In the twenty-first century, one could argue that there are now as many visible female sculptors as male. The art world is increasingly balanced, in most ways, if not all. But it is easy to lament the lack of female presence historically, and wonder how to put it right, given the difficulty of redressing inequality retrospectively.

However, women sculptors are not quite as unusual as you might think. You just need to know where to look, and Art UK proves to be a helpful resource for that. Women sculptors haven't always made small sculptures or decorative objects – some of their works are so very public that it seems surprising that they escaped our notice in the first place.

Elizabeth, née Farren (1759–1829), Countess of Derby

c.1788

Anne Seymour Damer (1748–1828)

Anne Seymour Damer (1748–1828) is one of the better-known historical practitioners, and her work is reasonably widespread. Her range was unusual – from sweet little lap dogs to the majestic George III in the National Records Office of Scotland.

Because she was well connected and quite a public figure, her sculpture used to be treated dismissively, but the portraits (V&A, NPG, Ranger's House), and other allegorical works (e.g. those at the River and Rowing Museum) deserve serious attention.

Mary Thornycroft, née Francis (1809–1895) is another remarkable figure. Although much patronised by Queen Victoria she has faded from view. Regularly described as the daughter, wife, and mother of sculptors, she (and her artist daughters) are often overlooked. Although most of her works are in the Royal Collection, a lovely bust is in Leeds Art Gallery, as are the Thornycroft family papers.

Thornycroft taught the Queen's daughters, and Princess Louise (1848–1939), Duchess of Argyll became quite accomplished, winning the commission to make the Golden Jubilee statue of her mother outside Kensington Palace.

Like other women sculptors, she had to put up with insinuations that the carving had been done by men, which was anyway very often the case for sculptors, of whatever gender. Small-scale versions of this composition are in Bournemouth and Leeds. Countess Feodora Gleichen (1861–1922), another royal sculptor, and another sculptor's daughter, is also present in Hyde Park, with her Diana Fountain.

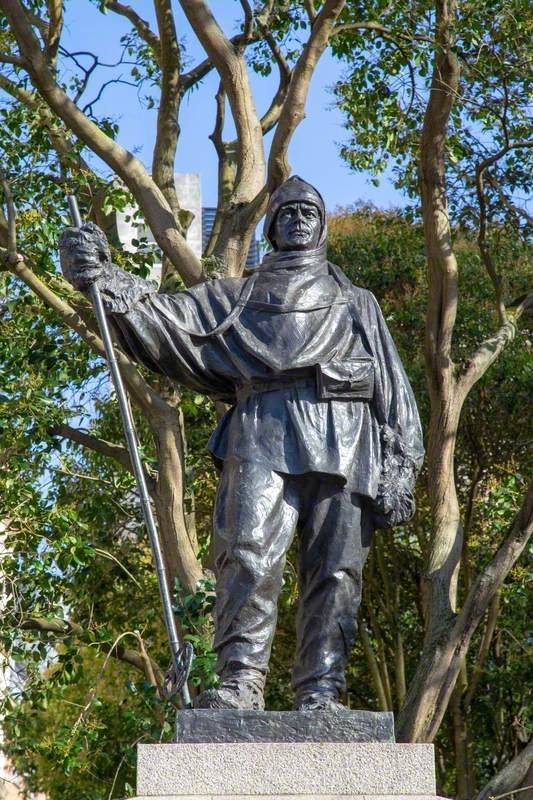

The homage to Robert Falcon Scott in central London (1915) by Kathleen Scott (1878–1947) is a major public statue, but its status may be undermined by the fact that Scott was the explorer's wife.

Captain Scott (1868–1912)

1914–1915

Kathleen Scott (1878–1947)

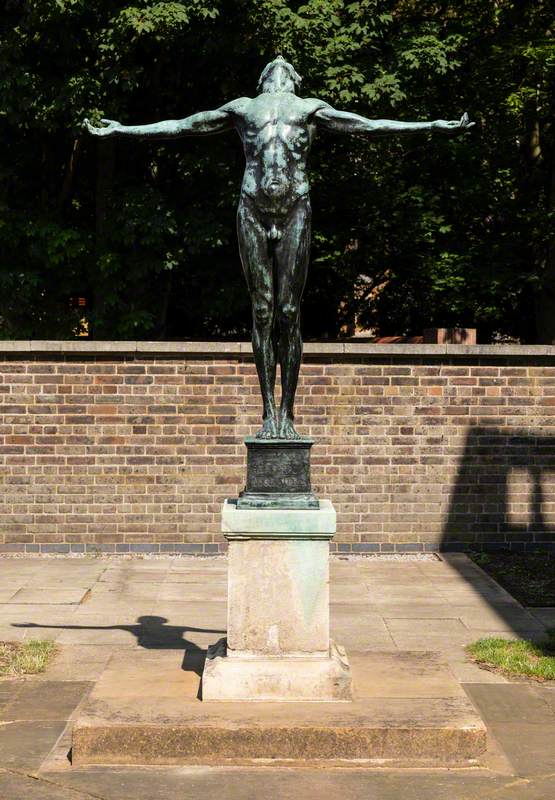

Before meeting him, however, she had trained at the Slade and in Paris, where, like many young sculptors, she was enamoured of Rodin's example. Her uncommissioned war memorial, showing a naked youth with upraised arms, later ended up outside the Polar Research Institute in Cambridge, with its message repurposed. Smaller versions exist, with the original inscription extant, as at Anglesey Abbey.

May Eternal Light Shine upon Them

1920

Kathleen Scott (1878–1947)

With the opening of higher education to women, many more undertook training, if mostly as art teachers. Those women ready to take on the making of statuary tended to be those with a family background. Other women, such as Mary Seton Watts (1849–1938), were able to be more ambitious because of their marriage to artists, even if their husbands' celebrity overshadowed their wives' identities.

Queen Saint Margaret, Queen of Scotland (c.1045–1093)

Mary Seton Watts (1849–1938)

Nonetheless, they are probably better represented outdoors than indoors, whether on public buildings, in churches or graveyards. Women's less public roles often allowed them to work in more innovative ways, and in more varied media, as Mary did at Compton, with a team of local pupils.

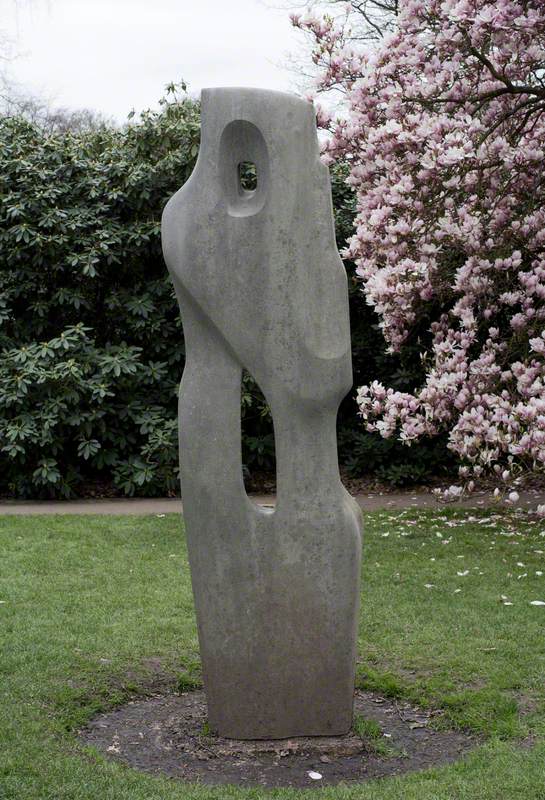

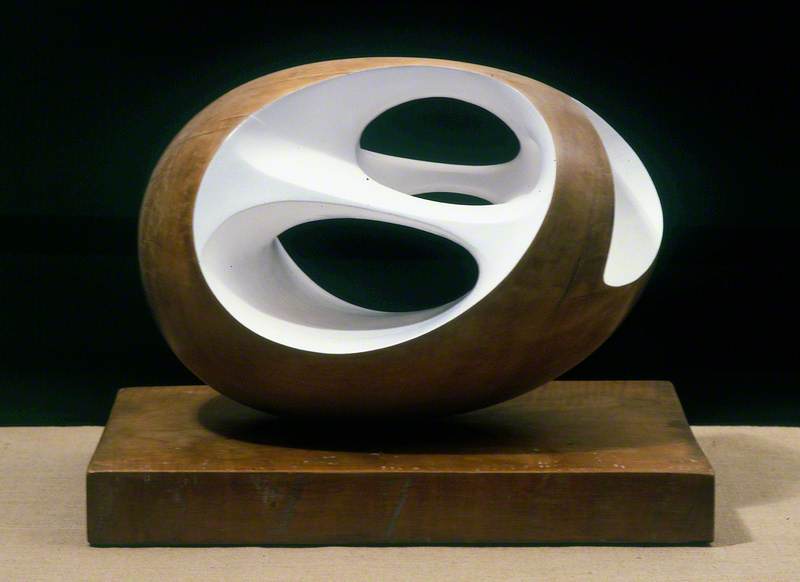

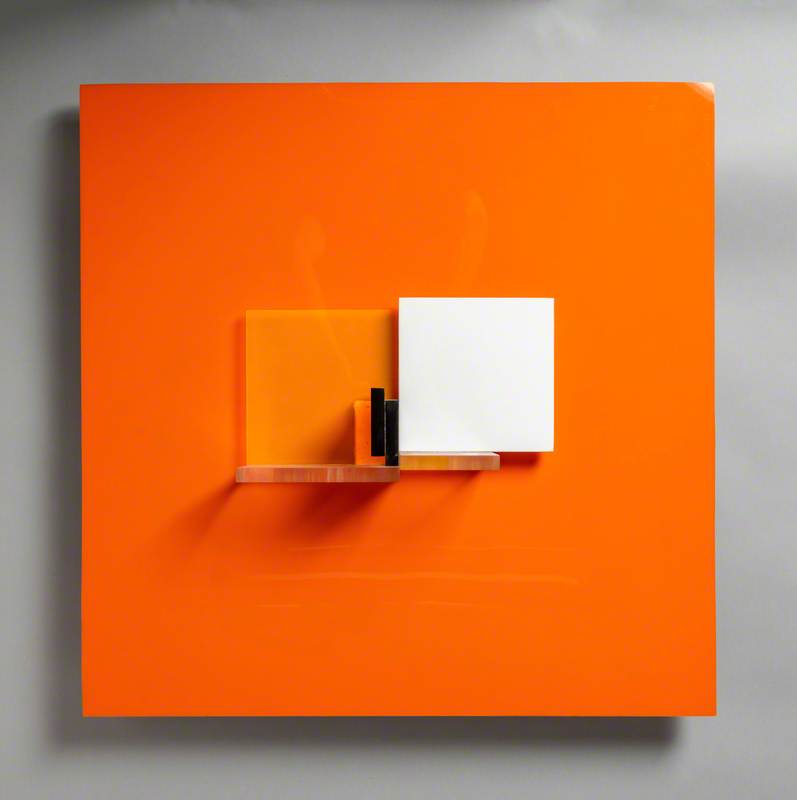

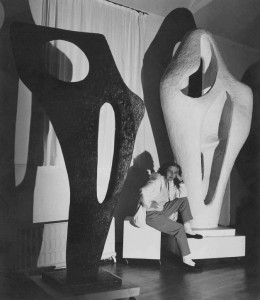

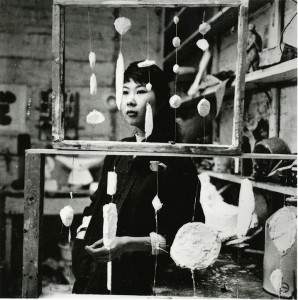

It was only in the twentieth century that sculptors, women like men, freed themselves from the burden of portraiture. Artists who came of age during and immediately after the First World War – Marlow Moss, Paule Vézelay, Gertrude Hermes, Barbara Hepworth, Mary Martin – increasingly had the option to make non-figurative works, and all those cited took it with aplomb.

In so doing they simultaneously loosened the ties of family and class connection, and began to create a space that was more immediately theirs.

Ironically, the new understanding of public space after the Second World War once again led sculptors back to figuration, now used to represent ideals of civic and communal welfare. If artists like Hepworth and Martin largely succeeded in tailoring their abstract language to a wider public role, others, like Betty Rea and Karin Jonzen, adapted the lessons of the life class to the civic plaza.

Portraits of great men were no longer much in demand, but portraits of anonymous women and children were. This kind of contrast – between the named male and the anonymous female – was visible in sculpture as in wider culture.

Penelope Curtis