'If people really want to know me, let them look at my sculpture, because words are not my medium at all. It is sculpture that is my medium.' – Dora Gordine

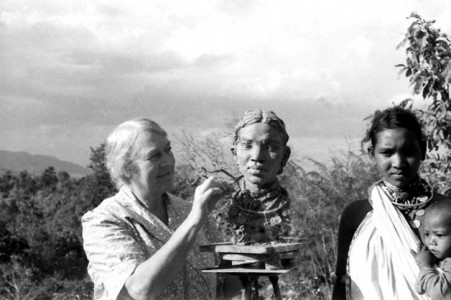

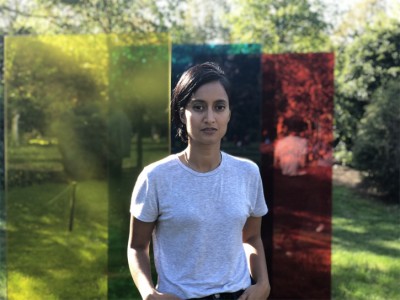

Still from the film 'Dora Gordine Ars Gratia Artis', 2018

In 1938, Dora Gordine (1895–1991) was at the height of her career and lauded for being 'possibly the finest woman sculptor in the world.' A fiercely passionate artist who was uncompromising in her artistic vision and personal life, Gordine would become the first woman to have her sculpture acquired by the Tate collection. In 1963, one of her sculptures was personally unveiled by Elizabeth II.

So why did Gordine – a pioneering female artist and charismatic force of energy – fall from the limelight?

Still from the film 'Dora Gordine Ars Gratia Artis', 2018

The former studio of the artist is now the Dorich House Museum and is arguably one of London's hidden gems. Situated on the corner of Richmond Park, the museum holds the largest collection of the artist's work as well as her vast number of collected antiquities and artworks from all over the world. The museum, alongside the documentary Dora Gordine: Ars Gratia Artis (2014) offers invaluable detail about Gordine's rise to artistic stardom during the first half of the twentieth century.

Born in 1895 in modern-day Latvia (formerly part of the Russian Empire), Gordine's Jewish family later moved to Tallinn, Estonia. From a young age, it was clear that Gordine would become an artist. Rather than playing with dolls as a child, she recalled her fascination with the rocks and stones she found on the seaside coast of Tallinn – 'I preferred those big barbaric lumps of stone.' As a young woman developing her burgeoning talent in Estonia and joining the Noor Eesti (Young Estonia) group of artists who were influenced by Art Nouveau, Gordine realised that her success would be limited if she remained in the same place. In 1924, she took the bold decision to move to Paris.

Gordine left Estonia for western Europe in the decade before the widespread persecution of Jews under the Nazis, and before the small Baltic territory was swallowed up by the Soviets during the Second World War. Historical records confirm that some of her remaining family in Tallinn perished. Her eldest brother Nikolai was executed by the Nazis and her sister Anna was sent to Siberia by the Russians, where she reportedly died. Gordine would never return to Eastern Europe, instead she settled in France, and later Britain, where she found professional success remarkably quickly.

Abandoning her past, Gordine appears to have assigned a new identity for herself once she left Eastern Europe. Aged 33 while living in France, she changed her surname 'Gorin' to 'Gorine', presumably as a way to Frenchify her surname and perhaps conceal her Jewish heritage. Those who later befriended her in England say she identified as a full-blooded 'Russian' and claimed her family were driven out by the Bolsheviks. A mysterious figure who avoided talking about her past, Gordine's conflicting documents have resulted in ongoing debates about her date of birth, place of birth and even nationality.

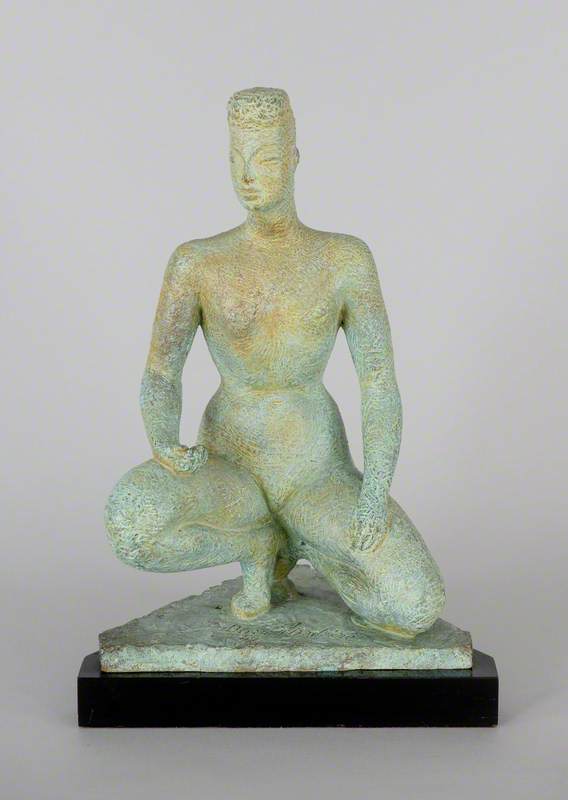

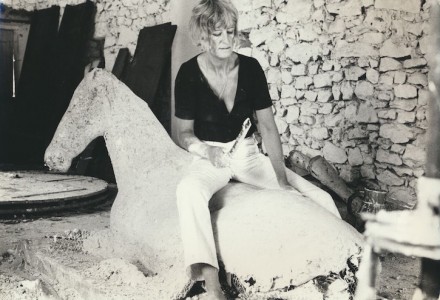

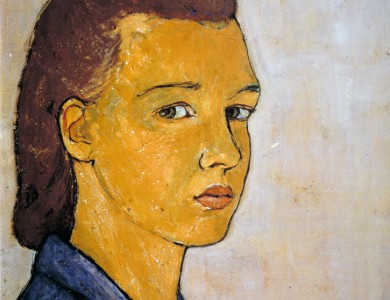

Self Portrait (Purple Head)

1930–1932

Dora Gordine (1895–1991) and Valsuani

Soon after arriving in Paris, Gordine earned a place at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, which was a huge accomplishment for a female artist of that time. One year later, she was invited to paint murals for the interior of the British pavilion for the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes.

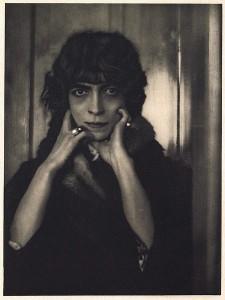

What arguably led Gordine to success as a young woman was her fearless approach to inserting herself into male artistic circles. For example, in this group photographic portrait taken in Tallinn, Gordine can be seen at the centre of the group. It is likely that she strategically placed herself into the middle of the group, so as to be noticed.

Still from the film 'Dora Gordine Ars Gratia Artis', 2018

Often described as a charismatic woman full of uninhibited artistic conviction, Gordine was not merely a member relegated to the fringes of artistic communities – a position many female artists were often pushed into. Rather, she was an emblematic and central figure in such circles. One leading architect in Paris, Auguste Perret became her close friend and active supporter of her career.

Chinese Head (Chia-Chu Chang/The Chinese Philosopher)

1925–1926

Dora Gordine (1895–1991) and Valsuani

In 1925, she embarked on creating this bronze statue of a Chinese philosopher, a sculptural portrait based on a real Chinese man she met while walking the streets of Paris. For this observational work, she was invited to exhibit at the Salon de Tuileries annual show in 1926, a highlight of her early career. In Paris, Gordine experimented with bronze, a challenging medium that ultimately became her signature. Curator Brenda Martin from the Dorich House Museum noted that she spent a great deal of time searching for chemicals that would create interesting colours in her statues.

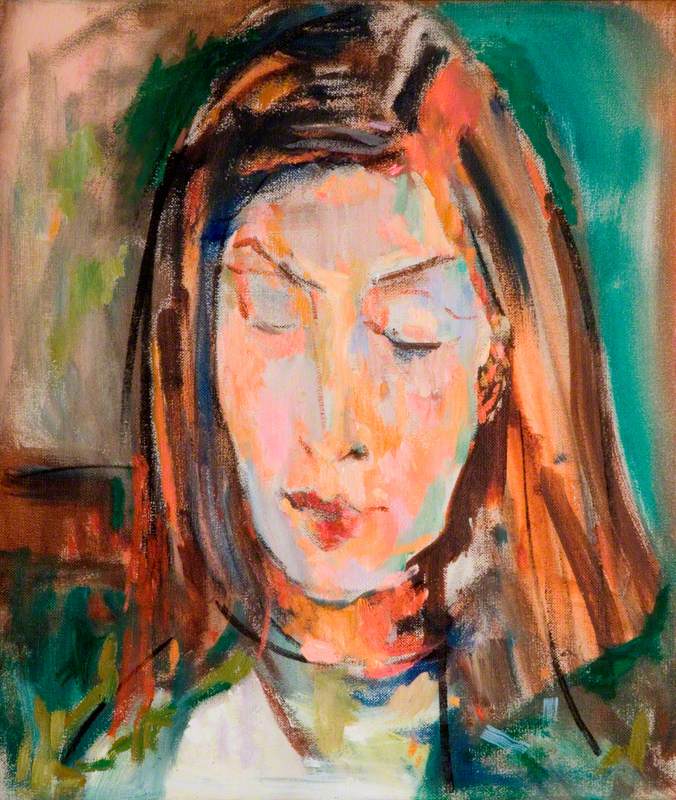

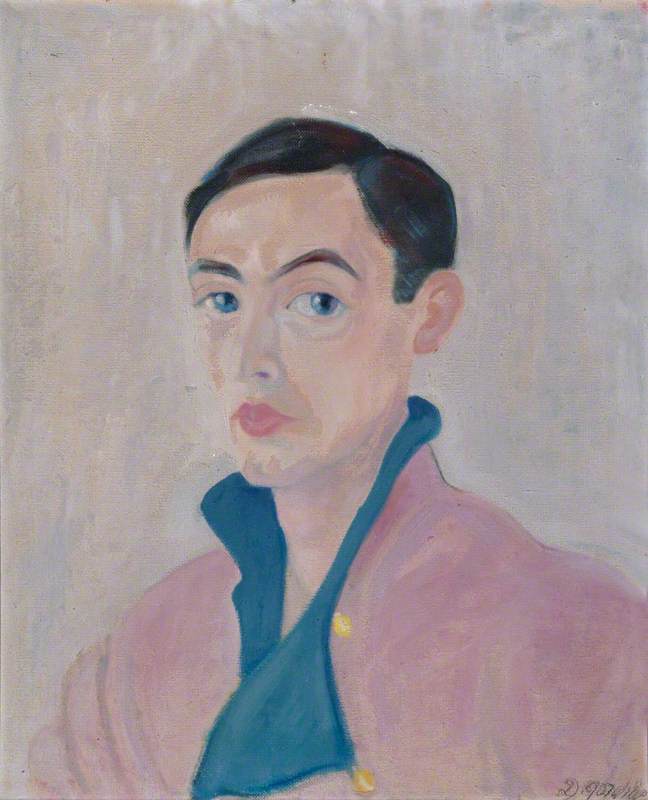

Richard Hare (1907–1966) as a Young Man

late 1920s

Dora Gordine (1895–1991)

While in Paris, Gordine first met the English aristocrat and Russian art expert Richard Hare (1907–1966), her patron and future husband. Significantly, Hare purchased her Javanese Head and donated it to the Tate collection. We also know that her bronze bust Mongolian Head was acquired by the collection in 1928 through an anonymous donor.

By the late 1920s, Gordine's work was being exhibited regularly and was shown alongside Barbara Hepworth when featured in the groundbreaking London exhibition 'Modern and African Sculpture' organised by Sydney Burney.

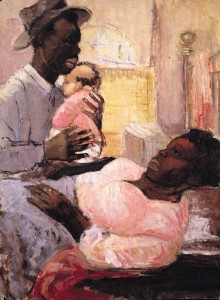

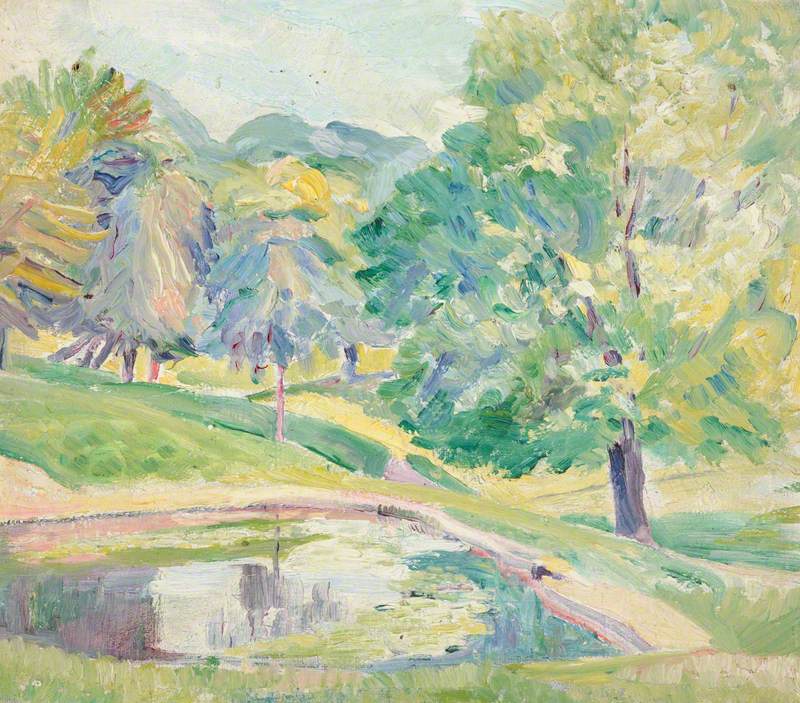

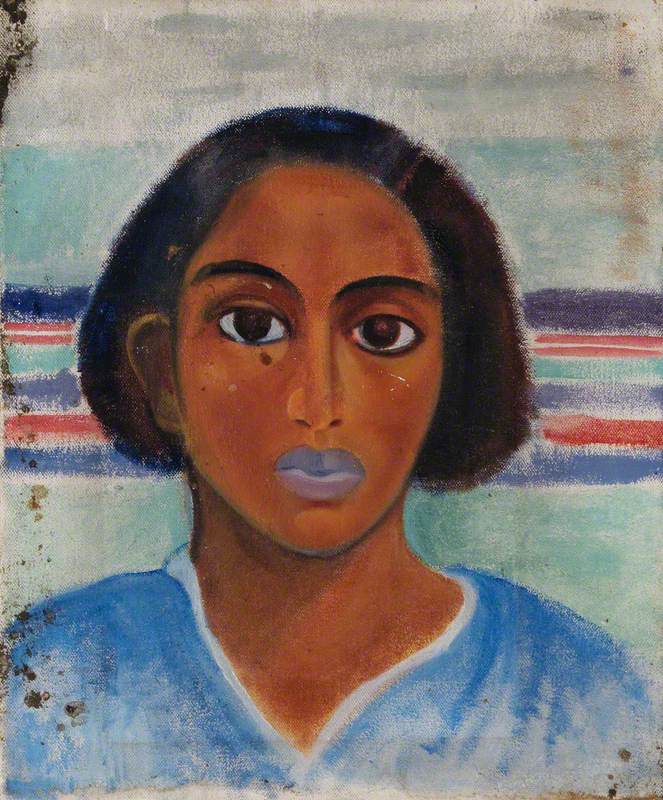

Oriental Girl against a Striped Background

Dora Gordine (1895–1991)

Rather abruptly, Gordine left Paris for Singapore in 1929, where she was told she could obtain lucrative commissions from the Municipality of Singapore. There, she married George Herbert Garlick (1886–1958) an art collector and doctor who was the personal physician to the Sultan. Marriage gave Gordine a British passport so, for five years, she travelled extensively around South East Asia, visiting British North Borneo, French Indo-China, Thailand, eastern Burma, Hong Kong, Canton and Shanghai, Bali, Java and Lombok. Influenced by her travels, she began to focus even more on 'exotic', or non-western subjects and she also started collecting.

In 1950, in a BBC interview, she reminisced: 'what a joy it was to bring back to Europe all these living memories of the Far East, after working there for five years; to arrange all these beautiful things in my home side by side with other treasures which I collected in Spain, Italy, France and England.'

Portrait of a Burmese Woman

1930–1935

Dora Gordine (1895–1991)

Gordine's marriage to Garlick was far from successful. They divorced on the grounds that the marriage was 'never consummated' and four days after the divorce was confirmed she married Hare, who was eleven years her junior.

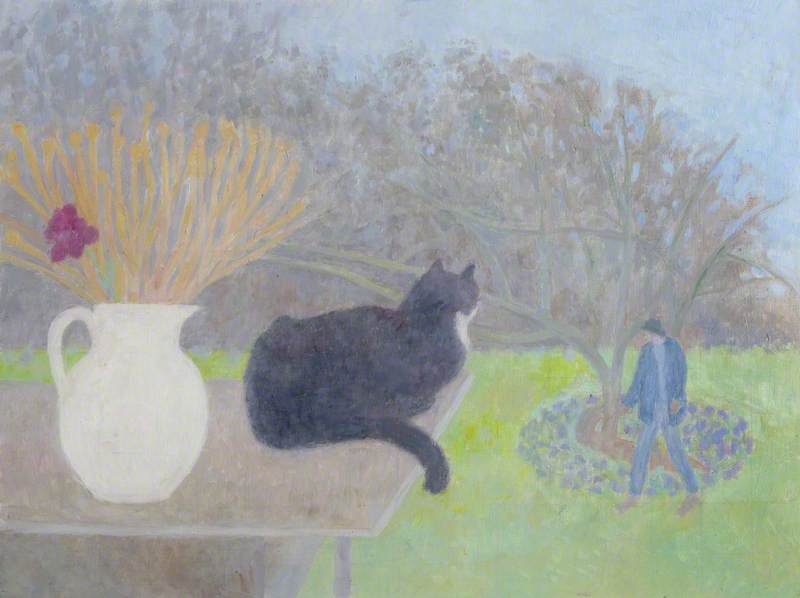

The Gallery, Dorich House

In 1936, Gordine started building the Art Deco modernist building, Dorich House. Serving as a home and studio, the house was named 'Dorich' because it referred to both names of Dora and Richard and it was considered something of a 'novelty' for being designed solely by a woman. Serving as an exhibition space and marketing tool, Dorich House allowed Gordine to socialise with sophisticated patrons and museum directors in her home, while simultaneously displaying her new works.

The Gallery, Dorich House

From the 1920s to the 1940s, Gordine befriended many of the European collectors and established a profitable market for her work. In London, she was introduced to members of the Bloomsbury Group and even sold her work to the notable industrialist and collector Samuel Courtauld. Through many of Hare's contacts, she was able to mix with the most affluent circles of London's high society, meeting influential celebrities like the actress Edith Evans, whom she sculpted in 1937.

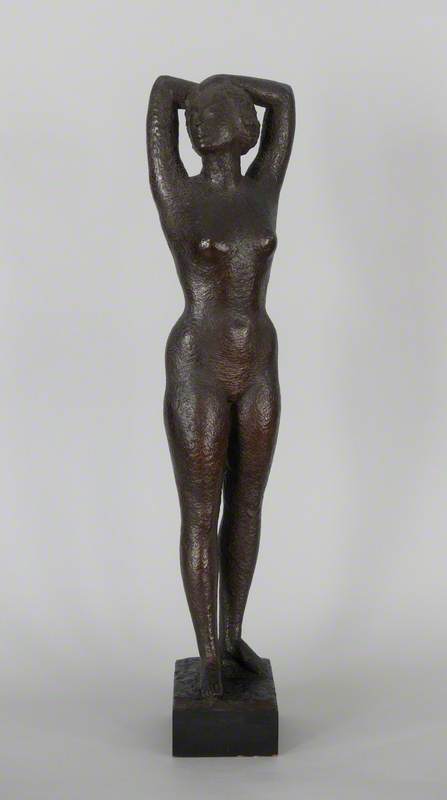

Standing Female Nude (Dame Edith Evans, 1888–1976)

1937–1938

Dora Gordine (1895–1991) and Valsuani

Known for her ability to capture the essence and personality of the individuals she portrayed, Gordine's work was praised for its realistic rendering of the human body and the weight of flesh.

From 1937 onwards, Gordine became a regular exhibitor at the Royal Academy. Yet, despite several nominations to elect Gordine as an associate of the Academy, she never became an academician – a sign of the establishment's clear reluctance to champion the careers of female artists.

After the Second World War, she created Typhoon, a bronze sculpture of an RAF pilot, Hedleigh 'Bobby' St George Bond, who had flown a Spitfire during the Battle of Britain. She continued to sell her work to prosperous patrons and collectors, exhibiting regularly at the Leicester Galleries. She even spent six months in Hollywood in 1948, where she was fêted by the Los Angeles film world.

An important highlight of Gordine's career came in 1963, when her sculpture Mother and Child was unveiled at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust in Sutton, Surrey, by Elizabeth II. This was her most high-profile public commission, with the bronze statue measuring three feet high and nine feet long.

Gordine's career continued to thrive until 1966, the year her husband Hare died of a sudden heart attack. In shock and grief, Gordine retreated from public life and stopped producing work. She ceased exhibiting and socialising, remaining alone in Dorich House until December 1991 when she died of a stroke.

So why is Gordine not more famous today? There appears to be a number of reasons why Gordine's life and work fell into obscurity.

Firstly, after the death of her husband, Gordine appeared to give up on her artistic ambitions.

On top of that, according to Jonathan Black, a Senior Research Fellow at Dorich House Museum, aesthetic tastes had radically shifted by the early 1960s, meaning audiences viewed her work and art collection as passé. Despite gathering many important contacts to museum directors and art patrons over the course of her life, Black suggests that Gordine's lack of involvement with post-war institutions such as The Arts Council (founded in 1945), or The Institute of Contemporary Art (founded in 1948), prevented her work from being promoted in the UK or abroad.

However more broadly, the fact that she was a female sculptor working in a male-dominated field clearly set her career back. Today it is widely acknowledged that female artists have struggled to receive the same institutional representation and accolade as their male counterparts. And sculpture, even more so than painting, has been historically regarded as a particularly 'male' artistic domain, most likely due to its challenging physicality and monumental scale. Perhaps conscious of this bias, Gordine refused to be called a 'sculptress'.

Although Gordine's work was neglected in the later years of her life and in the decades following her death, there have been significant retrospectives at The London Jewish Museum of Art in 2006, and at Dorich House Museum, Kingston University curated by Brenda Martin in 2009.

Mongolian Head (Head of a Tartar Woman)

1926–1928

Dora Gordine (1895–1991) and Valsuani

Let's hope Gordine's impressive career continues to be remembered, as undeniably she was shattering glass ceilings for female sculptors over a century ago. You can visit the home and studio of Gordine and Hare at the Dorich House Museum in Kingston.

Lydia Figes, Content Creator at Art UK