Why do we not know the name Samuel Fyzee-Rahamin?

This name is not in the public consciousness of Britain. It is neither well-known among the curators, historians, experts who contribute to the canonisation processes of art and determine what is important to Britain's cultural memory.

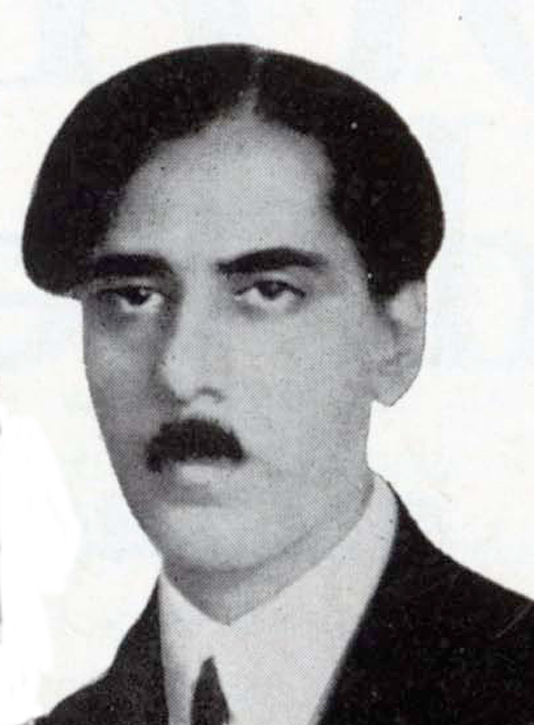

Samuel Fyzee-Rahamin

c.1912, photograph by an unknown artist

I have grown used to seeing the unfamiliar look on the face of the expert when uttering the name Samuel Fyzee-Rahamin. At best, there is a fleeting familiarity to this name, as an early 'Indian' artist whose work may have been drawn into various thematic exhibitions – on landscapes, or on empire. A referential artist, to think of within the context of recent exhibitions or broad trends rather than a specific legacy.

Yet, this very artist has a monumental place in British art history. Samuel Fyzee-Rahamin is likely the first Muslim artist to enter the collection of the Tate Gallery, and perhaps even the first non-European artist to enter this collection too. The Tate is a collection that is described as holding 'the national collection of British art from 1500 to the present day', symbolising what is relevant and required to represent British art history. This should not be something that is unfamiliar. Beyond this case for representative recognition, it also highlights the crushing of histories and the loss of sculpting a present and future of Britain that is reflective of ever-expanding experiences.

The fact that this artist's presence in the UK is largely locked in the stores and archives of institutions, in scattered fragments, is shameful. In researching and following the footsteps of Samuel Fyzee-Rahamin in Britain, a century later, I feel an honour in connecting with this artistic presence, but am equally hit by sadness and anger as to how this presence has been treated by the very public art experts who have been keepers of this history.

Born on 19th December 1880, in Poona, Samuel Rahamin's family were part of the Bene Israel, a cultivated Jewish community that had had a presence in India for centuries. Rahamin's first note as an artist starts in his enrolment in the Sir J. J. School of Art, in Mumbai (then known as Bombay).

आजकालची कला - महाराष्ट्र

— MarathiMati.com (@marathimati) July 13, 2019

सर जे. जे. स्कूल ऑफ आर्ट (@jjschoolofart) प्रथम बांधण्यात आले तेव्हाची इमारत १८७८https://t.co/2dborYCknH#मराठीमाती #marathimati

The art school was then administered by the 'Government of India', with a long history of noted European administrators in charge, including Lockwood Kipling (father of Rudyard). Following from this initial art education, in his early 20s, Rahamin found himself with a scholarship opportunity to move to London and enrolled at the Royal Academy. There he was trained in producing academic European paintings, using oil and canvas, and he was taught by canonised stalwarts John Singer Sargent and Solomon J. Solomon.

This journey of Indian artists being indoctrinated into the academic creed of European art – dictating what skills, materials and demeanour a painter should take – was present across many 'Government Art Schools' that emerged in nineteenth-century India. However, it was a move against this formative training which saw a series of artists emerge who defined their practice through a rejection of their academic training. They reorientated their practice into something that could be defined as distinctly 'Indian' – or as some have attempted to describe as the formation of 'Indian Modernism'.

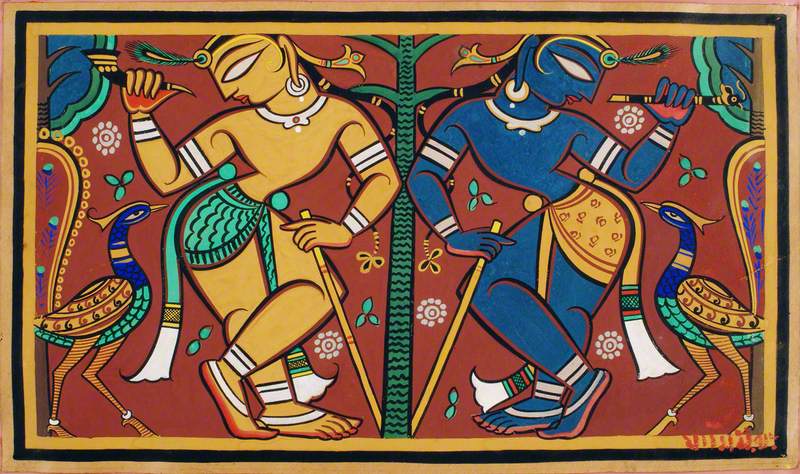

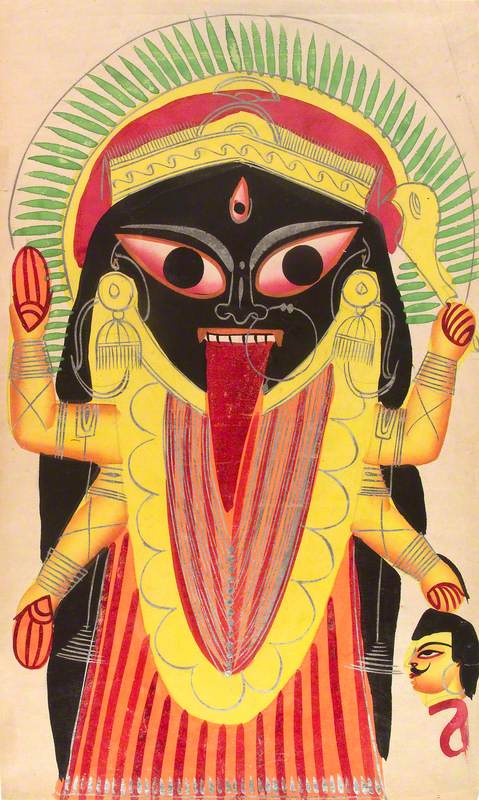

Samuel Rahamin shared this same reorientation from formal academic training with other artists of this generation – for instance, Jamini Roy.

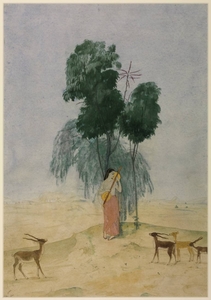

Both artists, after completing their training in European oil painting, had a cathartic reinvention and never touched the medium again. Instead they invoked mediums and approaches that tied them to the historic roots of Hindustan. Jamini Roy began to work in the style of Kalighat painting and Samuel Fyzee-Rahamin moved towards invocations of the Rajput paintings, the Mughal miniatures inspired by local and religious allegorical paintings emerging in the seventeenth century.

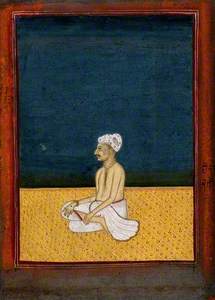

This reorientation of his practice took place after his return to India from his studies at the Royal Academy in 1908, when he took up a position first as a portrait painter, then as an official arts and cultural advisor to the Maharaja of Baroda.

A retrospective reflection on leaving the eminent artistic community in London to return to India, he claimed staying 'would be like the Bengal tiger hunting for seal in the polar regions'. Adapting his European academic training to the services of the Maharaja brought him in close contact with the elite of Indian society. It is a connection through these networks that pushed him to a path that defined his practice, his self – a connection of profound love and divine creativity.

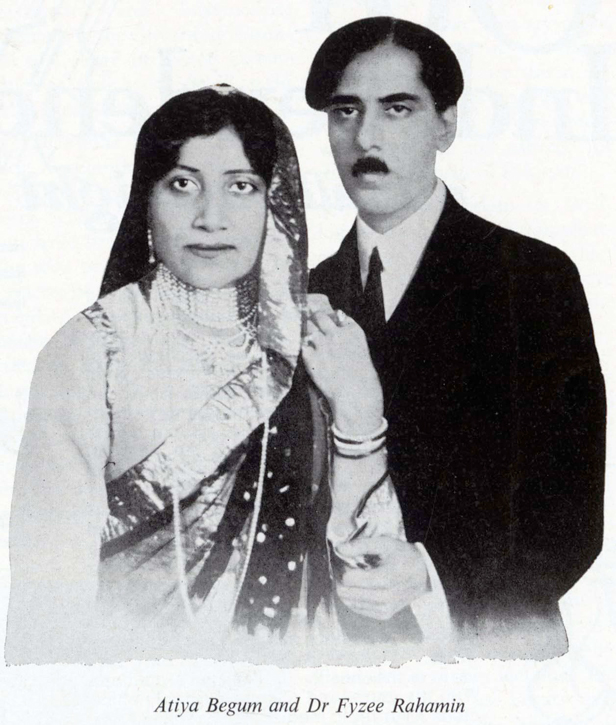

One of the portraits that Rahamin was asked to undertake was that of Ahmed Khan, the Nawab of Janjira (1879–1922). In circumstance of connectivity, in 1912, Samuel Rahamin was to marry Atiya Fyzee, the Nawab's sister-in-law. It was a marriage that was against many traditions of the time, symbolised by both taking each other's surnames, each becoming Fyzee-Rahamin. Samuel also converted to Islam.

The wedding of Atiya and Samuel Fyzee-Rahamin

c.1912, photograph by an unknown artist

This union was the start of a creative partnership powered by love, continuously revolving around critical reflection on interconnected themes – they balanced the pros and cons of a Western-centred modernity with those of their own deep traditions of religion, culture and belief.

Atiya Begum ('Begum' is a royal and aristocratic title in Central and South Asia) is truly a remarkable figure in the poetic imprint of Europe and India/Pakistan.

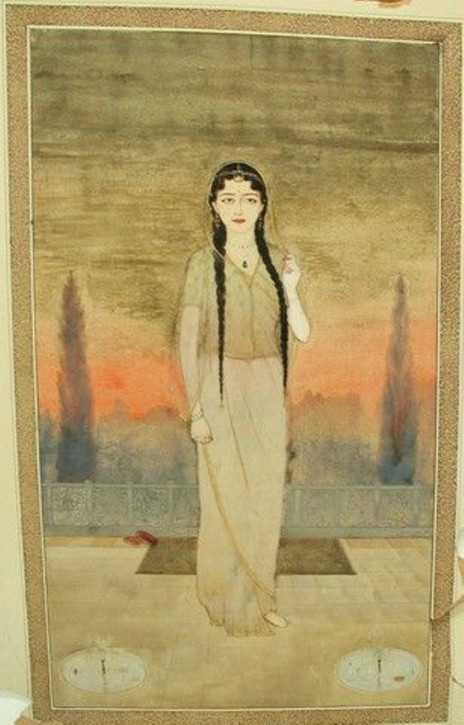

Atiya Fyzee-Rahamin

1921, photograph by an unknown artist from Basanta Koomar Roy's 'Picturesque India' in 'The Mentor' 9

She was the first South Asian woman to attend Cambridge University and she represents the experience of the elite cross-fertilisation of British institutionalism that produced the Oxbridge-educated forefathers of independence – the likes of Jinnah, Gandhi and Nehru. Yet, perhaps as a woman within the masculinity of history, the knowledge of her presence and nuance of her navigation is often also overlooked in its significance.

Atiya Fyzee (1877–1967)

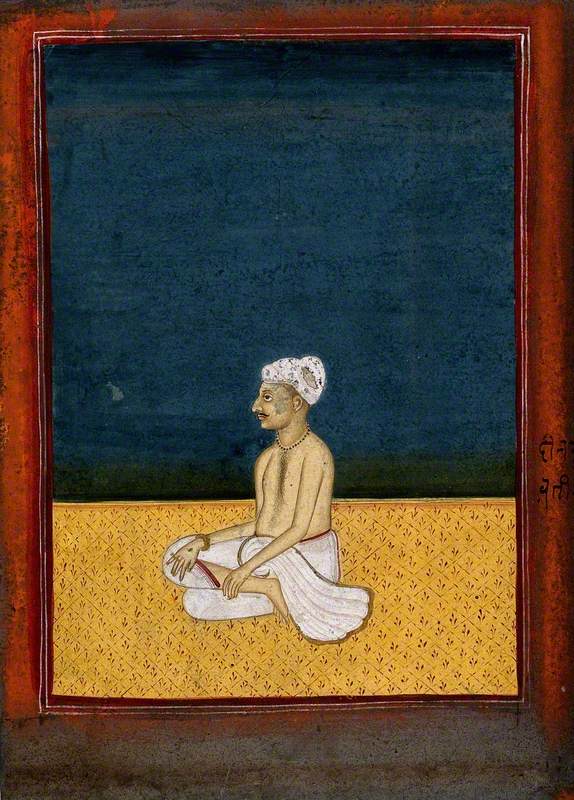

opaque watercolour on paper by Samuel Fyzee-Rahamin (1880–1964)

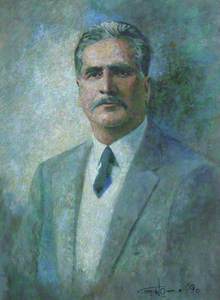

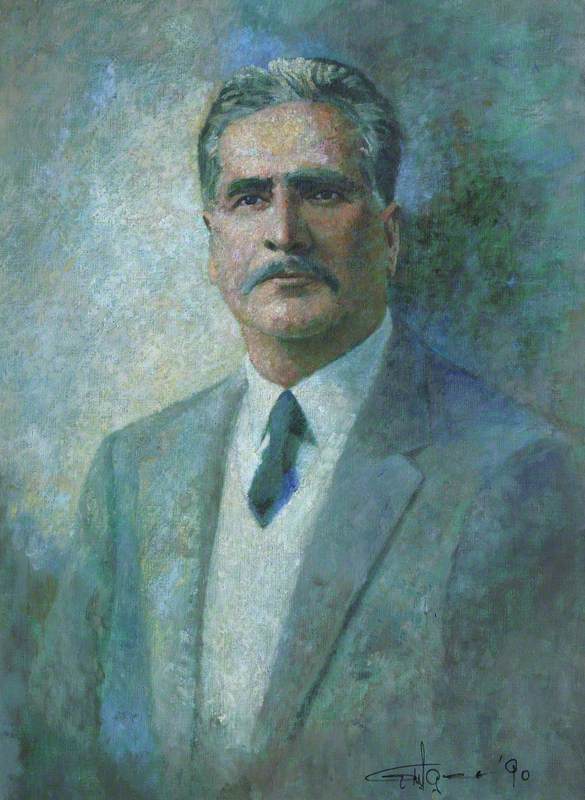

Her name is most notably associated with her 1947 biographical account of the iconoclastic poet of Pakistan, Muhammad Iqbal, one of the few primary reflections of Iqbal's time in Europe.

Muhammad Iqbal (1877–1938), Philosopher and Poet

1990

Ismail Gulgee (1926–2007)

It is a reflection and compilation of her journal entries and travelogues of her time in London, meeting Iqbal in 1907 and travelling to see him during his studies in Germany. Yet, her legacy in her own right is significant, as a sculptor of cultural and academic thought of this generation.

Through brief interactions with both Iqbal, the poet-scholar Shibli and others, her hypnotic aura is clear. Both Iqbal and Shibli entered liminal relationships with her – writing to her as a muse, for advice, as a confidant and even to proof unpublished works. Through her correspondence with figures like these, and travelogues written prior to her marriage, her presence as a creative, connective and critical mind engaged constantly in finding place and problem in Western modernity. It is most likely that the arrival of Atiya Fyzee into his life pushed Samuel Fyzee-Rahamin to become the artist he became.

It was after his marriage that his painting style that is represented in UK collections begin to appear. His recognition as an artist increased and his name can be traced across Europe for almost two decades in group and solo shows. In 1914, he had exhibitions in Galerie Georges Petit, Paris and Goupil Gallery, London. In 1918 he was present in New York, holding a show at the Knoedler Gallery. In 1924 his works were present in the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley.

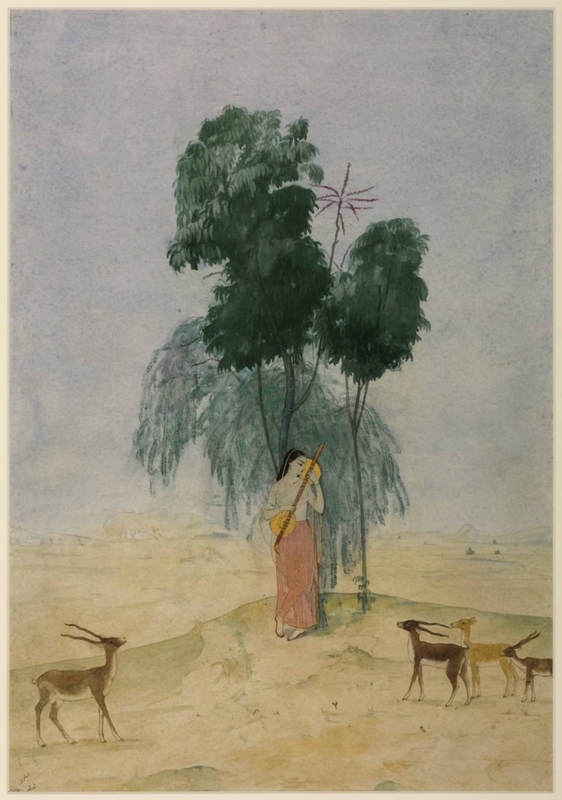

In 1925, his first work entered the Tate collection, presented by Sir Vincent Sassoon. The painting, Raagni Todi, Goddess Tune, marks the first representation of Fyzee-Rahamin's work in a national art collection in Britain.

In many of these exhibitions, Atiya Begum's presence is there – as creative collaborator and/or through her networks. In New York, she held a programme of song and music alongside the exhibition – likely the same in the Paris and London shows. In fact, Goupil Gallery published a book co-authored by Atiya and Samuel titled Indian Music – an allegorical and analytical dive into the forms, functions, and mythologies of classical Indian music, with paintings by Samuel. It was fine-tuned and republished in 1925 as The Music of India, now authored solely by Atiya.

Title page and frontispiece of 'The Music of India'

Written by Atiya Begum Fyzee-Rahamin, published by Luzac & Co., London, 1925

In the 1925 publication, Atiya describes how the words and paintings included, were developed in a time the couple spent in a fishing village near Bombay in 1913:

'I sang the eternal limpid melodies. Rahamin immortalised them in a series of beautiful paintings, the ragas and raginis. I dashed off a few lines in explanation. We soon left for Europe, where the written text was brought out in book form, and helped to explain the symbolic significance of the ragas and raginis.'

Atiya and Samuel Fyzee-Rahamin

c.1912, photograph by an unknown artist

By the end of the 1920s, Samuel Fyzee-Rahamin had become a hugely recognised artist in India and in Europe. Between 1926 and 1929 he undertook a commission to paint a monumental fresco in the government Secretariat building in New Delhi – embodying plays on form and subject, reconsidering and amalgamating traditions of both 'West' and 'East' – both in terms of technique and mythologies.

In 1930, Fyzee-Rahamin had his most noted exhibition in Britain. Manchester Art Gallery put on a solo show, titled 'Exhibition of Decorations for Delhi'. It was a complete retrospective that represented three broad strands of his practice since returning to India after his studies – his early portraiture of the Indian nobility, his miniature scenes of Hindu and Muslim mythologies, and an array of planning sketches and drawings for his frescos and murals.

It is a truly remarkable moment to consider, this solo show by a public art museum in Britain, of an Indian artist – particularly in relation to how lackadaisical British art museums still are in acknowledging artists outside the dominant culture. As of 2021, Tate Britain, for instance, has yet to hold a solo show of a South Asian artist.

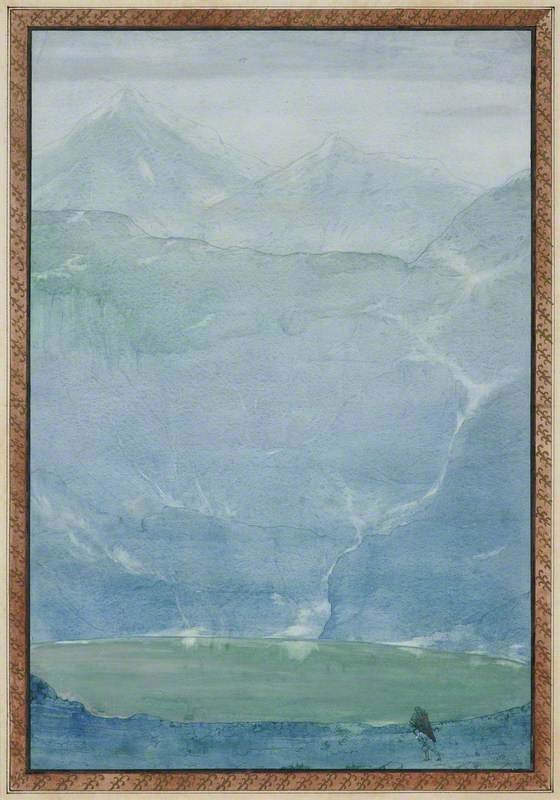

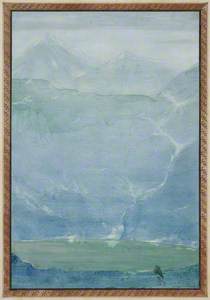

The painting Ali Pathar, Kashmir that is now part of Manchester Art Gallery's collection was acquired from this 1930 solo show.

In the late 1930s, Samuel and Atiya turned their attention to literary endeavours in London, co-authoring and putting on at least two plays. The 1938 play Invented Gods, for example, touches upon class, religious tradition, gender roles and Western notions of liberation/imprisonment of sensibilities. It synthesised their views of a world where both tradition and modernity nourished each other for the betterment of humanity, for the betterment of India.

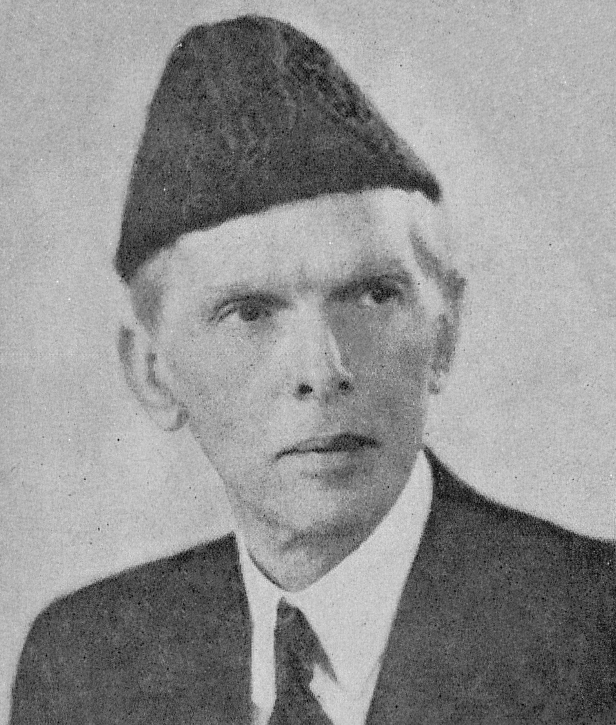

This idealised hope that they largely explored across Europe perhaps lay in contrast to their decision to move to Pakistan in 1948 to be part of the formative cultural administration of this new nation – a personal invitation by Jinnah.

Muhammad Ali Jinnah

Frontispiece to 'Muhammad Ali Jinnah: A Political Study' by Matlubul Hassan Saiyid, published by Shaikh Muhammad Ashraf, Lahore, 1945

Initially opening their government house in Karachi to double as a cultural centre, and growing and nurturing a collective of writers, artists and other cultural interlocutors of Pakistan, their hope turned cold after falling out favour with a powerful government administrator after just a couple of years.

In the years after Jinnah's death, and after a disagreement with senior government officials, they lost the government house and roles they had been given. Through the 1950s and to their deaths in the 1960s, they lived in quiet lives – relying heavily on the generosity of family, friends and past connections. Samuel passed away in 1964 and Atiya in 1967. An unrealised museum in Karachi to their art and cultural legacy exists half complete – a project long abandoned, a somewhat reflective monument to their art.

This snapshot of a rich life of an artist traversing Britain and India in the early twentieth century through to independence and Partition is a true gift to have represented and be presented in UK public collections. Yet what a wasted gift, as it remained an anomaly in the collection, outside the canon of British art history.

Today Black or Asian artists are usually only associated with British cultural memory from the 1960s onwards – as referenced by 'The Other Story', the 1989/1990 exhibition at the Hayward Gallery curated by Rasheed Araeen.

Exhibition guide 'The Other Story: Asian, African & Caribbean artists in post-war Britain' 1989 Hayward Gall. Aubrey Williams family gift pic.twitter.com/XdgTVBnvcV

— Stuart Hall Library (@StuartHallLib) January 26, 2017

But Samuel Fyzee-Rahamin's work is from an earlier time. The lack of widened perspective in the curatorial professionalism of Britain has put his work in the shadows. It makes it hard to see how relevant his story is, and how important his presence in the national collection is, alongside the symbolism of including him as an artist living and working in pre-war Britain.

When I first took his archive file out at Tate, I was moved to tears to connect with this presence of Muslim South Asian experience in British art history over a century ago. Yet, that sadness and anger weighed my heart to the ground in seeing the contents of that file. It is mainly keepers of the collection enquiring as to why the work is in the collection and to attempt to shed light on any meaning or context of the paintings.

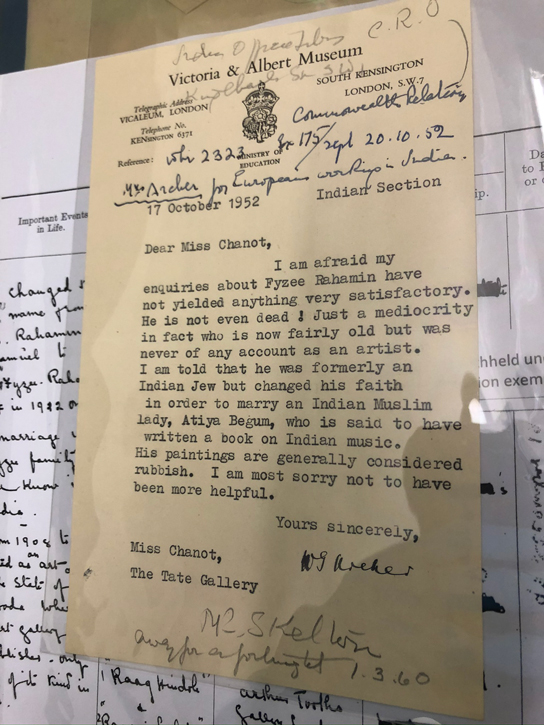

A letter from the V&A 'Indian Section'

1952, Tate Archive

A 1952 request to the V&A's 'Indian Section', seen then as the foremost authority, asks for context on Samuel Fyzee-Rahamin and the artworks in the Tate collection. It yielded a response that stated he was a 'mediocrity' and 'was never any account as an artist'. The note goes on to say his paintings are 'considered rubbish' – a remarkable position considering his success both in India and Britain just two decades earlier.

In the same year, the Pakistani government published the catalogue Pakistan Miscellany, a survey of Pakistan's history and culture – which dedicated an entire chapter to Samuel Fyzee-Rahamin. In another exchange of correspondence, now in the late 1970s, another Tate keeper of collections takes up the task of trying to source more information. This time their correspondence is met with the news that the artist passed away in 1964.

The legacy of Samuel Fyzee-Rahamin and his creative partner Atiya Begum should be a cherished and lauded part of Britain's art history. It is a true gift that there is a literal presence in UK public collections of their work and legacy as artists – yet the way it has been fragmented out of coherence by these very frameworks that have canonised what is relevant is so telling.

If Samuel Fyzee-Rahamin – an artist who had institutional reverence, who held space within public collections and archives, and who had even been educated in the formalised Western art tradition – was not processed into the cultural memory of this country's art history, what hope did anyone else have? How many artists outside the dominant culture would never come close to institutional recognition or a place in collections? How many artists of great standing have been dismissed as 'rubbish' by authorities like the V&A? How limiting is the expertise and experiences that have defined what matters to British art?

Looking to this past we can hope that our institutions in the present are continuing to open space for wider and more diverse experiences and expertise to contribute to deciding what matters – what is important to Britain's cultural memory. We can hope that our institutions continue opening their doors, and particularly their hearts, to think of a future that gives life to inclusive canons of art history.

Hassan Vawda, writer and researcher