In the series 'Seven questions with...' Art UK speaks to some of the most exciting emerging and established artists working today.

Emma Talbot isn't much of a planner. 'If I planned it all out beforehand, I imagine I might get a bit bored by the time it was complete,' she says, smiling but also serious. 'I like the sense that I'm inventing as I go along. It feels very lively to me.'

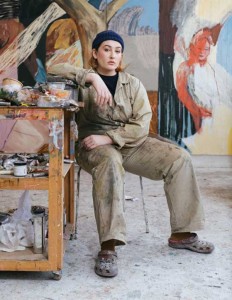

Portrait of Emma Talbot in her studio in Reggio Emilia, April 2022

Working across drawing, painting, sculpture and animation, the London-based artist makes richly detailed installations that respond to both her personal experience and societal and geopolitical issues such as feminism and climate change. Her art incorporates materials from paper to silk and combines vivid imagery with poignant pockets of text. Among other things, it's about storytelling.

Talbot was born in Stourbridge, a market town in the Midlands, and raised in Kent. After completing her foundation and undergraduate degrees, she attended the Royal College of Art for her MA. Since winning the 8th edition of the Max Mara Art Prize for Women in 2020, she's been busy, participating in the 59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia curated by Cecilia Alemani, and completing a residency organised by the Collezione Maramotti in Reggio Emilia, Italy.

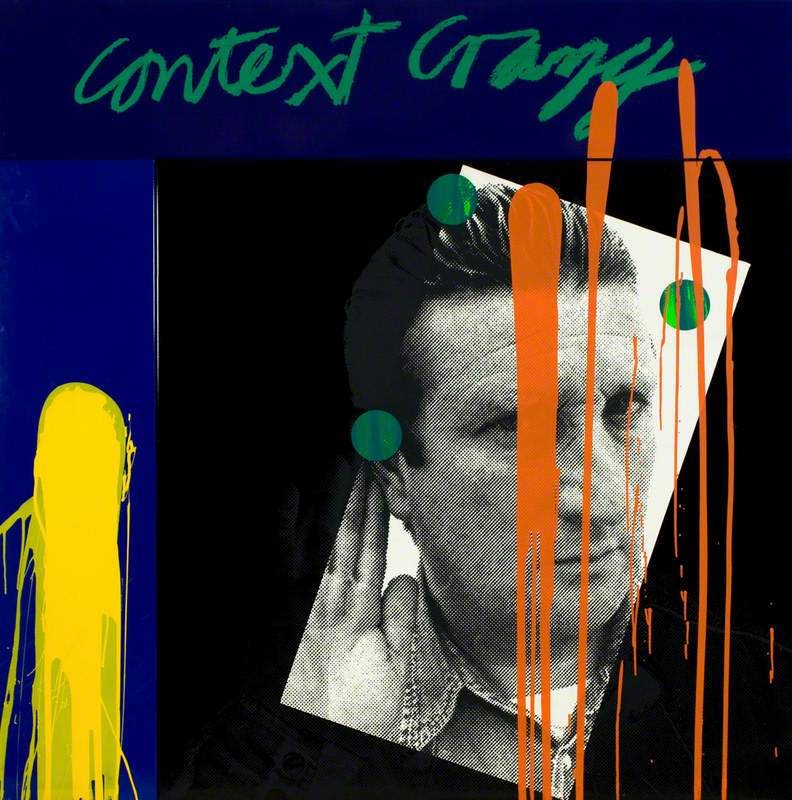

Installation view of 'The Age/L'Età', Max Mara Art Prize for Women: Emma Talbot

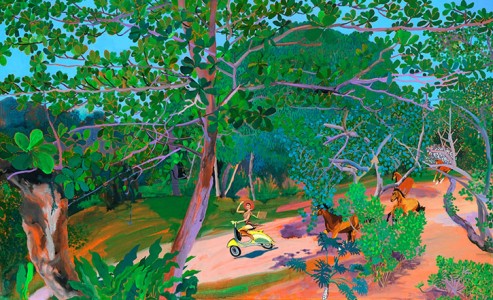

It was during her residency that Talbot created the immersive installation on display at the Whitechapel Gallery in London. She spent six months researching classical mythology and pottery, textile fabrication and permaculture, and visiting archaeological sites and volcanic terrain.

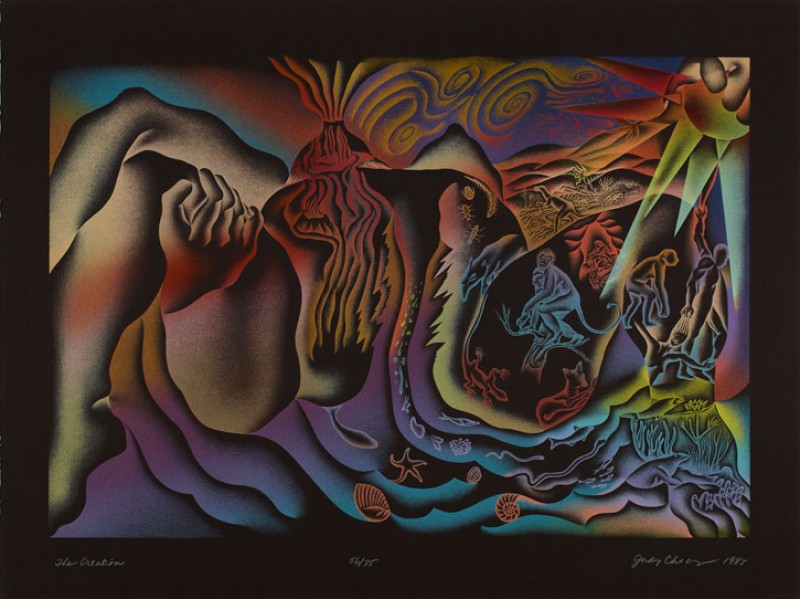

The resulting work, The Age/L'Età, takes as its starting point Gustav Klimt's The Three Ages of Woman (1905) and The Twelve Labors of Hercules, and explores themes of ageing, governance and nature. We sit down with Talbot to hear about her influences, narrative, and challenging ancient power structures.

The Three Ages of Woman

1905, oil on canvas by Gustav Klimt (1862–1918)

Chloë Ashby: What drew you to Klimt's painting and how have you used it as the basis for this new body of work?

Emma Talbot: I hadn't seen the painting in real life until the residency, but it had been on my mind. The elderly female figure was a bit of a spectre for me because she has long grey hair like mine, and I almost projected myself into her. She has her head in her hands, as if she's ashamed of her ageing. I wanted to make her a protagonist, and to consider what she would do if she had agency. I imagined her as a sole survivor in the future, trying to figure out how to live after an apocalyptic disaster, how to survive without technology and the structures we have around us. I don't think of her as a hero because heroism is quite a narrow trajectory, but as an unexpected and exciting protagonist.

Installation view of 'The Age/L'Età', Max Mara Art Prize for Women: Emma Talbot

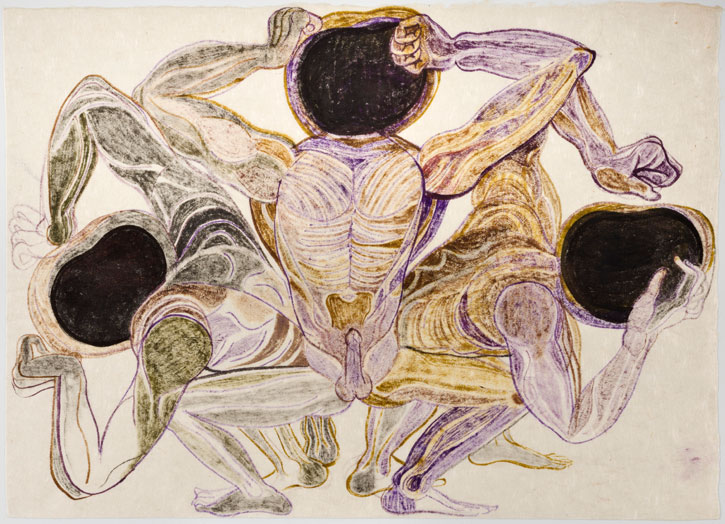

Chloë: How did the Labours of Hercules come into it, and how did you go about putting your own spin on them?

Emma: I thought, if this figure really had to construct a new future, then ideologically she would look at some of the structures we have in place and rethink them to make a fairer society. At the time a lot of the rhetoric the government was using referenced the classics; if you use that rhetoric, you're saying power has always come from the same place and always will do, and I liked the fact that this protagonist could look at things in different ways.

The Labours of Hercules tracks the development of a young man into an old man who becomes a god. There are twelve stories of how to deal with or attain power, and what struck me was that they were aggressive – Hercules resolves them by killing or capturing or stealing.

I decided that my character would come at these problems in a different way, thinking through them and trying to find a resolve that was mutually beneficial for all parties. So, I applied to each trial a contemporary issue, then I let her think around it in terms of how things could be structured differently to make life a bit more even.

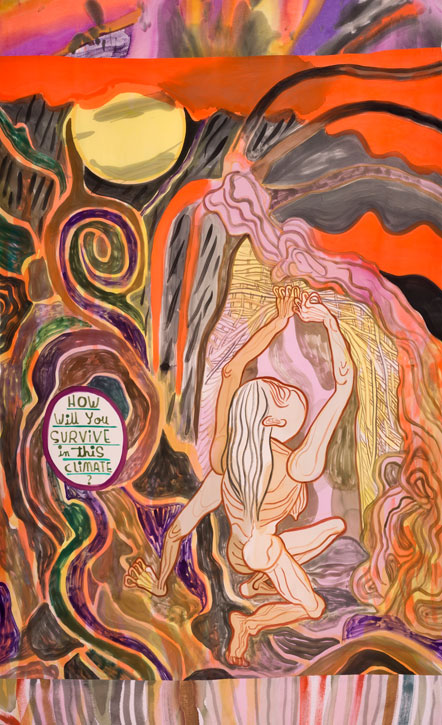

Detail from 'Volcanic Landscape'

2022, acrylic on silk by Emma Talbot (b.1969)

Chloë: Retellings are rife in fiction, and more and more artists appear to be reinterpreting art history in their work. Why do you think it's helpful to look back to start new conversations?

Emma: I think it's partly that this fixed sense of who holds power is becoming quite authoritarian, and in that situation, it's natural to try to offer alternative tellings, versions and readings to suggest that the dominant power isn't the only power. It's a way of exploring how we understand things. And it's a way of challenging without just using the same aggressive tactics.

Installation view of 'The Age/L'Età', Max Mara Art Prize for Women: Emma Talbot

Chloë: Do you begin with text or images?

Emma: My starting point is always drawing – I draw with a brush and watercolours – but sometimes that drawing is text. I'm just painting my thoughts, and we have different layers of thinking: sometimes we think in words, sometimes we have an almost photographic sense of something.

I start with a skeletal set of drawings that make me know the subject I want to address, then I start painting. I might leave spaces where I know there will be text, and I just don't know what it is yet, or I might not know what all the images are. I like there to be a directness where, when I'm painting, I'm inventing.

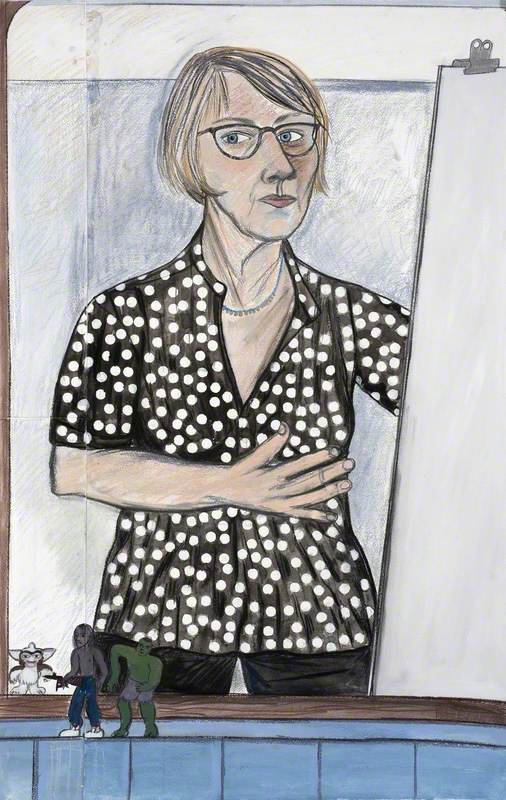

Detail from 'The Trials'

2022, watercolour on Khadi paper by Emma Talbot (b.1969)

Chloë: How does the text both support and challenge the images?

Emma: The images and the text sit alongside each other as thoughts that might correlate, but they don't serve each other – the text doesn't describe the images. They do different things. In that sense, it feels like a free space for me to figure out how to construct a way of telling that doesn't have a pre-formulated format. It's for me to decide whether a piece of text should be enormous or tiny or coloured; all the visuals that make the text what it is are also important.

Chloë: Your art spans many media. Do you feel most comfortable with one in particular?

Emma: No, it just depends on the idea and how I think it should be realised – I have a vague idea of what I want to make, then I see it as I make it. The materiality is important. It's usually something that doesn't exist that I want to see in three dimensions, becoming a figurative or physical thing. Other things should be animated because they need to move and have sound.

I've just finished making a 25-minute animation for the Whitechapel show, and now I don't want to make another animation for a while because I spent so long concentrating on that. It's always the same. It's nice to move around and feel enthusiastic about coming back to something. By that point, I'm excited about it and I've forgotten the harder parts.

Emma Talbot in her studio in Reggio Emilia, April 2022

Chloë: How do you go about combining the personal and the universal?

Emma: For me, there isn't a big barrier between the two. I think we're always balancing emotive, subjective thoughts with being people in the wider world. We do it every day, so that's quite natural.

The thing for me is, does it feel true and honest? Is it really what I think and what matters to me? If it is, I can sense it, whereas if I were just picking a subject because it was prevalent, I wouldn't have that same feeling. So, there's a real rule about me absolutely believing in it. And at that point, it doesn't matter how important it is to other people. It's more that, to me, this is urgent, and I want to do it.

Chloë Ashby, freelance writer and author

'Emma Talbot: The Age / L'Età' at Whitechapel Gallery, London runs until 4th September 2022. To find out more about the artist you can visit her website.