In the series 'Seven questions with...' Art UK speaks to some of the most exciting emerging and established artists working today.

Working in a range of media, from embossed works on paper to painting and large-scale wall drawings, Barbara Walker seeks to counter racially skewed narratives and establish alternative readings of the past. Her distinctive figurative works, informed by the social and political realities that affect her and others in Black communities, explore issues of power, race, representation and belonging.

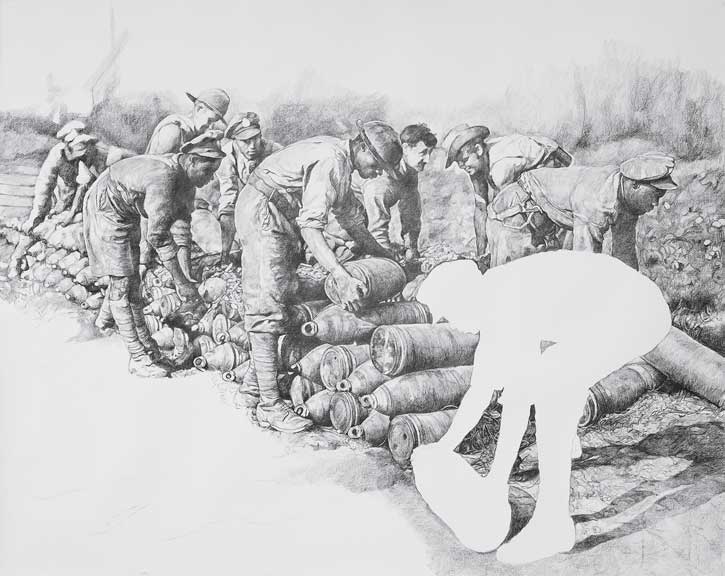

Grounding her practice in extensive periods of research, the Birmingham-based artist scours public archives and collections to identify overlooked histories. Her series 'Shock and Awe' (2015–ongoing), for instance, examines the contribution of Caribbean servicemen and women serving in the British Army from 1914 to the present day – people barely acknowledged in the public record, but who are monumentalised in her delicate graphite drawings and large-scale charcoal works.

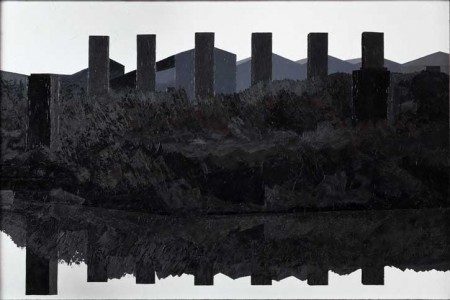

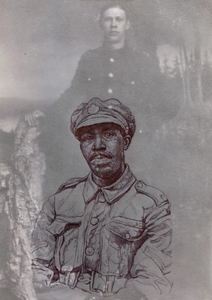

The Big Secret I (from 'Shock and Awe')

2015, Conté on paper by Barbara Walker (b.1964)

Walker's exhibition at Cristea Roberts Gallery, 'Barbara Walker: Vanishing Point', interrogates the Black presence in Western art history, focussing on the way that institutions and the dominant culture perpetuate negative attitudes and perceptions. Reinterpreting works by Paolo Veronese, Daniel Vertangen, Pierre Mignard, and others, she uses a combination of drawing and blind embossing to highlight Black figures while obscuring the dominant white subjects. With these acts of erasure, Walker spotlights historical inequities and invites viewers to consider how history is made and how such strategies might reorient our understanding of Black identity.

Installation view of 'Barbara Walker: Vanishing Point' at Cristea Roberts Gallery, London, 2022

David Trigg: How did the 'Vanishing Point' series get started?

Barbara Walker: One of my favourite places to see art is The National Gallery in London. By engaging with that space, I started noticing the front-of-house staff of colour and began having dialogues with them about what they identified with. One led me to Jan Gossaert's The Adoration of the Kings. That work is magnificent. You can see from the Black king's physiognomy that he is painted from life, not from imagination.

In Renaissance Europe, there were lots of Black people who were generally either enslaved people, servants or both. With that in mind, I looked at the Old Masters to see how the Black subject is represented within the Western canon. A lot of portraits depict wealthy patrons: landowners, merchants, royalty. The poorer you were, the less important you were, and if you were Black, you certainly weren't important. So the gallery, through the values communicated by these paintings, is telling us who is important and who isn't. That had consequences in the past which are still being felt today in terms of how Black communities are represented and viewed.

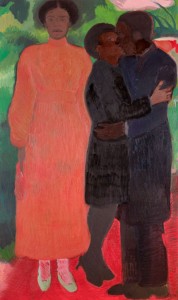

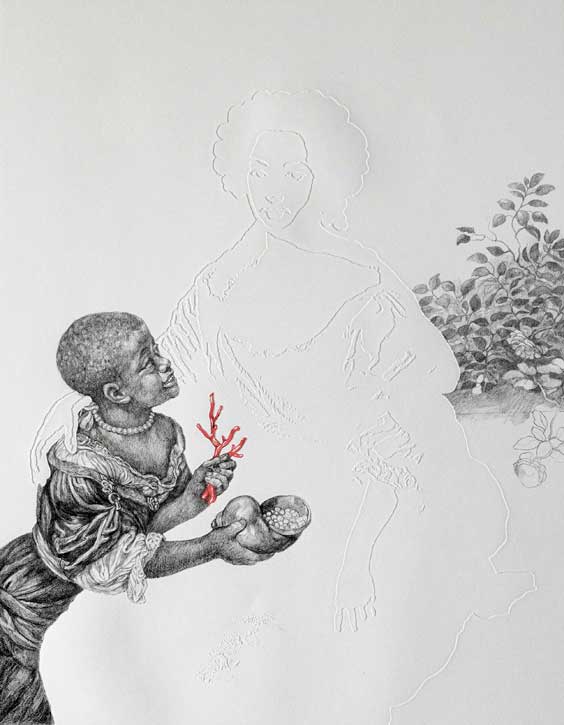

Vanishing Point 24 (Mignard)

2021, graphite on embossed Somerset satin paper by Barbara Walker (b.1964)

The girl with the coral in Vanishing Point 24 (Mignard) (2021) is enslaved, and the woman in the centre is Louise de Kéroualle, Charles II's mistress, from a Mignard painting in the National Portrait Gallery. The girl is a possession, but she's got this stoic look. It's emotionally and psychologically disturbing, but as I draw, I imagine that I'm extracting and saving her.

Louise de Kéroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth

1682

Pierre Mignard I (1612–1695)

A lot of viewers don't even see the Black figures in the original paintings. The conversations are about perspective, composition, colour, but the Black figure is rarely discussed. I find that problematic. 'Vanishing Point' asks, how do we move on from this. In the wake of Black Lives Matter, there is now a conversation, but I'm hoping it's not just a novelty and is sustained.

David: What is the function of erasure in your work?

Barbara: I'm very interested in visibility and non-visibility in terms of marginalised communities. I use erasure as a metaphor for how the Black community is overlooked, ignored, and even dehumanised by society.

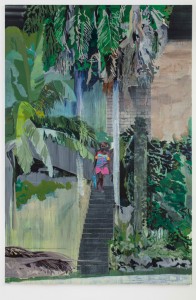

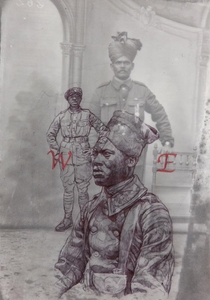

Marking the Moment 1

2022, graphite on paper overlaid with mylar by Barbara Walker (b.1964)

In previous works you see me wash away, cut out, isolate or diminish certain aspects of an image and bring others to the forefront. In the 'Vanishing Point' drawings, embossing achieves that erasure. You'll see that the Black figures often appear in the corner, or on the side, and to an extent that's how I feel in society. However, I don't want to be seen as a victim because these figures are not victims. When I represent them, they're standing strong, hence why they are large. It's about empowering them.

David: Archival research plays a large role in your practice. What attracts you to this way of working?

Barbara: I'm interested in history and how it informs the present. I'll go into archives looking for the backstories behind events, individuals or paintings, but I never know what I'm going to find. Making art is about curiosity and it's the same in the archive – I love playing in the unknown. Sometimes, when I'm flicking through materials, I'll find a nugget that inspires me and then I run with it. It could be a gem of information that I wasn't aware of, a statement, a colour, or even the feel of old paper. Sometimes I hit a brick wall and need to start again, but that's all part of the adventure.

David: I Was There IV (2019), from your 'Shock and Awe' series is a portrait of a young Black soldier made on tracing paper and laid over a photograph of a white soldier. How did this work come about?

Barbara: Both images are of British soldiers from the First World War; they were probably the same age, about 19 or 20. The images are from vintage postcards that I found on eBay. The overlay is again about erasure; I wanted to push the white figure to the background and bring the Black figure to the foreground. At school I learned that this was a white man's war, but actually several thousand people from the Caribbean came and fought.

I researched the British West Indies Regiment in the Imperial War Museum. I wanted to unpack that story because it's not generally known. These soldiers wanted to be equal and support the mother country. In the beginning, a lot of them were denied the right to fight and relegated to the labour force. With so many fatalities, Lord Kitchener eventually brought them in, and when they did fight, they fought valiantly! But those stories are never told.

Even now, the army relies on Commonwealth countries. Vron Ware's book Military Migrants: Fighting for YOUR Country (Migration, Diasporas and Citizenship) was very helpful to me and she directed me to a few individuals whose portraits I drew on First World War recruitment posters, so you have past and present together. I interviewed them and took photos of them. I wanted to meet them because I wanted that experience to filter into the drawings.

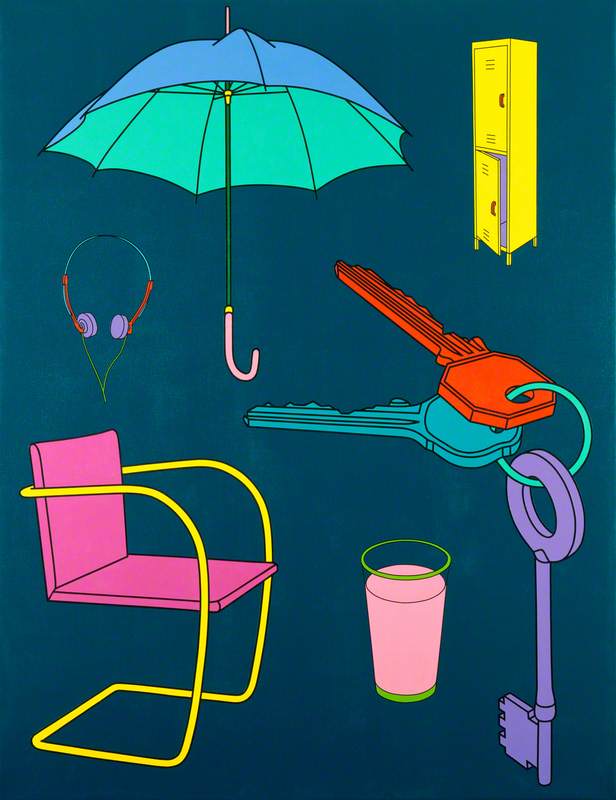

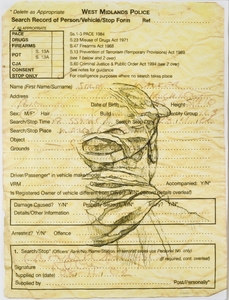

I Can Paint a Picture with a Pin, 2006

1984

Barbara Walker

David: I think it does, much like your 'I can Paint a Picture With a Pin' series (2006), in which portraits of your son are drawn on top of prints of police Stop and Search forms. How did it feel to make such a personal series of drawings?

Barbara: It was quite emotional. Solomon is my youngest son and I remember when he was first stopped and searched like it was yesterday. I felt helpless, because as a parent you're there to protect your children, and I couldn't do anything to stop it. He felt really disrespected and embarrassed, and for me, it was the thought of him being dehumanised. He was really angry and I was too. I channelled that anger into the work; my emotions are very much embedded in those drawings.

I see the search record as a kind of drawing done by the police officer, which is why I wanted to draw on it, to introduce the mother's hand. I scan them because the originals are very delicate and crumpled; as you can imagine, in his frustration he screwed them up and put them in his pocket. You can see all of that tension in the works. They are portraits but also collaborations between my son and myself.

'Broken Angel' at Coventry Cathedral, 2022

David: Your recent installation for Coventry Cathedral's 'Broken Angel' project replaces a section of John Hutton's great glass West Screen, which was vandalised in 2020, with drawings of everyday objects. How did you approach the commission?

Barbara: The commission came during the pandemic. I hadn't seen my children or grandchildren for a while because I was self-isolating. I wanted to respond directly to Hutton's window with its angels and saints, so I started to think about what a contemporary angel might be, and for me, it was my children and grandchildren – playing on the word 'angel' as a term of affection.

Hutton's saints are holding objects they are associated with: a sword, a book, a bird. I began thinking about objects that we cling to today and asked my children to send me a picture of something important to them. One of my daughters is Muslim and she sent pictures of the Qur'an; one that was very worn and dog-eared. I asked her why it looked like that, and she said it was because it's actually used, so we went with it. My eldest daughter wears bracelets that I gave her and some of the saints also wear bracelets. The teddy bear is my son's and the skateboard is my grandson's. I asked him why he suggested it and he said 'Nana, when I'm on my skateboard I feel free', so it's about freedom and feeling happy.

Barbara Walker, 2022

David: What advice would you give to aspiring artists?

Barbara: Don't take no for an answer. Do what makes you happy, believe in yourself and create the art that you want to make. Have integrity and then the rest will come.

David Trigg, writer, critic and art historian

'Barbara Walker: Vanishing Point' at Cristea Roberts Gallery runs until 23rd April 2022

Walker's 'Broken Angel' commission is at Coventry Cathedral until 12th June 2022