An obvious achievement of Art UK has been making readily available to everyone for their enjoyment over 200,000 oil paintings in public collections, works often previously inaccessible. Serious researchers have also benefited. Locating work by artist's name, subject or place, for example, that previously took a long time with no assurance that what was found was comprehensive, can now be accomplished in minutes. This research tool will be enhanced as site visitors volunteer information from specialist knowledge.

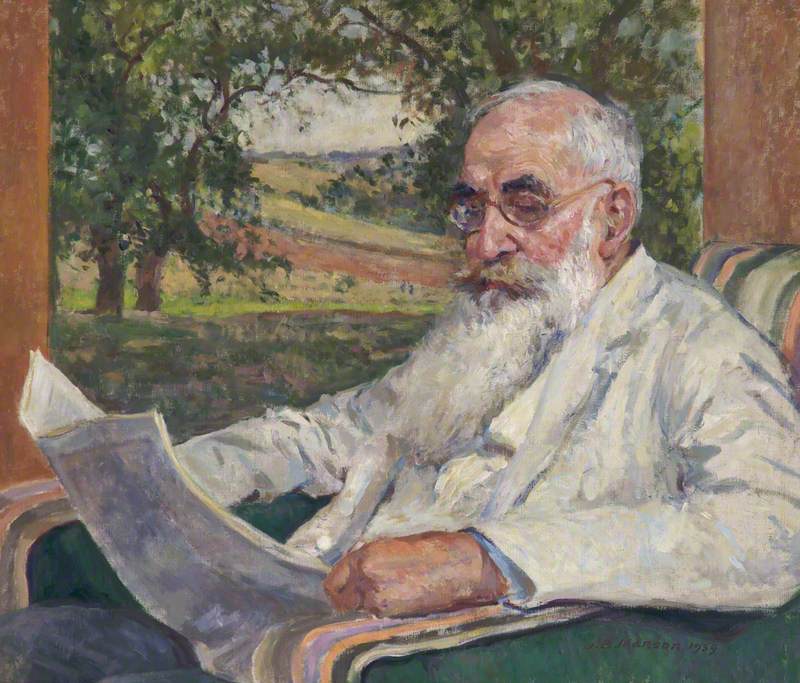

I first encountered the problem of locating pictures in public collections in the 1970s when researching a monograph on James Bolivar Manson. Nothing substantial had been written on this former secretary of the Camden Town Group and director of the Tate Gallery. In the time available, it was impractical to approach every public collection in the country, so tracing pictures depended on press cuttings, Manson's substantial correspondence with the artist Lucien Pissarro, maddeningly unsorted, and family memory. Finally, 34 works in various media were laboriously traced to British and foreign collections, including 24 oils in the former. Now, a minute's research on Art UK adds 11 paintings, making 35 attributed to or associated with the artist.

A comparable task was much greater as I researched my book From Bow to Biennale: Artists of the East London Group, published by Francis Boutle in 2013. The Group's activities had never been chronicled. Thirty-five artists could be classified as members, that is, ones who had shown in Group-associated exhibitions.

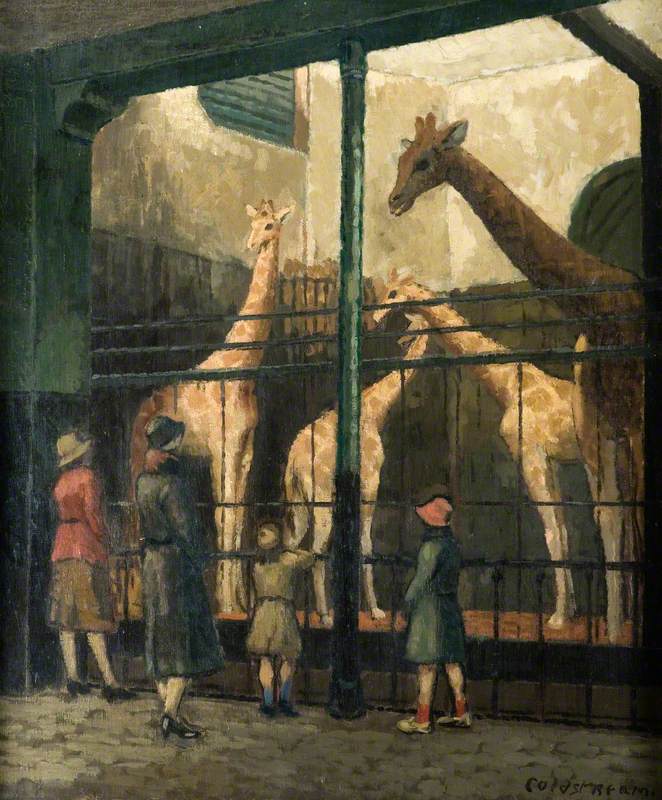

They ranged from notables such as Walter Richard Sickert and William Menzies Coldstream; through core members such as their evening class teacher John Albert Cooper and his wife Phyllis Bray, by whom it was reasonable to expect works to have been acquired publicly; to obscure names such as D. Emerson Chapman, G. M. McCarthy and C. and F. Spelling, about whom little could be traced.

Discounting Sickert and Coldstream, whose publicly held paintings were abundant and well recorded – 279 and 52 respectively, according to Art UK – in the end an amazing 80 paintings by 17 other Group artists were located. This was in addition to works on paper, unrecorded for the purposes of the book. When I had begun to assemble such data I had been dependent on sources like press cuttings, artists' letters and records, catalogues and Contemporary Art Society input, but it was liaison with Art UK that completed my list.

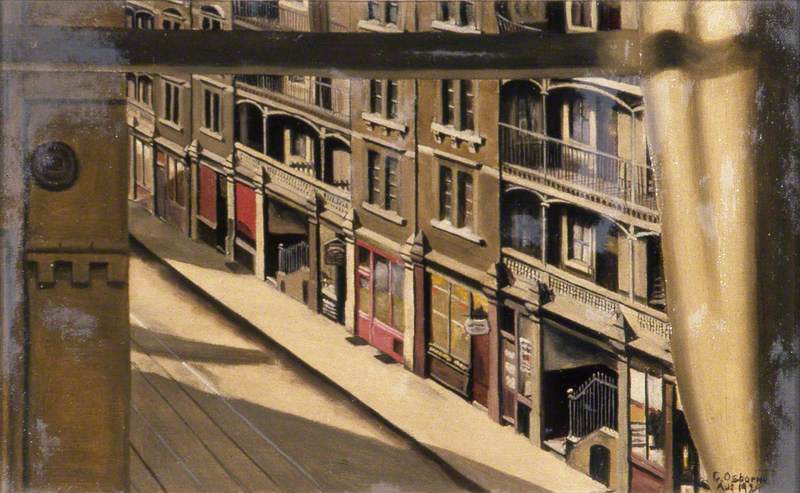

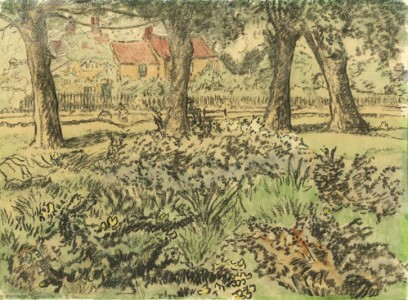

Finding out what each of the 17 artists had in public collections enhanced understanding of their output. At first, many of the East Enders' pictures had focused on the area in which they lived, such as Bow, Bethnal Green and Hackney, their family and friends or still lifes in the home or classroom. This remained true of Albert Edward Turpin, whose mission was to record the East London he had grown up in before it disappeared.

Lakeview Estate, Old Ford Road, from Victoria Park Boating Lake

Albert Edward Turpin (1900–1964)

However, as some artists' circumstances changed and travel became easier, horizons broadened.

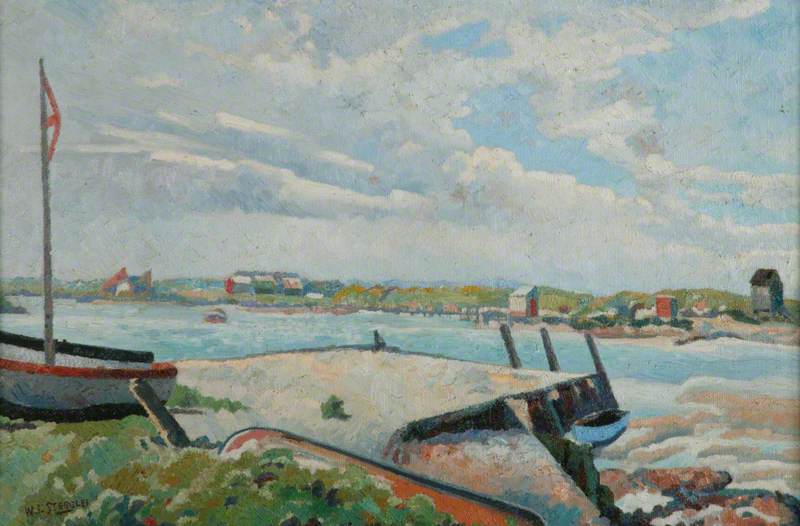

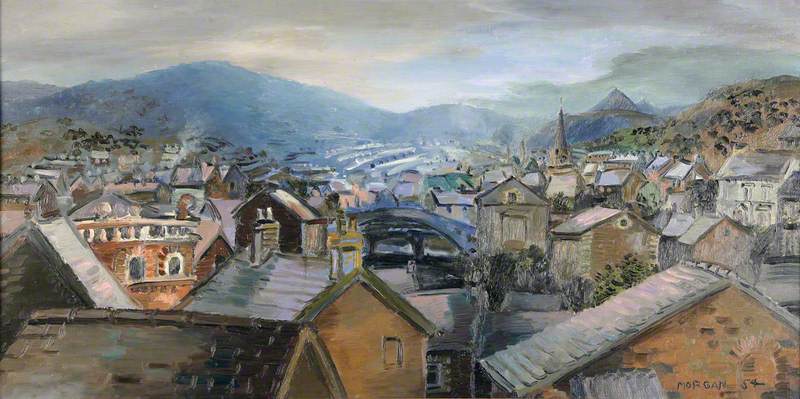

The aspirational Steggles brothers Harold and Walter bought a small car and toured England, painting as they went, an enthusiasm for travel reflected in their publicly held pictures. By the late 1930s they were making trips to the South of France around Nice, St Tropez and Grasse.

When I was asked to proofread some of the Public Catalogue Foundation's early printed volumes, one of the most satisfying aspects was being able, in a few cases, to attribute pictures to artists where, say, misattribution was obvious or only initials provided a clue.

A work labelled as by Patrick Mackintosh proved to be by that fine Scottish landscape painter James McIntosh Patrick. A scene with figures by 'A. E.', infused with a Celtic Twilight atmosphere, could be attributed to the Irish poet and painter George William Russell, who had adopted the initials as his pseudonym.

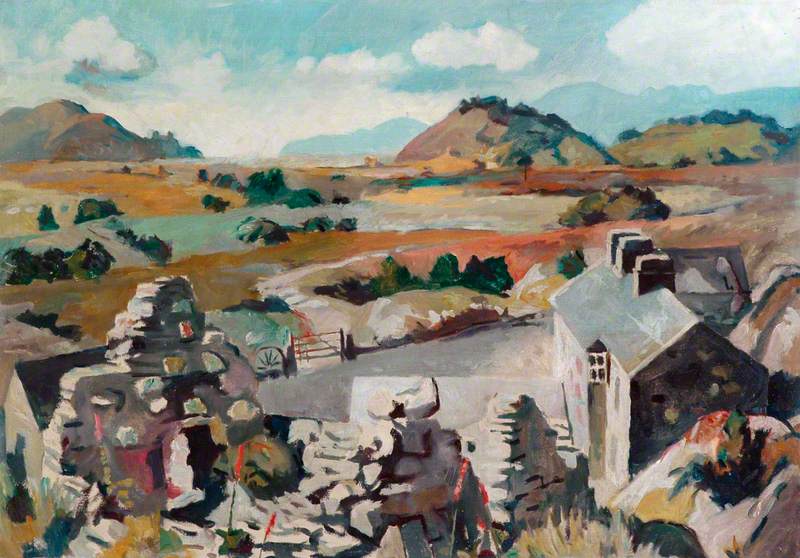

It was the veteran dealer and restorer Winifred Wilson, widow of Sickert's dealer R. E. A. Wilson, who many years ago cautioned me not to trust signatures, as an artist's identity was 'painted all over the picture'. This advice proved true in the cases of the McIntosh Patrick and A. E. pictures and would again when compiling the East London Group list. At the last minute I was alerted to an apparent anomaly among four pictures attributed to one John Hubert Cooper.

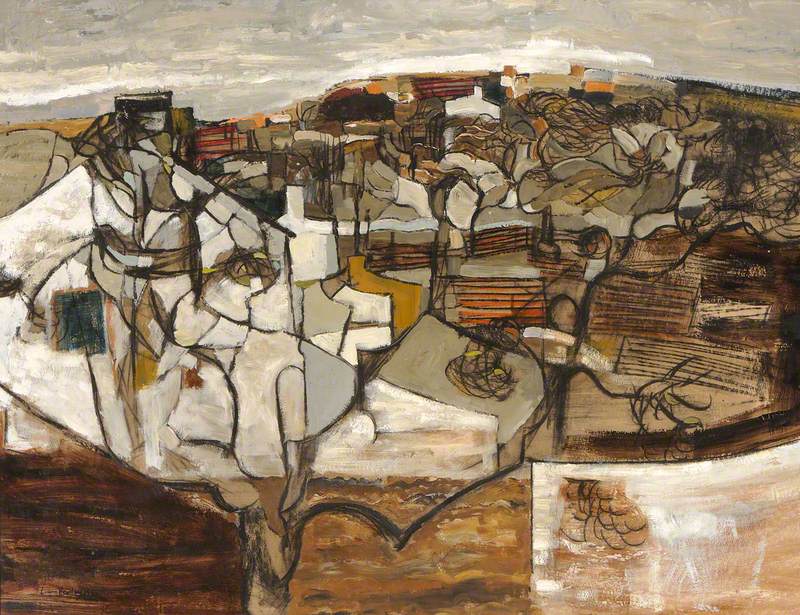

Three were evidently by John Hubert, but Stone Cottages, held by The Hepworth Wakefield, clearly was not. Stylistically this was by the East London Group's founder, John Albert, such rock-strewn landscapes a feature of his output. Now it is rightly placed among the 13 John Albert Coopers that Art UK lists.

David Buckman, art historian