In the series 'Seven questions with...' Art UK speaks to some of the most exciting emerging and established artists working today.

The figurative paintings of Sahara Longe are reminiscent of the allegorical and resplendent paintings of the Renaissance and Baroque – in particular, those of Peter Paul Rubens which inspired her latest series of works. Painted in a realist manner, Sahara's work maintains loose, expressive brushwork that offers a sense of dynamism. Layers of thinly applied, luminous paint highlight and reflect spots of light, on the brow or cheekbone of a sitter. Her works convey a timeless quality; they are symbolically loaded with history, yet distinctively rooted in the contemporary.

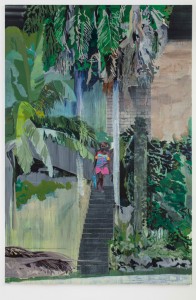

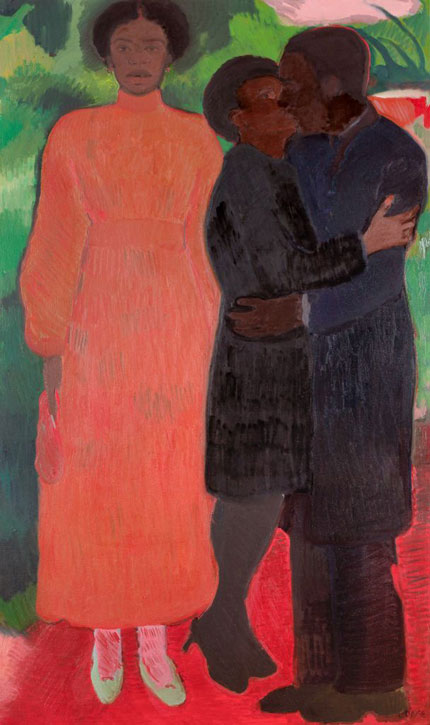

Garden Party

2021, oil on jute by Sahara Longe (b.1994)

What makes Longe's works so distinctive is her insertion of Black figures into classical backdrops that we have largely associated with white Biblical, mythological or aristocratic figures throughout the centuries. Pointing to the omission of Black figures in the history of European art more broadly, Sahara's work offers a glimpse into a hypothetical history of art.

Based in London, Sahara attended the Charles H. Cecil Studios in Florence, where she learned the traditional painterly processes and techniques used in Renaissance painting. After a successful sell-out show at her gallery, Ed Cross Fine Art's booth at 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, she is now back in Italy, at the Palazzo Monti Residency.

Continue scrolling to read my interview with the artist.

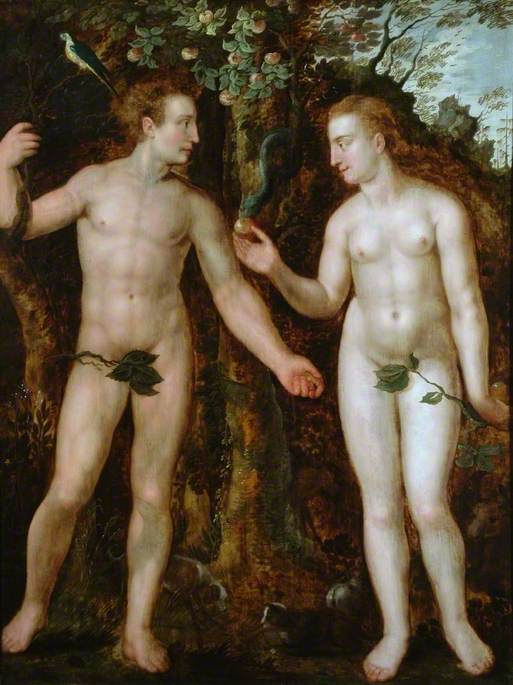

The Fall of Man

c.1628–1629, oil on canvas by Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640)

Lydia Figes, Art UK: Your work could be interpreted as a revisionist approach to art history – in particular, European white art history. What initially led you to develop this visual vocabulary?

Sahara Longe: I wasn't intending to revise history; it initially came out of a desire to learn about painting. I decided that the best way to develop my skill would be to copy from Old Master paintings. During lockdown I was struggling with my work and technique in general. So I looked to one of my favourite paintings, The Fall of Man by Rubens (a scene previously painted by others, including Titian).

The Fall of Man

2020, oil on jute by Sahara Longe (b.1994)

I had already started learning about traditional oil painting techniques at the Charles H. Cecil Studio in Florence – it was four years of classical painting in total. When I left I started to create large-scale paintings in the classical style, but I was still grappling with composition and how to place figures. Imitating the compositions found in Old Master paintings helped me, but I wanted to add my own twist. I changed the figures to Black figures because it was more interesting to me, it felt more comfortable. It didn't really occur to me to use white figures.

Lydia: What art historical references or artists tend to interest (or bother) you the most?

Sahara: I'm interested in so many artists, historical and modern, but when I was studying classical painting a lot of these artists were pressed upon me so that's where the interest developed.

I've always been interested in German Expressionism, and those artists who use colour to convey emotion. I'm also interested in the German movement of Die Brücke and the artists who used heavy lines to guide the viewer's eyes around a painting.

Although my work references art history, I'm not trying to provide a critical commentary. I respect artists such as Titian and Rubens, and I wanted to continue that visual language but put my own take on it. It seemed boring to simply recreate the subject of Adam and Eve as it has been done before.

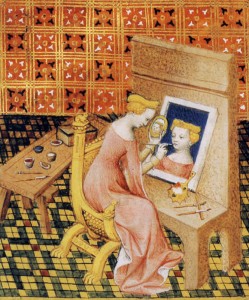

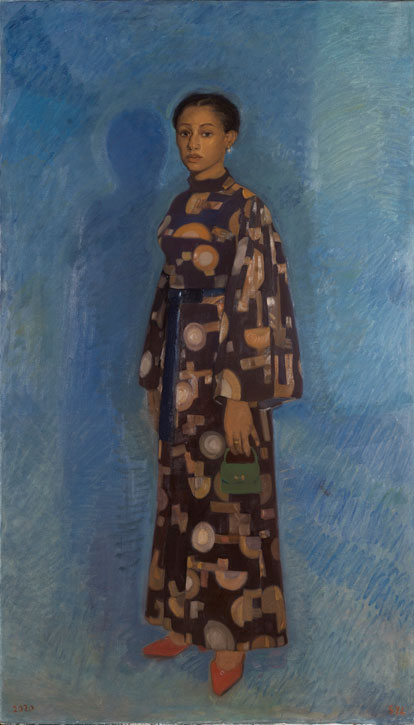

Edwina

2020, oil on jute by Sahara Longe (b.1994)

You'll notice other small differences between my painting and Rubens'. In the background of my work The Fall of Man (2020) a ship is visible between the figures of Adam and Eve – this was supposed to represent a slave ship. I was playing on the idea of the 'fall of man' not from the Biblical perspective, but the fall of Africa during the transatlantic slave trade. This was the real tragedy of humanity.

In my version of the subject, the forbidden fruit has also been replaced by glass beads, referencing the act and history of trading objects for enslaved peoples. I had been in Sierra Leone just before completing this work and visited the Banana Islands that were historically slave islands. It was sad to learn about the history, so it was playing on my mind while I created this work.

Lydia: In your rendition of the subject matter, the gaze of Eve meets the viewer's. Can you tell us more about the decision – were you thinking about the male gaze?

Sahara: It felt more natural to allow Eve's gaze to meet the viewers, and this was something I painted instinctively. I wanted Eve to engage directly with the viewer, as she becomes a vessel for the broader story. It's almost as if her confrontational glance serves as a warning, a prophecy of what is to come.

To have the figure of Eve stare back at the viewer also makes them feel more like they are part of the painting (for that reason, the parrot also looks out at the viewer). It wasn't so much about criticising the male gaze, and I was also thinking about how to make her face appear sensitive and gentle.

The Three Graces

1630–1635, oil on canvas by Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640)

Lydia: Your painting Three Graces appropriates the mythological tale that has been depicted by many artists throughout the centuries, from Botticelli to Raphael. But why select this subject matter?

Sahara: The subject matter of the Three Graces is all about idealised beauty – so I wanted to see my own version. I began by looking at the Rubens Three Graces and then used photographs of friends and my mother for the faces.

Three Graces

2021, oil on jute by Sahara Longe (b.1994)

The female nude is the most beautiful and satisfying thing to paint. There is something incredibly rhythmic about creating the female form – from painting curves and being more fluid with your brushwork, to capturing the texture of skin, which I finished with a shiny glaze. While painting all three female figures together I was thinking about the harmony of the curves and overall composition. I personally find painting the male nude less satisfying – it's somehow less poetic.

Installation view at 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair

Lydia: What is your process, or how long on average does it take you to complete a work?

Sahara: It really depends. With a large painting it can take up to three months because I'm using a lot of the traditional medium – it's a combination of tree sap, linseed oil and turpentine. It helps give a shine to the skin, that's why all my paintings are very luminous. I have to add many layers over a long period of time, so it can take several weeks. Three Graces was in my studio for over a year. I was unhappy with it so I worked on The Fall of Man and then returned to it later.

But I've completed other works that have taken less than an hour. For example, my painting in the show that featured the green skull. This work was partly completed quickly because my dad had gotten sepsis and was ill at the time. Sometimes you don't need to spend up to two months staring at one piece of work.

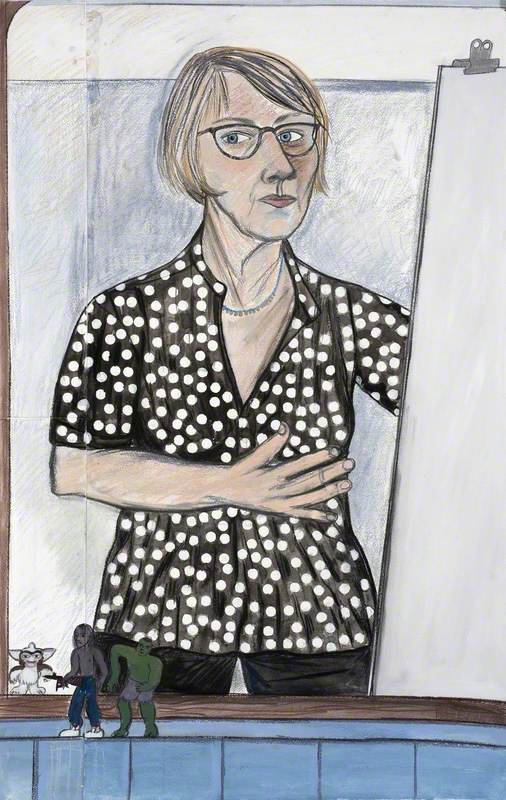

Self-Portrait with Brushes

2021, oil on jute by Sahara Longe (b.1994)

I know when a work is finished because of an immediate response to the painting. It doesn't have to be 'perfect', it will just come down to the feeling I get once seeing it with fresh eyes the next day, or after some time apart from the work. All you need is a split second to know whether you have an emotional connection with the work. Painting should be enjoyable, it can't just be about the conceptual or symbolic analysis. It has to be visually interesting too.

Lydia: Do you have any studio rituals or daily habits?

Sahara: I listen to really terrible audiobooks – like really crap 'whodunnit' stories. That's the only way I can concentrate. So yeah, either bad audiobooks or aggressive dance music!

Sahara Longe

Lydia: What advice would you give to aspiring artists?

Sahara: Choose your art school wisely. If you want to learn to paint I recommend the academies and art schools in Italy (it's also cheaper!). I wouldn't have been able to get the basic training without going there.

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK