The Monarch of the Glen is one of the most resonant and recognisable British paintings of the nineteenth century.

It was painted in 1851 by Sir Edwin Henry Landseer for the House of Lords, but because of controversies around the cost of new works of art being commissioned by Parliament, it was sold to a collector. The painting remained in private hands until 2017 when it was acquired by the National Galleries of Scotland, but has never been out of the public eye.

Its celebrity status was originally in part due to the reputation of Landseer himself, who, by the 1850s, was Britain's pre-eminent animal painter. Thanks to numerous reproductions of his works, especially via steel engravings, he was also one of the most famous artists in the world.

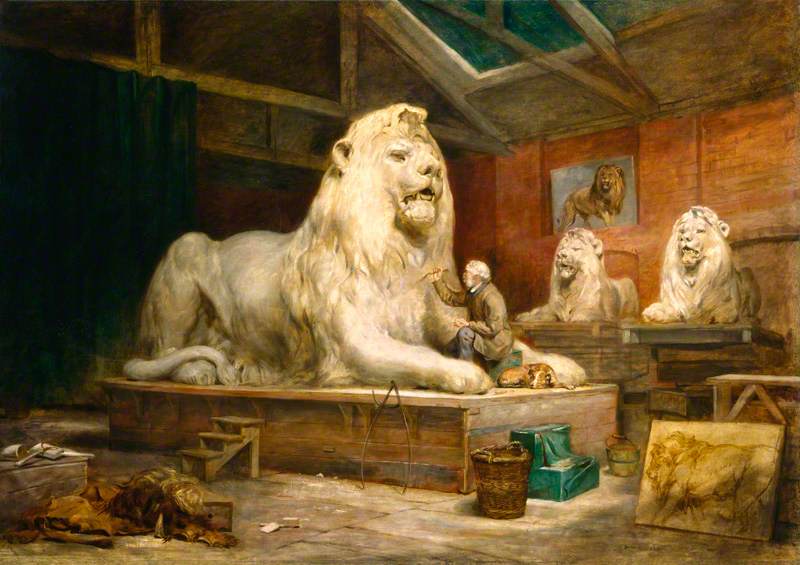

Landseer's Monarch was first exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts, which at the time was housed within The National Gallery. During the following decade, he designed the other most public and affectionately regarded commission of his career – the bronze lions at the base of Nelson's Column, which dominate Trafalgar Square in front of the Gallery. They have become a symbol of 'Britishness', while the Monarch remains above all a Scottish icon.

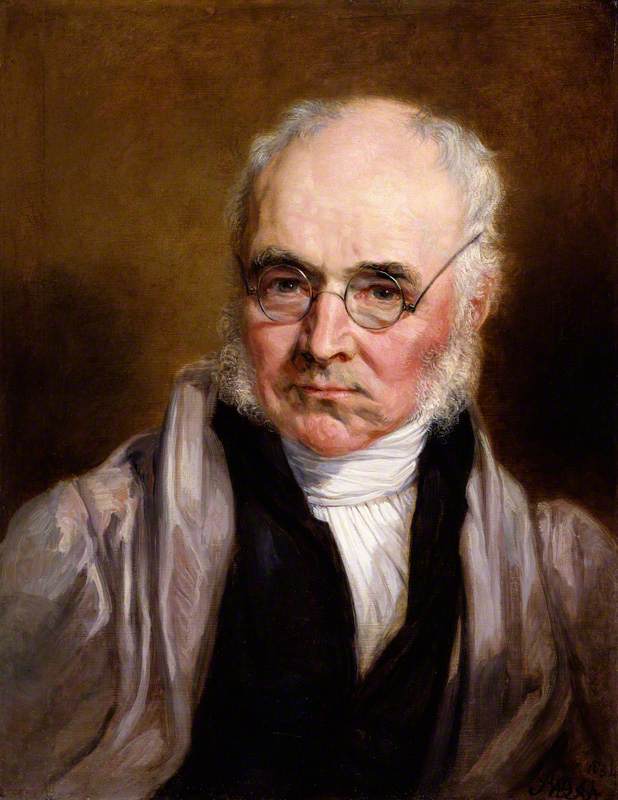

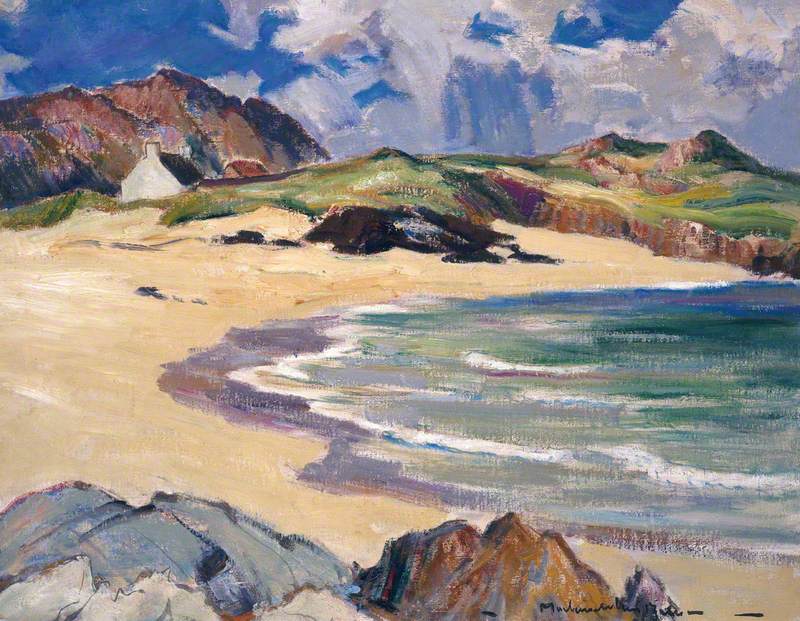

Landseer was born in London in 1802 and first visited Scotland in 1824, being overwhelmed by the experience of the landscape and the people. He developed a particular affinity with Sir Walter Scott.

He saw the country as a land of beauty with a riveting history, and some of his most successful sporting pictures and historical works have a highland setting.

The Pot of Gartness, Drymen, Stirlingshire

c.1830

Edwin Henry Landseer (1802–1873)

Although painted in Landseer's studio they were informed by brilliant drawings and oil sketches made on his travels.

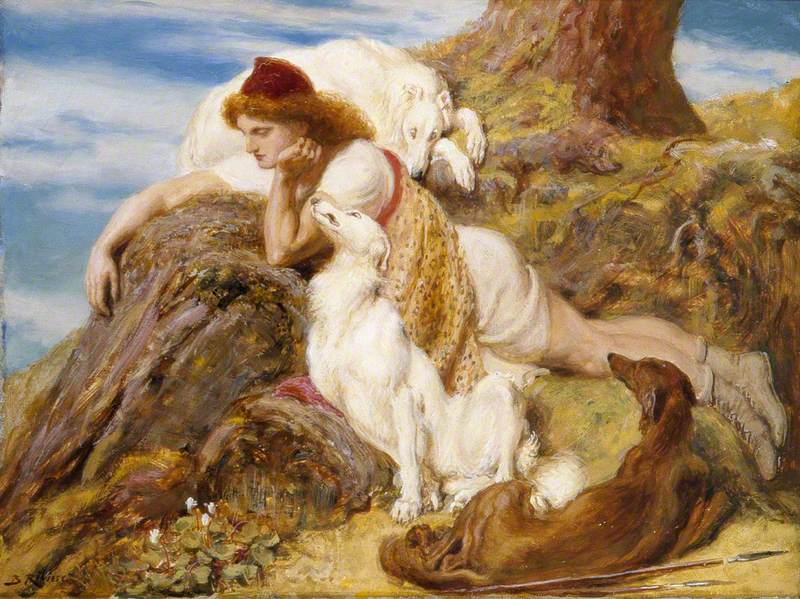

Head of 'Driver', a Deerhound Owned by the 5th Duke of Gordon

Edwin Henry Landseer (1802–1873)

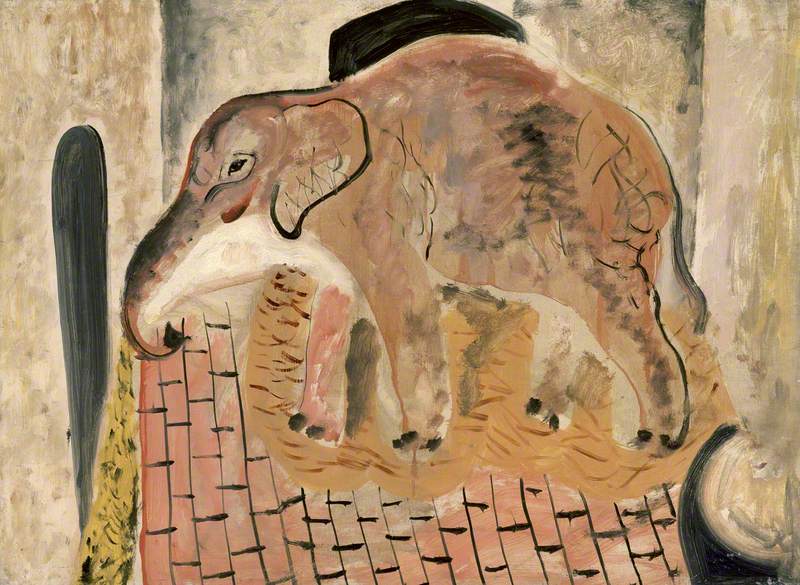

From the 1830s, the artist frequently painted deer and stags. However, he often portrayed them being pursued and at the mercy of hunters or as trophies of the chase.

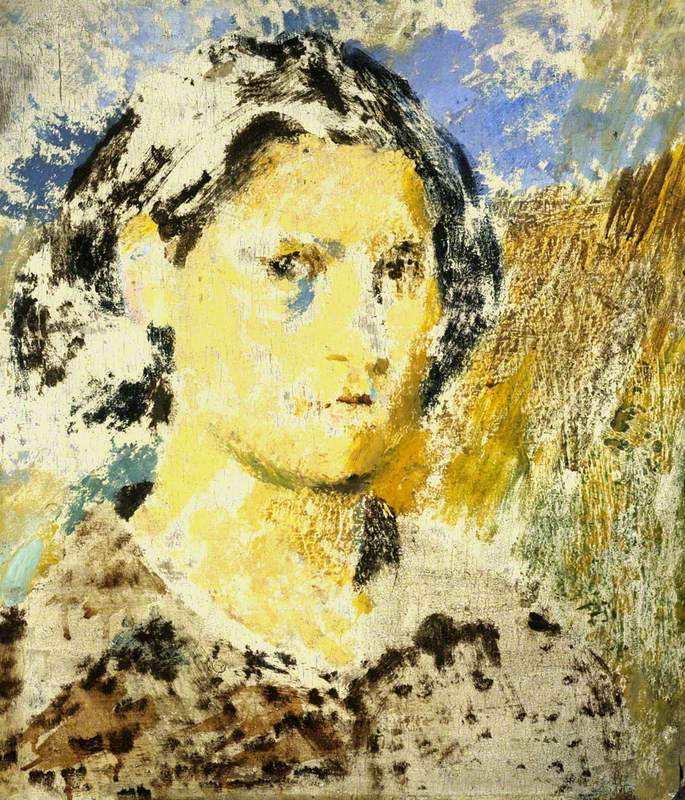

Queen Victoria in Windsor Home Park

1865

Edwin Henry Landseer (1802–1873)

What distinguishes his painting of the Monarch is its dominant, almost triumphal air – the stag appears to be master of all he surveys and unthreatened by any human interaction. He may though have just sensed our presence as a stalker, who has managed, unseen, to get very close to our quarry.

The stag's appearance is precisely defined, with details such as the moisture around his nostrils and even his eyelashes being deftly painted. He is a 'royal' or twelve-point stag – a reference to the number of tines on his antlers. The veracity of his depiction was based on careful studies made in Scotland and London, and on a number of landed estates across England where Landseer was a guest.

The ideal of a magnificent specimen that dominates the kingdom of nature is a compelling one that was also explored by other artists in the nineteenth century, such as Charles Towne and John Linnell.

The Fallen Monarch of the Forest

1850–1880

John Linnell (1792–1882)

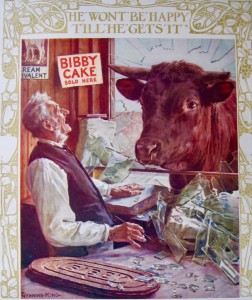

However, while their monarchs – a prize bull and an ancient tree – have been long forgotten, the familiarity of Landseer's creation has endured. This is chiefly because his painting was employed as a hugely successful marketing icon.

The key moment in terms of its shift in status came when the painting was owned by James Barratt (1841–1914), a manufacturer and pioneer of the advertising industry. He inspired Thomas Dewar (1864–1930), 1st Baron Dewar, who bought Landseer's Monarch in 1916, to harness it to promote an archetypal Scottish product – whisky.

In the wake of this, it was endlessly reproduced on packaging. Shortbread and soup are perhaps the most famous examples, but there seems to be no end to its recycling. This all kept the painting remarkably visible through the twentieth century, when conversely the reputation of mid-Victorian art was in a steady decline.

Artistic responses to the Monarch have played cleverly on its dual status as a Victorian paragon in a later age of disrespect. Artists who have been irresistibly drawn to it include Sir Bernard Partridge, Ronald Searle, Sir Peter Blake and more recently Peter Saville.

Although it has perhaps not been universally loved, Landseer's most famous work seems to have lost none of its quality of recognition and ability to inspire.

Christopher Baker, Director of European and Scottish Art and Portraiture at the National Galleries of Scotland