In the series 'Seven questions with...' Art UK speaks to some of the most exciting emerging and established artists working today.

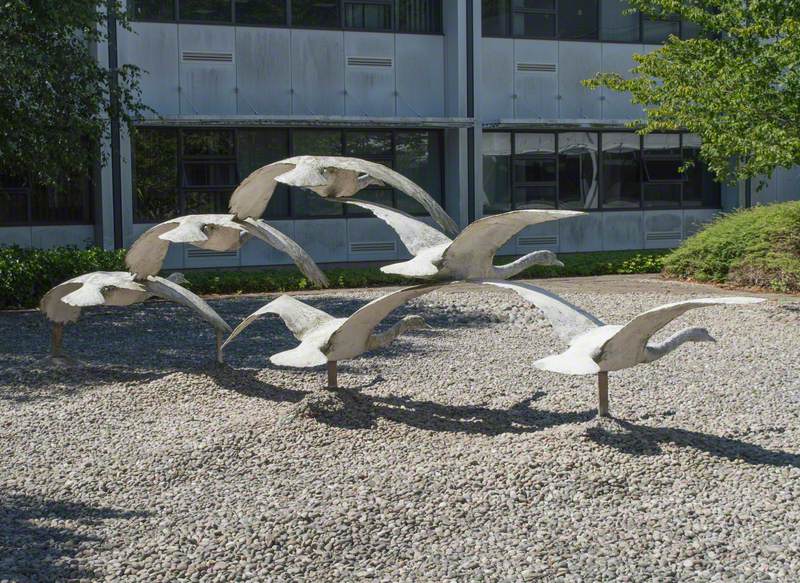

David Annand is one of the most prolific sculptors working in Britain today with over 67 sculptures on Art UK and counting. Following a commissioning process for a new sculpture in the Tillydrone area of Aberdeen, which was supported by Art UK's Sculpture Around You project, Annand's idea was chosen by a landslide public vote. In September 2022, the series of four origami-inspired swans were finally unveiled to the community. I caught up with Annand shortly after to reflect on this commission and his long career in sculpture.

Tillydrone Gateway Swans (Diamond Bridge)

David Annand

Shane Strachan, Art UK: On your website, you quote Scottish poet William Soutar who stated that 'Until the interest of an artist shifts from the personal sensation to a sense of communal service his work cannot grow. As pure artist his work may be technically more perfect in the exploitation of the ego – but it cannot take on real greatness until it bears the burden of a people.' How does this reflect your own development as an artist?

David Annand: I've used that quote ever since I found it back in the late 1980s in his book, Diaries of a Dying Man. He came from a district in Perth called Craigie. He went to the primary school there and then to Perth Academy, both of which I attended.

In terms of personal sensation and ego, I did do the odd personal work myself for galleries and things, but – have you ever heard of the Artybollocks Generator? Well, that's the sort of stuff that they would put up next to my work, and you wonder how actually genuine that sort of writing is. All of that was beginning to start when I was at college. This is the early seventies when it came in, and some of the people who laughed at it said they're 'mouth artists', not painters or sculptors or designers. They're just mouth artists.

Soutar did influence me a lot and that quote proved to be a useful mantra in relation to getting commissions as it just puts, in a nutshell, the fact you were going to listen to people in communities and take on what they had to say, if it was valuable – you do get a lot of waffle and outlandish ideas that wouldn't work in terms of structural engineering or health and safety. One thing about the quote though – it says until it bears the burden of a people. Well, it doesn't really feel like a burden for me.

Tillydrone Gateway Swans (Diamond Bridge)

David Annand

Shane: The swans sculpture in Aberdeen is one of many animal sculptures you've done across your prolific career, including of birds and even of swans in flight.

How does this one differ from those before it? And how did the community of Tillydrone feed into its development?

David: Well, it was to do with the history of Tillydrone. It used to have all these paper mills along the banks that the River Don polluting it, you know, and the quality of wildlife in the river went seriously downhill. Now the paper mills have all long gone and there's virtually no trace of them apart from the odd bit of industrial machinery kicking about, the swans have come back in force on the Don. And so it's a no-brainer that it combines swans and paper into origami paper swans.

Tillydrone Gateway Swans (Diamond Bridge)

David Annand

They're reinvented slightly however in that these paper swans are in flight and a little more lifelike than you could do with paper. If you follow the actual rules of origami, it should only be one piece of square paper, but kirigami is a different variation on it, which is when you're allowed to cut the paper. Even so, the sort of quality of cutting paper the Japanese do is just so wonderful, but of course I was working with very chunky stainless steel, far heavier than we thought it might be in order to be structurally sound.

Shane: The Tillydrone sculpture was actually referred to as a 'Gateway Feature' throughout the commissioning process. It was also pitched as somewhat of a traffic calming measure, reminding drivers they were entering a community. As an artist, how do you feel about sculpture having these additional purposes?

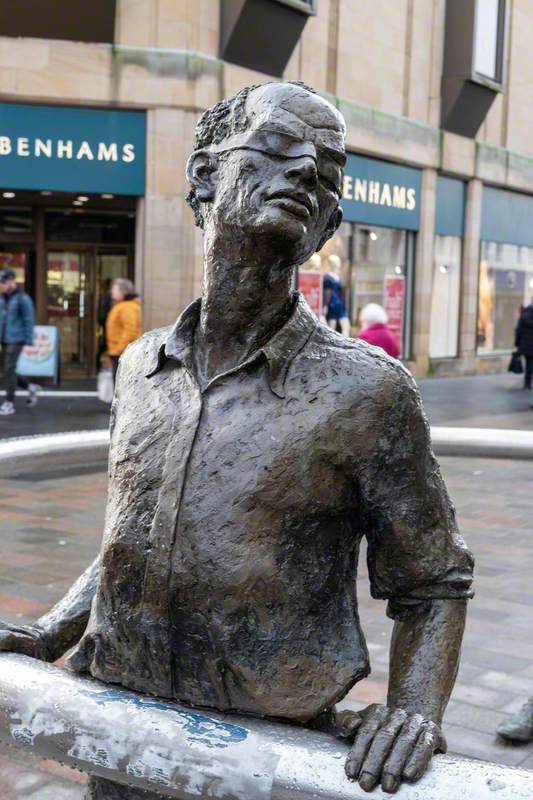

David: I have a different sculpture which takes its title from a Soutar poem, Nae Day Sae Dark, and that's both street furniture and art, and a lot of my sculptures are.

One that I did with Seamus Heaney in the Marie Curie Hospice in Belfast is garden furniture and art, so people can sit on it and it's primarily for terminally ill patients and they can sit there and apparently some actually talk to the sculpture of the lady on the bench which Heaney's poem welcomes them to do.

Similarly in Mansfield, I did a sculpture called Amphitheatre and the playwright and poet Ken Fagan wrote a nice little verse inviting people to come inside the sculpture and have a seat, and also get up and take a turn to perform in it.

Apparently, it does get used for that now and then, mainly by drunk people, but if that's the case, that's great, you know. Obviously at the end of projects, it's like, 'Now this is yours. It's not mine. It's yours now and do what you like with it.'

Shane: The swans are also an example of several of your public works which involve sculptures being displayed atop poles or high structures, playing with gravity, such as Reel of Three and The Night Watch Jugglers. What does this element of height add to these works?

David: As well as playing with physics and gravity, one of the reasons is to put them out of the way for specific reasons. There's this one in London called Civic Pride. It's a group of one lion and three lionesses, and they're all at strategic points at a very busy junction. I made the pillars so that they're on the same eye level as the signage. That also meant that part of the sculpture was see-through so that people could check for oncoming traffic.

From a practical point of view, sometimes you want to keep them out of reach of damage. I made a bigger version of Nae Day Sae Dark in Kilwinning and I actually had to spend some time this summer repairing it because it's bronze resin and some local youths spent quite a bit of energy smashing them up with hammers!

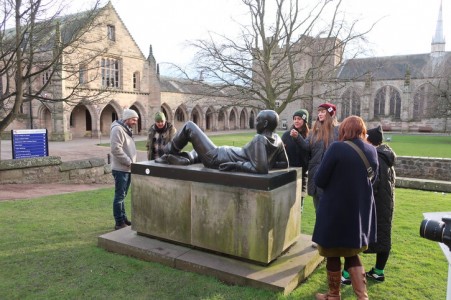

On the other hand, when I can, I try to do away with plinths, especially if they are figures of famous people – I try to get them on the ground if that's what's needed. Occasionally the sculpture might be of a person that's almost being deified, or from so long ago, that they should be on a plinth, like Henry Wardlaw of St Andrews who was the founder of the university in the 1400s. He was a bishop dressed in full regalia, so we needed him on a plinth as it's rather apt that way.

We're delighted to announce that the new Wardlaw Museum will open on Saturday 4th April 2020! Bishop Wardlaw founded the @univofstandrews over 600 years ago — a groundbreaking act that changed the place of St Andrews. This statue stands proudly in St Mary's Quad. #Wardlaw2020 pic.twitter.com/i2Y2i92G1C

— Museums of the University of St Andrews (@MuseumsUniStA) February 25, 2020

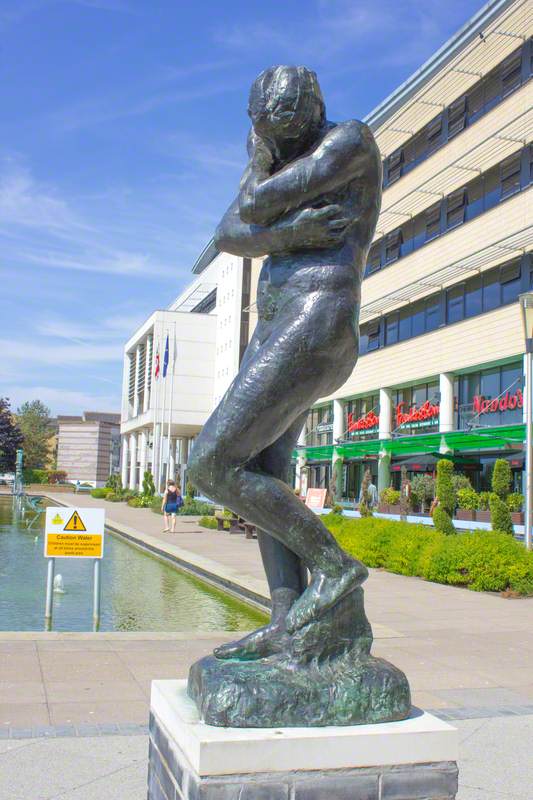

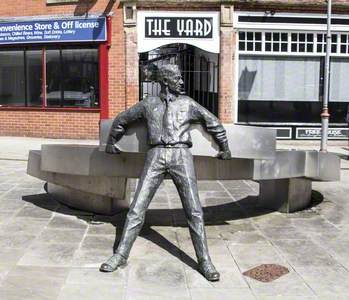

But my sculpture of the writer Robert Fergusson became very popular in Edinburgh because he's at ground level and you can't go past him now without seeing someone taking a selfie with him. You can't do that with other statues on the Royal Mile because they're all on huge plinths.

Robert Fergusson (1750–1774)

2004

David Annand, Powderhall Bronze

Shane: As a writer myself, I find it fascinating how many poets have written poems in response to your sculptures, including Seamus Heaney and Edwin Morgan. What do you feel is the relationship between sculpture and poetry in your work?

David: It goes back to that sculpture with Soutar's poetry in the title – Nae Day Sae Dark in Perth. I actually had the idea for the sculpture before I found the poem to fit it. The sculpture grew around that, you know?

One of the figures has got a blindfold on and one of the reasons I did that was because I was good at doing eyes. When I sculpt eyes, they talk straight back to you, or they look straight back at you. And well, I was quite amused by The Who smashing up their guitars so that they were defying what they were best at. So I thought, 'I'll put a mask on the guy's eyes,' which also makes him look lost. And it's also a sculptural reference to darkness because you can't really sculpt darkness.

So after using poetry to inspire that piece, I started commissioning poets because it's added value. I would sometimes get stuff back from them even I didn't understand but I still used it because it had a mystery to it. There's a country and western song I like – I forget who wrote it – but it says, let the mystery be about the meaning of life and all that stuff. If you don't understand it, let the mystery be. [Ed. – it was Iris DeMent]

A lot of people go past some sculpture and they might just look at it once. However, they may be more comfortable with the written word than they are with what they might perceive as three-dimensional nonsense. The classic is, every time, somebody goes past when we're installing something – and it happened in Tillydrone – you get people shouting out 'Waste of f*cking money'. And we shout back, 'So was your education' – carefully though, so they don't hear it!

But you know, I understand that as well, because very early on in my career, I was installing a similar piece in Wrexham and then this woman came up to me in tears saying, 'What is this? You're making this and the school roof's leaking onto my daughter's jotters when she's working.' And she was just sobbing. And I said, 'Well, I sympathise but, you know, this is also a job for me.' And she was very nice to me. She didn't take it out on me. I think she was going to take it out on a councillor.

Shane: When I look through the works on Art UK, I see that you've sculpted a lot of figures and busts of men and only a handful of women. How do you feel about this commissioning imbalance from an artist's perspective?

David: Yes, that has been the case, particularly in the past. I have tried to right the wrong by sculpting more women, although they're mainly fictional or anonymous figures.

For instance, one of the more recent sculptures I did that's now in the A&E department in Limerick, it's a healthcare worker, like a medic basically, sitting on a bench in the middle of the hospital with a nice poem on it, and a wee dog looking at her. The other one I mentioned in the hospice in Belfast, she's not meant to be a healthcare worker or anything. She's just sitting there being friendly and welcoming, like a big sister.

In terms of historical figures, I did a sculpture of Jackie Crookstone, who fought against compulsory conscription during the Napoleonic Wars in Tranent and was killed in the resulting riots.

And then more recently, I did Mary Queen of Scots. She's on a huge plinth, which is very appropriate for the actual setting because it's Linlithgow Palace. Historic Environment Scotland were very good – they actually used it as a training exercise for an apprentice to carve the stones and do the letter cutting.

Shane: I know this might be very hard to select, but do you have a favourite sculpture or two, whether that be because of the finished piece or how it came about?

David: I think it's the more simple ones, because that's the idea, you know. For Tillydrone, it's the hardest thing to do to get something that actually refers to the place and uniqueness – which in this case I chose the paper mills and the swans – that's been edited down like the way poets do. They edit it and edit it, and then you go back and edit it again. So you're trying to get the simplest idea.

The one in the Belfast hospice, it's called Still, because Seamus Heaney just played with the simplest of words, like in 'still yourself', meaning calm yourself, but also you're still alive, you're still here.

Heaney invited us and the hospice staff to include things. One of the hospice staff said, 'Take your time'. Heaney said that you can't really say that to people in a hospice because they don't have it, so he just took out the 'your' so it said, 'Take time'. Instead of trying to think of another word, he just took one out, and that's a mark of a real wordsmith that you use less, and it's also the mark of a good sculptor.

Shane Strachan, Art UK's Learning and Engagement Manager