In the series 'Seven questions with...' Art UK speaks to some of the most exciting emerging and established artists working today.

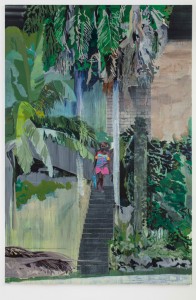

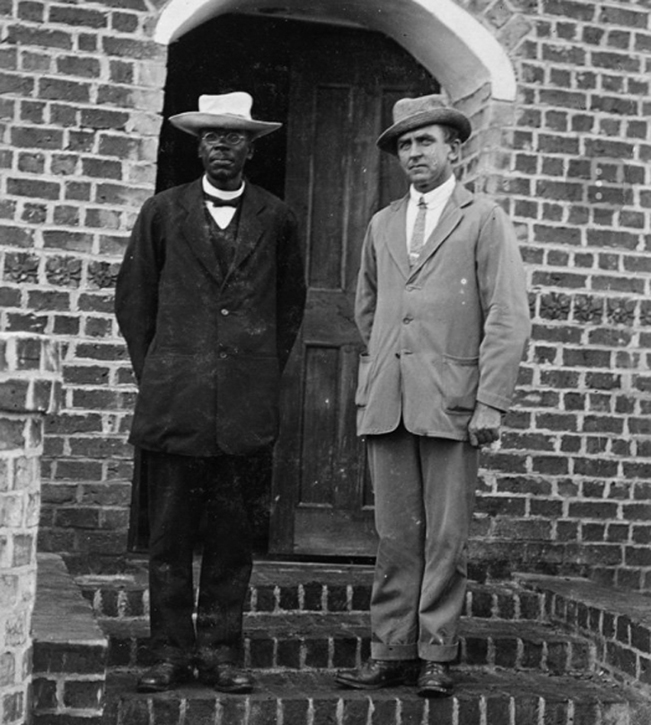

Oxford-based artist and writer Samson Kambalu is the latest artist commissioned to mount a sculpture on the Fourth Plinth in London's Trafalgar Square. The sculpture, entitled Antelope, is based on a photograph of Baptist pastor and anti-colonialist John Chilembwe and European missionary John Chorley. Chilembwe is wearing a hat in defiance of a colonial rule that forbade Africans from wearing hats in front of white people.

John Chilembwe (left) and John Chorley (right)

1914, photograph by unknown artist

Samson's practice, spanning sculpture, film and interactive installation is underpinned by play and by the Chewa concept of Nyau. Nyau is a secret society, a masquerade and a philosophy in southern Africa, including in Malawi where the artist, a Chewa himself, grew up.

It's clear that these principles permeate his life, beyond just his art – during our discussion, the artist changed his hat twice while diving deep into economics and philosophy and picked up his guitar while theorising on conceptual art. For the Associate Professor of Fine Art at the Ruskin and fellow at the University of Oxford's Magdalen College, the seriousness of life can be understood through playfulness and joking. And he's letting us in on the punchline.

Samson Kambalu

Julia DeFabo, Art UK: You've talked before about the role of the gift economy in your work. What is a 'gift economy'?

Samson Kambalu: Capitalism starts with the idea that we lack and we have to save up, but with the gift economies, like in southern Africa, we start with the idea that we have too much. In a gift economy, the world is the Garden of Eden, and this is a problem to solve, there are too many fish in the sea, too many crops, too many animals in the bush. What are we going to do with all this stuff? Art is primarily to take care of this excess. My problem is abundance, the abundance of life, the abundance of time.

A gift usually leads to obligation. Like at Christmas, your brother or sister buys you something, you feel obliged to buy them something. But this exchange is seen as petty in a gift economy. You can't get rid of excess through exchange.

Julia: If you aren't getting rid of this excess through exchange, how are you getting rid of it? And how does this relate to your otherworldly, black and white films entitled Nyau cinema?

Samson: It must come out through play. Instead of going to the market, we will have a Nyau mask festival or rave where people go and give without this petty exchange. The mask allows you to be magnanimous, to give without expecting anything in return.

And for me, the films allow me to get into that world. Nyau cinema is a way of doing time in a much more luxurious way. We are trying to avoid petty exchange and instead encourage real expenditure which comes through play.

Julia: How did you start making the films?

Samson: I made the films out of necessity. I was anonymous in hotels and different cities, and I got tired of going to museums and taking in all this information. So, I decided that when I travelled I should be interacting with the city. When I did that, the films came to me. And these films, kind of like [Nyau] masking, belong to this non-linear time. I walk the cities, and I find these places that transform me. My identity is always changing depending on the film set I find.

What is called the imaginary and the ego in philosophy are forms of Nyau masking. The ego is an illusion that we have to create to constitute ourselves. So don't go throwing your ego around pretending it's real, make a mask. I need to make these films to constitute myself as a person. If I don't, I become a victim of somebody else. Before I was making Nyau films I was just a subject to other people's Nyau, subject to how people think of Africa.

So I started making my clips and I put them on Facebook. I didn't even think I was making art, they were more like letters home for my sisters because the aesthetic I was using is how my sisters and brothers and I watched films [as children in Malawi], the films always breaking down.

Julia: Could you tell me more about the role of play in these films and in your work in general? Is there a humour to it?

Samson: It is a kind of humour, perhaps you see it sometimes in Charlie Chaplin. I do humour, but it is not childish play in the sense of innocence. A lot of Westerners used to tell us, 'You Africans are childlike.' It took me a long time to begin to make connections between play and philosophy and economics.

Play – or as we call it in Nyau, 'the great play' – is what connects us to the universe. We need play, we need creativity and we need the aid of masks or the aid of art. And why do we need to enter that zone? It's because that is the place of real generosity. When we enter that zone of real play, we just shine like stars, and everybody thrives.

Holy Balls

installation by Samson Kambalu (b.1975) at the Venice Biennale ('The Last Judgement')

Julia: For your work Holy Balls, you covered footballs in pages from the Bible and asked people to 'exercise and exorcise' by playing with the balls. Is this a subversive work?

Holy Balls

installation by Samson Kambalu (b.1975) at the Venice Biennale ('The Last Judgement')

Samson: This was my first conceptual work. I made it in 2000 when I was painting. I took a break from painting and was just kicking a football in the studio against the wall, and I decided, talking to my sister, that I was going to take pages from the Bible and paste them around the ball. And when I finished, this is when I stopped painting. This was my moment as Paul on the road to Damascus. My sister thought this was great, and she's a Christian. And actually when I took this work out, contrary to what you might think, because it looks blasphemous, Christians loved it. And when I took it to philosophers, they loved it too.

Julia: Your Fourth Plinth sculpture is based on a photograph of the Baptist pastor and anti-colonialist John Chilembwe and European missionary John Chorley. It's a figurative, realistic sculpture. Do you think it is a departure from the playfulness that is in your other work?

Samson: Oh, come on, that's the most playful work I've made! The Fourth Plinth is more playful than Holy Balls. You have the white guy [John Chorley] and next to him is the Black guy [John Chilembwe] who is twice as big as him. That's not playful? You can't do that in the middle of London. Trafalgar Square is the heart of the British Empire. This is the place of authority of whiteness. The Fourth Plinth sculpture is the most playful, most subversive thing I've done.

And size matters in sculpture. Like in Egyptian art, you see some things depicted bigger and some that are depicted smaller, and of course this matters. Or if you look at posters for Spaghetti Western films, the main star is big, and the supporting act appears smaller. The plinth was made for a horse, so one figure is the size of a rider and the other is the size of a horse. I gave this weight of the horse to Chilembwe. I've made Chilwembwe the size of an antelope.

Masquerade mask

20th C, wood, horn, hair, fur & other materials by Cewa artist Mr Dazi

And Chilembwe means antelope. Chilembwe also alludes to the Nyau principal mask, which is a womb disguised as an antelope. It is at the British Museum too. So I think John Chilembwe chose it as a made-up name. He embraces his heritage, very subtly. I was searching for the hat he wears in the photograph, and I discovered that he was actually wearing the hat turned to the side so that the profile is almost like antlers. He really becomes an antelope.

The Fourth Plinth sculpture is a conceptual work of art. It's deceptive because it is figurative, but if you are just looking for figures, there is something awkward about it. You have to really think, 'There's a horse and a man there, but why has the horse turned into a man?' When you think about empire, it's almost like the horse has thrown off the rider and become a man.

Julia: What makes an artwork a 'good' work of art for you?

Samson: A lot of monuments are coming down in America or the UK because they were just kind of complimenting power instead inserting art into it. If you write for a king and you just flatter him, your poem will be lost to history. But if you insert art into it, it will survive. Art is something that can be taken in different ways, that has multiple layers of meaning. I'm not interested in just making a monument to Chilembwe.

As a teenager, I didn't want to go to school. All I wanted to do was play my guitar and paint. But I was sitting in English literature class and my teacher started reading from Hamlet and I had to stop. It was like, wow. Shakespeare was talking about England but he has a facility with words that goes beyond England or the specific time he was in. His poetry is beyond place and time. And good art is like that. We might not still go to church, but we still go see Michelangelo's Pietà or we still go to see Bernini's Ecstasy of Saint Teresa because there is something true about it.

Julia DeFabo, Art UK's Social Media Manager