In the STORIEL collection of Gwynedd Museum and Art Gallery in Bangor, there is a wooden figure, around two feet tall, made by a Flemish carver around the year 1520. It represents Saint Wilgefortis, and the story behind this sixteenth-century object encompasses bearded women, oppressed people and gender fluidity within religious iconography. Interpretations of Wilgefortis's legend disrupt the binaries of male and female, and the human and the divine.

Taking a close look at the figure, the face has a high forehead, with arched eyebrows and downcast eyes that suggest a humble or contemplative expression. The person has long, curling hair and a short, neat beard.

Saint Wilgefortis

(detail), c.1520, wood by unknown artist

It seems that the clothing on this figure is particularly feminine: there are beads on a necklace, ruched folds of the undershirt at the neck, and a cinched waist with a floral motif in the middle. Seen from the side, the figure seems to have a bust. The feet are covered by a shroud tied loosely at the ankles. The folds of fabric and waves of hair suggest softness.

Saint Wilgefortis

(details), c.1520, wood by unknown artist

No arms are visible, and a cloak covers the shoulders. The angle of the shoulders, raised up, suggests the arms may have been splayed out, like on a crucifix – perhaps they were broken off, as the rectangular holes at the sides attest.

How did a Flemish object come to be in Wales? The collection website explains the item was originally owned by Captain John Jones, a master mariner who collected objects on his travels and set up his own museum in Bangor. In Europe, after the Protestant Reformation in the sixteenth century, many churches were stripped of decoration and these works of art were destroyed or even looted and sold, as part of the Beeldenstorm ('image storm').

This Flemish image of Saint Wilgefortis, usually venerated by Catholics, clearly didn't escape the looting. Also known as 'The Bearded Lady', Wilgefortis is known for her facial hair. The legend goes: the young Christian Wilgefortis was the daughter of the pagan King of Portugal, who arranged for her to be married to a suitor. The young woman, who had taken a vow of chastity, prayed to be made repulsive and released from the betrothal. Her prayers were answered in the form of a luscious beard. The new facial adornment put off the potential husband, and Wilgefortis's father was so angry that he had her crucified.

Her story made her a popular saint with women who were in unhappy, abusive situations. The variations of her name across Europe echo parts of her tale: Saint Uncumber ('disencumbered'), Saint Ontkommer or Kümmernis ('ohne Kummer', without anxiety), Saint Liberata or Librada ('liberated'). Wilgefortis sounds also like virgo fortis ('courageous virgin' in Latin).

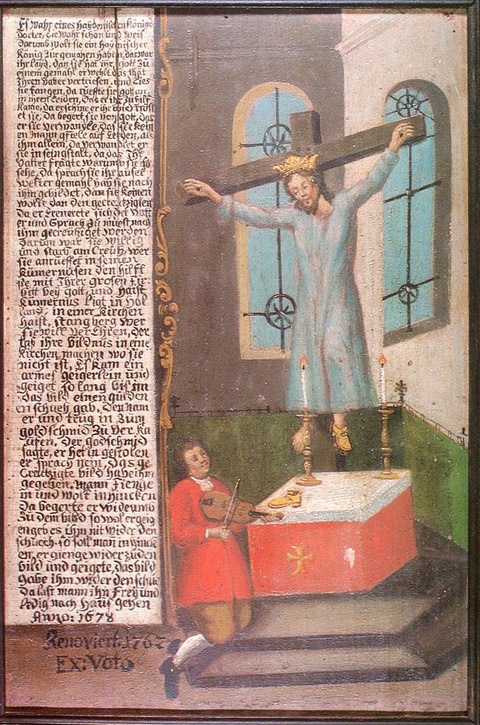

Saint Kümmernis

1678, painting by unknown artist

Images of Wilgefortis use her beard as a visual clue – as well as a missing or fallen boot, or a golden boot: versions of the tale include a young fiddler, who played for Wilgefortis during her crucifixion. She rewarded him by giving him one of her golden boots, and then the other boot after he was accused of stealing the first. In some depictions, her beard is barely there – such as in Hieronymus Bosch's triptych (once thought to be Saint Julia, but conservation work revealed the figure to be bearded).

The Crucifixion of Saint Wilgefortis

(detail), c.1497, oil on panel by Hieronymus Bosch (c.1450–1516)

In other artworks, Wilgefortis's beard appears full and flowing.

Saint Liberata (Uncumber, Wilgefortis)

coloured etching by unknown artist

While the saint was popular during the sixteenth century, Wilgefortis's legend was debunked, though her image occasionally appears in art from later centuries – even as a statue in Westminster Abbey.

Legend has it that St Wilgefortis prayed for God to make her hideous to her future husband. Miraculously, when she awoke the next morning she discovered she'd grown a beard! The beard had the effect Wilgefortis had hoped for and the wedding was called off. #PeculiarPeopleDay pic.twitter.com/3nFDNIfeXT

— Westminster Abbey (@wabbey) January 10, 2019

But if Wilgefortis was never real, what started the legend?

Hippolyte Delehaye, a Jesuit scholar, proposed in 1906 that the cult of Wilgefortis was actually started because people thought a popular image of Jesus Christ showed a crucified woman. It seems strange that the most well-known figure in the Christian religion could have their identity mistaken, but Delehaye believed it all started with an object in the city of Lucca, Italy – the Volto Santo, or Holy Face.

E' originale il crocefisso del volto santo di Lucca, venerato fin dal medioevo. Ora c'è la conferma scientifica. Risale all'VIII secolo ed è la più antica statua lignea dell'occidente

— Tg2 (@tg2rai) June 20, 2020

Al #Tg2Rai delle 13.00 del #20giugno pic.twitter.com/xvVC3tGJq0

The carving of Jesus Christ is the oldest known wooden sculpture in Europe, radiocarbon dated to AD 770–880, but lots of other later copies exist. It's thought that the long robe worn by the Holy Face caused people in the Low Countries to see a (bearded) figure in a dress. The name Wilgefortis could even be a corruption of 'Hilge Vartz', or 'holy face'.

The Museum of London have a medieval pilgrim badge of Jesus mistaken for Saint Wilgefortis, and it's imagined that many such examples still confuse curators today.

The Catholic Church downgraded the saintly status of nearly 100 figures (in a revision of 1969) due to their uncertain histories, including that of Wilgefortis – her feast day on 20th July is no longer officially celebrated. However, Saint Wilgefortis remains an inspirational and intriguing story, particularly resonating with women and LGBTQ+ people.

Looking at her story through a queer lens, contemporary viewers may adopt the icon as a symbol of gender fluidity: while Wilgefortis's identity is not that of a trans or queer person, she subverts gendered societal expectations. Her legend disrupts ideas of binary gender, as does the interpretation of a gender-ambiguous Jesus Christ. In the New Testament, Paul says: 'There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.' (Galatians 2:28) – with this statement, Jesus blurs the division between the human and the divine, and even boundaries of race and gender.

Wilgefortis as a chaste virgin, refusing gendered expectations, weaponising her appearance, hints at the archaic trope of the 'lesbian virgin' – women who reject heteronormative, patriarchal values and choose their own path.

Wilgefortis as a bearded woman has also led to her interpretation as a patron saint of intersex people, transgender people or those with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. In cultural history, we have glimpses of women with hirsutism (excessive facial hair growth) who inspire new thinking on gender, such as Phaethousa of Abdera, who stopped menstruating and grew a beard after her husband left.

Hirsute women challenge gendered expectations and limitations. As people, they are unconventional and often even exploited, yet their beards enable power or independence: Macbeth's powerful witches were bearded, and numerous real 'Bearded Ladies' of nineteenth-century circuses were independent entertainers, supplementing their income through their facial hair.

Barbara van Beck (b.1629)

c.1650

Giovanni Francesco Guerrieri, Italian (Lombard) School

Women as early as the sixteenth and seventeenth century made a living from their hirsutism, such as Barbara van Beck, and likely an Italian woman named Magdalena Ventura, painted in 1631 by Jusepe de Ribera.

Magdalena Ventura with Her Husband and Son

1631, oil on canvas by Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652)

Other saints can be viewed through a queer lens, or their stories hint at queer histories: such as Saint Sebastian (as a gay icon), Joan of Arc, charged with heresy and cross-dressing, or Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, who apparently had a passionate, long-term relationship with the archbishop Malachy. Ultimately the images of Saint Wilgefortis make for intriguing jumping-off points for contemporary viewers to consider gender stereotypes, expectations and limitations.

Jade King, Lead Editor at Art UK

.jpg)