Sean Scully is teaching me how to snap my fingers.

Or, I should say, how to cheat at it. It's the cool way to snap where the top finger strikes the middle finger with a flick of the wrist. I have never been able to do it – but it turns out – neither has he. He clicks his left hand at the same time, giving the illusion of snapping success with his right. 'The kids go crazy for this.' He tells me that his ten-year-old son, Oisin, tries the cheating method too but can't get the timing quite right. 'It's adorable when he does it.'

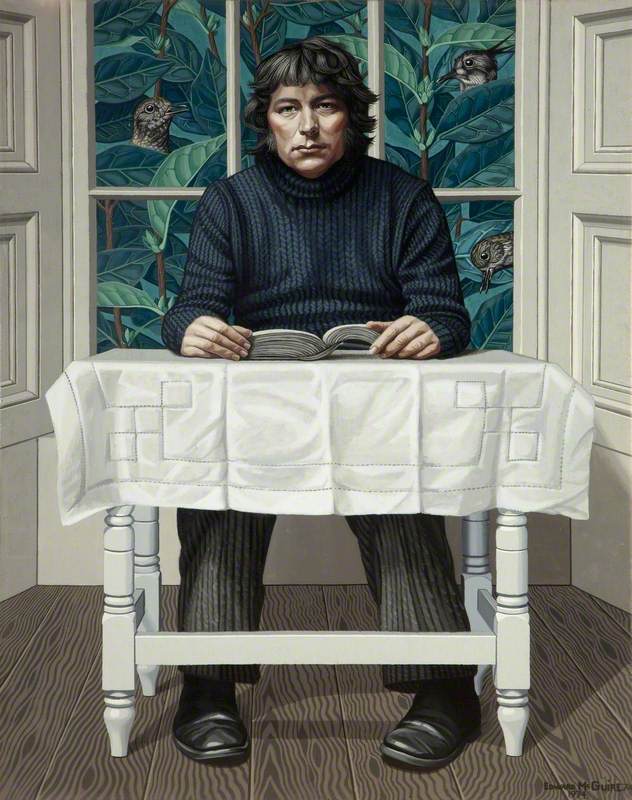

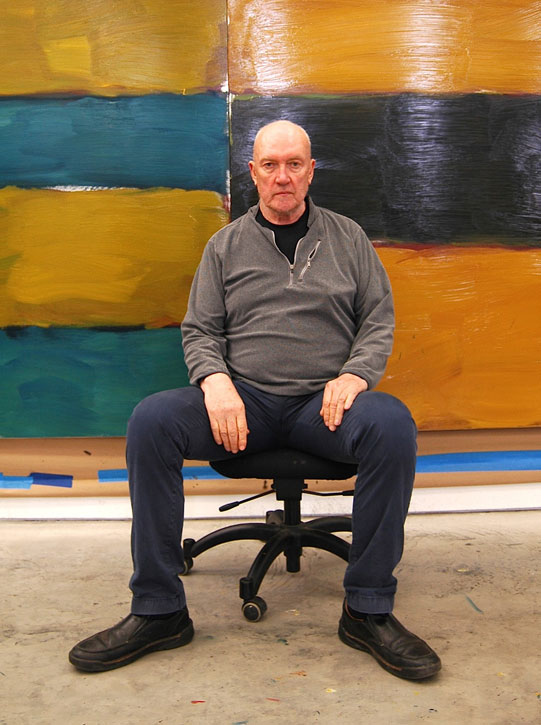

Sean Scully in his studio

I am profoundly aware that this chat with Sean is like having Picasso teach you how to whistle.

At 74, Sean Scully is one of the most important abstract painters working today. He has two magnificent studios, in New York and in Berlin, which I have visited, and a further one in Munich. Though he is listed online as an Irish-born American artist, his accent sounds to me more South London than anything else, entirely rough around the edges. 'On my birth certificate, my father's occupation is listed as 'Traveller'. But that's what we were. We were gypsies.'

In the 2019 BBC documentary Unstoppable: Sean Scully and the Art of Everything, one can watch the story of Scully's meteoric rise in the art world as the film crew follows him around the world from one exhibition opening to the next over a period of about twelve months. It is a rags-to-riches story of dizzying proportions. From near destitution to five-star living.

His paintings are represented in museums around the world. Name it, they will have a work of Scully's in their collection. And if they don't, they are trying to get one. But I am here to talk to Scully about what feels like a new phase in his career. Though not new to sculpture, Scully has recently been producing more for public view.

'Sculptures don't come out of sculpture, they come out of hard work,' Sean says in his slow, crisp, direct tone. 'When I had the space, I started to make them for myself. I didn't make them for other people. Then people started to like them, and I responded to public demand really.'

I have learned from long observing his paintings and hearing him talk about them, that unlike minimalist art or other abstract painting, Scully's brand of abstraction always has a narrative.

Behind each one of his images, is a backstory that makes the work more relatable to the viewers.

'The example I would give is jazz. If you listen to jazz and you listen to John Coltrane for example, and he abstracts My Favourite Things.' Scully hums the familiar song to a syncopated beat before suddenly scrambling all the notes to a nonsense jazz-babble. 'People don't like it. And what saves John Coltrane is the familiarity of the thing he is abstracting so then you can relate it back to that. But to go into jazz which is abstract, and it was socially connected to abstract painting in the '50s, requires a leap of faith. Or it requires a level of education so that you can understand it.'

Is that the case with your sculptures? Do they also follow in that line of familiarity before the abstraction?

'You must read my essay 'Loading a Truck',' Scully tells me. And I did. It is a short story of workmen, two are illiterate and sign they wage slip with a cross, who stack flattened cardboard boxes in cold hard conditions. It is a short, heroic poem-like-text of hard labour where the work results in a tower of tan shapes. The memory of the resulting 'sculpture' is what Scully creates in his art. The abstracted two-dimensional version of the boxes in his paintings will be familiar to the workmen, if not immediately obvious why.

Scully explains: 'Sculptures are more accessible, and the reason sculpture is so popular in England is the same reason abstract painting is not. Because the effort to decode painting is something that has not been nurtured by the art establishment. Sculpture doesn't really need any decoding because it is already a thing. This is the problem. Two-dimensional painting is a three-dimensional thing made flat. Even in figurative painting, what you are painting is three-dimensional.'

And this is the reason he offers as to why he no longer lives in the UK.

'I love London. I'm crazy about London. But the art world in London is something that I am at odds with.'

'The UK is a lowbrow culture, with the exception of certain literature. I know it drives everyone crazy in the UK when I say things like this,' he says sincerely. 'They know a lot about Shakespeare who was the greatest writer who ever lived. They are educated so no one can say 'I don't like Shakespeare; I don't understand nothing'. If you say that then all the guilt falls on you. But if you say, 'I don't like abstract painting' then all the guilt falls on the abstract painting.'

Should museums be doing more to address this gap?

'Absolutely, if they want to have more abstract paintings. If they don't then leave it as it is, and it can be a culture free-zone. The problem is the education. In Spain or Germany or even America, there is an education on how to look at it and how liberating it can be.'

Last year, in 2019, for his exhibition at San Giorgio Maggiore for the Venice Biennale titled 'Human', Scully created a towering sculpture Opulent Ascension that one could walk into.

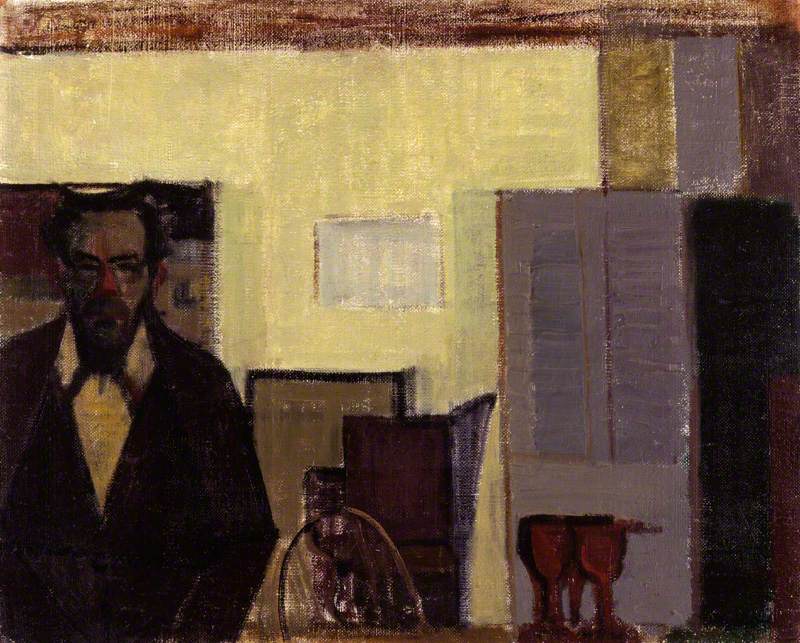

Opulent Ascension

2019, felt on wood by Sean Scully (b.1945), San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice

Standing inside, one's eyes were drawn up the stripy walls, like ladders, to an open top, focusing the eye on the light coming through the glass dome of the chapel. It was hard not to see it as a religious metaphor. Was this intentional, considering the setting?

'I'm willing to accept it as a religious metaphor if one can concede it as nondenominational. Some people ask me "what are you as your work carries an obvious spiritual quality?" I say that I am Catholic with a strong Buddhist underpinning.' Sean laughs. 'You will never get a straight answer from me when it comes to religion because I'm all in, but not all in with the narrative. What it is, is a spiritual metaphor because when you look up at it, the light at the top makes a star. That's looking at the heavens. And of course, I was thinking about religion and the idea of ascension, but I also made an ironic remark about Catholicism because I called it 'opulent' ascension. So, it's a little game going on there. I think the title is fantastic because the skin of the felt becomes something else. It makes it something else.'

View of Santa Cecilia chapel, Montserrat, Spain

Walking into Santa Cecilia, the church chapel Scully designed in Monserrat near Barcelona, was like walking into one of the Wall of Light paintings.

The windows, a coloured glass that you designed, flooded the space with light.

'Well there you have described my sculpture yourself,' Scully responded softly. 'If Mickey Mouse was me, and Mickey Mouse wanted to make one of my sculptures, it would be a beautiful Walt Disney cartoon because all the blocks would come off my painting and off the wall and start reassembling themselves three-dimensionally in the middle of the room. And this is how I think. It was easy for me to make sculpture. I couldn't get it wrong.'

In 2018, the Yorkshire Sculpture Park organised an exhibition called 'Inside Outside' which had some paintings in the Longside Gallery, and sculptures dotted around the park grounds, two of which, Wall Dale Cubed and Crate of Air, were commissioned especially for the park.

'Crate of Air is like an abandoned city. It's 'bones of the building' is one way to look at it. With Wall Dale Cubed, it's really material that's in the ground and I just move it to somewhere else. That's basically what I'm doing. I always turn it into blocks. Blocks of where I compress all the space so that they have this inner mysterious quality which relates to the paintings because the paintings are made with layers and the stone ones are rather similar.'

'My sculptures really relate to stacking and industrial work. They are very proletarian. Like in 'Loading the Truck'. I worked in loads of building sites in my life and I framed out my own loft in New York. I used wood mostly in those days. I did use metal as well but when you start framing it out it makes this incredibly beautiful drawing before you cover all the walls. In the end, you are hiding all the beauty to make it respectable or habitable but before the walls are covered with sheetrock, a building site is the most beautiful thing you have ever seen. It looks like a church! With all the dust and light coming through, and all the structure. So, my Crate of Air is really from that. It all comes from work. From hard industrial work.'

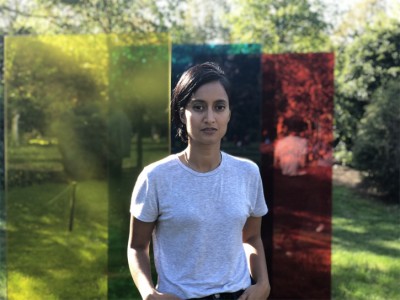

Maya Binkin and Sean Scully

I love your stone sculptures, such as Wall Dale Cubed. I think they are a lot about time, which is hard to do with sculpture.

'My sculptures are in a sense more original than my paintings.'

Well, sculpture is usually a frozen moment in time, but your stone works seem to extend time. They are timeless, large, heavy, they seem to be tired. Like they are exhaling for a millennium.

'Yeah. They will last thousands of years.'

Maya Binkin, founder of The Art Pilgrim