Much like the Brothers Grimm stories in Europe, One Thousand and One Nights is a collection of tales told in Asia. Originating from around the Middle East, these are stories passed on through generations – edited, altered and restructured to reflect peoples' dreams and lives, and the culture of each time. After centuries of these stories being verbal only, storytellers started to compile them, to eventually form what we now know as the One Thousand and One Nights (or, as it's often referred to in English, Arabian Nights).

Even though not entirely thematically suited for young ones, most children brought up in South East Asia and the Middle East are familiar with these stories. Some of the most popular tales are familiar across the world, including those of Sinbad the Sailor, Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, and Aladdin and his lamp. Though Aladdin, as we know the story, is not part of the original 1,001 tales, the motifs presented within his story – magical flying carpet, wish-granting genie – are heavily represented in other tales.

In an early example of a 'framing device', it is Scheherazade's story and narrative that binds together the rest of the 1,001 stories.

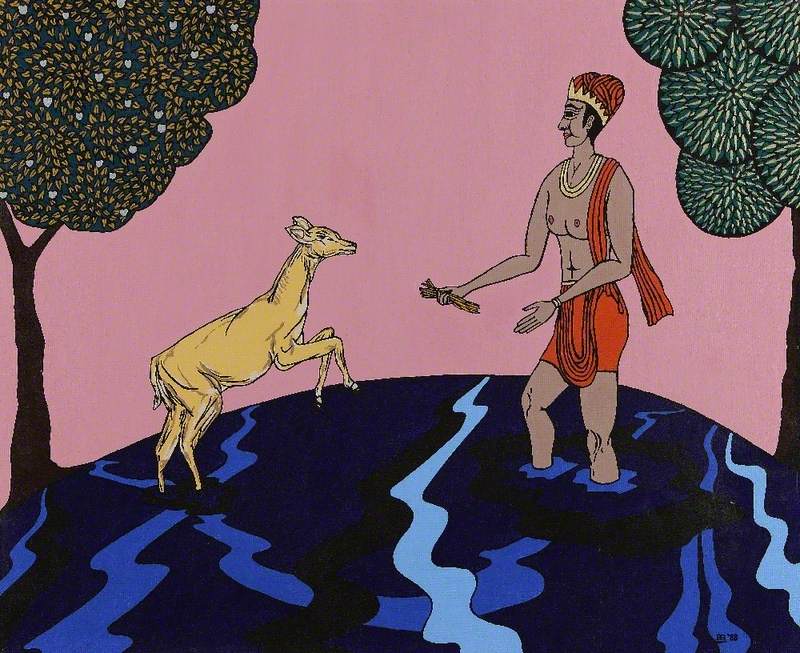

Sinbad in the Valley of Diamonds

1878

Albert Goodwin (1845–1932)

So, Scheherazade – who is she? Once upon a time, a sultan of a big and powerful empire left his castle to embark on a hunting trip. Returning unexpectedly early, he caught his beloved wife in bed with servants. Enraged, he beheaded them on the spot and made for the estate of his brother, who was away at the time. He decided to stay in one of the outhouse guestrooms. Here lay his next staggering revelation: past midnight, he started to hear music from the gardens and open windows. Exploring, he was shocked beyond belief to find his brother's wife among a small crowd of nude figures, dancing in the moonlight and indulging in desires.

Stunned by the turn of events, he returned to court blinded with a desire for revenge. Engrossed in feelings of betrayal and rage, he vowed to take revenge on all womankind by beginning a monstrous tradition: he would take a new virgin wife every night, only to behead her the following morning, so as to not allow her the opportunity to cheat.

In the sultan's madness, the kingdom slowly became a hostile place for all young women. Families fled elsewhere with their daughters as the sultan continued with his rage-filled murder. Sick with worry, the vizier urged his daughters to leave. He had to stay in the capital and fulfil his duties, but his two daughters, Scheherazade and Dunyazad, could flee. Here the story gets interesting, as Scheherazade refuses to leave – and instead insists on becoming the sultan's next bride.

After many attempts to try and make her see sense, and much to the vizier's dismay, Scheherazade and the sultan were married.

On Scheherazade's wedding night, as a last wish, she begged for her sister's company. Dunyazad joined them and requested one last tale from her sister. With the sultan's approval, Scheherazade started her very first story. So captivating and mesmerising were her charm and her storytelling capabilities, it was almost dawn before anyone realised. Clever Scheherazade ended the night's storytelling on a captivating turn, leaving her audience on edge, wanting more. The sultan was so engrossed in Scheherazade's story that – to everybody's surprise – he allowed her to live one extra night to finish it.

Of course, the following night she finished the first story – and began another one. She continued this night after night, always ending on a tantalising twist. Scheherazade continued telling her tales for a thousand and one nights, and in that time the sultan slowly started to fall for her beauty, charm and intelligence. He eventually saw the error of his ways and the injustices he'd wrought. Professing his true love for Scheherazade, they finally began a life together. The bloodlust stopped, and peace was restored.

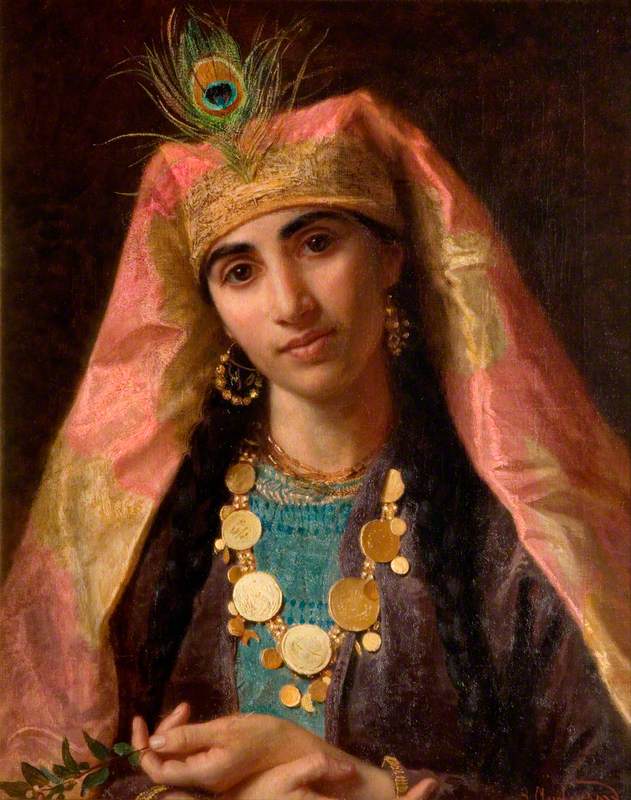

The creator of this painting is Sophie Gengembre Anderson, a British artist born in France. Heavily influenced by Neo-Classicism and Pre-Raphaelitism, Anderson's work reflected both styles and often included rosy-cheeked children. Due to most of Anderson's themes being considered 'sentimental', and her tendency to illustrate home life, women and children, her work sometimes gets written off as kitsch, or as 'just for women'. This suggestive notion – that Anderson's paintings can only be enjoyed by women – is a preposterous thought. Most of history has been told, painted and recorded by – and one could argue, for – men. During Anderson's time, exploring themes that would interest and include female audiences as much as their male counterparts was a pioneering concept.

As well as France and England, Anderson spent some time travelling and living in the United States with her family. During her later years, she moved to Capri for health reasons. All her travels informed and influenced her art and she was known for her interest in painting local people. However, there are no records of her travelling to the Middle East in her lifetime. Sir Richard Burton's translation of One Thousand and One Nights was published in 1885 and very likely interested Anderson. Victorian indulgence and obsession with exotic tales and culture at the time made these stories a very popular motif.

In the painting, we find Scheherazade in a traditional Victorian portrait posture. Her long, dark hair is separated into two braids, and the jewellery and fabrics she is adorned in celebrate traditional Arabic culture and garments. It is interesting how Anderson did not paint her with too much glitter and glamour: Scheherazade comes off as a character from a relatively well-to-do family, but not quite a queen yet. The peacock feather on her head is incredibly interesting. With a metaphorical all-seeing eye, peacocks hold the status of a sacred emblem. The feather represents a pure soul, the one that cannot be tarnished.

In the soft light, Scheherazade's facial features are brought out with a kind resonance. There is patience in her eyes, perhaps hinting at her persistence through the 1001 nights of storytelling to please the sultan.

Bristy Chowdhury, writer

Enjoyed this story? Get all the latest Art UK stories sent directly to your inbox when you sign up for our newsletter.