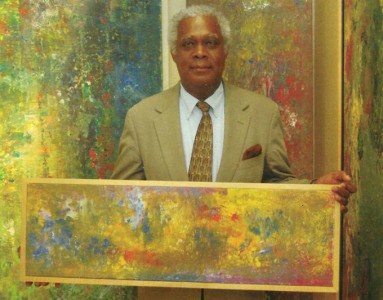

Dominican-born Tam Joseph is multi-pronged when it comes to art; boxing him into a single narrative or style is a losing game. The remarkable British artist invited me up to his North London studio in Blackhorse Lane.

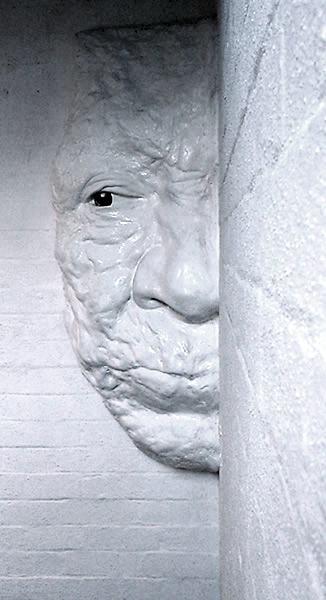

At the building’s door lies his subdued creation of a grass-covered earth-figure, face down in an anonymous slump (Rough Sleeper, 2017). He explains that it represents the homeless. He tells me that he once worked with the charity Crisis and says that because art demands such complete focus, it can help anchor a troubled mind. I ascend the stairs to confront the plaster and screed part-face of his mother-in-law, large and lined and stricken with Alzheimer’s.

This Wall is Old and in Need of Care

2005, chicken wire, scrim & plaster of Paris by Tam Joseph (b.1947)

On the wall opposite the studio is a piece of alchemy – rows of golden pomegranate shells, sculpted by birds, hardened by time and arranged by Tam Joseph.

Nature Morte

2016, pomegranate husks & steel nails, 35 x 120cm by Tam Joseph (b.1947)

It is immediately clear, if I ever doubted it: his vision is unburdened by any 'ism'. No one is going to co-opt him into any one movement or manoeuvre him into any one chronicle: 'Not everyone gets me and my work. I’m not really built to go where people want to push me. Don’t bother with pleasing everyone is my advice.'

The studio is like the man: slim, no-nonsense and singular. Pictures of Jimi Hendrix, Miles Davis and Billie Holiday are among his father’s tools, hanging workmanlike on the wall: 'I love tools, lots of tools and I like working with my hands. Doing and making gives me deep pleasure. I’m never lonely. These are my fraternity', he says, pointing to row upon row of paintings hidden in brown paper: 'I like having my work around me.' Hoping he’ll unwrap the paintings, I try to unwrap the man.

For Tam, you need a way of seeing and, most importantly, a powerful and efficient skill set to manifest everything in your head.

Tam Joseph was eight when he left the island of Dominica on an ocean-liner bound for Britain. It was the mid-1950s. Paper and pencils were scarce around the house growing up but, with perfect self-direction, his artistic formation went ahead anyway. Animation claimed him early and, at the age of 14, he was making flicker books from old laundrette counterfoil stubs. The clear advice from John Halas (renowned animator of Animal Farm, 1954) was: 'go to art school'. As a young boy, Tam found his early teachers in library books about the Old Masters; his early life-drawing cohorts at the 'Islington Art Circle' were all aged 60 plus.

'I couldn’t have gone to a better school', he says. 'Drawing is a great leveller and I belong anywhere where people like drawing.'

These early classes sucked him into fine art and eventually led to Central School of Art and Design in 1966, followed by a BA course at the Slade School of Fine Art, but he left the Slade before completing the BA and worked as a painter and tracer in Soho Square on Yellow Submarine: effortless fun. He quit before work on the film ended, wanderlust taking him through Europe and eventually throwing him up in Rishikesh, India in 1968. After returning to England a year and a half later, a brief spell as a postman followed before he entered the London College of Printing in 1973 to study typographic design. Three years later he graduated and moved on to work as layout artist and graphic designer for Africa and West Africa magazines, also designing the occasional album jacket.

Images, millions of them, have been Tam Joseph’s constant companions since childhood – trees, clouds, and stones. He has siphoned up Rembrandt, Michelangelo, Caravaggio, Hokusai, Picasso, Matisse, and Soutine – painters who make difficult techniques look easy. It is always the ‘how’ more than the ‘what’ that places him in front of the same pictures, in the same museums: ‘Painting is about looking and interpreting and interpreting and looking again. It’s about scraping back to go forward.’

This last point is important, he explains. Artists don’t have time to muck about. It is all about integrity and giving a hundred percent of your will before arriving at the hidden plateau.

Of course, a little money is good. Good-quality artist’s materials have never come cheap, and he is quick to point out what he could do in a bigger studio – but he will not be held back.

Aptitude is not all. You have to face the difficulties head-on. But it’s not a chore if you love it.

‘Lots of things enter my mind all the time. I’m an avid collector but I collect mainly by looking and connecting. I have literally galaxies of thoughts that can slip away if I don’t record them quickly with a sketch, a title in the notepad or a photo on my phone. These are my memory joggers. I get bits of wood out of skips and I think, one day, I might be able to use this in the work. You never know. I’m a gatherer and I’m on the ball. I have to be because you get fewer ideas if you don’t act instantly and record. That’s how it works, at least for me.’

He talks about materials. Plaster, clay, papier-mâché, iron-filings, wood, linen, metal, oil, acrylic are all mentioned in minutes and have all found their way into his paintings and sculptures. Picasso saw a gorilla’s head in a toy car, and a bull’s head in a bicycle saddle and a pair of handlebars. For Tam, you need a way of seeing and, most importantly, a powerful and efficient skill set to manifest everything in your head.

‘And you have to go at it… Aptitude is not all. You have to face the difficulties head-on. But it’s not a chore if you love it. I have an exacting hand and my body understands the potential of each tool at a deep level’. He picks up a pencil, with such grace, to illustrate the way a different pressure, a different grip, can affect the flow and line of the lead.

Tam Joseph has exhibited widely. Newly Orion, The Sterling Smith Gallery, The Whitechapel Art Gallery, The Gallery HD Nick in Aubais, The Gallerie Salamandre in France, Wolverhampton Art Gallery, The ICA, The Perez Museum of Art and the Queens Museum of Art in the United States have all come calling. His paintings have travelled up and down the UK and America. The internet gives access to much-loved luminaries like The Spirit of the Carnival (1982), School Report (1980) and The Flying Doctor (1994).

I wait as the artist rises to unwrap his recent work.

Walking the Dog (2018) in oil and acrylic shows the back view of a substantial black matron in her rosy-ironed best, stepping out into the black night. On her right are constellations; bright Sirius, the Dog Star, lurks in Canis Major. Tam explains he has seen the woman in the street; he has seen the dormant magic in the everyday. The painting points to his interest in astronomy, science fiction and the African within him.

Walking the Dog

2018, acrylic/oil on canvas, 95 x 120 cm by Tam Joseph (b.1947)

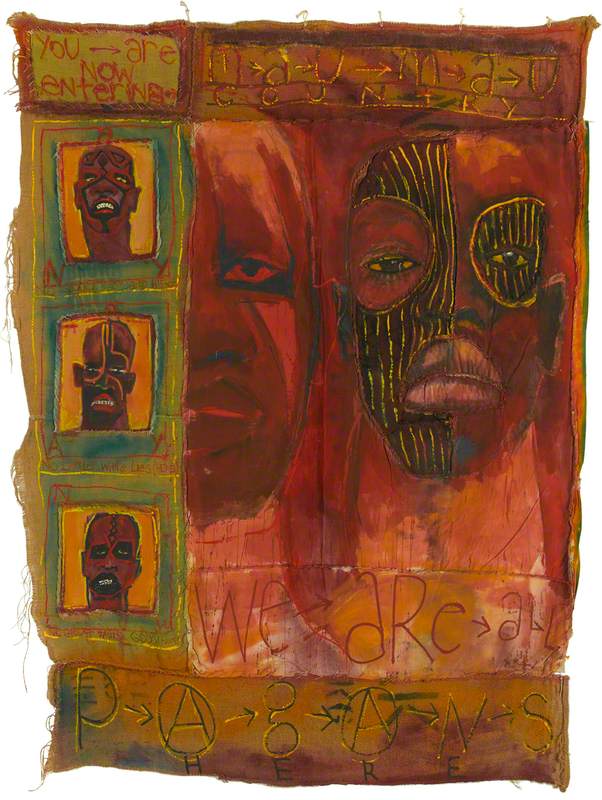

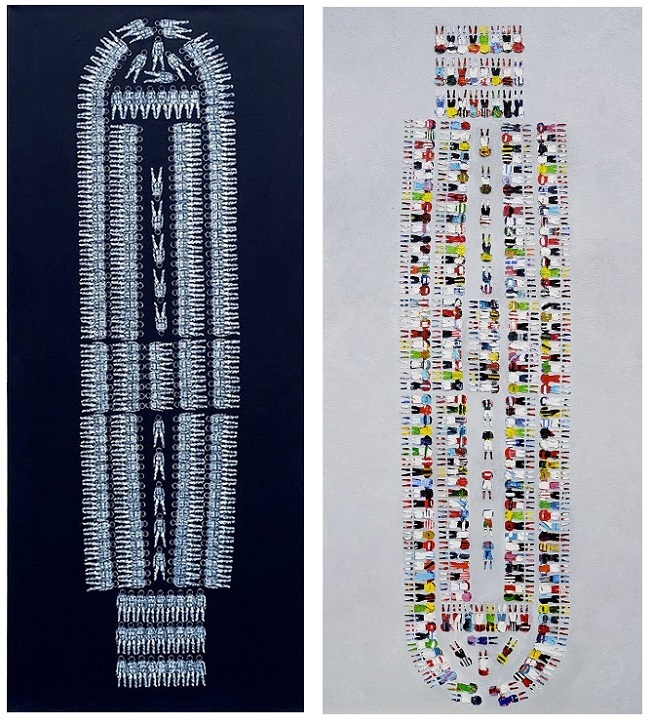

Blueprint for the Colonisation of the Other Planets (2017) and its sister piece, Team Building in the Early Stages (2017) both shock. The first is a response to Stephen Hawking’s idea of human survival through the commandeering of astronomical bodies. Men in spacesuits lie face-up in orderly formation, encased in the outline of a slave ship. The sister piece replicates the first in structure but, this time, the ship’s occupants are in varying football attire: ‘There is a black man in every football team in the world, all descendants of slaves.’ The socio-political commentary is clear in the paintings and in Tam’s remark.

Two artworks by Tam Joseph (b.1947)

Left: 'Blueprint Plan for the Colonisation of other Planets', 2017, acrylic on canvas, 95 x 200 cm. Right: 'Team Building in the Early Stages', 2017, oil on canvas, 95 x 200 cm.

The Extraordinary Qualities of the Gadarene Swine (2018) is unwrapped last. The Biblical allusion may be opaque to some, but there is no holding back a chuckle at the sight of a group of pigs tumbling trustingly into the waiting water; Tam personally visited the Irish Cliffs of Moher from which his acrobatic pigs dive in an incredible range of perfectly executed somersaults and twists.

The Extraordinary Qualities of the Gaderene Swine

2018, oil on canvas, 95 x 200 cm by Tam Joseph (b.1947)

‘Right formation, wrong direction’, he muses drily on the pigs’ performance. And I leave the studio musing. When it comes to Tam Joseph the artist, he is always right on both counts.

Catherine Farren, historian and former actor