It's a family row, a domestic: a petulant child, a stern father and a mother whose reproof is tempered by relief.

Christ Discovered in the Temple, sometimes known as The Holy Family, by Simone Martini (c.1284–1344), is in the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool. It's a small painting, nearly 700 years old – a jewel among many from pre-Renaissance Siena. It's startling in its expression of the emotions of exasperation and obstinacy, played out by the most exalted of families.

The story goes that after a trip to Jerusalem, Mary and Joseph headed back to Nazareth, but Christ, then a boy of 12, stayed behind. Assuming he was among the travelling group, Mary and Joseph only realised he was missing after a day. Two days later, they found him in a temple in Jerusalem in discussion with the elders.

Any parent can imagine how desperate Mary and Joseph must have been. But Christ's indignation on being reproved is also familiar: for children want their freedom and find parents overprotective and unduly fussy.

Christ's explanation for his absence is his first recorded utterance. According to Luke 1:41–52, when they found him in the temple, Mary asked: 'My son, why have you treated us like this? Your father and I have been searching for you in great anxiety.' To which Christ replied: 'What made you search? Did you not know that I was bound to be in my Father's house?'

Simone's depiction of this episode, coming so early in Luke's account of Christ's life – just 40 lines or so after his birth at Bethlehem – is said to be unique in art. Although there are numerous portrayals of Christ with the elders in the temple, and others in which Mary and Joseph are seen arriving on the scene (as in Jacopo Bassano the elder's painting in the Ashmolean), the quarrel that followed was perhaps thought to be an unsuitable subject – an undignified display of familial discord – and lacking in graphic potential.

Christ disputing with the Doctors in the Temple

probably about 1520-5

Lodovico Mazzolino (c.1480–c.1530)

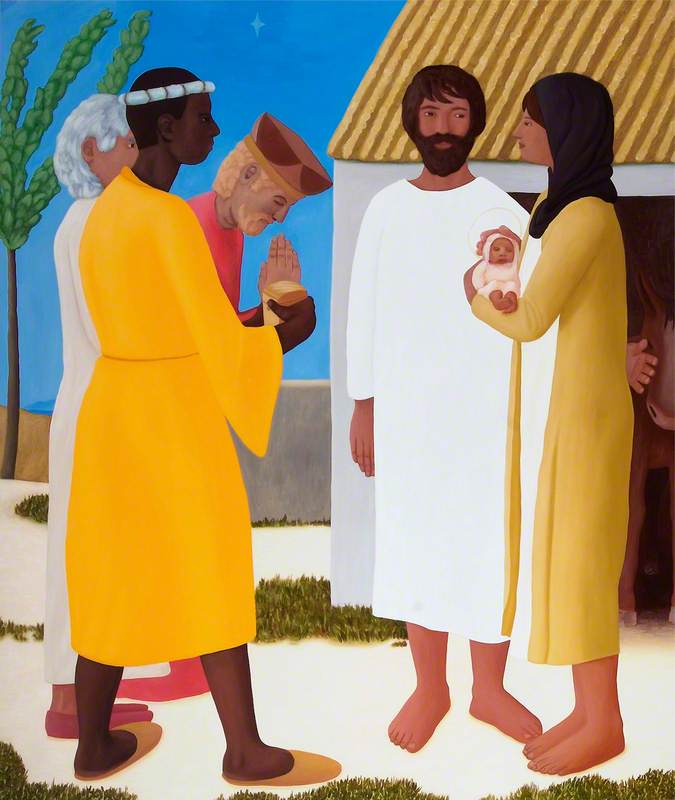

In Lodovico Mazzolino's crowded view of Christ in the temple, Mary and Joseph are seen in the group to the right. Having discovered Christ, Mary's relief has been replaced by dreamy pride at her son's rhetorical performance, and she appears lost in meditation.

The title sometimes used for Simone's painting, The Holy Family, might seem more appropriate, given the decontextualised image of the three family members. Simone's representation of the row requires no setting or scenery – all we see are the three figures against an unadorned field of gold. As a study of human behaviour, only the protagonists are necessary.

The Entombment of Christ (polyptych)

1335–1340, poplar wood by Simone Martini (c.1284–1344)

Simone stands out in his representation of intense emotion. In The Entombment, women bemoan the dead Christ, wailing and tearing at their hair – displays of grief that break with the dignified solemnity found in the work of other artists of his time. He developed the portrayal of emotion that Duccio, his teacher, had demonstrated in works such as The Crucifixion, now in the Manchester Art Gallery.

In Simone's picture, it is as though the protagonists of the great religious set pieces had stepped out of those emblematic scenes to display their ordinary natures. Christ Discovered surprises by its off-duty, unguarded quality. It's the shock of glimpsing Hamlet having a smoke backstage, or Juliet picking her nose.

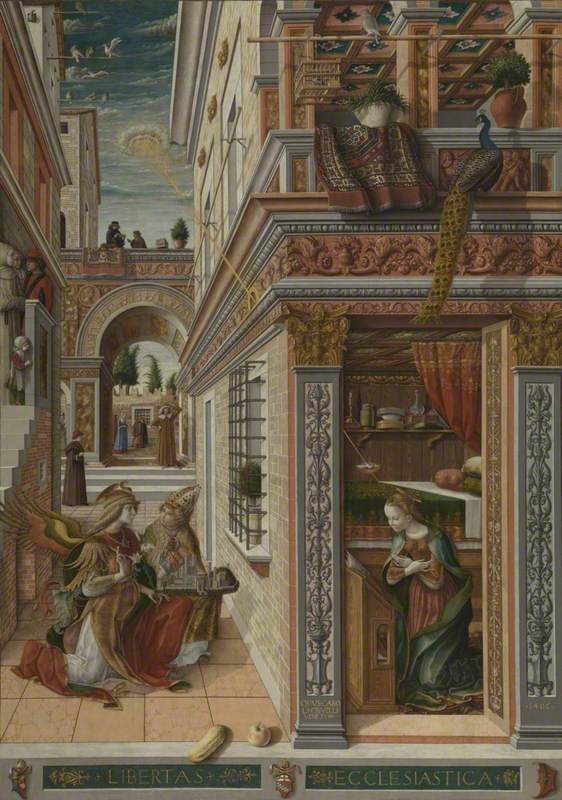

Annunciation with Saint Margaret and Saint Ansanus

1333, tempera on wood, gold background by Simone Martini (c.1284–1344) and Lippo Memmi (1291–1356)

But Simone was a master of surprises. His range as an artist was unparalleled among his contemporaries. He created the refined beauty of the Annunciation (1333) – considered his finest achievement – and the dynamic narrative imagery of the Blessed Agostino altarpiece (c.1328), which presents four of Agostino's miracles. In one scene, the saint swoops down like Superman to catch the slat that would have fatally injured a falling child. Having escaped harm, the boy is seen on his feet observing the action of Agostino in saving him.

Agostino Saves a Falling Child

detail from the Altarpiece of Blessed Agostino Novello, c.1328, tempera on wood by Simone Martini (c.1284–1344)

The power of Christ Discovered in the Temple rests in the finely judged portrayal of emotion. If considered separately, each face betrays its feelings with great naturalism and force. But taken together, in their triangulation, each makes its particular contribution to a distinctly fraught dynamic, reinforcing the tension.

Detail of 'Christ Discovered in the Temple'

1342, tempera on panel by Simone Martini (c.1284–1344)

This being the Holy Family, there are, of course, implications beyond the level of a family row. Christ has been made to submit to his earthly parents' wishes and scolded for his childish thoughtlessness. Yet it is hard to doubt Christ's awareness of his own importance and precocity. After all, he has just been dazzling the elders in the temple, who were 'amazed at his intelligence and the answers that he gave' (Luke 2:48). His folded arms and defiant expression say it all.

Although a young child, the stiffly standing Christ looks down on his mother, and it has been suggested that Simone deliberately wanted his Christ to appear to dominate a submissive Mary, illustrating the contrast between Christ's certitude and Mary's lack of understanding, and her unduly emotional response to his disappearance.

Andrew Martindale sums up the image as 'youthful obstinacy in a divine cause in the face of parental pressure.'

A further tension can be read in Joseph's unenviable position. He attempts to play the peacemaker, a vexed but conciliatory voice, appealing to Christ to respect his mother. But Joseph will always be a compromised figure: an earthly father and yet not a biological one, here contending with Christ's explanation that he had been absent in his true 'Father's house'. This gives what Martindale calls a 'subtle irony or pathos' to the depiction of Joseph, which is enhanced when we realise that this is the last mention of Joseph in the Bible. The elderly man would not survive to see his son reach adulthood, or so we must suppose.

As a study of human psychology from an era of refined and wistful restraint, Christ Discovered in the Temple is a bold performance. As an object to behold, it is an ingot of Tuscan light, a gilded wonder on the Mersey.

Adam Wattam, writer

Further reading

Don Denny, 'Simone Martini's Holy Family', Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, The University of Chicago Press, vol. 30, 1967

Timothy Hyman, Sienese Painting: The Art of a City-Republic, Thames and Hudson Ltd, 2003

Andrew Martindale, Simone Martini, Phaidon, 1988

Nathaniel Silver (ed.), Simone Martini in Orvieto, Yale University Press, 2022

.jpg)