In a piece for How to Spend It, writer and curator Lou Stoppard muses on the 'the delicious loneliness of swimming solo in some new place, among strangers.' She writes specifically about the luxury and 'solitary pleasure' of swimming in hotel pools; their exquisite designs and detachment from the hustle and bustle of the cities they are situated in. These places can often be frequented by a host of interesting characters reserving pool loungers with bestselling literary fiction. You would be hard-pressed to find as much peacocking at a public pool, but there is just as much eccentricity and beauty to be found.

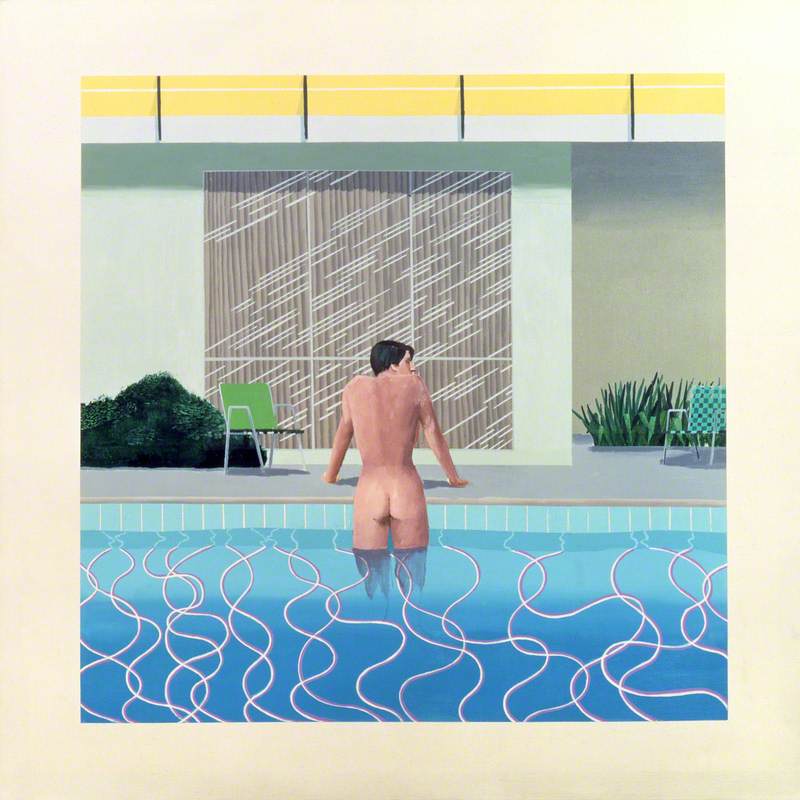

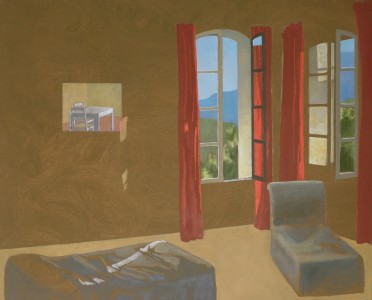

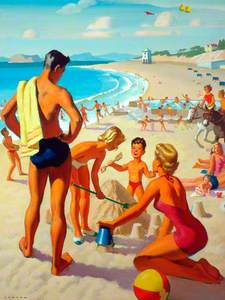

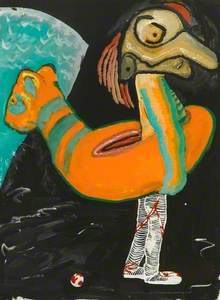

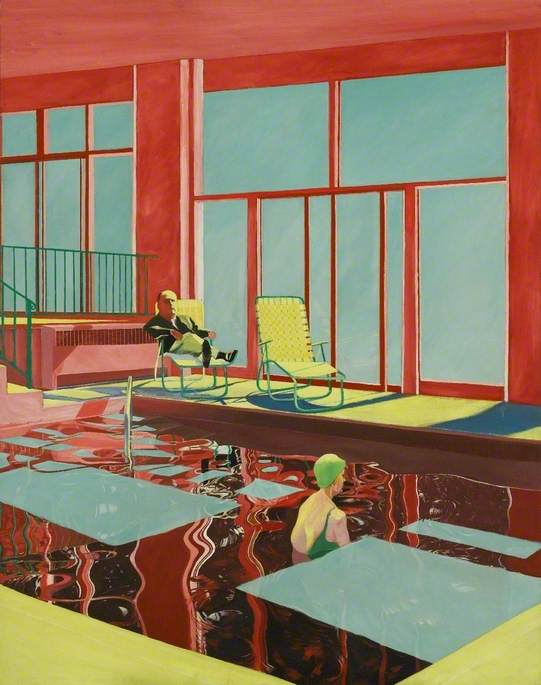

Man and Woman with Swimming Pool

1967

Neil Stokoe (b.1935)

The origins of spa towns and the British seaside resort roughly dates back to the eighteenth century. Characters in several of Jane Austen's novels talk longingly about 'the delight of the fresh-feeling breeze' and setting 'off in good time for the Pump Rooms'. However, the health benefits of sea bathing and fresh air were not made widely available to the masses until the expansion of the railway network during the Victorian era. Coastal towns across the country were soon filled with holidaymakers strolling along promenades, helping to turn them from small fishing communities into fashionable resorts.

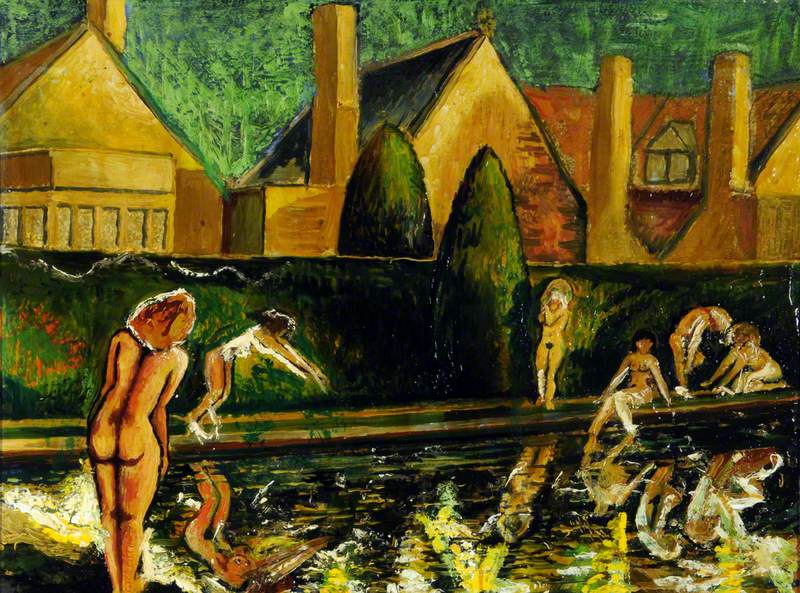

Back in industrialised towns and cities, the 1846 Baths and Washhouses Act and its encouragement of public washhouses would eventually lead to the establishment of municipal swimming baths. In a bid to combat the filth and crowded living conditions, these civic baths were a space for people to (ironically) have private baths, wash their clothes and learn to swim. By 1879, there were already 16 swimming clubs based in London baths alone.

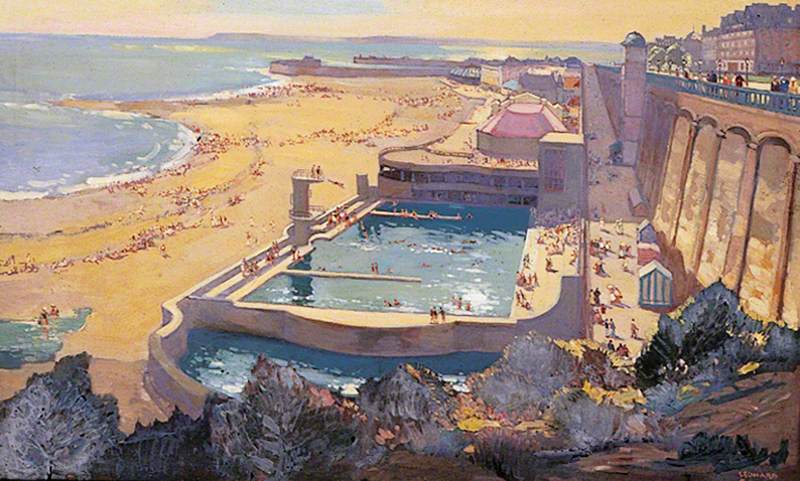

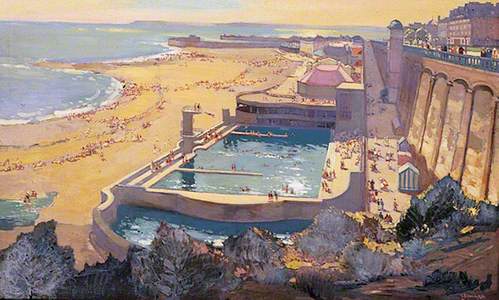

Railway companies serving seaside destinations began to introduce posters to advertise day trips and bank holiday weekends. By the 1920s and 1930s, outdoor swimming pools or 'lidos' (from the Italian for shore) were all the rage as the sun and sea could be enjoyed from a safe and comfortable distance in places like Plymouth and Penzance.

Burnham-on-Sea

(British Railways poster artwork) 1956

Alan Durman (1905–1963)

Their success dwindled following the Second World War, but Burnham-on-Sea (1956) by Alan Durman and Weston-super-Mare (1957) by Merville are both examples of lidos featured in post-war poster designs.

The colours are oversaturated, giving the impression that these scenes are set when the sun's at its highest in the sky. Figures are depicted with their arms jubilantly in the air, as if a giant beach ball has just been thrown or they are calling for someone's attention. The art deco diving board depicted in the latter was once the highest in all of Europe, while its open-air pool was the largest. Although attempts have been made to redevelop the pool, it was most recently the location of Banksy's art installation, Dismaland in 2015.

Lidos do not exist solely by the sea, but are just as cherished during sticky heatwaves in the city. The pool depicted in Summer (1933) by Miguel Mackinlay may not have as many lanes as London's Parliament Hill or Brockwell lido, but it certainly has as many swimmers making the most of their leisure time. The colours are more muted than those in the holiday poster designs, with several of the figures sitting around in quiet contemplation. There is a faint breeze in the air as the trees in the background can be seen blowing softly to the right. It is almost a snapshot of serenity before the diver jumps in or the two children cannonball from the slide. Rather than advertising the loud splashing at the seaside, Mackinlay's painting offers a calmer composition in which beach balls are yet to be thrown.

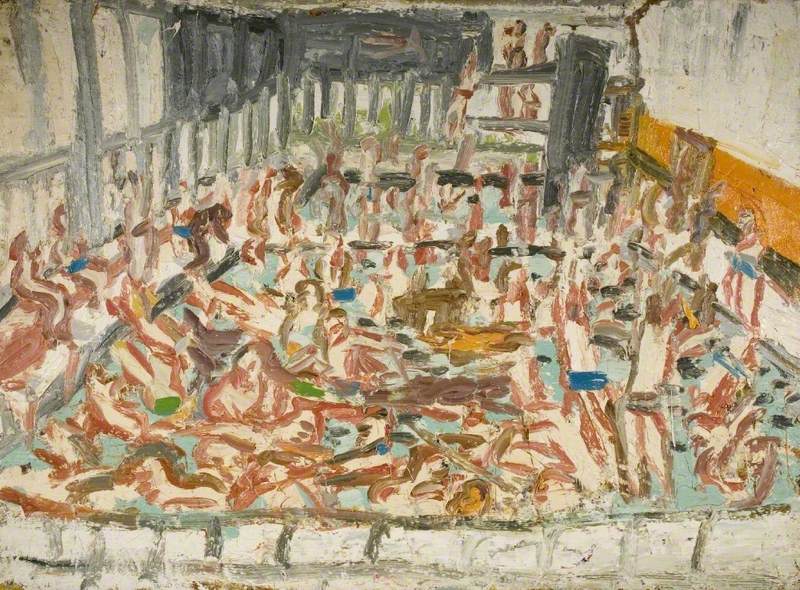

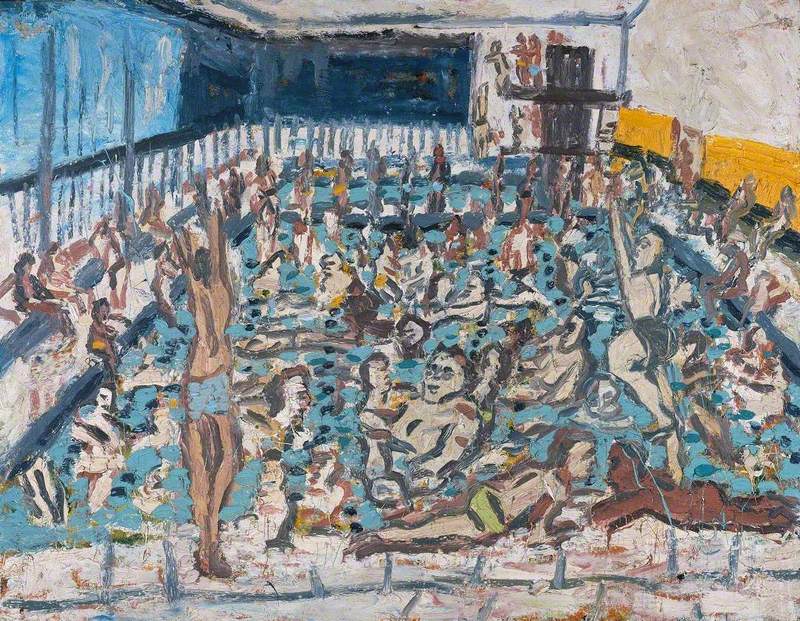

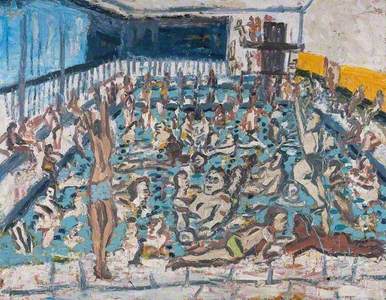

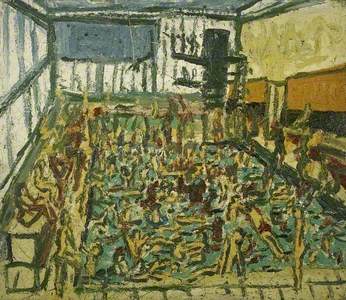

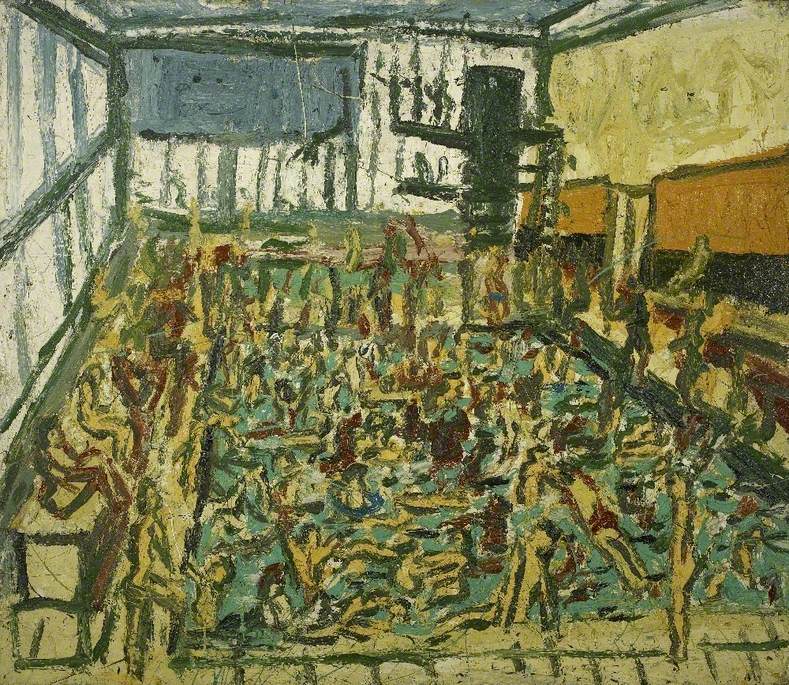

In contrast, a lifeguard's sharp whistle can almost be heard from looking at any of Leon Kossoff's three paintings: Children's Swimming Pool, Friday Evening (1970), Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon (1971) and Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn 1972.

Each painting shows the same indoor public pool dominated with children; arms and legs are everywhere as Kossoff captures the frenetic energy of the children splashing about in the water. The brushstrokes help generate a greater sense of movement and noise, regardless of which colour palette he uses.

Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn 1972

1972

Leon Kossoff (1926–2019)

Kossoff's works were based on a pool near his studio in Willesden, north-west London, where he took his son to swimming lessons. One wonders how often Kossoff himself was one of the onlooking parents always depicted on the left-hand side.

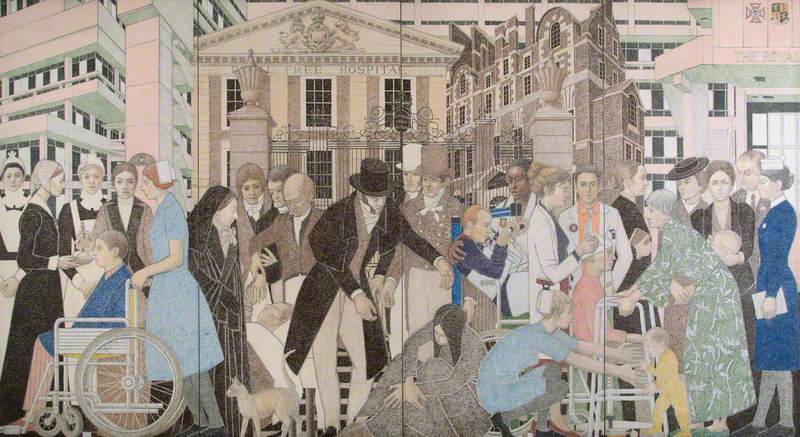

It is worth noting how many paintings of swimmers and swimming pools are part of hospital collections or initiatives like the Scottish charity Art in Healthcare. Artworks can provide a form of escapism during long stays and painful treatments, but they can also show different physical activities for patients to aspire towards when they are in better health.

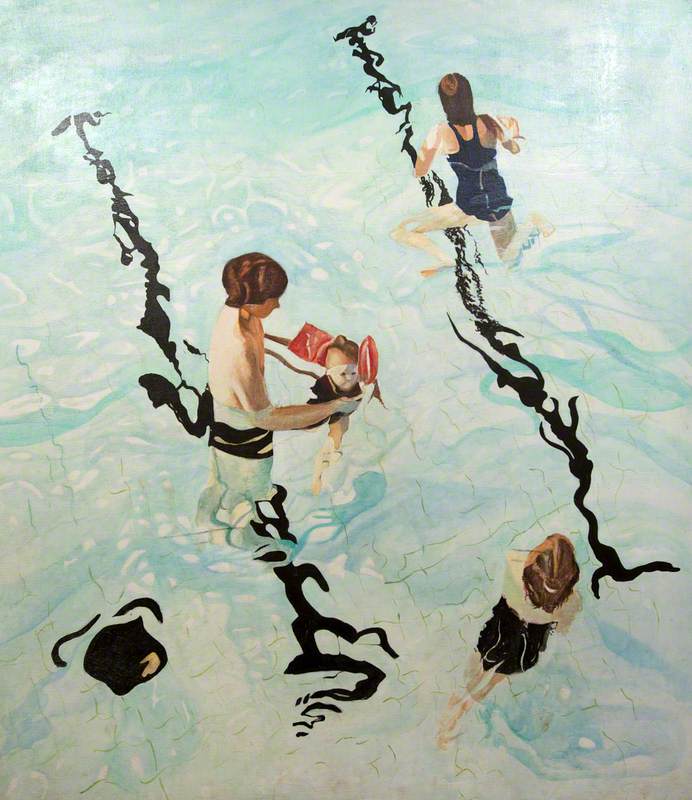

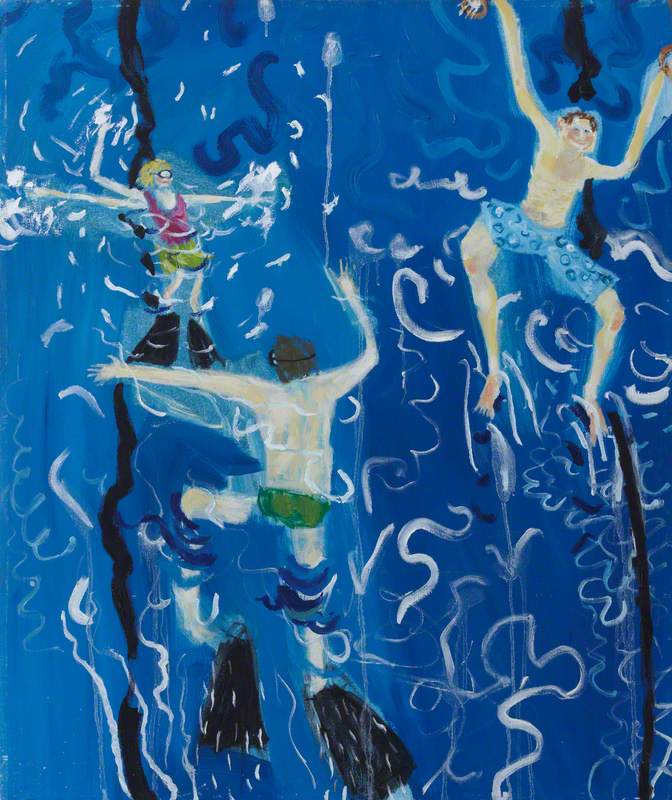

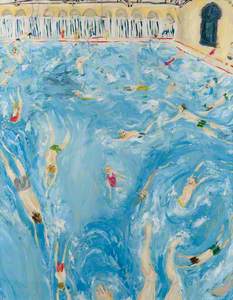

A number of Ivy Smith's paintings depict waiting rooms or hospital clinics and are held in hospital collections around the country. Swimmers (2007) is at Salisbury District Hospital, while Swimming Pool is at Northwick Park Hospital.

When discussing the former, which was commissioned for the Orthopaedics Department, Smith said:

'Swimming is a subject of great compositional potential. I feel the suggestion of weightlessness may be particularly welcome to people grounded by broken bones. The composition contrasts two energetic, splashing figures with the gracefulness and buoyancy of two swimmers reaching the edge of the pool. The figures form the main compositional structure of the work, but an important element of the image is the water, with its strong colour and its particularity as it flows over and around the figures.'

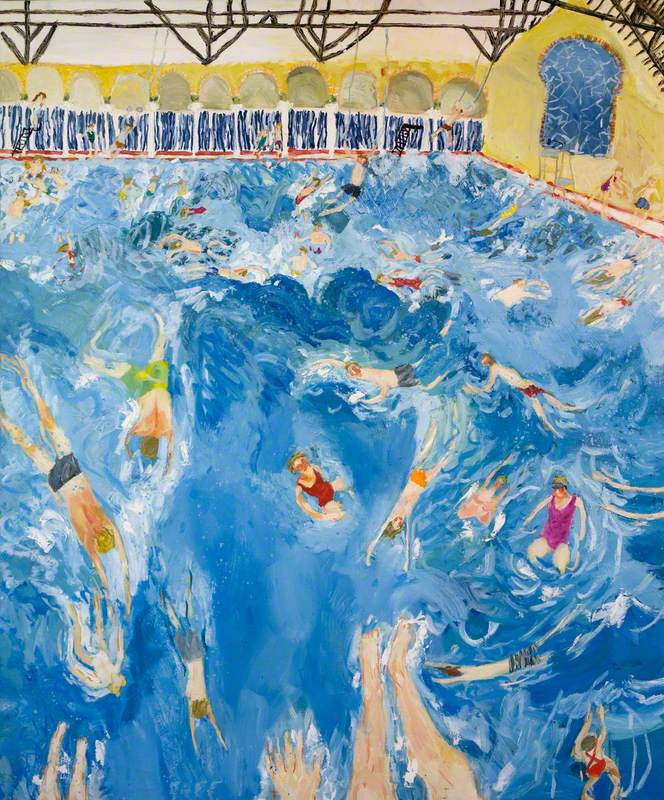

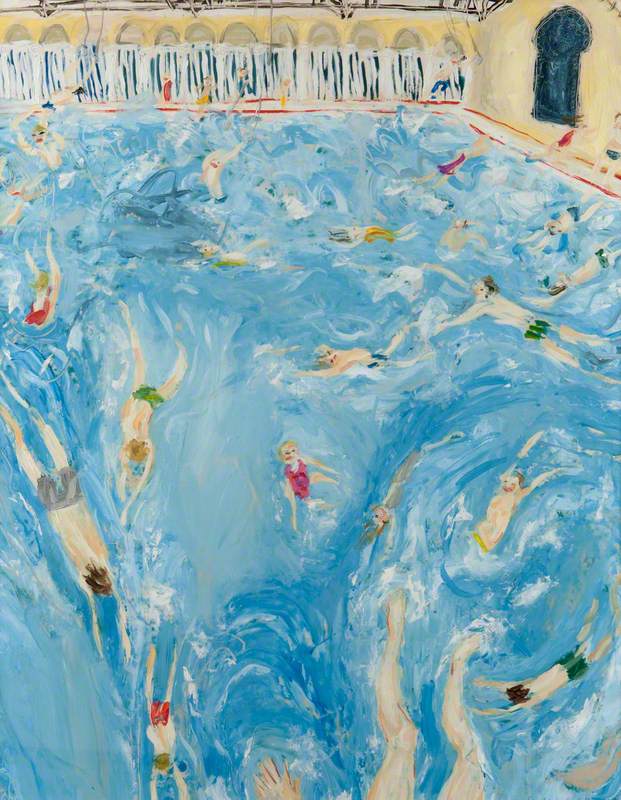

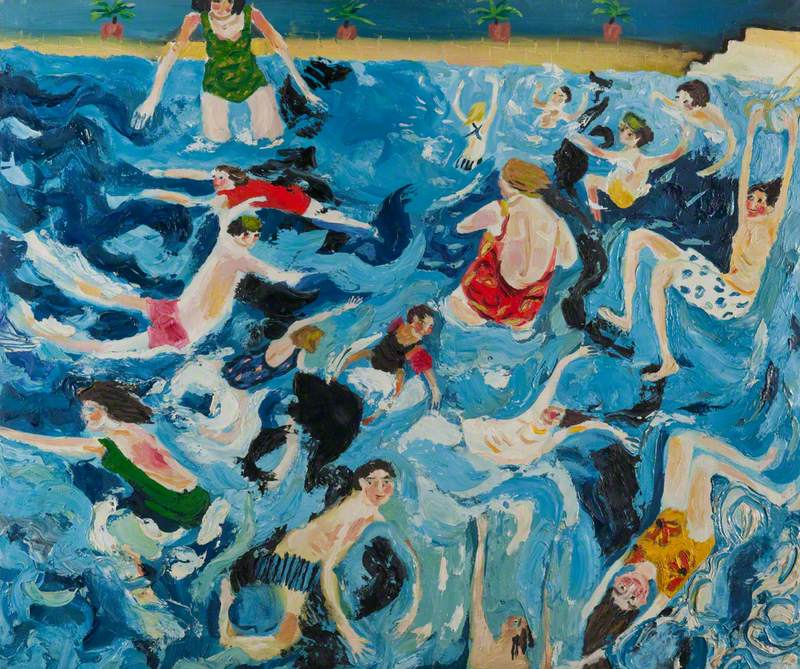

Emily Learmont also painted a series including swimmers and pools in 1992, which are all part of Art in Healthcare.

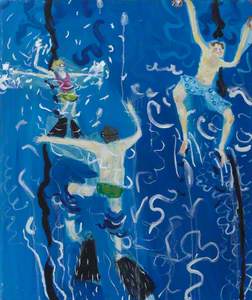

While Drumsheugh Swimming Pool and A Swimming Pool are very similar compositions from the perspective of someone looking across the swirling masses in the crystal-blue water, two paintings entitled Swimmers are much darker, with more detail given to the faces and features of those in the pool.

We almost get an aerial view of the swimmers, one looking up from their backstroke as they pass another wearing training fins.

Like Kossoff's work, Learmont captures the joy and vivacity of a public pool, but she also imbues the dreamlike weightlessness that can engulf a swimmer.

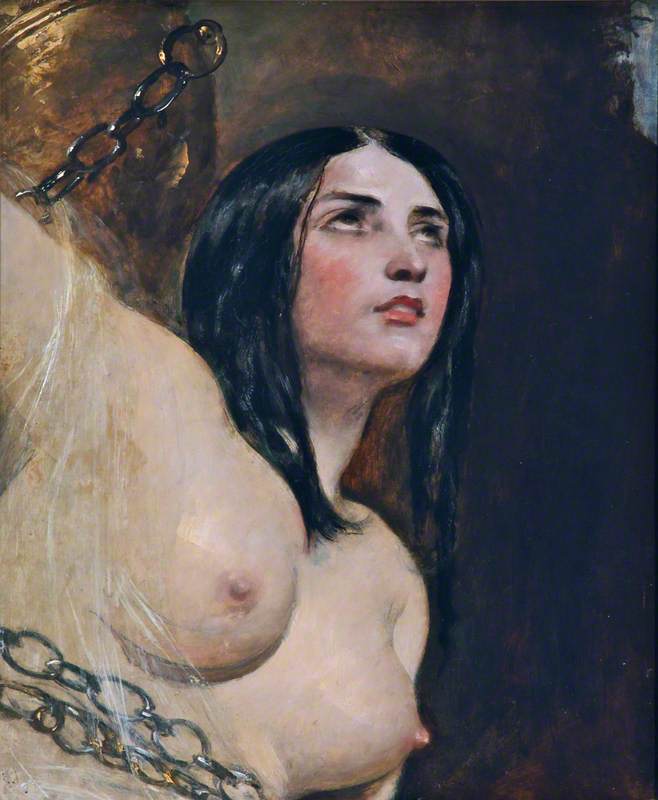

Lou Stoppard touches upon the difficulty of accurately recounting the unique sensation of swimming: 'The feel of being in water is so familiar, a return to a womb-like state, yet also so unusual, so exotic, so erotic, sometimes, that attempts to describe its multiplicity tend to fall short.'

In spite of its multifaceted nature, artists have long been attracted to painting pools and the swimmers plunging into them. The act of swimming can be restorative and invigorating for the solitary swimmer, yet it also has the power to unite when practised socially. The last few years have seen a revival in swimming at local pools and lidos, but also 'wild swimming' in the nippy waters of rivers and lakes.

Public baths continue to face funding cuts and maintenance issues, particularly those originating from the nineteenth century, and their significance in people's lives has never been more felt than their closure during the recent Covid-19 pandemic. As we gradually come out of lockdown, hungry for communal experiences and a return to some sort of normality, there will be nothing quite like jumping wildly into your local pool and breathing in the heady smell of chlorine.

Victoria Rodrigues O'Donnell, freelance writer