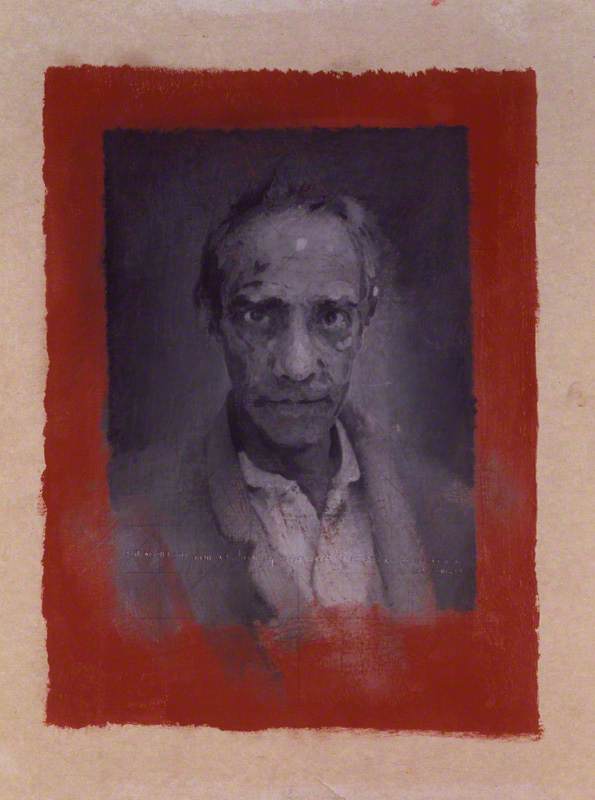

Peter Hujar

An influential artist-activist of the LGBTQ+ liberation movement, Peter Hujar documented the varied experiences of queer life between the 1960s and 1980s. Although he received little acclaim during his life, he has been posthumously recognised as one of the greatest American photographers of the postwar era.

Like Mapplethorpe, Hujar posed for Warhol, whom he met while the artist was screen testing for his short film The Thirteen Most Beautiful Boys (1964–1965). A couple of years later, Hujar would receive training from the renowned photographer Richard Avedon.

Hujar was present at the watershed historical moment of the Stonewall riots in 1969, alongside his lover, Jim Fouratt, a leading gay rights activist.

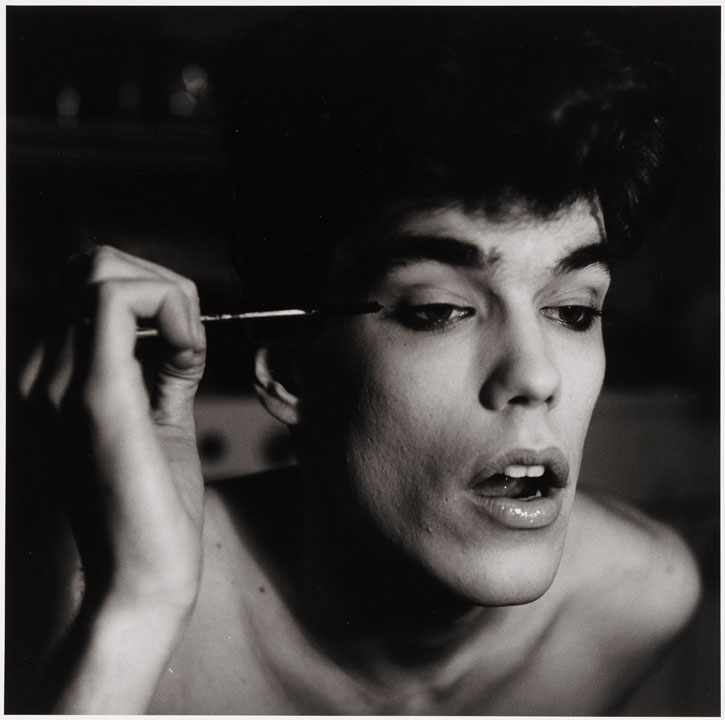

David Brintzenhofe Applying Makeup (II)

1982, photograph by Peter Hujar (1934–1987)

Later in his career, Hujar met and became the lover of the younger artist David Wojnarowicz, who eventually became a household artist embodying 1980s queer culture. Influenced by Hujar, who died of an AIDS-related illness in 1987, Wojnarowicz became a prominent gay rights and AIDS activist in the 1980s. His well-loved books, such as Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration (1991), recounted the experiences of living as a gay man in an era of entrenched homophobia, his time spent homeless, and the pervasive alienation of New York City. Like Hujar, he passed away from AIDS-related complications in 1992.

Derek Jarman

The filmmaker and artist Derek Jarman found his voice as a gay rights activist during the AIDS crisis in the 1980s. Open about his sexuality and living with advanced HIV, Jarman often created films and work that highlighted the discrimination and mistreatment of AIDS sufferers at the hands of the British media. He was also vocal in protesting Margaret Thatcher's Section 28 Local Government Act, which forbade authorities from promoting homosexuality.

Although Jarman passed away in 1994, his legacy was firmly cemented as an icon of British arthouse and queer cinema. His abstract artwork was accompanied by his impressive film oeuvre, including Sebastiane (1997), The Last of England (1987), Caravaggio (1986) and Blue (1993).

Keith Haring

By the time Keith Haring died of complications arising from AIDS at the age of 31 in 1990, he had left behind an enormous oeuvre of work and was a celebrated artist. Known for his stylised, graffiti-like murals that could be seen across New York in the 1980s, Haring used his street and commercial art to confront sociopolitical themes, as well as the silencing of discussions around homosexuality and AIDS.

Like Warhol, he is credited for creating his idiosyncratic artistic trademark, which allowed his comic-like style to become an ubiquitous brand seen not only in public spaces, but on clothing and other products of mass advertising. His work was inspired by the creatives of his era, especially his close friends, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Warhol.

View this post on Instagram

Embodying the youthful spirit of a younger generation of artists in New York, Haring regularly attended clubs like the Mudd Club, Club 57 and other nightlife scenes that were the epicentre of the gay scene.

After being diagnosed with AIDS in 1988, Haring used his work to begin campaigning for safer sex and awareness about the illness. In the same year, a group of artists involved with the ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) grassroots movement established Gran Fury, an AIDS activist collective. Haring's famous 1989 poster Ignorance = Fear, Silence = Death had been used to promote the message of ACT UP.

Haring died of AIDS-related complications in 1990. One year before his death, he established the Keith Haring Foundation, which provides funding to AIDS awareness charities and children's programmes.

Although it is over four decades since the AIDS crisis took hold of society, real and open conversations about the lives lost have only recently been raised in mainstream culture. It is important that we continue to discuss the impact of the work of these artists, and their significant contributions towards raising awareness about the virus.

Lydia Figes, Content Creator at Art UK

Further reading

Kirsten Ann Stuhltrager, Queer Culture Collection, English and Women's Studies 245: Introduction to Lesbian and Gay Studies, 2015

Muri Assunçao, 'How AIDS Changed Art Forever', Vice, 2017

Matt Cook, 'Archives of Feeling: the AIDS Crisis in Britain 1987', History Workshop Journal, Vol. 83, Issue 1, 2017, pp.51–78