Since the infamous tales of the nineteenth-century artists Richard Dadd and Vincent van Gogh, a history of art connecting creativity and mental health has come into existence, one that has also categorised such artists under the label of 'outsider art'.

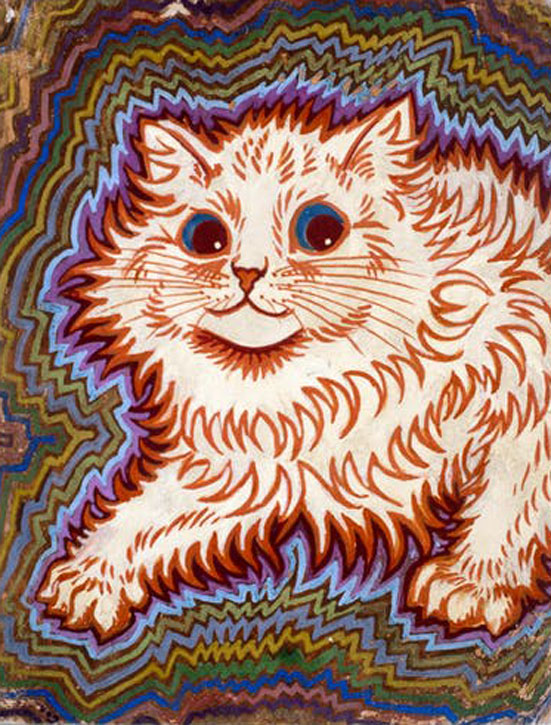

Louis Wain, an artist of psychedelic cats who popularised the feline creatures in Victorian and Edwardian Britain – at a time when they were not yet widely thought of as beloved pets – is one of the most famous examples.

Film still from 'The Electrical Life of Louis Wain'

A new biopic celebrating the eccentric painter, The Electrical Life of Louis Wain, directed by Will Sharpe and starring Benedict Cumberbatch, reveals more about the cat fanatic's unusual and tragic story. Although not to everyone's taste, Wain's colourful paintings and illustrations captured the imagination and attention of British society, and his work is still held in UK collections today.

Born in 1860, with a cleft lip and latent schizophrenia that would only be diagnosed later in life, Wain could not start school until the age of 10 because of his weak physical disposition. His father William worked for a textile firm and his mother Felicia, a French emigré, designed carpets. Raised in Clerkenwell in London, Wain was the elder brother to five sisters. When his father died when Wain was only 20, as the only male in the household he became the sole provider for his younger sisters and elderly, invalid mother.

But Wain's unusual temperament compounded by his interest in art did not make him an easy man to employ, as shown in Sharpe's film. From an early age he was known to wander about the city, drawings things he saw at electric speed. He went on to study at the West London School of Art where he taught briefly, before becoming a freelance artist. But with his unsteady income, the Wain family couldn't support themselves financially. None of his younger sisters were able to secure a marriage.

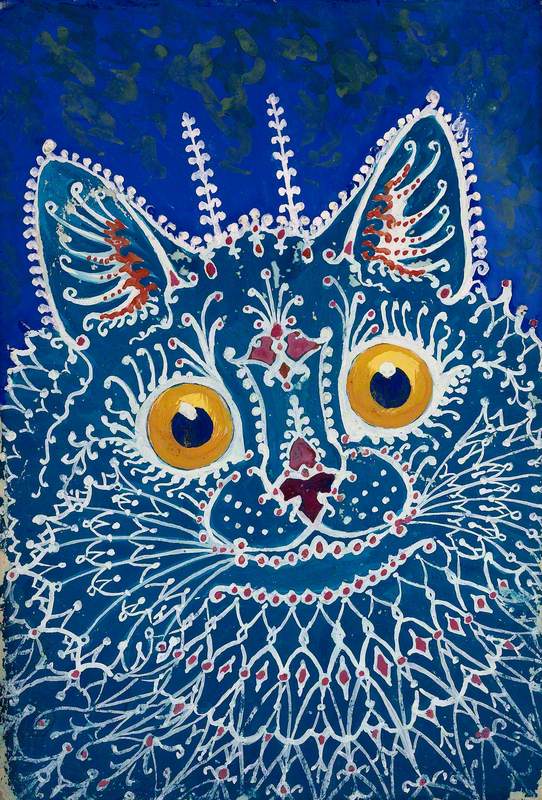

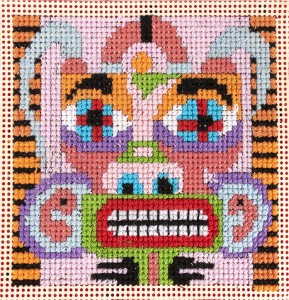

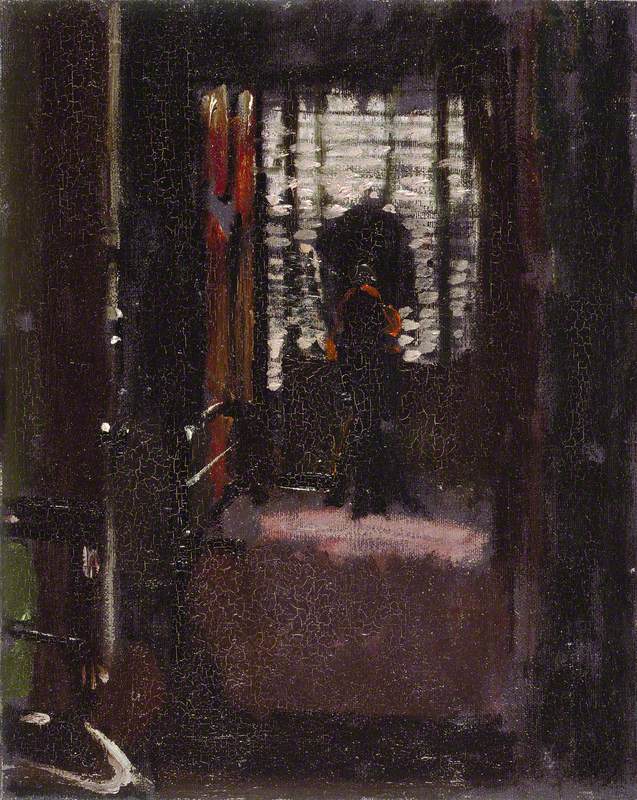

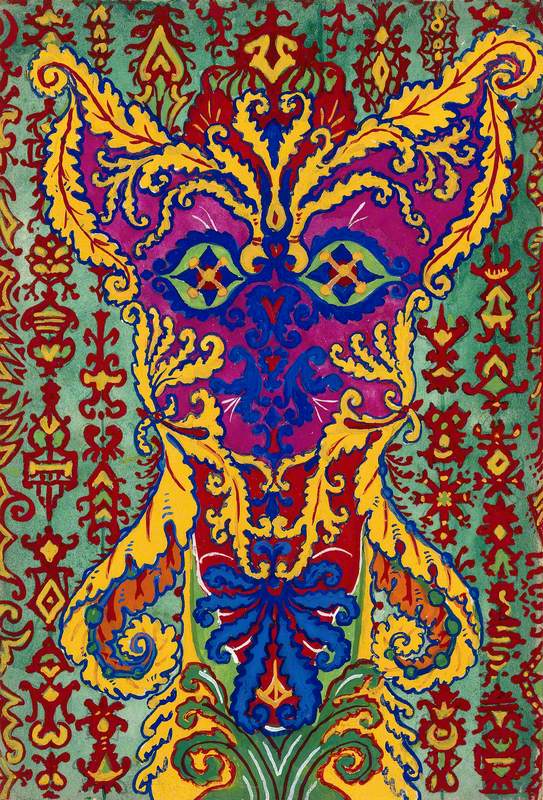

Kaleidoscope Cats III

by Louis Wain (1860–1939)

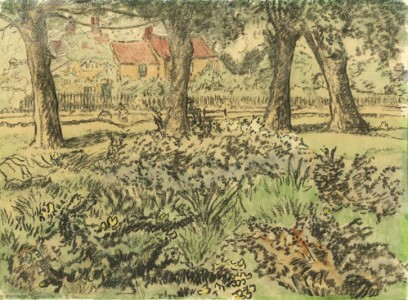

Wain did eventually find success as a freelance artist, receiving recognition for his detailed and idiosyncratic drawings of animals and pastoral scenes. He received positions at several newspapers, including the prestigious The Illustrated London News where he was employed as a staff illustrator, roughly between 1886 and 1890.

At the age of 24, he married Emily Richardson, the governess in the Wain household, employed to teach his younger sisters. Emily was at least ten years his senior and the relationship caused a wave of controversy that rippled beyond his family, and into the wider London community. Richardson unfortunately developed breast cancer not long after and died from the illness in 1887. To comfort his beloved wife, Wain adopted a black and white cat named Peter, a moment that sparked his lifelong adoration for the animals.

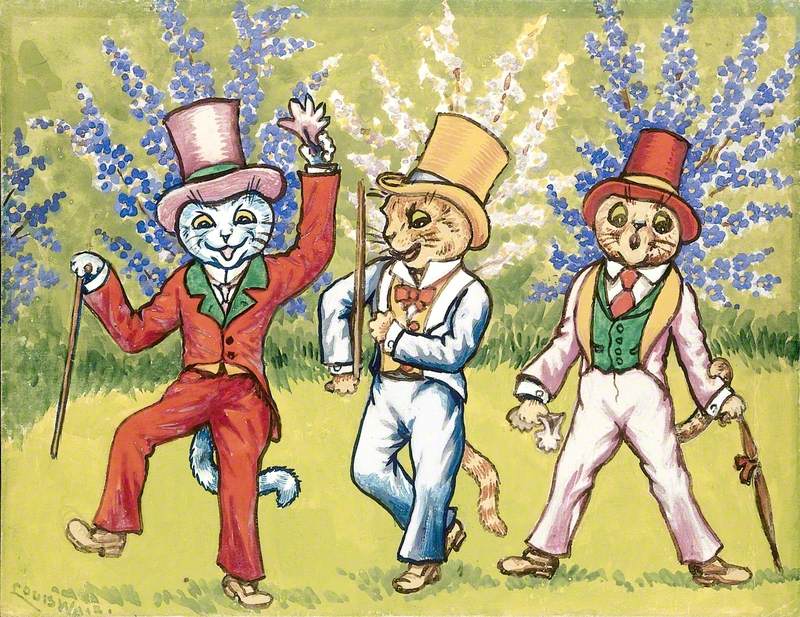

After Emily's death, Wain's intense grief was sublimated by his fixation with drawing cats, and the obsession brought his illness to the fore, gradually manifesting itself. Although cats were often likened to vermin and not generally treated as household pets – making the subject matter unusual for the time – it was met with success amongst Victorian and Edwardian audiences. From the 1880s until the outbreak of the First World War, the 'Louis Wain cat' became a popular cultural phenomenon in Britain and could be found in prints, books, magazines, postcards and greeting cards.

In 1886, the editor of The Illustrated London News commissioned Wain to create a poster for the magazine: A Kitten Christmas Party, a moment that represented the peak of his fame. Between 1898 and 1911, he was appointed chairman of the National Cat Club, and he was also involved with a number of other animal rights organisations, including the Anti-Vivisection Society.

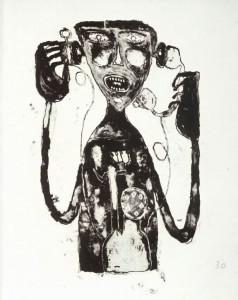

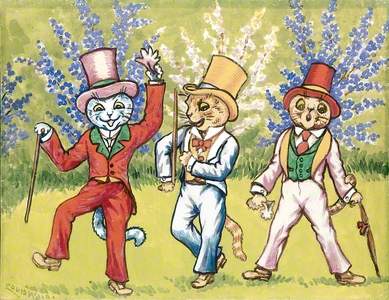

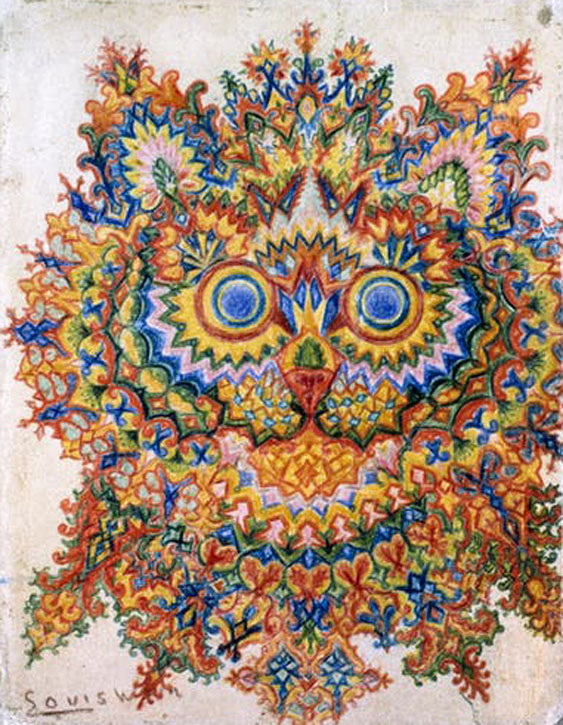

A Cat Standing on Its Hind Legs, Formed by Patterns Supposed to Be in the 'Early Greek' Style

Louis Wain (1860–1939)

The style of Wain's cats was not directly influenced by a particular artistic movement or genre, though some have argued his eccentric style precipitated the arrival of abstraction. Due to the detachment from any artistic school or movement, Wain has also been categorised as an outsider artist, a term coined by Roger Cardinal in 1972.

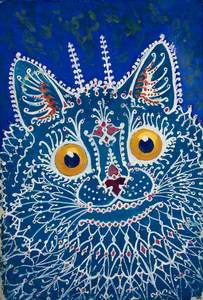

Kaleidoscope Cats IV

by Louis Wain (1860–1939)

Vibrantly colourful, kaleidoscopic and even anthropomorphic (his cats were often depicted drinking tea, playing cricket, or wearing suits to the opera), his surreal vision was regarded as charming and humorous by his audience. Some interpreted the 'Louis Wain cat' as a parody of late nineteenth-century genteel society, though as Sharpe's biopic suggests, he treated his feline subjects with an earnest admiration.

Sharpe's film also draws strong connections between Wain's lively imagination and his fascination with the technology of electricity, which had only been recently introduced to Britain. In 1881, the first public electricity generator had been installed in Godalming, Surrey, and the Electric Lighting Act of 1882 was the first parliamentary measure to distribute and regulate electricity across the country. Art historians have noted that Wain's energetic and dynamic style took on the imaginative, aesthetic qualities of electric currents. Frances Spalding wrote that his works 'became frenzied and jagged, sometimes disappearing into kaleidoscopic shapes.'

Despite his fame, Wain never earned much money during his lifetime. He made the fatal error of not copyrighting his images, meaning they became public property. As Manohla Dargis wrote for The New York Times, Wain's images were 'commodities of the humblest, most populist sort, not rarefied art-market fetishes.' He was also noted for being highly impractical in business affairs, much to the frustration and humiliation of his unmarried sisters.

Louis Wain

1900s, bromide postcard print by unknown photographer

In 1907, he travelled to New York, where he was employed to draw comic strips for newspapers, though he was not received as favourably in the US as he had been in Britain. During the war, Wain's poverty increased and symptoms of his illness accelerated after he was hit by tragedy after tragedy. When his psychosis made his behaviour increasingly erratic, leading to his initial committal to Springfield Mental Hospital in Tooting, public figures such as the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin and the prolific writer H. G. Wells (portrayed by Nick Cave in the biopic) made appeals. Wells allegedly said: 'He has made the cat his own. English cats that do not look and live like Louis Wain cats are ashamed of themselves.'

"Featuring every kind of cat you can imagine and more, an exceptional exhibition showcasing Louis Wain's dazzling, vibrant, eclectic illustrations." Time Out.

— Bethlem Museum of the Mind (@bethlemmuseum) October 17, 2021

'Animal Therapy: The Cats of Louis Wain' opens on 4 December!#LouisWainhttps://t.co/kUs7GZT9az pic.twitter.com/CJsRHTBK6E

Previously a gentle and quietly-spoken man, he had become uncharacteristically paranoid, abusive, and occasionally even violent towards his sisters with whom he still lived. He spent the rest of his life in numerous psychiatric institutions, including Bethlem Royal Hospital and Napsbury Hospital, where he remained until his death on 4th July 1939.

The first Labour Prime Minister, Ramsay MacDonald, also showed public support for Wain and his work, arranging for his sisters to receive a small Civil List pension in recognition of their brother's services to popular art. A memorial exhibition was held shortly after his death, and exhibitions of his work were held in London in 1931 and 1937.

Bethlem Royal Hospital, the world's oldest psychiatric hospital, has put on a major exhibition dedicated to the life and work of one its most famous inmates. 'Animal Therapy: the Cats of Louis Wain' will open at Bethlem Museum of the Mind from December 2021.

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

The Electrical Life of Louis Wain is available to watch on Amazon Prime

You can buy art prints of cats on the Art UK Shop, including several by Louis Wain

Further reading

Aida McGennis, 'Louis Wain: His life, his art and his mental illness', Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 1999