Richard Wilson was born on 1st August 1713 or 1714 in Penegoes, Powys, North Wales, the third son of its rector. Classically educated at home, he grew up to become the leading British landscapist of his generation and one of the great artistic pioneers of the eighteenth century.

More than a decade older than his better-known contemporary, Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788), Wilson was highly popular for a time in his own day – not least because he made of landscape something more than the topographical or descriptive, endowing it with classical and historical associations, emphasising its versatility and raising its status as a genre of painting. He transformed mere views into vehicles of emotion and imagination, laying the foundations on which the great Romantic landscapists John Constable and J. M. W. Turner built their reputations, as well as John Robert Cozens, Thomas Girtin and a host of watercolourists.

In 1729 Wilson left Wales for London, to study painting with a minor portraitist, Thomas Wright. He later attended the St Martin's Lane Academy, set up by William Hogarth.

By 1735 he had left Wright's studio and established himself as a proficient and moderately successful artist, capable of producing such memorable portraits as those of Commodore Thomas Smith and Flora MacDonald.

Flora Macdonald (1722–1790), Jacobite Heroine

1747

Richard Wilson (1713/1714–1782)

In the mid-1740s, perhaps prompted by the example of George Lambert, he produced a few landscapes, including Dover Castle.

This side of his talent gained wider publicity through two roundel views, The Foundling Hospital and St George's Hospital, that he presented to the newly-built Foundling Hospital, one of the first public exhibition spaces in London.

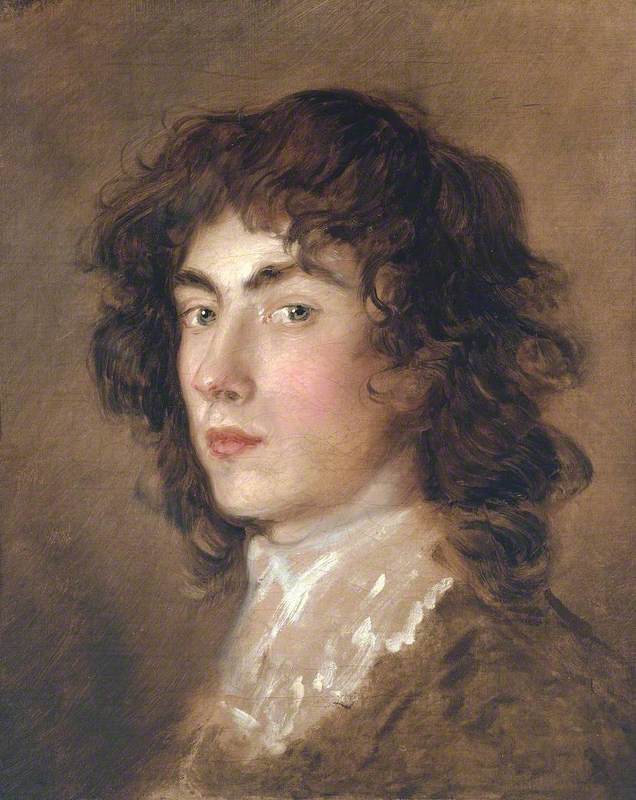

In his late 30s, Wilson decided to travel to Italy, where he finally abandoned portraiture. In 1751 in Venice he was encouraged to change course by the successful landscape painter Francesco Zuccarelli (1702–1788), and soon afterwards was befriended in Rome by the internationally renowned French landscapist Claude-Joseph Vernet (1714–1789), who strongly advocated landscape in preference to portraiture.

Two of the principal Roman landscapists, Andrea Locatelli and Jan Frans van Bloemen, known as l'Orizzonte, had recently died, whereas the portrait market was dominated by Pompeo Batoni and Anton Raphael Mengs. Another incentive was a constant demand for souvenirs of Italy from the young Grand Tourists, who came to finish their education there.

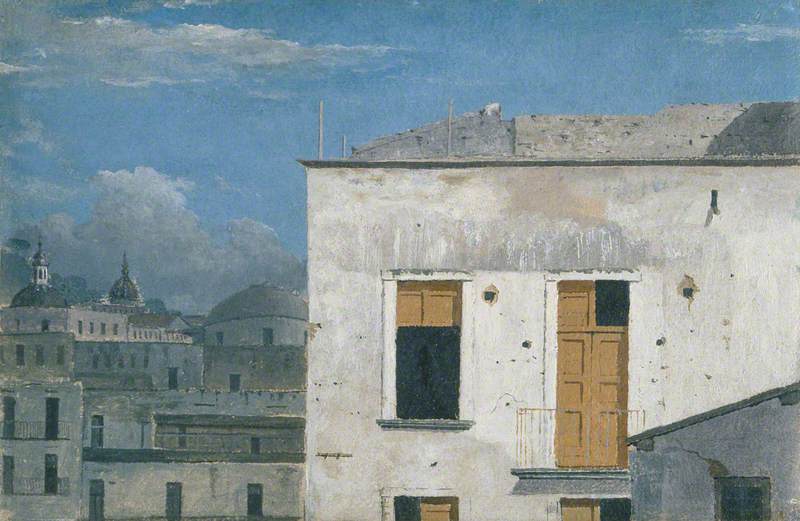

Over the five years or so that he spent in Rome, Wilson executed many views of the city and the surrounding Campagna, and of Naples with the adjacent area. He also ran a successful studio with international pupils.

His Italian landscapes were overlaid with innovative and imaginative use of light and atmosphere which endowed them with a mood of ineffable poetry. Works like View of Tivoli: The Cascatelle and the 'Villa of Maecenas' enjoyed great popularity with Grand Tourists returning from what they took to be a lost Utopia. As signifiers of bygone power, they were guaranteed to appeal to the classically educated future rulers and legislators of Britain, and presented a poignant comparison between ancient Roman grandeur and the decayed condition of modern Italy.

View of Tivoli: The Cascatelle and the 'Villa of Maecenas'

c.1752

Richard Wilson (1713/1714–1782)

On his return to London in 1757 Wilson established his residence and studio in the fashionable Covent Garden Piazza. There he continued to execute masterly reminiscences of Italy, such as Classical Landscape, which were in high demand and frequently repeated by the artist and his pupils.

Landscapes in the manner of the Old Masters he most admired – Claude Lorrain, Gaspard Dughet and Salvator Rosa – became settings for narratives taken from ancient mythology, in which he sought to put landscape on an equal footing with the academically prestigious genre of history painting. These reached an apogee with The Destruction of the Children of Niobe, exhibited at the Incorporated Society of Artists in 1760.

The Destruction of the Children of Niobe

1760

Richard Wilson (1713/1714–1782)

It was bought by the Duke of Cumberland, uncle of George III, and became the pivotal composition of Wilson's career, paving the way for his nomination as a Founding Member of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1768.

Wilson also painted more traditional 'estate portraits' of country seats, such as Wilton House, Wiltshire, and popular settings, such as The Thames at Twickenham; but even these struck a new note by playing down the houses featured while emphasising the landscape and its atmosphere.

Wilton House from the Southeast

1758–1760

Richard Wilson (1713/1714–1782)

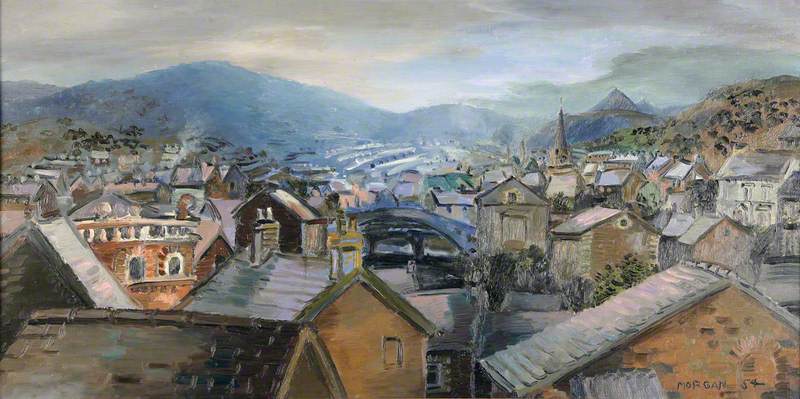

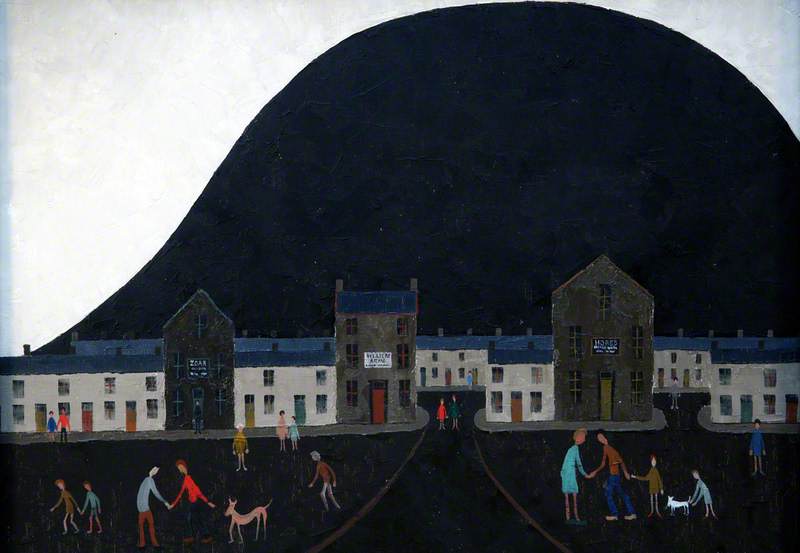

Wilson's own country produced some of his most poetic icons such as Snowdon from Llyn Nantlle, which were often bought by local gentry, some of whom were related to him. These subjects reached a climax in 1771 with the completion of Dinas Bran from Llangollen and View near Wynnstay for the landowner, Sir Watkin Williams-Wynn.

View near Wynnstay, the Seat of Sir Watkin Williams-Wynn, 4th Bt

1770–1771

Richard Wilson (1713/1714–1782)

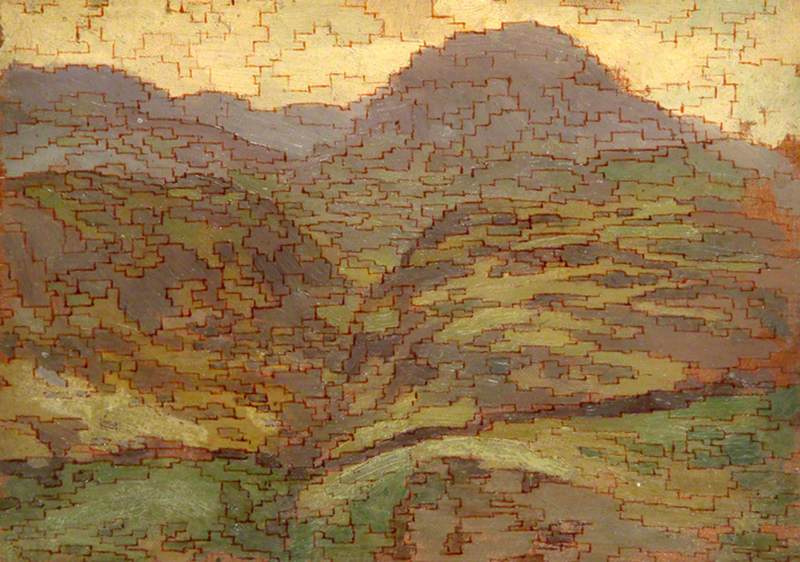

In these magnificent compositions, the artist skillfully combined particularities of topography with subtle lighting and bucolic figures, imbuing his native landscape with an Italianate serenity, and transforming the North Welsh countryside into a veritable Arcadia. The appeal of such landscapes was much enhanced by a rising public interest in Welsh history and customs from the 1750s. This and a new fashion for wild or 'sublime' subjects also spurred Wilson on to his most conceptually innovative picture Llyn-y-Cau, Cader Idris whose uncompromising starkness meant that it remained unsold.

In later years Wilson's reputation underwent a rapid decline, from which it recovered only some decades after his death in 1782 – and from which, to a degree, it continues to suffer. Unmarried, struck by ill health, becoming ever more irascible, opinionated and anti-social, and turning increasingly to drink, he was temporarily rescued from poverty by his fellow Academicians, who in 1776 appointed him to the post of Librarian at an annual salary of £50. However, he was unable to continue beyond 1781 and retired to the home of his cousin Catherine Jones at Colomendy Hall, Clwyd, where he died on 11th May 1782.

Despite the popularity of engravings after his paintings and the many later copies and pastiches of his work made in the nineteenth century, he himself had become an obscure figure whose uneven reputation was succinctly captured by a critic, 'Peter Pindar', in Lyric Odes to the Academicians that same year:

But honest Wilson, never mind;

Immortal praises thou shalt find,

And for a dinner have no cause to fear.

Thou start'st at my prophetic rhymes:

Don't be impatient for those times;

Wait till thou hast been dead a hundred year.

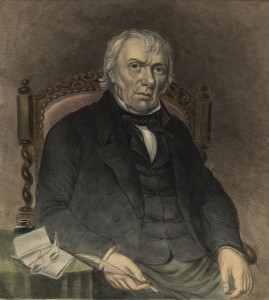

Richard Wilson (1714–1787)

1752

Anton Raphael Mengs (1728–1779)

In 2014 a major exhibition, 'Richard Wilson and the Transformation of European Landscape Painting', was held at the National Museum Wales, Cardiff and Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, USA to celebrate the 300th anniversary of Wilson's birth and re-establish his position as an artist of international stature.

Simultaneously, Richard Wilson Online, a digital catalogue raisonné of his work was published by the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. This seeks to re-assess Wilson's reputation by clarifying and redefining his entire output. It updates and combines the classic catalogues of his paintings by Professor W. G. Constable (1953) and drawings by Sir Brinsley Ford (1951) and incorporates new insights highlighted by the landmark exhibition 'Richard Wilson: The Landscape of Reaction' (1982–1983) curated by Professor David Solkin. Richard Wilson Online provides an up-to-date and freely accessible reference tool for a modern audience, reinforcing the Welshman's status as the father of British landscape painting.

Paul Spencer-Longhurst, former Senior Research Fellow at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, and Editor of the digital catalogue raisonné of the work of Richard Wilson