In the series 'Seven questions with...' Art UK speaks to some of the most exciting emerging and established artists working today.

Allegorical, whimsical and sometimes mystical, the colourful figurative paintings of Eileen Cooper first came to prominence in the 1980s. Born in Glossop, Derbyshire, Cooper became an art school lecturer as well as a prolific visual artist working across painting, drawing, print, collage and ceramics. For over four decades she has taught part-time at a number of prestigious art schools: St Martin's, the Royal College of Art, City & Guilds in London and the Royal Academy of Arts.

In 2000, she was elected a Royal Academician, and from 2010 to 2017 she served as Keeper of the Royal Academy, becoming the first woman to be elected to this role since the RA began in 1768. 'Parallel Lines: Eileen Cooper and Leicester's Art Collection' is the first major survey of the British artist's career, assembling historic works from the collection as well as Cooper's earliest and most recent paintings, many of which centre on the female form. By displaying Cooper's works next to historic works from Leicester's collection, many of which are by women artists, the show offers a refreshing contrast of figurative styles.

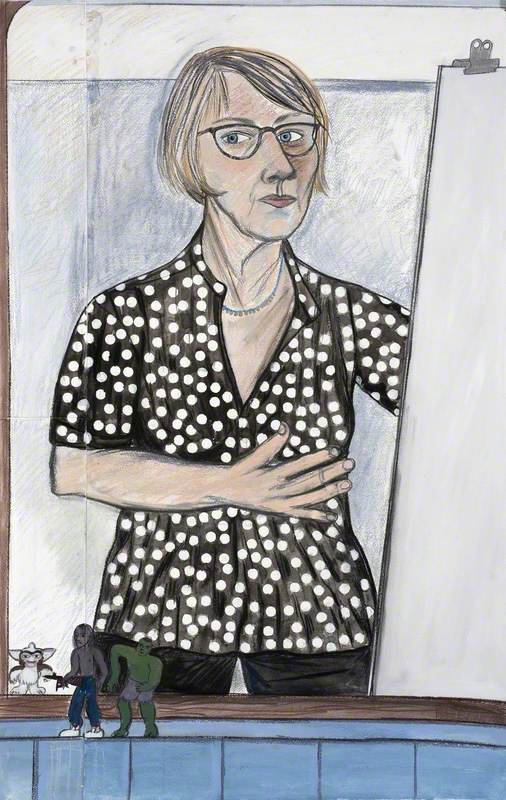

Installation view of 'Parallel Lines: Eileen Cooper and Leicester's Art Collection'

Lydia Figes, Art UK: 'Parallel Lines' draws parallels between your works with the paintings of other figurative artists found in Leicester's collection. How involved were you in the curatorial process of situating your work next to these artists – and did you feel you personally had a rapport with their work before the show?

Eileen Cooper: The concept of the exhibition was down to the curator Kathleen Soriano, though we had wanted to work together on a big project for a long time. We both had Leicester collection in our past because she had studied at Leicester and I had one of my first teaching jobs at Leicester Polytechnic in about 1980.

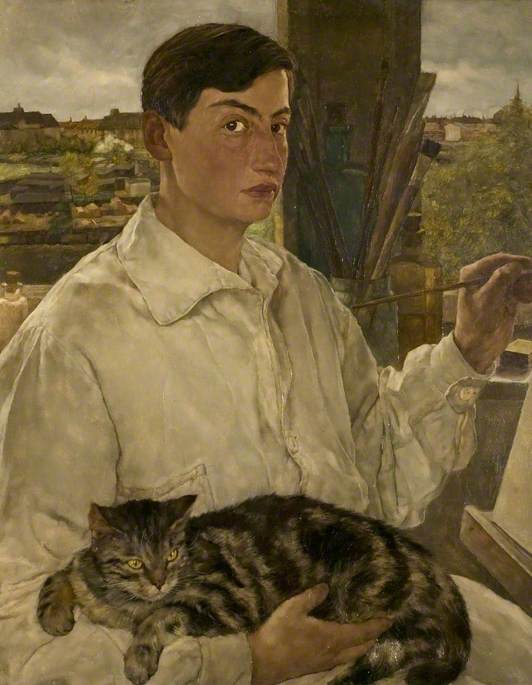

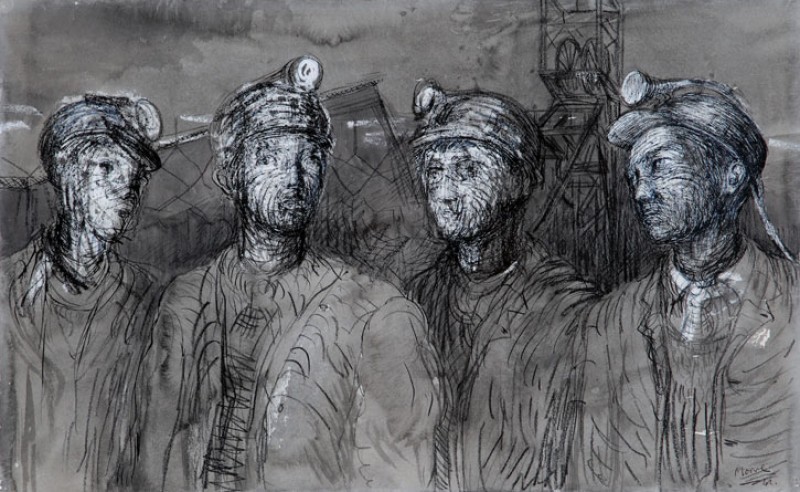

Kathleen saw correlations between major works in Leicester's collection with my work. For example, the works of German Expressionist artists, the paintings of Laura Knight, Therese Lessore, and the female self-portraits of Paula Modersohn-Becker and Lotte Laserstein. We both had an emotional connection to the collection from when we were much younger.

Lydia: 'Parallel Lines' brings together earlier works dating back to the 1980s, with paintings you have completed over the past few years. Although figurative painting has remained central to your practice, your style has changed quite a lot since then. What does it feel like to look back on work from over 4 decades ago and compare it with the work you are making today?

Eileen: It was incredibly emotional really. I find it shocking to see my work from the '80s next to the recent work. My work has an autobiographical element and is closely linked to what I went through in my life. Now I'm approaching the age of 70, so there is a lot to look back on – looking back is a strange business.

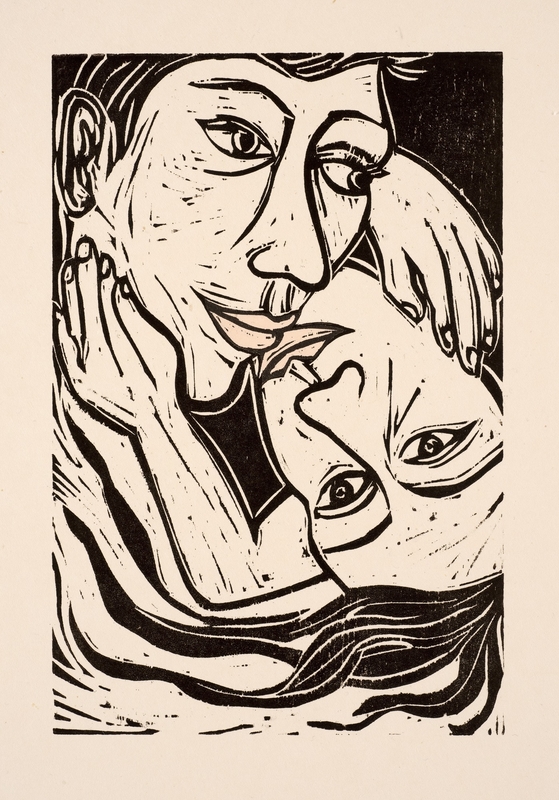

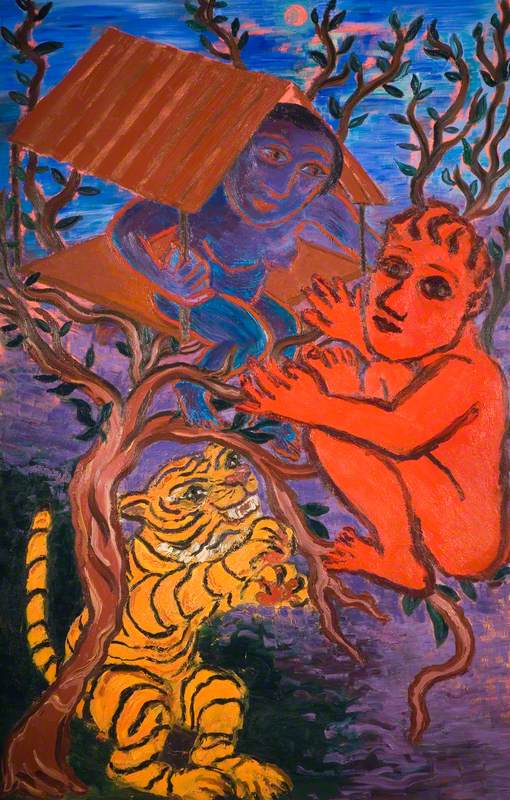

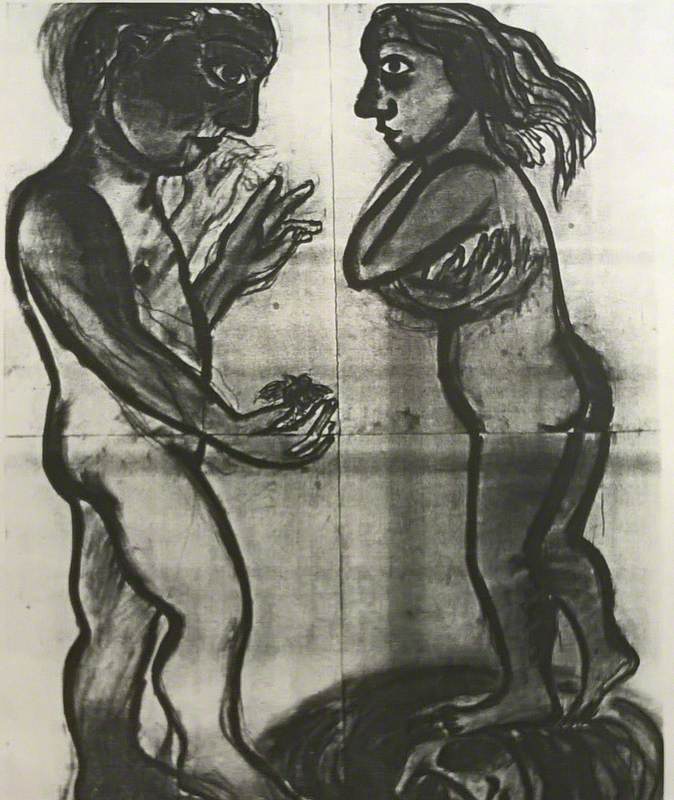

A lot of the works date to the time when I had children, when creativity became very linked to fertility and the theme of nurturing underpins the work. But before that the work was uncertain and raw; it was more sexual and emotionally charged.

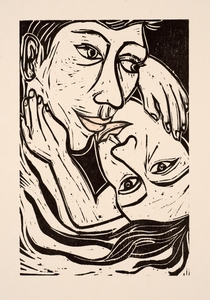

Witness II

1999, ceramic by Eileen Cooper (b.1953)

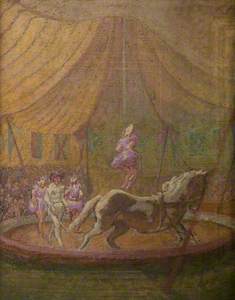

Later in life, the anxieties of watching children grow inform the work, before the presence of children disappear altogether. In my more recent paintings, I'm concerned with looking outside, beyond myself, there is a cooler detachment. There are a few paintings about the circus and dance, for example, the preparations for Akram Khan's Giselle.

The show tracks not just my life journey, but the journey I've had with process and materials. Printmaking plays a big part of it, as well as the ceramics, which haven't been seen before. We could make the connection with my ceramics and those of Picasso in Leicester's collection.

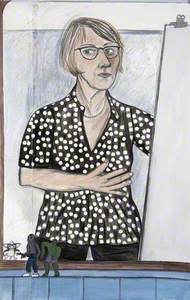

Lydia: You've said you want to capture the female experience in a universal way, though your work is also autobiographical. Self-image and the relationship with the self is something you have previously said fascinates you. Are you reflecting on and perhaps challenging the tendency for women to harshly judge themselves?

Eileen: I think the scrutiny of the self is a more of a painful preoccupation for younger women, many of whom have been targeted by our culture. Every generation was aware of what we were supposed to aim for, but in terms of how we look and present ourselves to the world, I don't think that my female subjects are judging themselves from a place of insecurity. Rather the mirror and the act of looking at themselves is a quest for knowledge, self-knowledge. The mirror becomes a metaphor for ways of seeing and duality; a woman looking at herself.

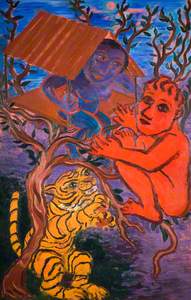

Trapeze

2012, oil on canvas by Eileen Cooper (b.1953)

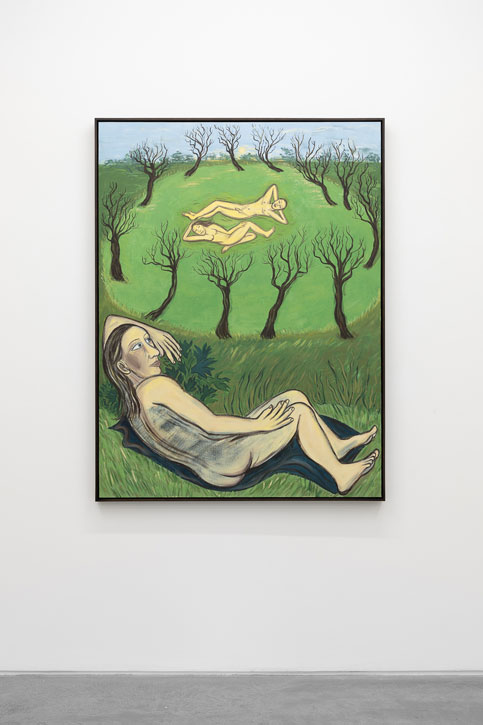

Lydia: Your show 'Somewhere or Other' at Huxley-Parlour earlier this year situated female figures in the landscape. They suggest a kind of yearning for nature, simplicity but also freedom. Did the restrictions we have all faced over the past couple of years inspire this body of work?

Eileen: Absolutely. Finally getting out into the world at the end of the lockdown, to have that physical and emotional connection with the landscape inspired me greatly. We spent time in Suffolk where the lushness of the countryside certainly entered my work.

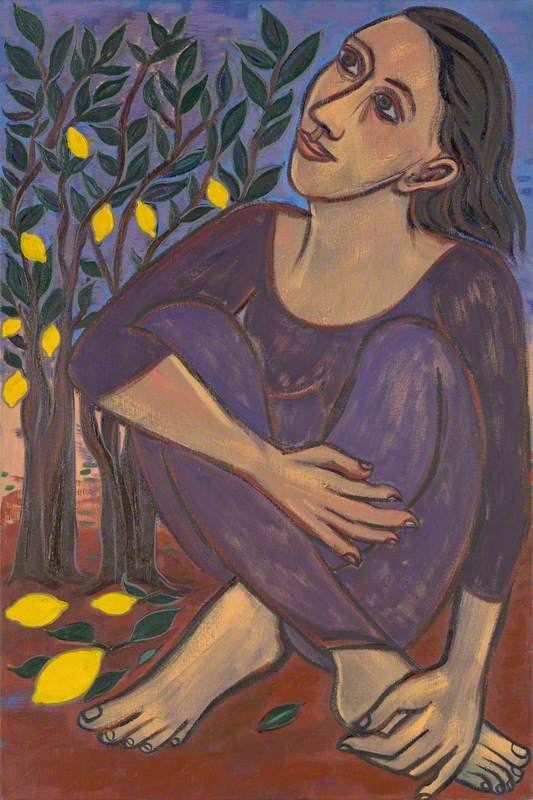

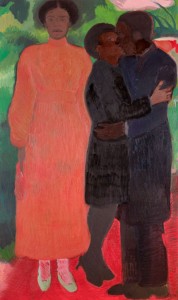

Personal Space

2019, oil on canvas by Eileen Cooper (b.1953)

I've always been wary of using the colour green in my work, and I've never been particularly responsive to landscape art, but I felt the need to engage with the landscape from the inside out. By that I mean, I wanted to capture it through a bodily and physical engagement, from the earth up. For that reason, my figures are lying down on the grass; they are soaking up nature. There was something fresh and honest about those works that was different for me.

Installation view of 'Daylight' and 'The Wild Place'

2021–2022, oil on canvas by Eileen Cooper (b.1953)

Lydia: What does a typical day for you look like?

Eileen: For most of my career I've had a part-time teaching job, which was on and off over forty years. A teaching day ruled out any time in the studio. And when I had my children my studio day would need to start early. Often now I won't start working until late morning, maybe 11am. I like to go for a walk with the dog first. I tend to work in daylight. My longest day is five hours, after that I'm physically quite tired. If I'm not working or a bit stuck, I find tidying the studio gets me working. Inadvertently I pick up a piece of charcoal or a paintbrush. My studio isn't large so I have to keep on top of it.

Winter Sun

2022, oil on canvas by Eileen Cooper (b.1953)

Lydia: In past interviews, you've said that art has always been a form of escape for you, though you had never planned on becoming an artist professionally. When did that change?

Eileen: Where I grew up, to be an artist wasn't a 'known' thing. Let alone the knowledge that women could be artists. I decided to go to art school when I found out they existed, although I didn't think this would necessarily lead to becoming an artist. Even when I graduated from the Royal College of Art it wasn't clear whether I could continue being an artist, I didn't know how to survive financially. But at that time it was easier to get funding as well as a studio. Now of course it's too expensive.

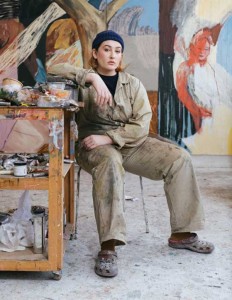

Eileen Cooper

Lydia: What advice would you give to aspiring artists today who are thinking about going to art school?

Eileen: I would say if you have the opportunity to do further education, then studying art is a wonderful thing and will lead you into many other opportunities. Art can be broad, you won't necessarily end up being a painter. You could become a film maker, games designer, photographer – there are so many paths to follow.

The problem now is that everything is so expensive and the student numbers are so vast, you have to be very strong as a young person to make sense of it. It's not easy. I think art schools are better when they are smaller. There are lots of options now, you can dip in and out of courses, or take a part-time course. You can access more online. I'm a big fan of the less costly independent art schools that are opening up.

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

'Parallel Lines: Eileen Cooper and Leicester's Art Collection' at Leicester Museum and Art Gallery, New Walk, Leicester runs until 27th November 2022