Content warning: this story contains an image of deceased people/body parts that some may find disturbing.

The indigenous people of New Zealand, known as the Māori, were pioneers in the art of tattooing. They created complex, intricate designs which were unique and distinctively Māori. British arrival in the islands and subsequent colonisation changed Māori society forever – and began a steady decline in traditional tattooing. This was in part due to the newcomers' fascination with Māori tattoos, which led to a morbid trade in tattooed, decapitated heads. Here's a look at an ancient Māori tradition, as told through art.

An ancient tradition

Tā moko were traditional tattoos worn by both men and women and were prevalent in Māori society before European arrival. While moko could adorn many different parts of the body, the most significant mokos were tattooed onto the face. These facial tattoos were reserved for people of high ranking, such as chiefs, and were symbols of their mana or prestige.

The process of receiving one of these full facial tattoos was no mean feat. A form of scarification, traditional tā moko were literally carved into the skin, much like carving into wood. The tohunga, a skilled tattoo artist, used a mallet to tap the designs into the skin with a chisel. Pigment, made from a mixture of charcoal, ash and oil, would then be applied to create the tattoo. Receiving a tā moko was considered sacred, and there were many traditions and taboos involved.

Māori chief, Patarangukai

c.1882, lantern slide by J. S. Powell

The art and cultural significance of tā moko

Tradition dictated that tā moko designs be carefully planned after discussions between the tohunga and the subject. Each moko was thus unique and depicted the personality and history of the wearer. Every part held meaning. In general, the forehead design represented a person's status, the cheeks indicated the work he did and the temples, his marital status. In addition, the moko could depict a man's genealogy, his tribe, sub-tribe and his mana. Like a passport or ID card, a facial moko was a way of showing everyone who you are and what you stood for.

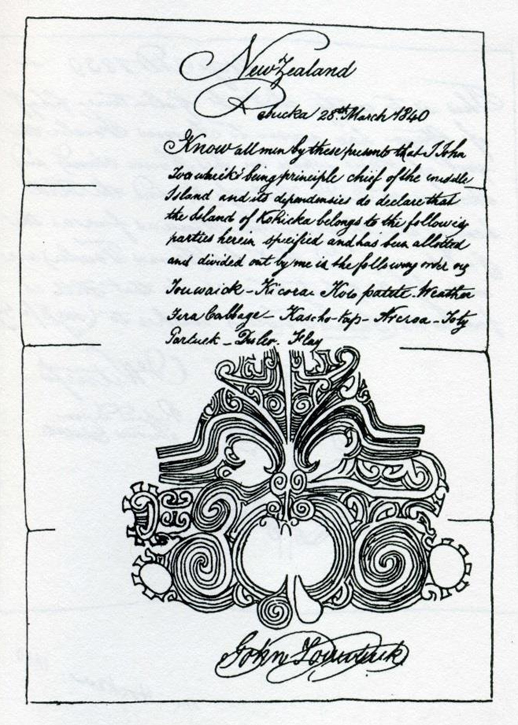

A tā moko was, in essence, a deeply personal and symbolic marker of identity. Facial mokos were so intertwined with identity that they were used as signatures by some Māori chiefs when signing agreements, such as land deeds, with the British. The image below depicts a land grant signed in 1840 by Tuawhaiki, a Māori chief from the Otago region.

Moko signature on a deed

published in 'Moko or Maori Tattooing' by Horatio Gordon Robley, 1896

As can be seen, his moko has been carefully recreated in incredible detail. Tuawhaiki drew, in essence, his own self portrait as his signature. This shows how intimately the chief was connected to his moko. It was a physical symbol of himself and his connection to his tribe, his ancestors and the mana of his people.

Lindauer and Goldie's Māori portraits

European immigrants to New Zealand also produced fascinating artworks of Māori people. One of these immigrants was a Czech artist named Gottfried Lindauer, who painted many well-known portraits of Māori from the late nineteenth to early twentieth century. Lindauer's portraits were unique in that many were commissioned by Māori themselves, on their own terms. Today, his portraits of Māori men and women are still considered treasures by their descendants.

In Lindauer's portrait of a chief named Ngairo Rakai Hikuroa from the North Island of New Zealand, the artist has depicted the intricacies and detail of Hikuroa's tā moko clearly. Like all mokos, his is highly symbolic but it also depicts some familiar motifs found in Māori art such as the spiral shape, representing the silver fern frond. This shape can mean growth, strength or peace, and its placement accentuates the natural shape of the face.

This portrait also shows how Māori designs make clever use of negative space to further enhance the moko. Hikuroa wears traditional attire, such as the korowai cloak and his shark tooth earring.

Māori women also had facial tattoos called moko kauae, which were only on the chin and lips, as we see in Lindauer's portrait of Ana Rupene, shown carrying her daughter, Huria, on her back.

Charles Goldie was another European artist who made his name painting Māori portraits, especially portraits of elderly chiefs, between 1900 and 1940. Goldie was a master at creating technically brilliant, almost photographic works.

Allee Same Te Pakeha (A Good Joke) – Te Aho Te Rangi Wharepu (1811–1910) in European Costume

1905

Charles Frederick Goldie

His portrait of Te Aho Rangi Wharepu, a Ngati Mahuta chief, is captivating. It's so lifelike that one almost can't help but smile back at Te Aho's good-natured grin.

A close look at the chief's facial moko enables viewers to see the tattoo in acute detail – the grooves cut into the skin much deeper than a modern tattoo. Goldie's renderings of traditional tā moko are still considered today to be the best representation, photographic or otherwise, of what a chisel-carved moko really looked like.

Te Aho Te Rangi Wharepu (1811–1910)

1907

Charles Frederick Goldie (1870–1947)

Goldie's portraits offer a significant contrast to Lindauer's. In Lindauer's portraits, his subjects are posed classically and portrayed in a dignified, regal manner. Goldie's portraits, on the other hand, often portray his elderly subjects as downcast and weary in a variety of postures: sometimes sitting down or leaning on something, for example.

Interestingly, Goldie also included environmental backgrounds in some of his work, depicting his subjects in traditional settings such as Māori meeting houses. Lindauer preferred a more formal background featuring a single colour or nature scene.

A Māori Chieftainess (Harata Rewiri Tarapata, 1831–1913)

1906

Charles Frederick Goldie (1870–1947)

Goldie's portraits have also attracted much more controversy and criticism than Lindauers', both during his time and to this day. Contemporary critics accuse Goldie's work of being condescending and even racist – perpetuating a narrow perception of Māori as a dying race.

While the two artists have their differences, their portraits have one important thing in common – they are cherished by the Māori people, who believe that the portraits contain the wairua or spirit of their ancestors. Not to mention, they are important records of the last generation of chiefs with chisel-carved facial mokos.

Wood carving and tattooing: complementary arts

Designs used in tattooing were also integrated into wood carving. The Māori were master woodcarvers, and these artworks were integrated into everyday life, adorning meeting houses and canoes. As we saw with mokos, Māori carvings and art were rarely purely decorative – instead, they told stories and thus acted as important repositories of knowledge.

Typically, carvings such as this early twentieth-century example represent a specific person, often an important ancestor or a character in a legend. This figure is a man and probably a warrior of high rank due to his mokos and the weapon he is holding. His eyes are made from abalone shells, giving them an iridescent and life-like quality. His face is covered in the swirling patterns of tā moko and his expression is staunch. Perhaps this figure was built to stand guard outside a house or entrance – but without knowing the original context it is impossible to know for sure.

The impact of colonisation on tā moko

The arrival of James Cook to New Zealand in 1769 heralded a new era of European colonisation, which had a devastating impact on the Māori people and traditions such as tā moko. Europeans, and missionaries in particular, disapproved of mokos and discouraged the practice. Nevertheless, many were fascinated by Māori facial tattoos.

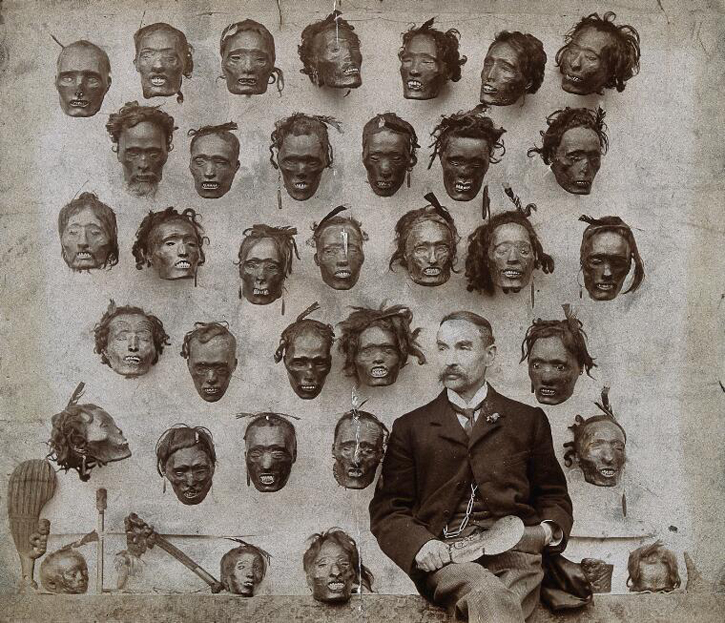

Horatio Robley, seated with his collection of severed heads

1895, photograph by Henry Stevens (1843–1925)

Among the 'souvenirs' brought back to England by Cook was a tattooed, decapitated, preserved Māori head called a mokomakai. This sparked a gruesome and lucrative decades-long trade in heads. Mokomakai were in high demand in Europe, where they sold as collector's items and curios to the wealthy. In New Zealand, the head trading caused bloody inter-tribal conflict, with the Māori trading tattooed heads for valuable muskets. Tribes began tattooing the faces of prisoners or slaves in order to kill them and exchange their heads with traders.

A positive future

Due to colonisation, missionary influence and the morbid trade in heads, the cultural tradition of tā moko dwindled and almost disappeared. Today, however, this has changed. Māori are once again proud of their cultural heritage and traditions. Many choose to get their own traditional tattoos and facial mokos are making a comeback. Now, modern Māori tattooists and artists take pride in perpetuating and evolving the artistic traditions started by their ancestors so long ago.

The Marton Moai: Ko Tutira Kei Ahunehenehe (The Lookout on the Platform of the Ancients)

2008

George Nuku, David Gross

One prominent contemporary Māori artist is George Nuku, whose artworks combining modernity and tradition are an exciting indicator of the future of Māori art.

Tiare Tuuhia, writer