In the series 'Seven questions with...' Art UK speaks to some of the most exciting emerging and established artists working today.

For over four decades, London-based artist Chila Kumari Singh Burman has been creating a kaleidoscopic, multidisciplinary art practice that can only be described as her own. Born in Liverpool to Punjabi parents who moved to post-war Britain, she has been a significant figure in the Black British Art movement of the 1980s apart from creating her own visual vocabulary of play and politics in her art.

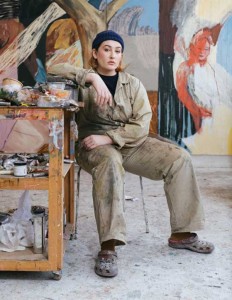

Chila with her 2020 installation 'Remembering a Brave New World' at Tate Britain

Her practice, which spans collage, painting, installations, printmaking, neons, video, performance art and pop culture, explores her British-Indian heritage and what she describes as 'the experiences and aesthetics of Asian femininity'. Under the vibrant colours, glitter and pop culture references that lace the work lies a playful subversive subtext of gender, politics, class, culture and identity.

I spoke to Chila about how identity and nostalgia feed her work, making art in turbulent times, and how her creative process has evolved over 40 years.

Rohini Kejriwal: You've been making art for four decades. How did it all begin for you?

Chila Kumari Singh Burman: Like most kiddies around the age of ten, I just always enjoyed art over other subjects. I didn't know if it was good or bad, I just liked it. We didn't have crayons or pencils around growing up, so I'd come back from school and go play in the streets with chalk, a ball or marbles. We had to make up our own games and remake stuff with the same toys. That's how I became quite creative. Maybe I was naturally gifted or talented. Maybe it's in my DNA because my Dad was a tailor and obviously had an eye for detail.

Chila with bindis

Rohini: How does your Indian diaspora identity play out in the work, which is a mix of pop culture, nostalgia, fantasy and storytelling?

Chila: That's very interesting how you've summarised those contrasts. Growing up, we had an ice cream van in front of the house with a tiger on top and nice patterns and shapes painted on it. When I was around 12, I was in a very academics-oriented grammar school. We didn't do much scribbling or painting and it was all a bit boring. That's probably what made my life more orderly.

I'd go home and get out of my uniform, speak in Punjabi and enter an Indian world. When I'd step out on the streets to play, it was again an English world. So school was very English, and home was very Indian. We'd have relatives over for dinners and make different subzis (Indian dishes) but dessert would be egg custard with cardamom. There was a lot of oral history from listening to the conversations at home. This was also the time my father was teaching other Indian families how to sell ice cream and shaping the ice cream trade in Liverpool.

Chila as a student at Leeds Polytechnic in 1979

In 1975, I went to Southport College of Art, which gave me a lot of confidence because I tried pretty much everything. My teachers suggested I go study Fine Art Printmaking at Leeds Polytechnic, which became a formative time for my practice. Those were the height of the punk and reggae days. There was performance art, film screenings, discussions of Marxism and feminism and graffiti everywhere. Leeds had a big Indian community and different art schools, and it was a real creative burst of energy and loads of visual stimulus around.

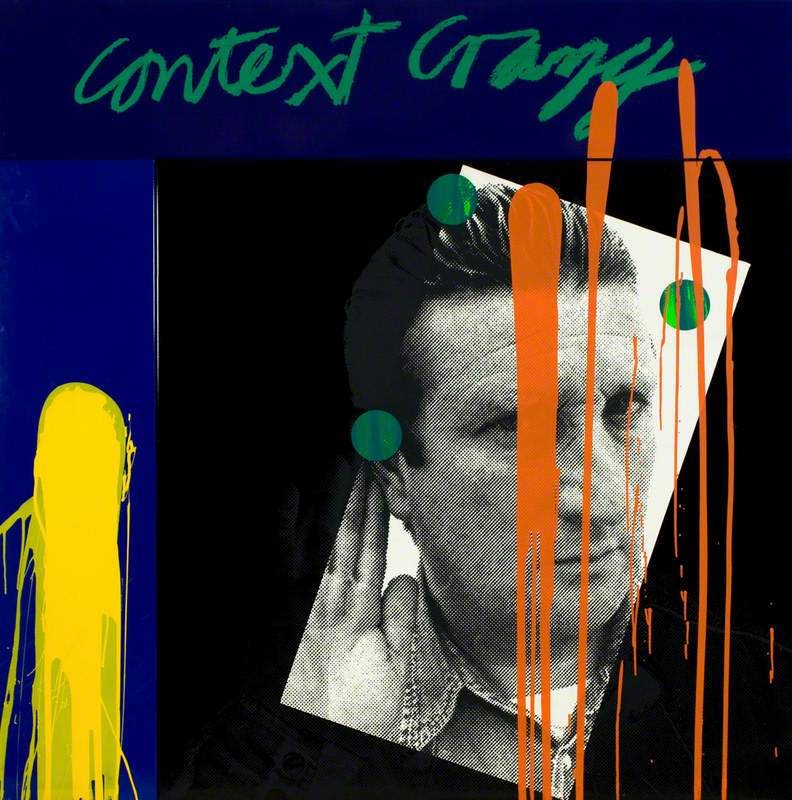

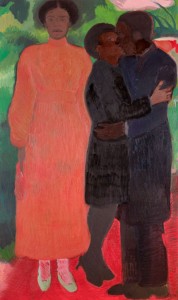

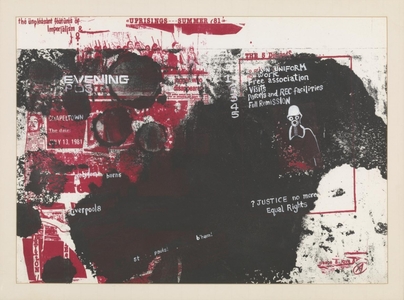

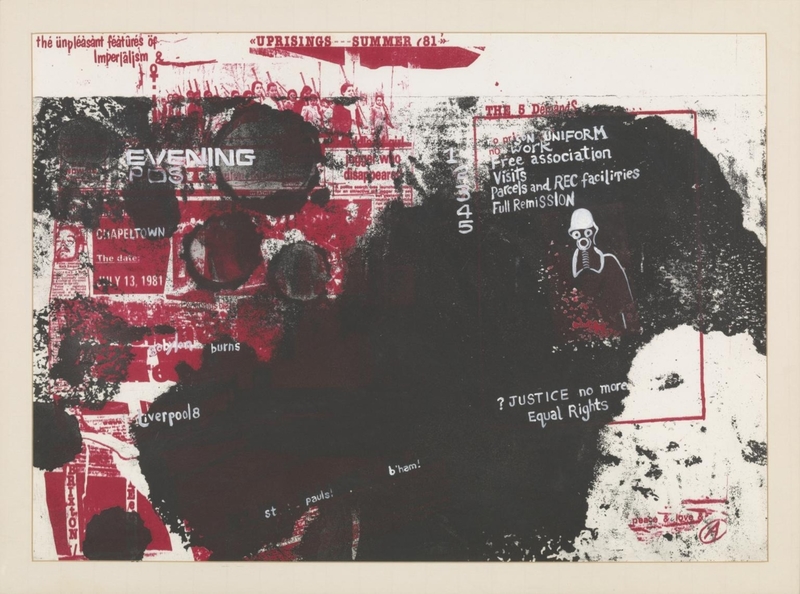

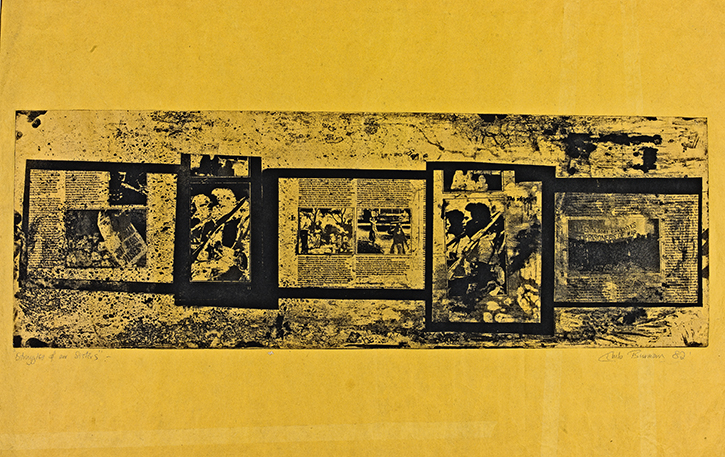

If There is No Struggle, There is No Progress - Uprisings

(Riot Series) 1981

Chila Kumari Singh Burman (b.1957)

Militant Women – Struggles of our Sisters

1983, artwork by Chila Kumari Singh Burman (b.1957)

I also spent three months in India before that with my cousins and when I went back to Leeds, my Indian identity became the forefront. It became ingrained, and I even changed my name from Shela to Chila. In the 1990s, my sister had eloped and my brothers were sent to boarding schools in India, so I was alone in the house and turned my bedroom into my art studio. That's where a lot of the personal works and series emerged. My current studio in Hackney is full of art supplies, bindis, jewellery and sequins. It's where all the magic happens!

Rohini: You've been someone who moves freely between mediums, often mashing them together to create your own techniques. Tell me about these experiments.

Chila: After Leeds, I went to the Slade School of Art in London, where I played with mediums like screenprinting, lithography and etching. Those were such layered and dense works because I'd combine techniques out of curiosity.

Etching

late 1970s/early 1980s, artwork by Chila Kumari Singh Burman (b.1957)

I loved etching. I'd dip the metal plates in a chemical bath and do screen printing on top of it, so there were holes and textures on them! As an artist, it was a bit like throwing everything into this melting pot and hoping something good would come out.

Cornet – Eat Me Now

2012, sculpture by Chila Kumari Singh Burman (b.1957)

I've also experimented with different 3D mediums over time, like the sculptural piece Eat Me Now in 2013, where I created a giant glittery ice cream cone with a chocolate flake on top. I've made glass ice creams and boobies, tried my hand at graffiti, and worked on murals.

In 2021, while working on the Tate facade, I was fed up with drawing all the time. So I'd just squirt loads of acrylic and oil paints on a piece of canvas and add spoons from the ice cream van, and those turned into what I call my Spoon Paintings. I believe it's always good to have something else going on because otherwise you can go a bit mad.

Spoon Painting

2021, artwork by Chila Kumari Singh Burman (b.1957)

Rohini: You've been obsessed with bindis (small dots worn on the forehead in India) in your work. How did that begin?

Chila: Growing up, when we'd go to the mandir (temple), I loved dressing up and putting on bindis. My cousins from India would send me packets and packets of bindis and body stickers. If anybody went to India – relatives, friends, girlfriends – I'd tell them to bring me back bindis. My studio has drawers full of them and I go through them super fast. There are fancy ones, plain black and red velvety ones, and more decorative ones. Colours and textures are forms of drawing, so I enjoy using bindis in my drawings.

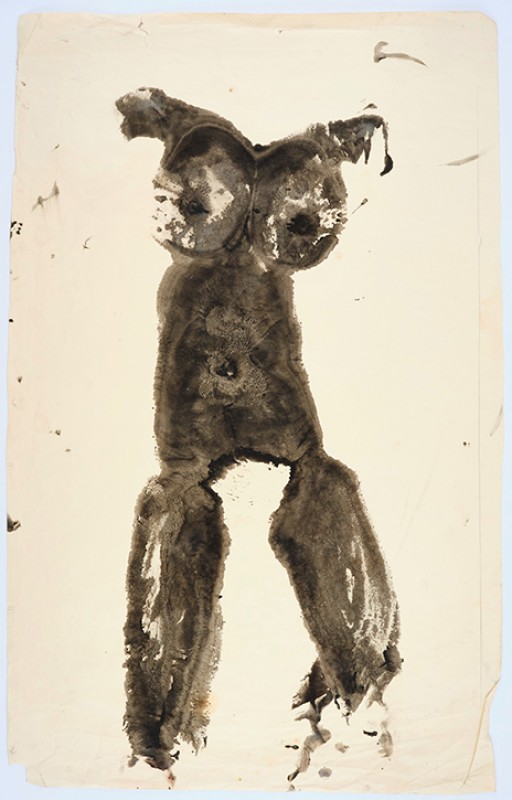

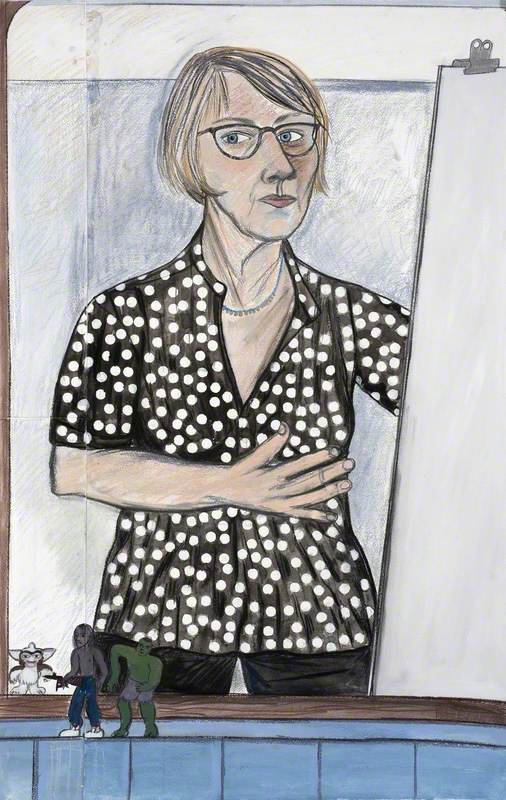

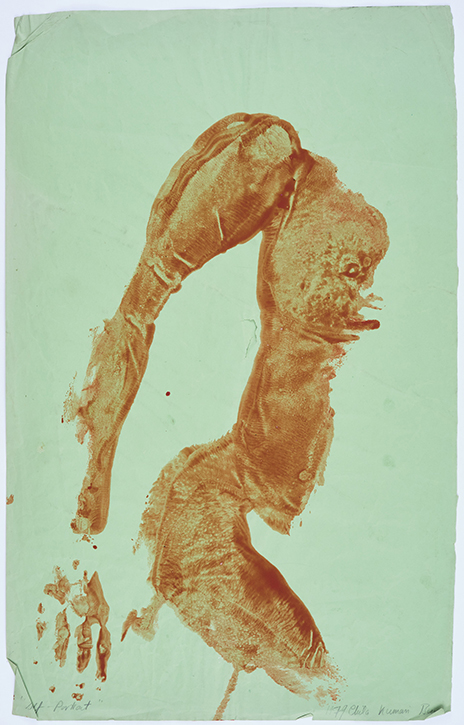

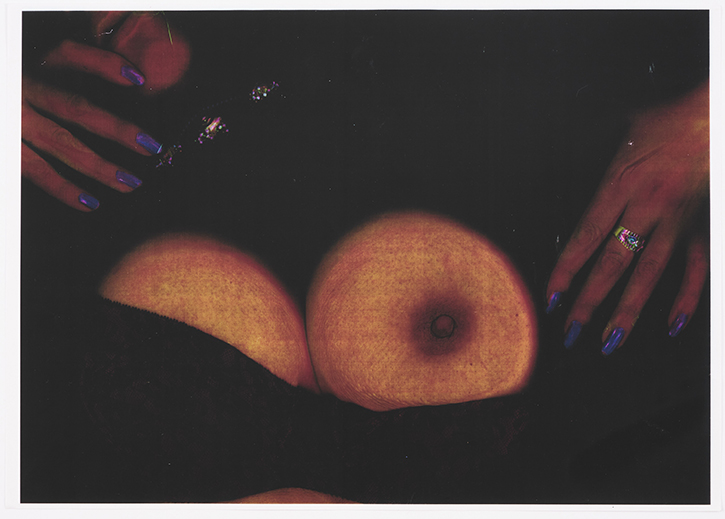

Body print

artwork by Chila Kumari Singh Burman (b.1957)

In the 1970s, I was introduced to Yves Klein's body prints and started doing body print experiments as well. During the International Workshop in Modinagar, India in the mid-1990s, I found a lot of cheap bindis there and started experimenting with body prints in my bedroom using bindis and thick khadi paper. I put the tadpole-shaped ones on my fanny because when you have an orgasm, it's all kind of moving down there, right? I put them all over: on my fanny, my titties, my face, and that series sparked a new love for bindis.

Body print

artwork by Chila Kumari Singh Burman (b.1957)

Rohini: Let's forward a little bit and talk about your more recent neon experiments.

Chila: The neons came about because, in 2020, the director of Tate Britain Alex Farquharson sent me an email out of the blue and invited me to do the Tate Winter Commission. I could not believe it but I agreed! This was March 2020, when COVID-19 took over our lives.

I was given an architectural drawing of the Tate facade and started filling it with textures and forms. Since we were all going into some darkness, I thought we had to come out of the dark tunnel with some light. I had visited God's Own Junkyard in Walthamstow years ago, with millions of glass neons by the late artist Chris Bracey. I knew I needed a material that's cheaper than glass neon and was told by an artist friend that neons are now made from silicone and can bend and give out illumination. So off we went from there!

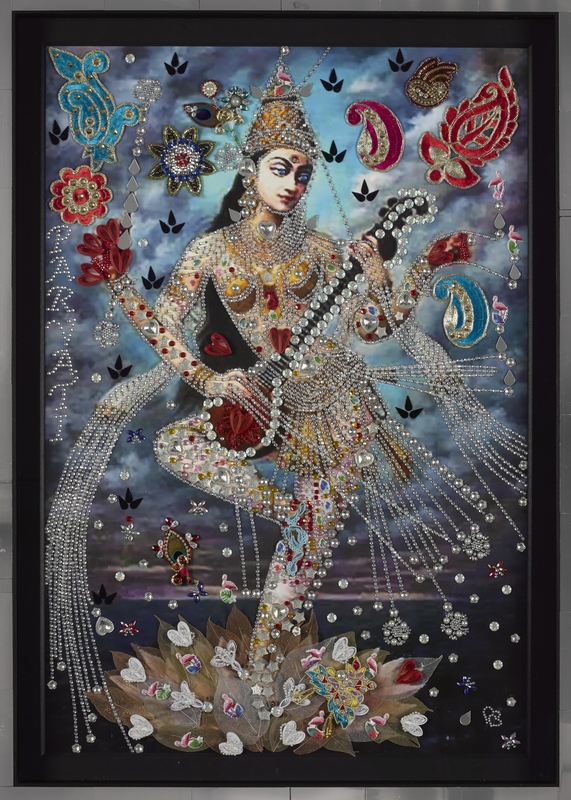

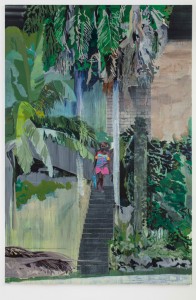

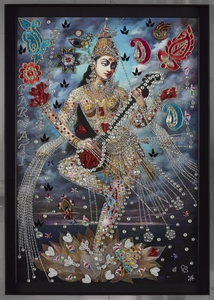

Remembering a Brave New World

2020, installation by Chila Kumari Singh Burman (b.1957) at Tate Britain

The title of the installation was Remembering A Brave New World, taken from Aldous Huxley's book because the work stands for remembering the victories of the past as we enter the brave new world. The Tate wanted it ready in November, which happened to be Diwali, the Festival of Lights. I wanted imagery of dynamic women who look really energetic and powerful. So I put Indian goddesses like Lakshmi and feminist icons like Lakshmi Bai/Jhansi Ki Rani, who once ruled the princely state of Jhansi, to stand for the awful things the British did in India.

Remembering a Brave New World

2020, installation by Chila Kumari Singh Burman (b.1957) at Tate Britain

The neoclassical architecture has its own historical connotations, and I covered the statue of Britannia with the strong and scary goddess Kali with a really long tongue. I put myself there too because I'm a brown belt in martial arts, and the form represents strength and power.

Remembering a Brave New World

2020, installation by Chila Kumari Singh Burman (b.1957) at Tate Britain

I added my Dad's ice cream van and the tiger, which was on top of his ice cream van. And words like 'We are here because you were there' as a nod to the British invasion of India, and 'I'm a mess' to throw light on the collective mess we were in. I also experimented with a collage-like technique on the pillars, where I repeatedly put the words 'Punjabi Rockers' almost like a wallpaper. Finally, on the triangle on top, I put words like 'Love', 'Dream', 'Joy' and 'Light'.

Remembering a Brave New World

2020, installation by Chila Kumari Singh Burman (b.1957) at Tate Britain

It became such a beacon of light! Every evening, there'd be over 300 people in the freezing cold, saying the colours and light made them feel warm. It honestly felt like a pilgrimage. Everyone was hanging out, dancing and drinking! People were having Tinder dates and parties and Tate left it on all night. It was also joyful during the day, especially for children. I met people from all over the world on those steps. I don't think I even realised what I'd done. I'd just stand and wonder where all these people came from.

Remembering a Brave New World

2020, installation by Chila Kumari Singh Burman (b.1957) at Tate Britain

Rohini: What have you been working on since the Tate commission?

Chila: I was commissioned to do a lot more neon works after Tate. In 2021, I worked on Fierceness in Scarcity, a tiger artwork incorporating inkjet, screen-printing and hand-cut collaged elements for WWF's Art For Your World campaign. I also did the Netflix car for the film White Tiger.

Do You See Words in Rainbows

2021, installation by Chila Kumari Singh Burman (b.1957) at Covent Garden

I created Do You See Words in Rainbows in Covent Garden's historic former vegetable market and spoke of my experiences as a South Asian woman, and did a similar neon installation called Liverpool Love of my Life on the Liverpool Town Hall. I also covered the Grundy Art Gallery in Blackpool with my neon installation Blackpool Light of My Life.

Liverpool Love of My Life

2021, installation by Chila Kumari Singh Burman (b.1957) at Liverpool Town Hall

During the Tate show, I worked on some merchandise like t-shirts, notebooks and what I call 'baby neons' for the Tate Modern shop. Tate Publishing contacted me afterwards and said they'd love to do a big fat book on me, so that's what I've been working on with different writers and contributors! It's a book on 40 years of my work and should be ready by September 2023. This year, I'm also making a Mars installation outside London's Science Museum, and going to Barcelona and Italy for different light festivals.

Blackpool Light of my Life

2021, installation by Chila Kumari Singh Burman (b.1957) at Grundy Art Gallery

Rohini: As a woman artist of South Asian origin in the UK, what challenges have you had to overcome over time?

Chila: Well, we're dealing with climate change, politics, the pandemic and so many troubling issues all around the world. So I try to unpack some of that in my work though I wouldn't say my work is issue-based. Still, we have to talk about what's happening and address realities… Like how more male works are being collected and South Asian art has been sidelined. We're being left behind, and I'm trying to get a show off the ground with South Asian artists.

Chila with her tiger artwork

I'm also working on getting a blue chip gallery to represent me because it's too much to do it all by myself. These last 18 months have transformed my life dramatically, and because I'm well known now and seen as someone who's made it, I'm being invited every week to do something somewhere. And there's a lot of professional jealousy, which is really sad because as South Asian women artists, everybody has to pull the weight and it's not happening enough. We need to talk about what's really going on because these are turbulent times and we're all in this together!

Rohini Kejriwal, writer, artist and art director