In the series 'Seven questions with...' Art UK speaks to some of the most exciting emerging and established artists working today.

'I live in my own funny little world' the artist Anne Rothenstein confesses – a state of being she has apparently dwelled in since childhood. Raised in the village of Great Bardfield, Essex, she is the daughter of two well-known artists in their own right, Duffy Ayres and Michael Rothenstein. However Rothenstein, rather than training to become an artist, abandoned her brief studies at the Camberwell College of Arts in the 1960s to pursue acting instead. Only later in life did she pick up the paintbrushes and to return to her love: oil paint.

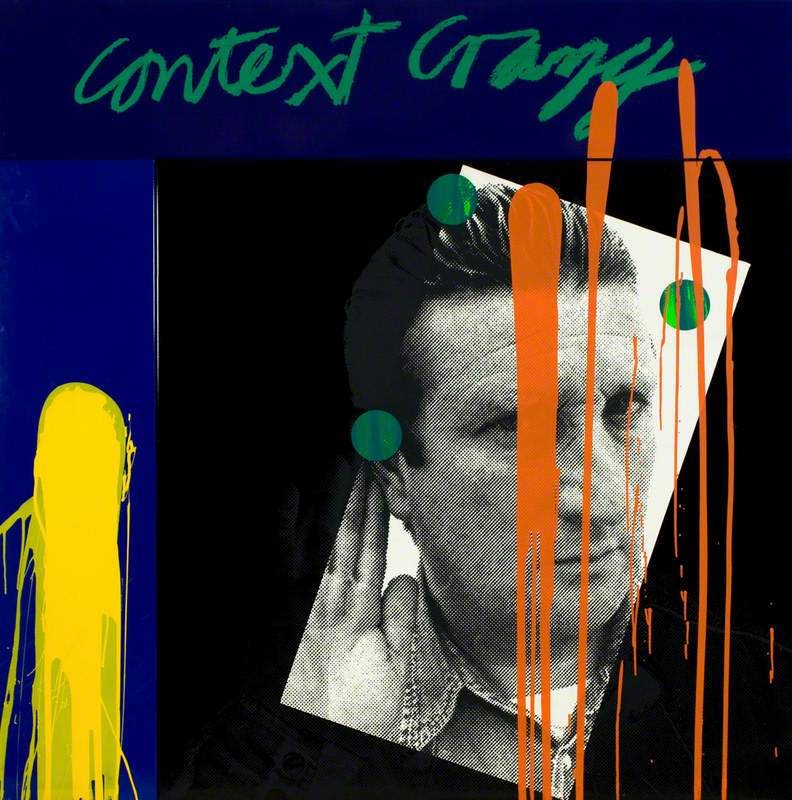

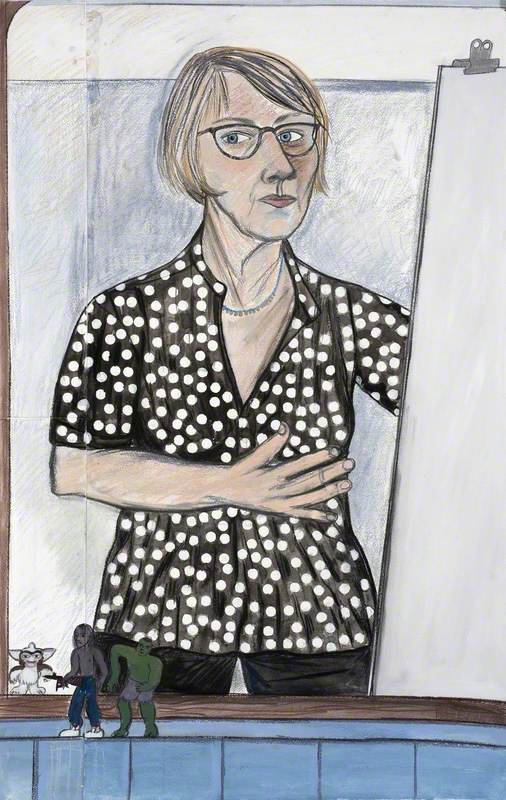

Bruised I

2021, oil on wood by Anne Rothenstein (b.1949)

The painter, now in her 70s, is having something of a moment on the British art scene. Her latest solo show at Stephen Friedman Gallery – announcing her representation with the gallery – presents a body of new work, a series of enigmatic paintings articulating Rothenstein's long-term preoccupation with unidentifiable and solitary figures in psychologically charged environments.

Intuitively rendered, the artist's paintings and collage works evoke a sense of mystery and longing – her protagonists yearn for something intangible, beyond the frame. As viewers, we are left to imagine the narratives subtly evoked through each flattened composition, as we dive into her surreal and melancholy world.

Art UK spoke to the artist to coincide with the opening of her exhibition.

Lydia Figes, Art UK: The works from the Stephen Friedman Gallery show were created over the past two years. With so much going on in the world, was this a challenging or productive time for you creatively?

Anne Rothenstein: Working during the pandemic was strange, but at the same time I lead an incredibly solitary life, so in that sense, it almost didn't affect me (except for washing my shopping when returning from the supermarket!).

I've always painted solitary figures, but I did become more aware of how other people live during the pandemic. I live on my own, and in my own funny little world, but the pandemic encouraged me to look outwards. My studio is in a block of flats in West London, so day in and day out I was looking out into my neighbours' windows and seeing that sense of claustrophobia.

Moonlight

2021, oil on wood by Anne Rothenstein (b.1949)

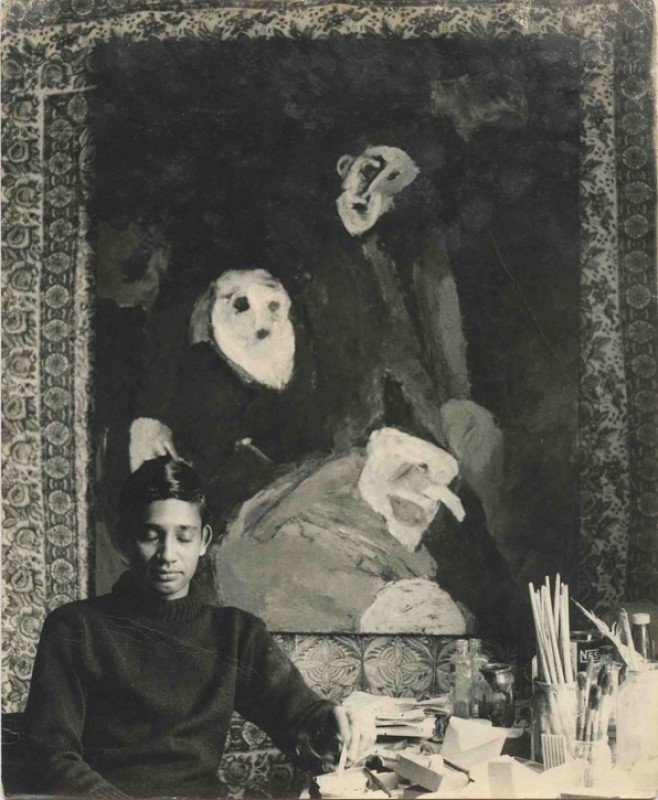

Lydia: You come from an incredibly artistic family, your mother was Duffy Ayres, your father Michael Rothenstein, and your grandfather was the Royal College of Art principal Sir William Rothenstein. What was it like growing up in that world?

Anne: Until I was 7, I grew up in a small village called Great Bardfield. It was full of artists, for example Edward Bawden lived across the road, and Eric Ravilious also lived there before the War. The weird thing was, although the place was shaped by artists, that community was deeply conventional. It wasn't a bohemian village, which is how some people imagine it. It was just quite normal. I also didn't know any different.

As a child, I was never dragged to art exhibitions or anything like that. In those days, children were sort of excluded, we were a nuisance. As a very young child, I spent most of my time alone. I lived in my own world at the bottom of the garden. I painted, drew and wrote all day long. Of course there were always materials all around me to do things like that, and in those times we didn't have television. It would be unusual to get through the day without producing or creating something.

Unknown Territory 2

2022, oil on wood panel by Anne Rothenstein (b.1949)

Lydia: Did your parents encourage your creativity?

Anne: Not particularly. Possibly due to being a girl, I was slightly ignored. My brother probably has a very different story – he certainly spent more time with our father in his studio. There were more expectations on him. In that sense, it was a conventional household. My mother helped my father work before she picked up her own paintbrushes.

Lydia: Who were your early artistic influences?

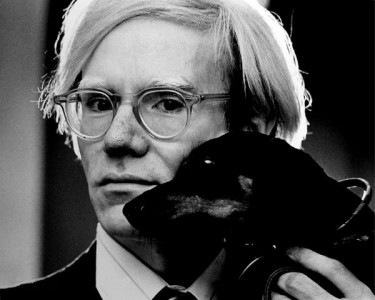

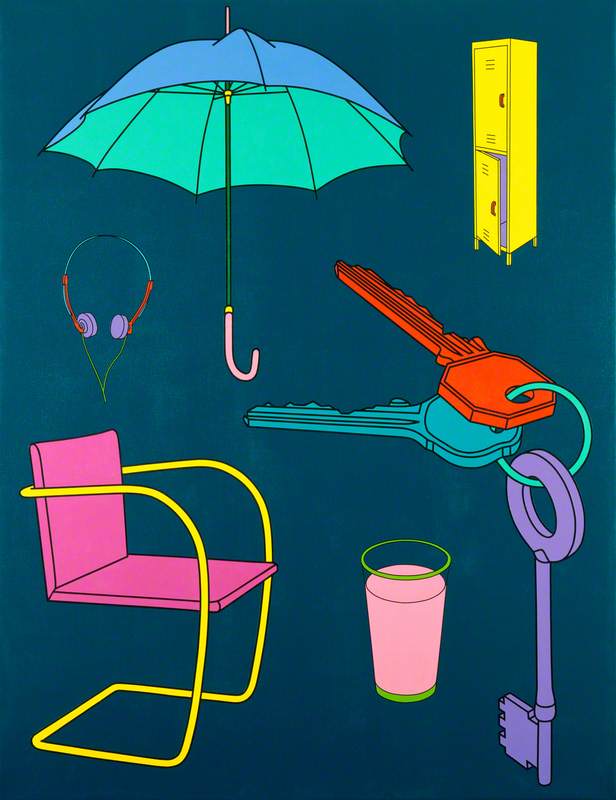

Anne: When I went to art school in the late 1960s, we were all obsessed with Andy Warhol and Pop Art. Nobody was very interested in painting, which is possibly why I quit. I've always loved paint – oil paint is one of the most wonderful things in the world. My art school teachers told me I should do graphics, because in those days lots of women became illustrators, it was the era of Pauline Boty and people like that. I only really became influenced by other artists when I began to paint again in my 30s.

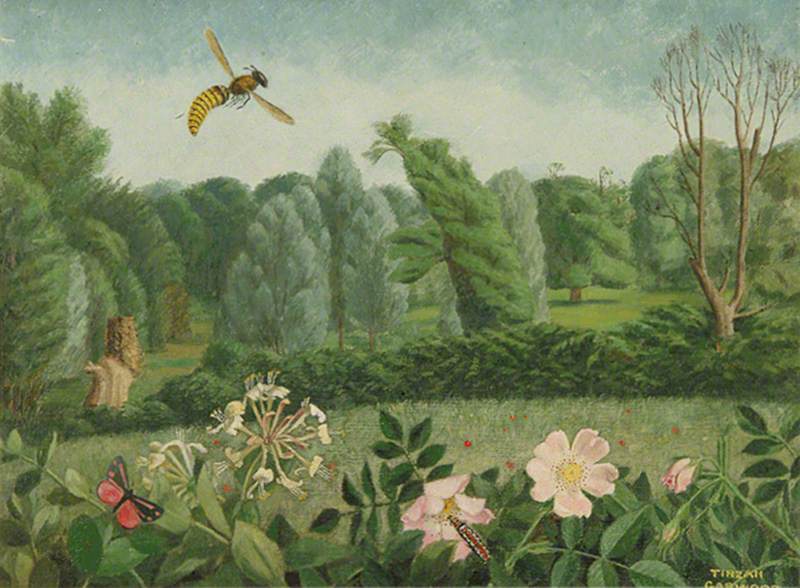

My main love is Outsider Art, which is perhaps a reflection of how much of an outsider I've always felt (even though you could say I was born inside). Artists like Malevich and Natalia Goncharova have always interested me... and I've been very moved by the paintings of Gwen John. I wouldn't say that I reference her stylistically, though she also painted many solitary figures. I love early David Hockney, especially his etchings and drawings. Milton Avery has always been an influence. Over the past ten years I have been incredibly inspired by contemporary art and artists, names like Mamma Anderson, Rose Wylie, Kiki Smith, Noah Davis, Kerry James Marshall. I had a visceral reaction to the works of Bill Traylor, the African American folk artist.

Lydia: Why do you think you identify with Outsider Art, even though you were born within artworld circles?

Anne: I think because my parents appreciated it. Nothing about my upbringing was particularly intellectual, my pursuits have always been instinctual, which is perhaps something I share with outsider artists. I'm not terribly interested in art history or the great classical artists. I'm moved by the work of outsider artists. Even the paintings of a child can move me profoundly.

Lydia: The work Bruised 1 is quite interesting in that it suggests a narrative beyond the painting, although you usually work in an intuitive way?

Anne: I had seen a drawing that inspired this work. Although I work instinctively, usually I have seen either a drawing, photograph or painting that helps conjure an image in my head. I'll start working with a reference in mind, but then the painting takes on a life of its own.

I was very impacted by Nan Goldin's self portrait from the series The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, and I only realised after finishing the painting that perhaps this image had crept into my painting. That particular work I regard as a thing of extraordinary power, beauty and ugliness. Goldin's image perhaps shaped the work, but I hadn't set out to paint a damaged person.

In another earlier work, Figure on a Bed, the figure was also painted intuitively. But upon reflection, this was created at a time when I had a young family. I think the work captured my exhaustion. I don't set out to create images of figures that are based on myself, but to some degree, you could say all my work is a loose self-portrait.

Lydia: As a self-taught artist who has found success today, looking back, do you ever wish you went to art school?

Anne: Absolutely not. I love that I taught myself what I know. There have been no restrictions. I like learning as I go along.

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

'Anne Rothenstein' at Stephen Friedman Gallery, London is open until 5th November 2022