In the series 'Seven questions with...' Art UK speaks to some of the most exciting emerging and established artists working today.

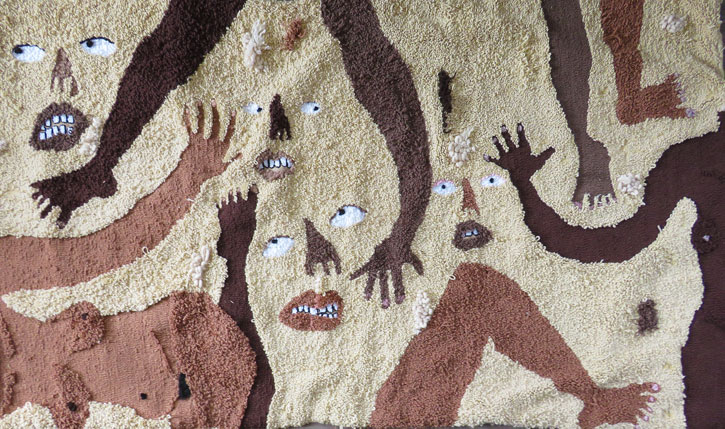

Anya Paintsil's distinctive works are hard to miss. Her allusive textiles immediately grab attention for their sheer originality and refreshing take upon a medium that has often been dismissed.

Metaphorically and materially, Anya's work pays homage to her Welsh and Ghanaian heritage. Often titled in Welsh and focusing solely on Black figures, her work confronts assumptions that to be Welsh means to be white. Her works weaponise humour as a way to attract the viewer, but also convey a darker ambivalence.

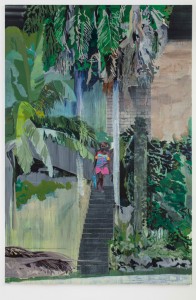

God will punish him

2021, textiles by Anya Paintsil (b.1993)

Born in Wrexham, North Wales, but now based between Manchester and Chester, Anya's work proudly utilises historic rug-hooking techniques passed down by generations of Welsh women in her family, while celebrating the innovation of Black and Afro hairstyling. Hair is a central motif in Anya's work and, in particular, the loaded cultural and political implications of having Afro hair in a predominantly white country. By regularly cutting off her own hair for inclusion in the work, Anya physically and symbolically weaves herself into the fabric.

Historically, embroidery and textiles have been relegated to the feminine and domestic spheres, something Anya consciously references. But she also speaks to the present, challenging assumptions within contemporary culture. For example, that hair (and in particularly Afro hair) doesn't belong on the walls of the white cube gallery space, or that Afro hairstyling can't be regarded as a 'high' art form.

Her works may be charming and soft, but they hold the potential of a political punch, a feeling that lingers long after first encountering them. I spoke with the artist to get a better understanding of her practice. Continue scrolling to read the full interview.

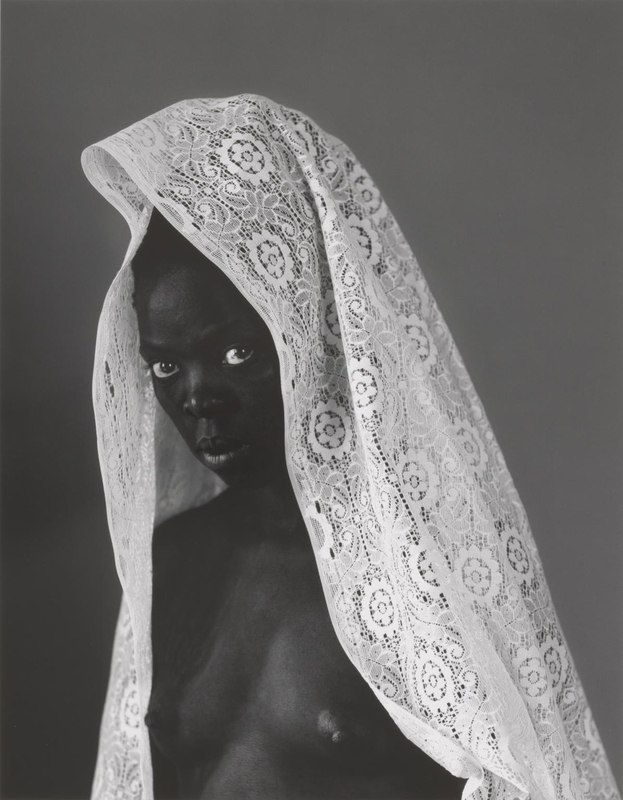

For Levi, Beware the Woman Dog and Her Babies

2021

Anya Paintsil

Lydia Figes, Art UK: When and how did your distinctive style come to fruition?

Anya Paintsil: Different strands of my practice came together at different times. Like the way I focus on the body, visualising the 'self' through self-portraiture, or the way I choose figures and facial expressions. Portraits of people I know have been a constant throughout my practice, and in general, the themes in my work have stayed the same – that interest was there before I began making art professionally.

I didn't study art in school and didn't study art again until I went to university. But it was always in the background of my life and something I wanted to keep private. When I was 23, I wanted to pursue art seriously. But at that time, I didn't have the qualifications to go to university, so I created a portfolio – I realised then that I had to overcome my fear and show people my work if I wanted to progress. How my art exists in its present form developed in the year before I went to art school, especially the use of hair and latch hooking, a technique I learned from my grandmother when growing up in North Wales.

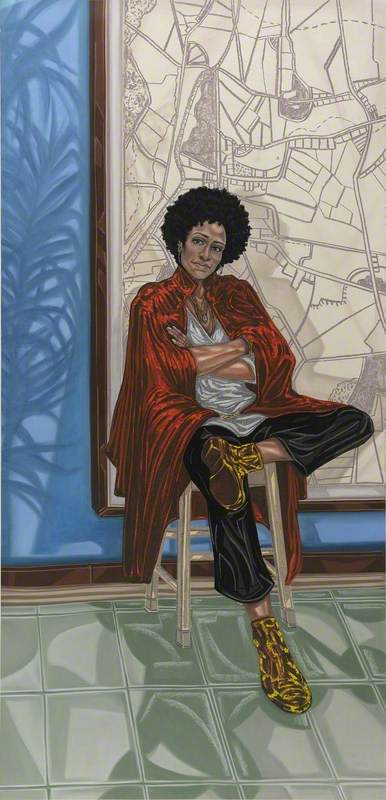

Anya or Anum

2020, acrylic, wool, human hair, kanekalon hair on hessian by Anya Paintsil (b.1993)

I was educated at a Welsh language school where I was one of the few mixed-race students. Pretty much everybody was white, and no one knew how to do Afro hair. My mum (who is white) didn't know how to treat Afro hair. She started to take me and my sister to places quite far away to get our hair done, like Manchester or Crewe. But it's expensive to get braids put in. When I was about nine I learned how to take my own braids out, make them look neat again, and reuse them. Later I began watching YouTube tutorials on how to braid Afro hair. This is how my experiments with my own hair first began. I realised there was a lot of crossover between Black hair techniques and the latch hook rug technique my grandmother taught me. I thought it was really interesting how similar techniques and tools were used for very different things and by different communities.

The origins of the latch hook are unclear, but it was popularised and patented in America in the nineteenth century. In the UK it emerged among millworkers in Yorkshire during the industrial revolution, who were too poor to buy tapestries or embroideries to furnish their homes. Instead, they would collect cuts and yarns and fashion them into larger textiles using the hooked rug technique. It's considered a bit of an 'old lady' or 'old farmers' wife' hobby now. But because it's connected to British working classes and has a long tradition in my family in North Wales and Anglesey it's a craft that feels closely connected to who I am and my culture.

Anya Paintsil

Lydia: Hair is a central theme and medium in your work. Do you feel this is a personal or political gesture, or both?

Anya: The decision to use hair as a material in my work came from a desire to make people reconsider what they think 'art' is, or should be. There is a snobbery when it comes to artistic mediums, and historically craft-based practices have been relegated to the bottom of the hierarchy. Unfortunately, it was not a coincidence that craft and applied arts – usually made by women – were degraded.

So yes, on one hand, using my own hair as a material in craft-based practice has a political motivation. For Black women, hair styling is a huge part of our lives – and we grow up realising that everyone has an opinion about Black hair. We feel scrutinised. When I was a teenager I was embarrassed to wear my hair out publicly, even until my early 20s. I was made to feel ugly for having Afro hair. I had some horrible experiences where people would make comments or touch my hair.

There is so much intricacy, beauty and skill behind the styling of Afro hair – braids, twists, knots. There is innovation behind hair styling, but sadly it is often dismissed as an act of personal vanity, rather than as a creative and beautiful craft. The act of cutting out and working with my own hair is a personal but also political act, in the sense that the Black community often places emphasis on having long hair, or society at large perceives longer hair to be more 'feminine'. Alongside and through my work, I have had a personal journey with my hair.

Lydia: By using hair as a material in your work and then exhibiting the works in a gallery space, you are sending the message that your hair, as part of the artwork, must be respected and not touched. Are you playing on these power dynamics of looking and touching?

Anya: The fact that I can exhibit my work in a gallery context, means that some of that entitlement is confronted – viewers no longer feel that they can reach out and grab or touch my hair as it has now been transformed into 'art'.

Lydia: As a medium, what do textiles allow you to achieve or convey that other mediums cannot?

Anya: I don't think I'd like to work in any other medium, as working in textiles is a huge part of my practice conceptually. The work I make could only exist in textiles, and I wouldn't want it to exist in any other medium. I do create preparatory drawings and paintings, usually small watercolours. This is how I would develop an idea.

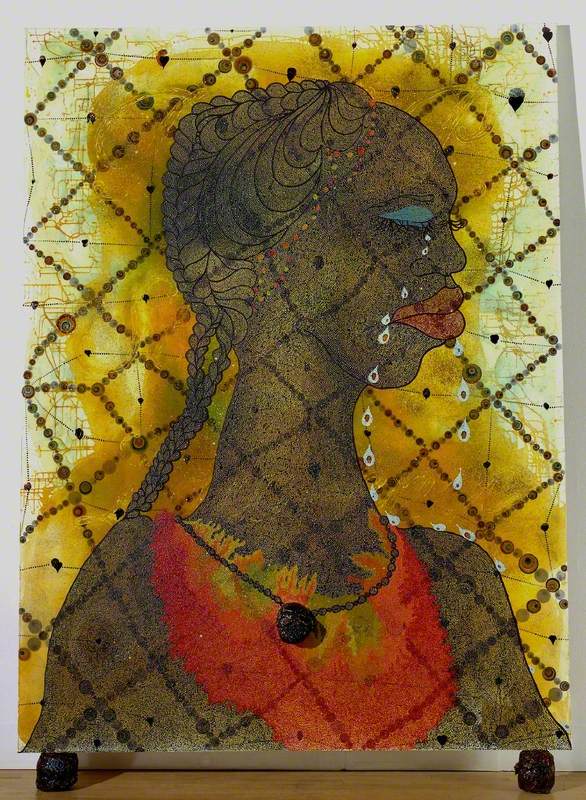

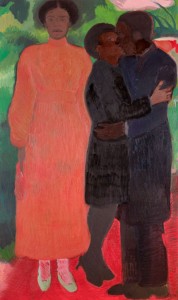

Whatever you say squidward

2021, acrylic, wool, human hair, kanekalon hair on hessian by Anya Paintsil (b.1993)

My most recent work, Whatever you say squidward, depicts my sister and me. It makes me laugh every time I look at it. I think the fact that it is in textile form makes it funnier. I'm glad that humour is there, because it relates to a darker time in my childhood. It's about getting our power back as children; we used humour as a weapon and to fight back.

Lydia: The titles of your work are often in Welsh. Can you tell us more about the decision to keep your titles in this language?

Anya: Some of my works are titled in Welsh because they are based on nostalgia and childhood memories. They relate specifically to my experiences of growing up in Wales.

The first piece of work I titled in Welsh was 'Ni yn unig' which translates to 'Only us' in English. It depicts me and my sister on a background of complete whiteness with little flecks of pink and brown and exaggerated facial features. This work is about highlighting the experience of being mixed race in a very white environment. We always felt different and out of place.

Ni yn unig

2020, punch-needled acrylic, cotton & human hair on hessian by Anya Paintsil (b.1993)

The other works I titled in Welsh because they were heavily based on memory. For example, Mam, Mair a fi (2020), translates to 'Mum, Mair and me', as well as Mair at Cylch Meithrin which translates into 'Mair at nursery circle'. The figure is my sister crying at nursery school holding her toy duck, 'Floppy'. I'm drawing from a point in my life when I would speak Welsh every day. A lot of my work is heavily based on old photography, especially the facial expressions and poses.

I like combining the Welsh language with my figures, who are all people of colour. Until the age of 18 (when I left Wales), often people wouldn't believe me when I said I'm from Wales. They couldn't understand that a mixed-race person could be from that region.

Reclaiming the Welsh language in my work is a way to protect my Welsh identity because so many people throughout my life have questioned it. In their minds, Welshness is homogenously white, but in reality, Wales has one of the oldest Black communities in Europe. For example, in Butetown (commonly known as 'Tiger Bay') in Cardiff, there is a large British-born Somali community, which has been there since the nineteenth century.

Lydia: Do you have any studio rituals?

Anya: In the morning I don't like to speak to anyone. This is probably to do with having autism – if anyone is in my personal space in the morning I feel angry. I need to be alone. I don't drink coffee, only tea. I'll go to my studio (which is currently the spare bedroom) and have breakfast there while I start working. I usually work until 2 or 3 in the morning.

Lydia: What advice would you give to aspiring artists?

Anya: Do what you want to do. Don't procrastinate (that's my main challenge).

Because of being autistic, one of my biggest difficulties is speaking in front of people, especially because my work is so personal. By now, I'm quite adept at masking my autism so people don't necessarily realise that I'm not neurotypical. But I've had to practise a lot and write things down to get to a place where I can talk confidently about my work. So that would also be my advice: don't be scared to show people your work, and if you find it hard to communicate, then practise until you develop that confidence.

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

Anya Paintsil is represented by Ed Cross Fine Art and her solo show is currently on at Glynn Vivian, Swansea until 31st October 2021

She is also featured in the exhibition, 'Bold Black British' at Christie's and has work included in 'Maker's Eye: Stories of Craft' at the Craft Council Gallery, London until 9th October and 'Hapticity: A Theory of Touch and Identity', at Lychee One, London until 30th October 2021