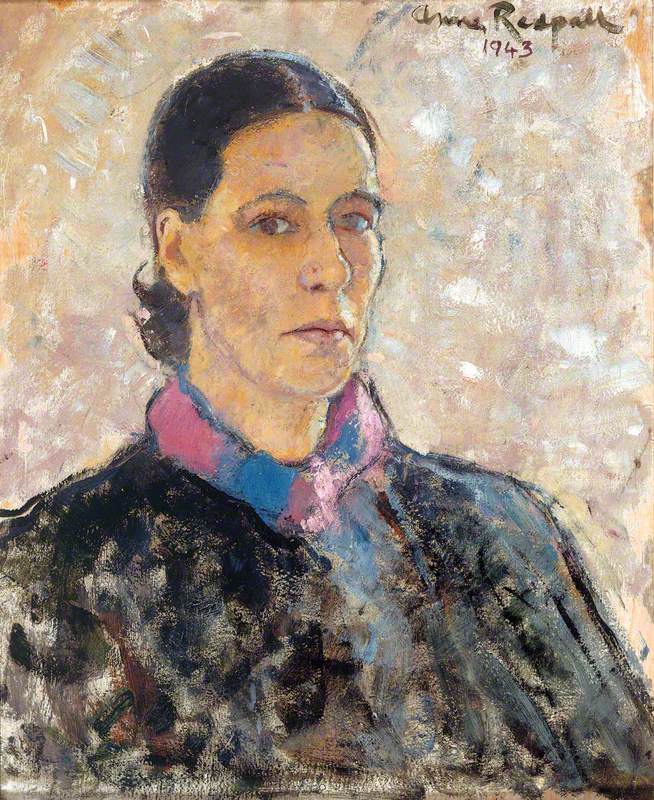

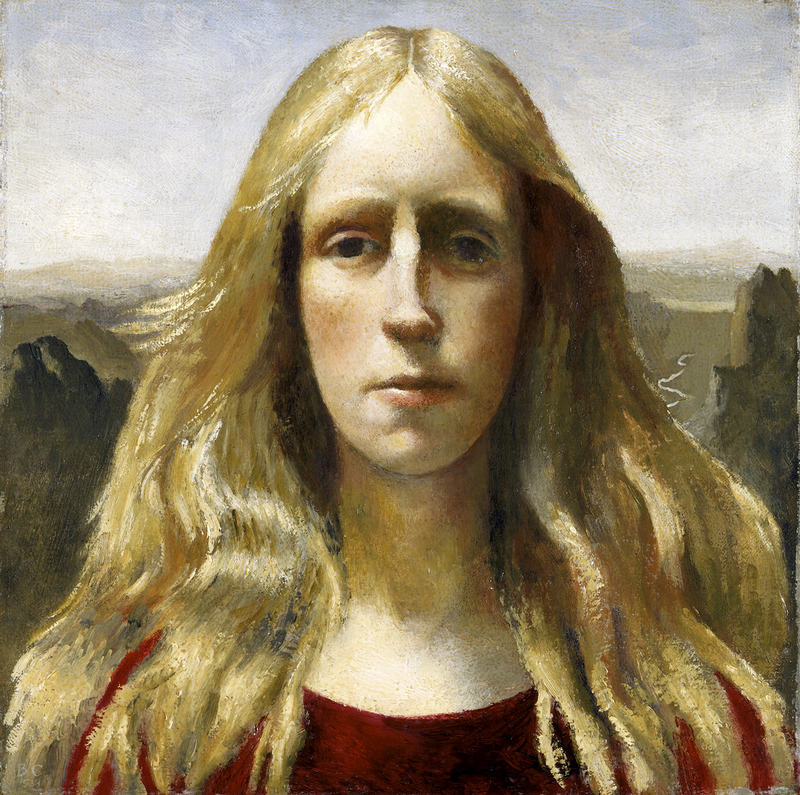

In 1926 Stella Steyn followed in the footsteps of many young modernists of her time and travelled to Paris to pursue her art training. She had been born in Dublin, the daughter of Jewish Lithuanian immigrants, and studied at the Metropolitan School of Art (now the National College of Art and Design).

When she decided to go to the French capital her painting tutor Patrick Tuohy (1894–1930) arranged for Steyn to have an introduction to James Joyce, whose portrait Tuohy had painted in 1924. A family acquaintance advised against Steyn seeing the writer who, she said, was a 'thorough ruffian' who 'had written a book no decent person would read.' But Steyn's mother allowed the meeting.

Mrs Steyn travelled with Stella and two of her daughter's friends so that the young woman could train at the Parisian studios, part of a generation of gifted young Irish women artists who went, that only a couple of years earlier had included Mainie Jellett (1897–1944) and Evie Hone (1894–1955). When Steyn met Joyce she thought the controversial writer appeared fragile, with his languid manner and eye patch.

She remembered an encounter with him: 'One late afternoon I had called for Lucia and was sitting waiting for her when he came into the room and, taking no notice of me, he went to the piano and with his head bowed over his hands, accompanying himself, he sang some melancholy Irish songs in a low, sad, voice. I said "You must miss Ireland." He replied, "I do." I said "Would you not like to go back?" He replied, "No. They jeer too much."' Despite his air of melancholy, though, Steyn remembered Joyce as a disconcerting figure and was afraid of him.

Joyce, however, liked Steyn's work enough to ask her to teach his daughter Lucia art, and the two women became friends. Lucia was talented – a professional dancer – but she was also troubled, and was eventually to be institutionalised. Although the Joyce family made efforts to downplay Lucia's importance in James Joyce's life and deter outside interest in her, to the extent, even, of destroying her letters, more recent research has suggested that Lucia Joyce was in fact a major influence on her father's novel Finnegan's Wake (1939). Her personality and even her speech patterns echo on its pages.

Stella Steyn herself appears as a character in the 2012 prize-winning graphic novel Dotter of her Father's Eyes by Mary M. Talbot and Bryan Talbot, about Lucia Joyce's fraught relationship with her parents.

365 reasons why comics are #1 art form, reason 362: Dotter Of Her Father's Eyes by Mary M. Talbot and Bryan Talbot pic.twitter.com/LQo3zn0Bsg

— Mitt Marney (@mittmarney) November 27, 2018

In the Talbots' book, the Joyces are dismissive of Lucia's ambitions (unlike the supportive Mrs Steyn), and Stella commiserates with Lucia over her mother's disapproval, saying, 'Oh dear, I expect you are too modern for her, Lucia.'

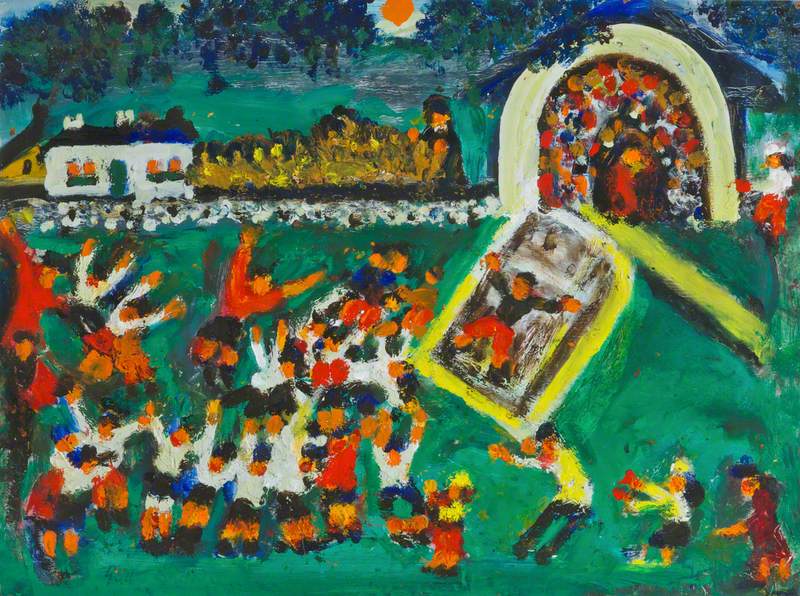

Steyn knew the Joyces during the years when Joyce was writing Finnegan's Wake, and he invited her to make illustrations for an instalment of the work in progress – Anna Livia Plurabelle – to appear in the experimental modernist magazine Transition.

Steyn accepted the commission, but when she read the excerpt she found it incomprehensible and was brave enough to tell the author so. 'Today I would have said that I understood him,' she wrote, 'but I am afraid at that age I did not lie, and so had to admit to him that I did not.' He advised her to respond instead to the musicality of the language and explained something of the characters, setting and plot, and the prints she made were published in 1929 in an edition with a cover by Kurt Schwitters (1887–1948).

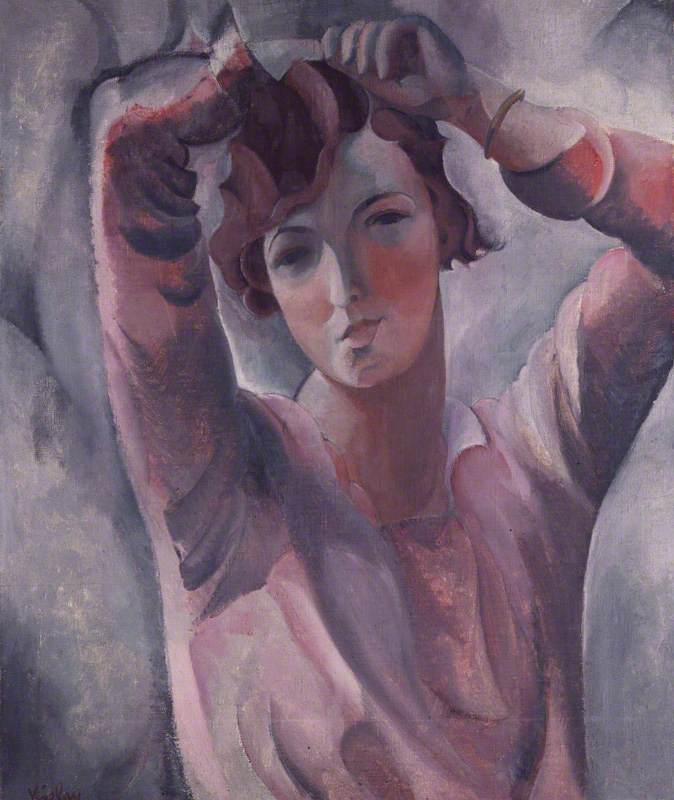

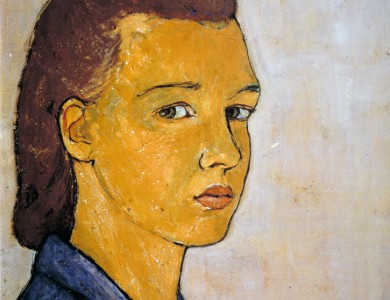

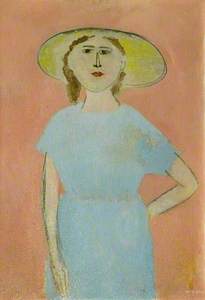

The linear fluidity of her drawings was also to shape her later paintings, such as Reclining Nude, in which the graphically outlined figure balances between two areas of colour. Transition also included work by Paul Klee (1879–1940), and there is a similarity in the ostensible naïvety of Steyn and Klee's art, a directness and vivacity that is in fact the product of skill married to daring, rather than untutored simplicity. Klee was to teach Steyn at the Bauhaus in the early 1930s.

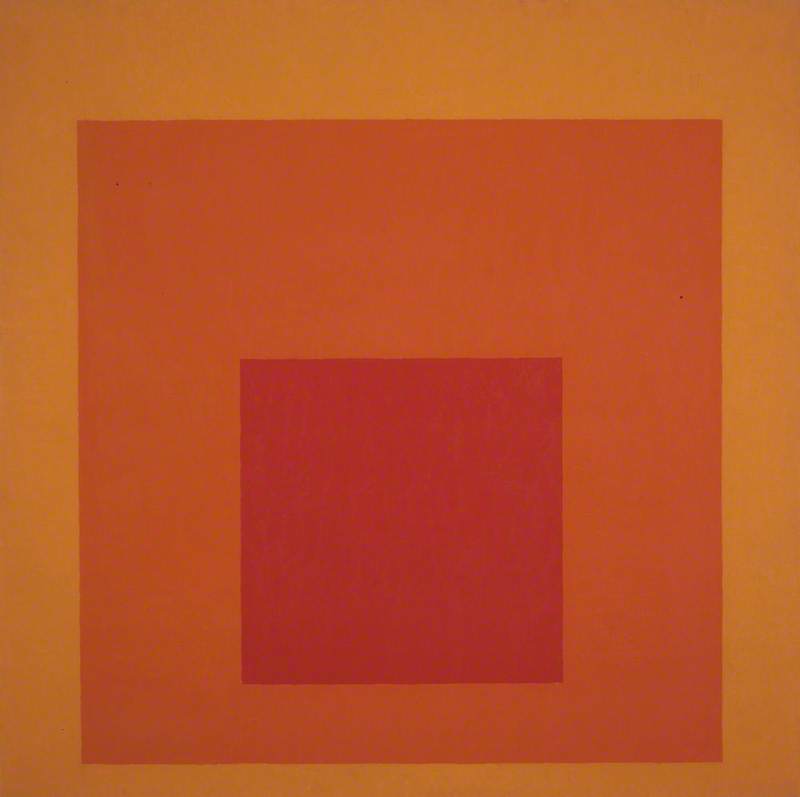

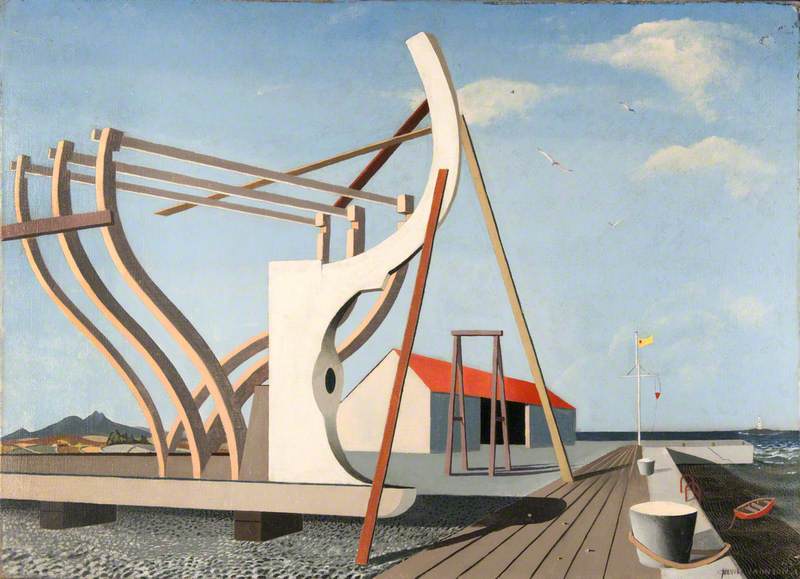

Steyn's relationship with the Bauhaus was complex. She trained there for one year, just before the school was closed by the Nazis, although she later remembered her stay 'was, for me, a false move, apart from the interest of the political scene in Germany at the time and the effect of turning me permanently to the painting which had its roots in tradition – which included Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, but did not include the contribution made by the Bauhaus or the École de Paris in its later stages.'

Apart from the wonderfully cool reference to the rise of Hitler, which Steyn, as a Jew, would have been particularly aware of and threatened by, her account does not allow for the influence that the school clearly had on her work. Some of her designs from her time at the Bauhaus survive; they appear to be exercises which the teacher Joost Schmidt created for his students in the printing and advertising workshops, in which single letters are offset with areas of pattern and empty space in a stripped-down palette of bright red, black and blue.

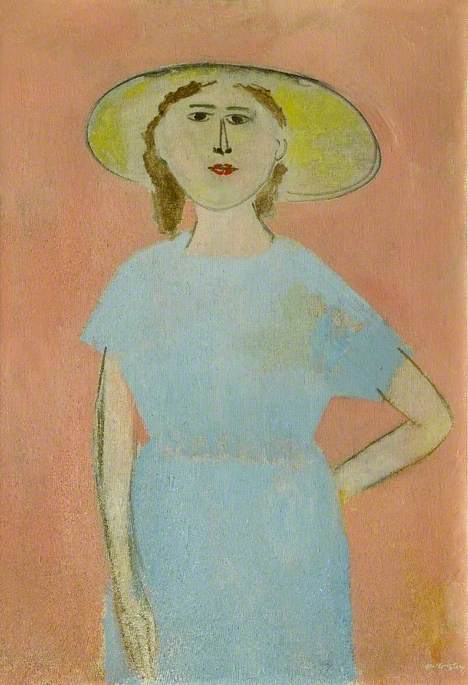

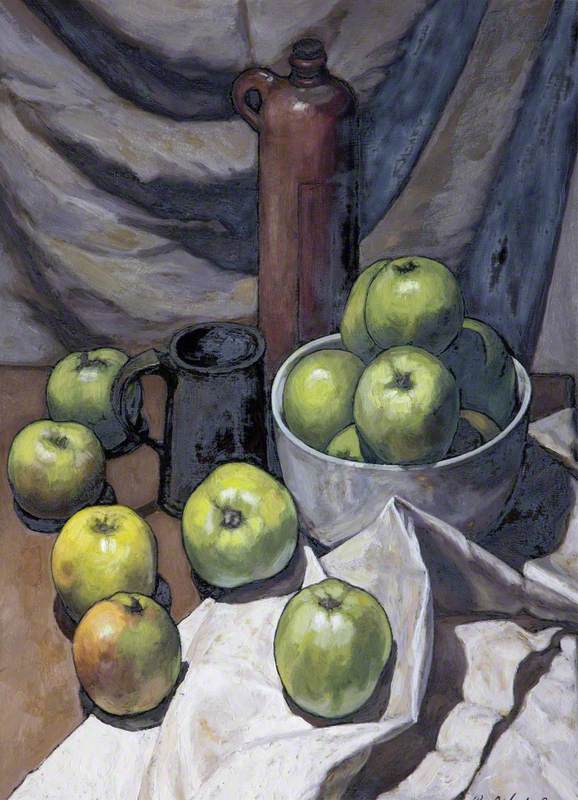

Steyn's emphatic use of flat colour in paintings such as Woman Seated at a Table often fills entire areas of canvas, and there is something off-kilter and therefore interesting to the eye about her sense of composition.

This surely has its precursors in the graphic inventiveness of Bauhaus productions, even if her loyalty to figuration, and the subject matter of portraits, nudes and flower pieces also allies her to the painters she had admired in Paris before she went on to the German art school: Maurice Utrillo (1883–1955), Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920), Jules Pascin (1885–1930) and Chaim Soutine (1893–1943).

Steyn had a one-woman exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in 1951, and three years later a joint show was held there with Ivon Hitchens (1893–1979).

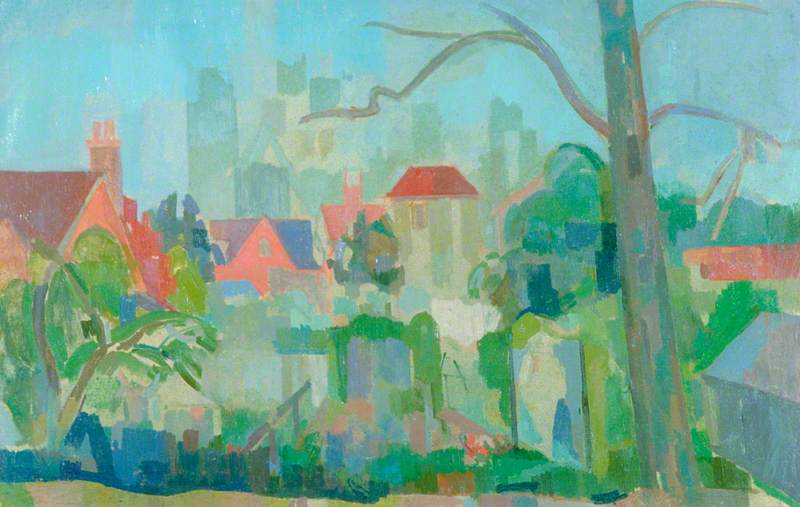

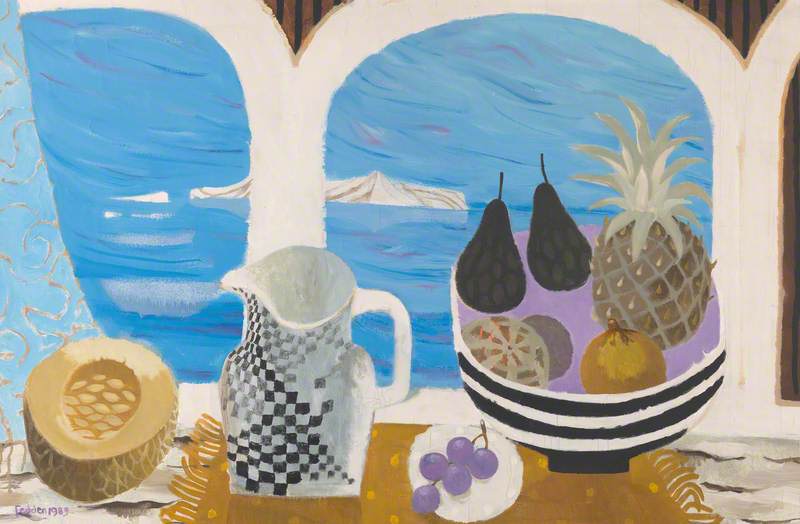

Steyn's Townscene, with its Cézanne-esque blocky structure, and pure, almost luminous colour – terracotta, blue, green – suggests what an interesting pairing this must have been. But, like so many women artists of her time, Steyn disappeared from the public eye for years, until the 1990s, when exhibitions of her work were held at the Gorry Gallery, Dublin, and the Belgrave Gallery, London.

Alicia Foster, curator