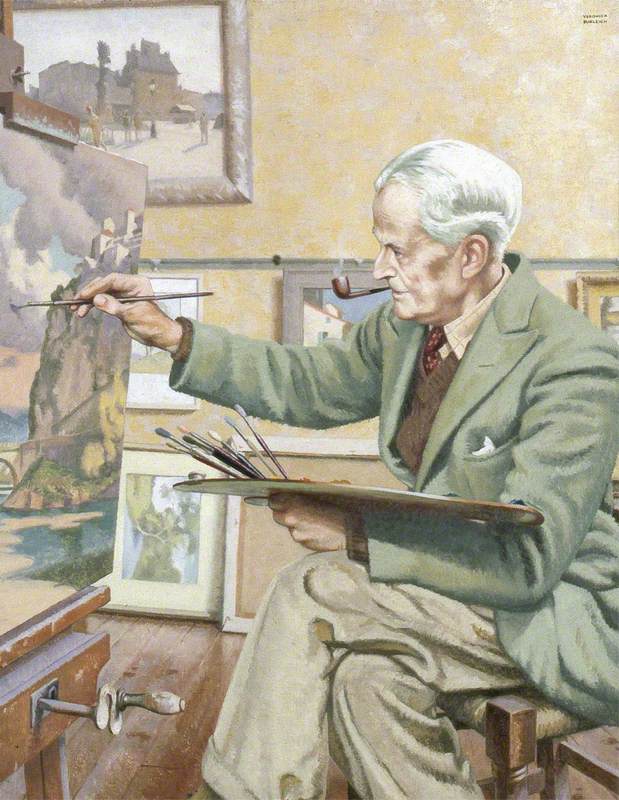

It is hard to imagine a more idyllic vision of a family painting holiday. Dad happy with pipe and brush, mum, a picture of contentment in sensible sun hat and daughter (self portrait) adding a touch of Hollywood glamour.

Self Portrait with the Artist's Parents

c.1937

Veronica Burleigh (1909–1998)

The year was 1937 and the young woman in the white dress is Veronica Burleigh looking down on mother Averil and father Charles. By this time all three were professional painters and longstanding exhibitors at the Royal Academy.

Although their reputations have faded we can piece together their story thanks, in part, to art historian Hilary Chapman who met Veronica a year before the painter's death in 1998.

'I went to visit her at her house in Henfield in Sussex when she was in her late eighties. She was surrounded by stacks of paintings by her parents and herself and, in a slightly muddled way, the family history began to emerge.'

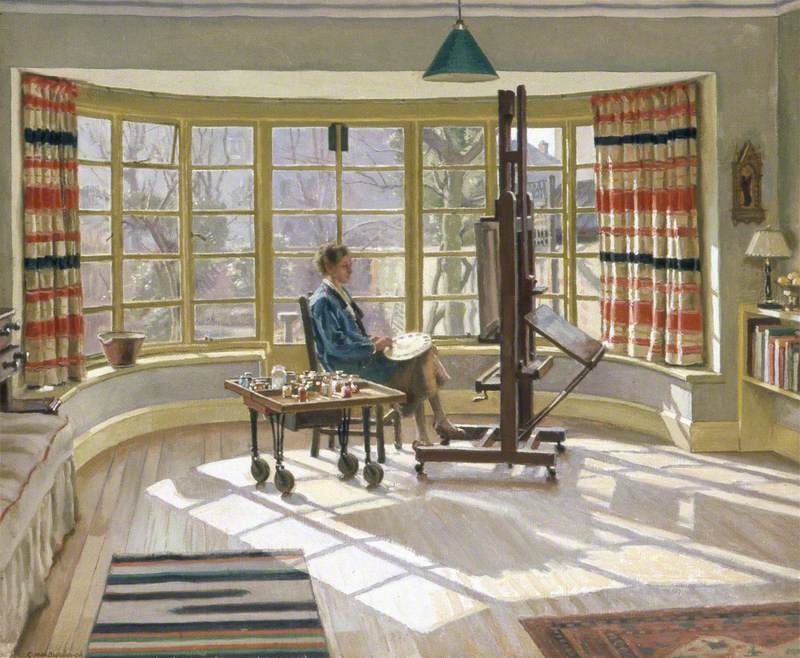

Veronica was born in 1909 in a house purpose built for art. Her parents had designed 7 Wilbury Crescent in Hove with the family business in mind. In 2011 the house came onto the market after the death of its then occupant, the flower painter Albert Williams. Somewhat neglected, it hadn't changed much since the Burleighs left half a century earlier.

7 Wilbury Crescent in 2011

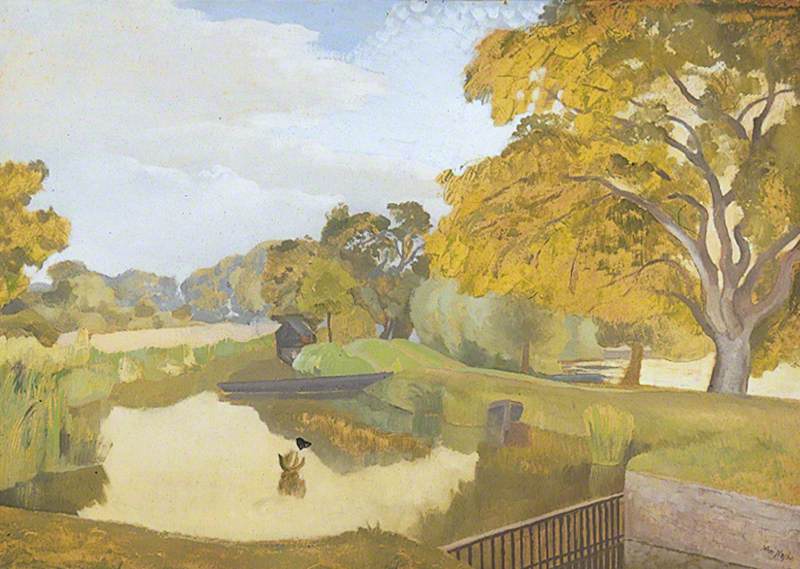

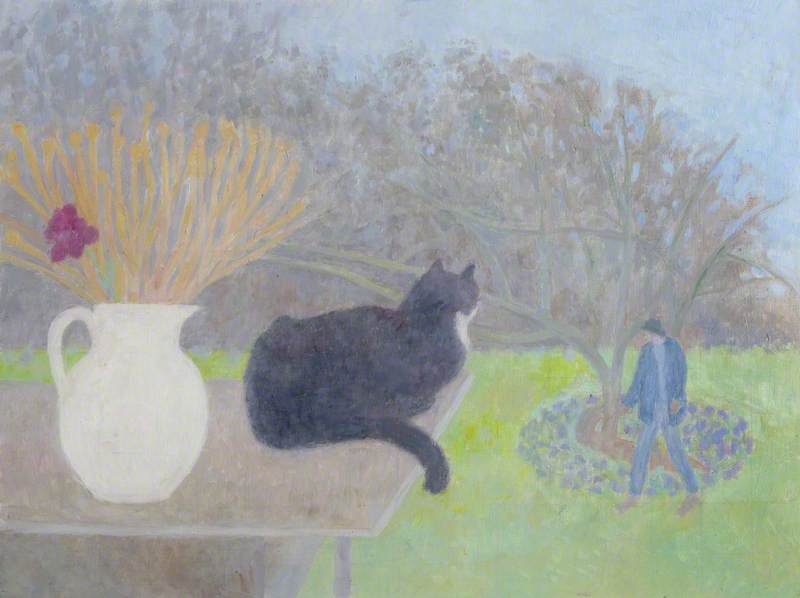

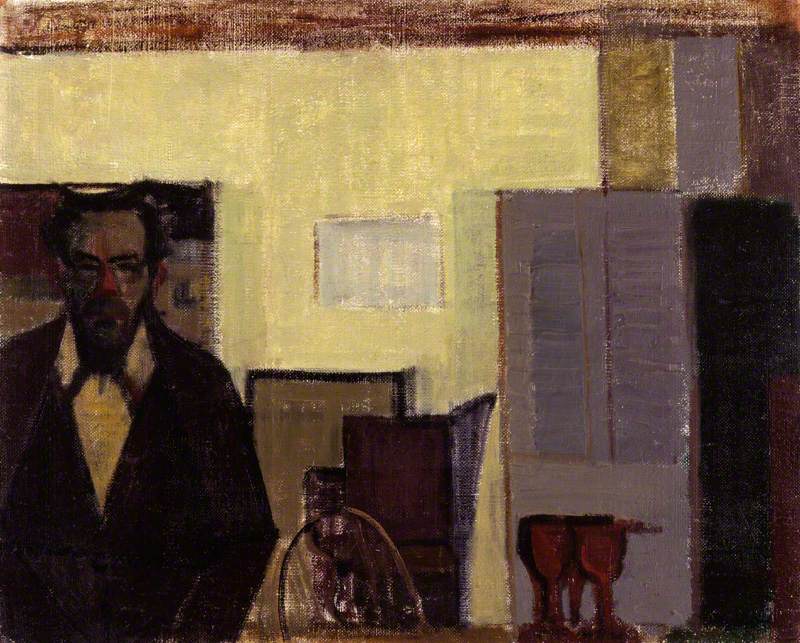

Although the top floor studio was the focus of much of their work, painting took place throughout the house, as this portrait by Charles of Averil in the drawing room shows.

Averil Burleigh (1883–1949), Painting at 7, Wilbury Crescent

c.1940

C. H. H. Burleigh (1869–1956)

She was perhaps the most talented of the trio. In 1913 her work featured in an article in the Studio Magazine. The anonymous author commenting: 'She was fortunate in marrying an artist whose help and encouragement have been of much service to her, so that instead of relinquishing her work, as so often happens in such cases, she has devoted herself to it more ardently than before.'

Averil illustrated plays by Shakespeare and poems by Keats in a courtly, romantic style and later became a leading figure in the revival of the use of egg tempera recalling artists of the Italian Renaissance.

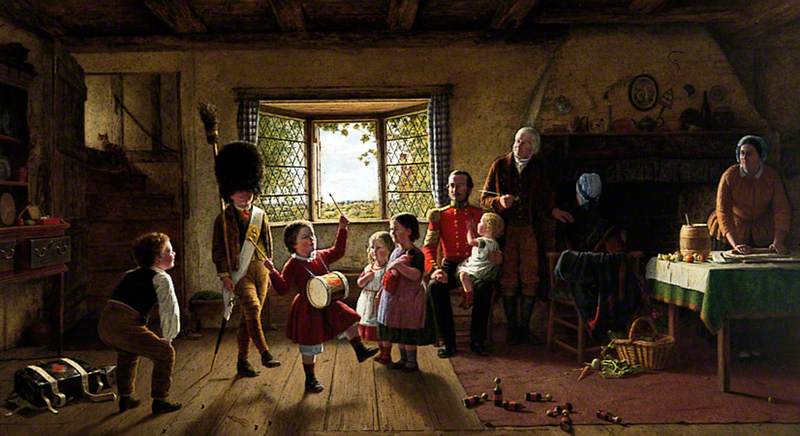

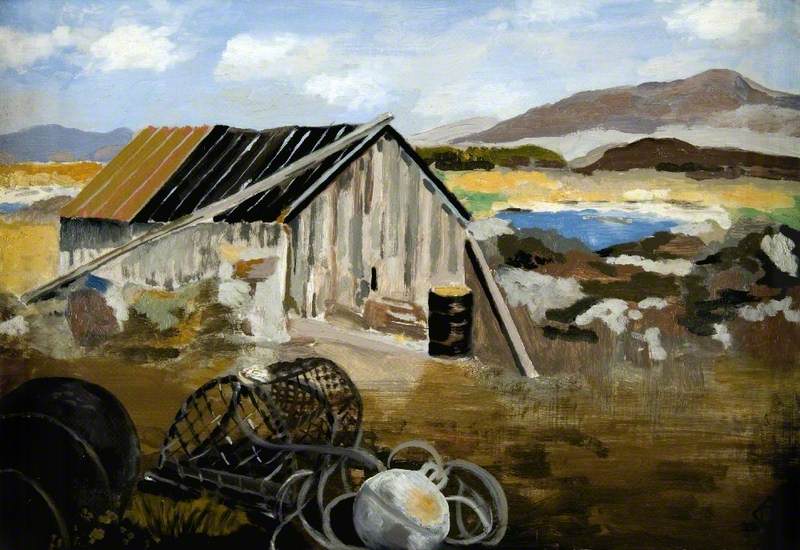

All the family were involved with art societies in Brighton and Charles, in particular, was a chronicler of life in the seaside resort. In the First World War he recorded the transformation of the Royal Pavilion into a hospital for Indian soldiers.

Music Room of the Royal Pavilion as a Hospital for Indian Soldiers

1915

C. H. H. Burleigh (1869–1956)

Later, in the 1920s, he captured the jollity and colour of Brighton in peace time.

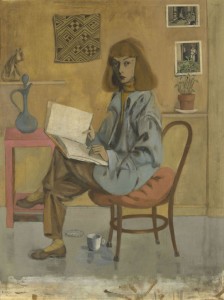

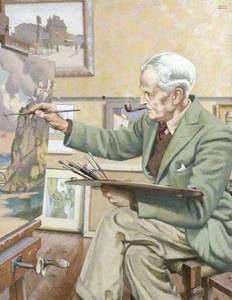

Veronica won a scholarship to the Slade and became an accomplished portrait painter. This portrait of her father dates from the Second World War when she served with the Women's Auxiliary Air Force.

Portrait of the Artist's Father

c.1940

Veronica Burleigh (1909–1998)

In middle age, Veronica spent several years in Africa where the Prime Minister of Rhodesia Ian Smith was among her sitters. The family never became rich from their brushwork, often relying on Averil's flair for buying and selling shares and Charles' occasional work as a prep school art master.

In an article for the Parents' Review, a magazine for parents and teachers, Charles said that children should be encouraged to observe painters at work. 'If you are spending the summer holiday in a place where painters congregate... let the children look over them. The painter probably won't mind (he is used to being looked upon as a sort of itinerant Punch and Judy show), and it may spur the children's interest.'

We will never know how many painters were inspired by watching the Burleighs at their easels during those English summers between the wars.

Charles died in 1956 aged 87 outliving Averil who had a fatal heart attack in 1949 aged 66. The glamorous Veronica, a devotee of fast cars and gardening, never married but, after an adventurous life, returned to Sussex where she died in 1998 at the age of 89.

James Trollope, author and columnist