When the Imperial War Museum (IWM) recently refurbished their galleries, in time for the 100th anniversary of the First World War, it enabled them to hang their art collection properly. This included bringing excellent Nashes and Nevinsons out of storage, but one painting stands out in the fourth floor gallery of the museum. It’s by Stanley Spencer with the somewhat cumbersome but literal title: Travoys Arriving with Wounded at a Dressing Station at Smol, Macedonia, September 1916.

Travoys Arriving with Wounded at a Dressing Station at Smol, Macedonia, September 1916

1919

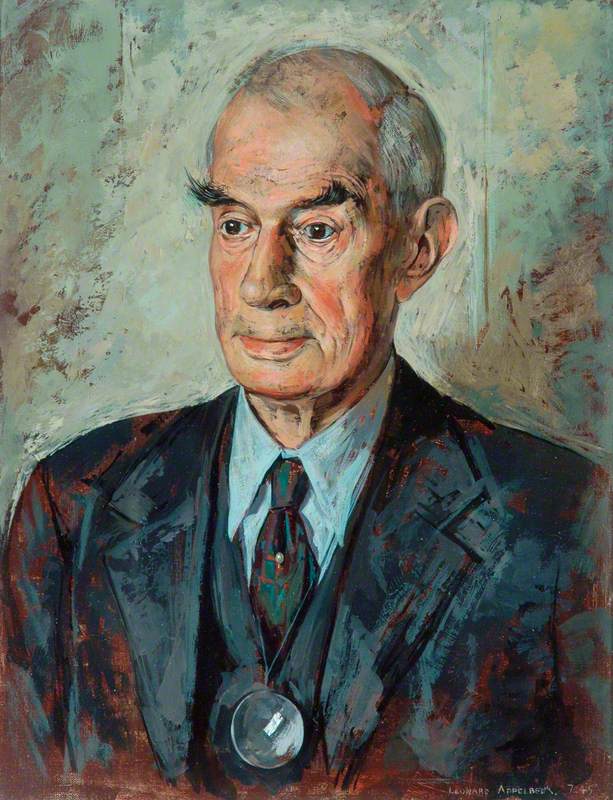

Stanley Spencer (1891–1959)

You can also access this image of a battlefield triage on the IWM website, but let me describe it. Four horse drawn stretchers are lined up in the foreground with wounded men lying on them, shrouded in blankets. Beyond the stretchers stand the horses, facing inwards, their stylised heads illuminated by a brightly lit scene depicting an operating theatre with a man on the table. The positioning of the stretchers draws your eye towards the heart of the picture, where this scene of life and death is being acted out. It is a great picture of a forgotten front in the conflict. And Spencer’s idiomatic style is instantly recognisable. This is the man who lived much of his life in the Berkshire village of Cookham and depicted many of its residents as characters in the New Testament (the events of which, in Spencer’s imagination, all took place in this small country location).

Spencer served in the war with the 68th Field Ambulance in the Balkans. He later wrote that 'the wounded passed through the dressing stations in a never ending stream'. He was deeply religious, as I’ve indicated, and he also wrote, 'I meant it not as a scene of horror but a scene of redemption'.

When you look at Spencer’s work you realise just how much Lucian Freud owes to him, much though devotees of Freud seem to resent this. And I’d maintain Spencer was the greater artist.

Sir Peter Bazalgette, Chair of Arts Council England