A Venn diagram comparing a motorway flyover, ancient Persia and the Jewish festival of Purim would find its unusual intersection at The Stained Glass Museum in Cambridgeshire.

Opened to the public in 1979, this independent museum based in Ely Cathedral displays over 130 illuminated stained glass windows from secular and sacred buildings from across the UK, Europe and further afield. Many of the windows have come into the museum's collection when their original buildings have been demolished and a new home is needed for these fragile works of art.

Stained glass is often associated with Christian places of worship, but is found in a variety of faith spaces, including mosques and synagogues. In all these sacred spaces, stained glass brings colour and light into the building, but the subject and imagery in stained glass differ in each context according to that faith, its laws and beliefs. Within a Christian context, stained glass is often figurative, but in Jewish law, idolatry is prohibited and thus people are not represented or depicted in synagogues. Instead, Jewish stained glass tends to focus on symbolic imagery and scripture.

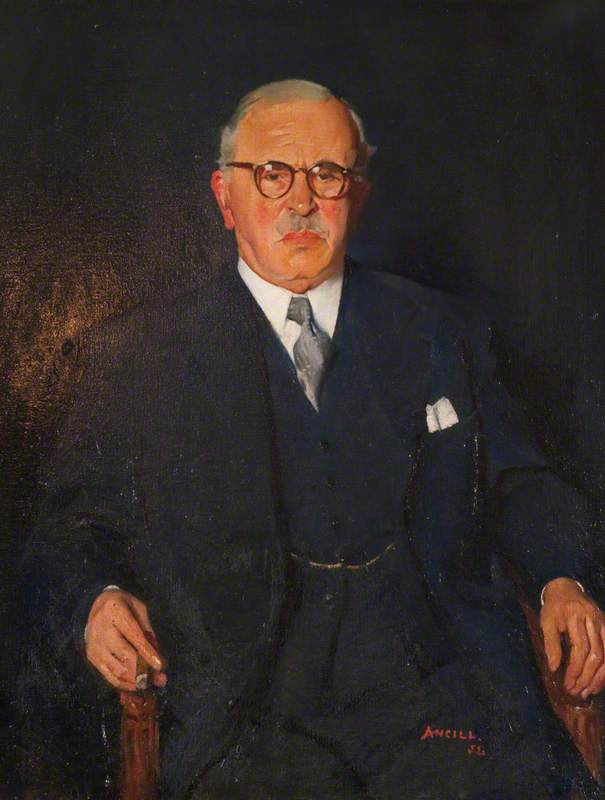

One such Synagogue window by the artist David Hillman (1894–1974), celebrating the Jewish festival of Purim, is on permanent display at The Stained Glass Museum. Born in Riga, Latvia, Hillman is the second child of an eminent rabbi and came to Glasgow from Belarus (then Russia) in 1908 with his parents and older sister. His father, Rabbi Samuel Isaac Hillman, was a renowned Orthodox Jewish Talmudic scholar, posek (a person who interprets Jewish law for the community) and rabbi. Hillman was appointed as a rabbi in Glasgow in 1908 where he served until 1914 when he was appointed a dayan (a judge) of the London Beth Din (Rabbinical Court).

David Hillman developed a keen interest in the arts in Glasgow and at age 15 he was awarded a scholarship to the Glasgow School of Art, where he studied for six years. He later studied at the Royal Academy in London, graduating in 1920, and was regarded as a prodigy by the British Jewish Pre-Raphaelite painter Solomon J. Solomon (1860–1927). During this period, Hillman also studied for the rabbinate and was appointed officiating rabbi at the Sandys Row Synagogue in East London, the oldest surviving Ashkenazi synagogue in London.

In the early 1930s, Hillman branched out to stained glass. He was commissioned to design a commemorative window for George V's jubilee in 1935 for Leeds Synagogue, as well as full sets of windows for synagogues in London. In the 1950s, he also designed windows for the Helchal Shlomo Jewish Heritage Centre in Jerusalem. Above all, Hillman was a Jewish artist living his Judaism through his art. He combined a formidable knowledge of the Hebrew scriptures with great artistic talent and dedicated much of his life and energy to an art form that compelled him. His artwork comes from a place of deep understanding of the complexities of the script and the portrayal of the festival stories.

The former Bayswater Synagogue that stood in Chichester Place, London from 1863 to 1965

One such commission, in the 1950s, was for a series of windows at the London Bayswater Synagogue, an Ashkenazi-Orthodox synagogue located in Paddington which was the oldest Ashkenazi place of worship in London. From the 1820s, many Jewish families had joined the westward expansion of London, and the need for a local synagogue was growing. Opened in 1863, it was one of the original five synagogues that formed the United Synagogue in 1870.

By comparison with others in London, the Bayswater Synagogue was mostly spared in the war, apart from its board room which was destroyed alongside its portrait gallery of nineteenth-century community leaders. On the same night that this damage occurred, 10th May 1941, Luftwaffe bombs destroyed both the Great and Central Synagogues of London.

Having survived the London bombing relatively intact, it was ultimately the building of a motorway flyover in the 1960s which saw the end of the London Bayswater Synagogue. At this point, the entire scheme of non-figurative stained glass windows by David Hillman was removed and placed in store. Each depicted a different festival, focusing on associated symbols and objects, and was placed in memory of synagogue members. Several of the windows were relocated to Borehamwood Synagogue in the 1980s, where they found a new home. One window, depicting the festival of Purim, was donated to The Stained Glass Museum in 2007, where it has been on display ever since.

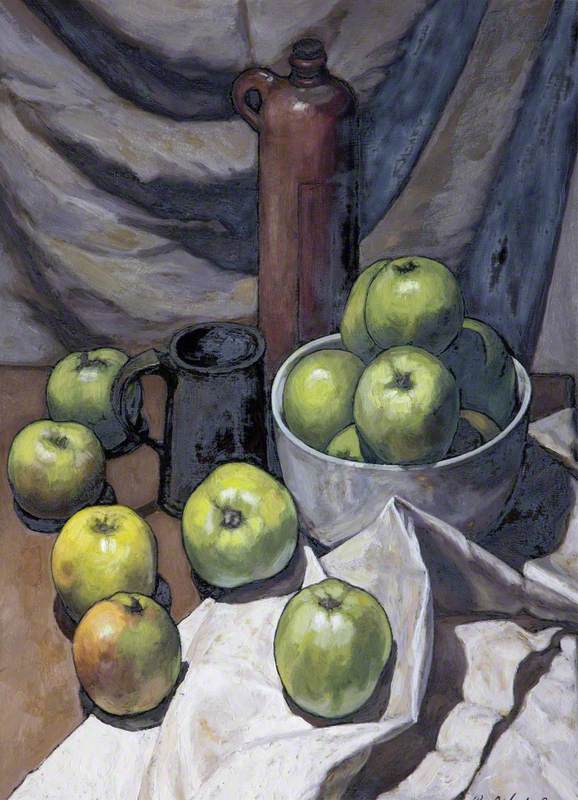

The Purim window is bursting with colour and rich decoration, including baskets of overflowing fruit, delicious cakes topped with walnuts, glazed fruits, figs and wine. Each item has a gift tag attached, waiting to be distributed to friends, neighbours and the less fortunate. Alongside the traditional foods, the artist's inclusion of bananas places the panel in the modern age.

In the scroll of Esther, it says: 'As the days wherein the Jews rested from their enemies, and the month which was turned unto them from sorrow to joy, and from mourning into a good day: that they should make them days of feasting and joy, and of sending portions one to another, and gifts to the poor' (Esther 9:22, KJV).

During Purim, Jewish people listen to the Megillah (the scroll of Esther) being read in synagogue twice through. This ritual reading is celebrated in William Rothenstein's painting Reading the Book of Esther, which depicts three rabbis with long beards, wearing kippot and tallits draped over their heads, reading at a lectern. Jewish people also enjoy a festive meal, a Purim Seudah, as well as completing charitable acts, matanot l'evyonim, and giving food and gifts, mishloach manot. Passages from the scroll of Esther, in Hebrew, are depicted throughout the border of the Hillman panel, reminding viewers of the importance of this festival.

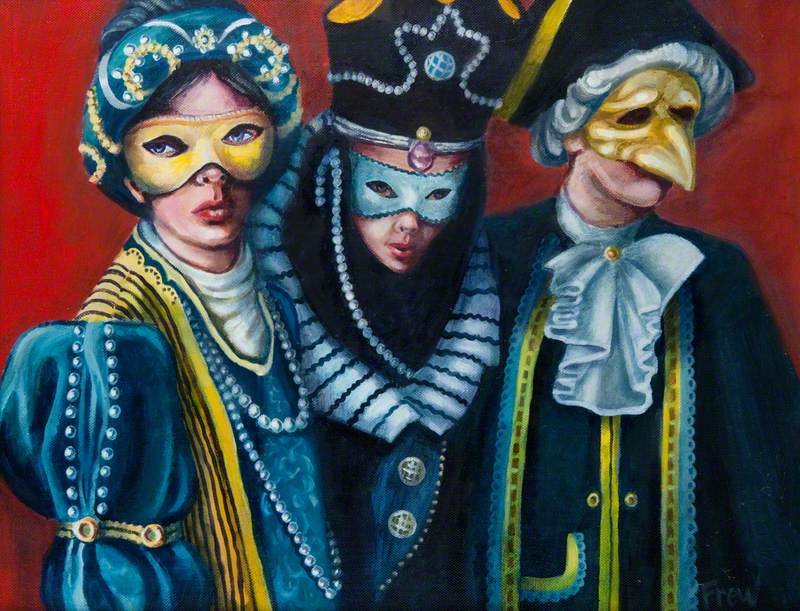

Purim is one of the most joyous Jewish festivals each year, filled with celebratory food, drink, treats and often fancy dress. The fun is not just for children though – rabbis have been known to dress up as popular cartoon characters to lead services! Purim is celebrated each year on the 14th of the Hebrew month of Adar, often with parties, merriment and lots of fun.

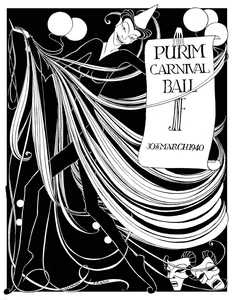

Hannah Frank's black and white lithographic print invitation to a Purim carnival ball in 1940 captures the party atmosphere of these events. The illustration shows a characteristically elongated figure of a jester wearing a conical party hat, carrying balloons and streamers. He holds up the invitation for a Jewish National Fund event. Frank was a fellow Glasgow artist and contemporary of Hillman's. She provided illustrations for various Jewish organisations in the 1940s.

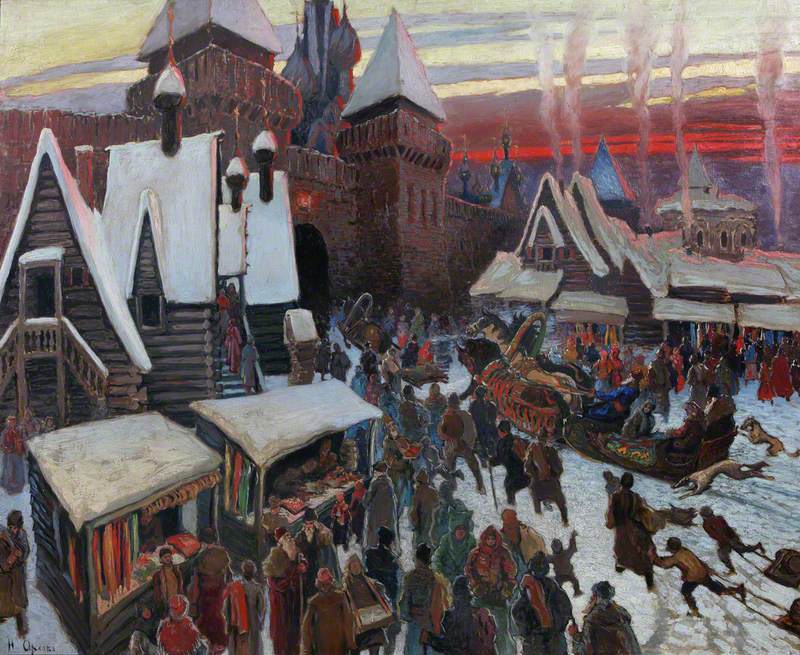

The Purim festival commemorates the survival of the Jewish people who, in the fifth century BC, were marked for death by their Persian rulers. Haman, a royal vizier to Ahasuerus, King of Persia, conceived an evil plot 'to destroy, kill and annihilate all the Jews, young and old, infants and women, in a single day' (Esther 3:13, KJV).

Persian Empire ruler King Ahasuerus had his wife, Queen Vashti, executed for failing to follow his orders. A beauty pageant was arranged to find him a new queen. A Jewish girl, Esther, found favour in his eyes, though she refused to divulge her nationality.

Meanwhile, the evil Haman had now been appointed as prime minister. Mordechai, the leader of the Jews and cousin of Esther, defied the King's orders and refused to bow to Haman. Haman was incensed and resolved to take revenge against all the Jews. He convinced the King to issue a decree, enacting his evil plan and threw lots to determine the 'lucky' day. The 13th of Adar was selected, as recorded in the Megillah, the scroll of Esther. The word Purim comes from the ancient Persian word 'Pur' meaning 'lot'.

Mordechai, now aware of this plan, pleaded with his cousin Esther to ask the King to save the Jewish people. He galvanised all the Jews, convincing them to repent, fast and pray to God, whilst Esther asked the King and Haman to join her for a feast where she bravely revealed her Jewish identity, putting her own life at risk on behalf of her people.

Esther revealing her identity is a key moment in the Purim story. The scene is carved into a sixteenth-century oak chest, now in the collection of the Jewish Museum: Esther appears with King Ahasuerus and Mordechai at the feast. In Sebastiano Ricci's painting Esther before Ahasuerus, Esther presents herself to the King of Persia – risking her life, as approaching the king without permission was punishable by death.

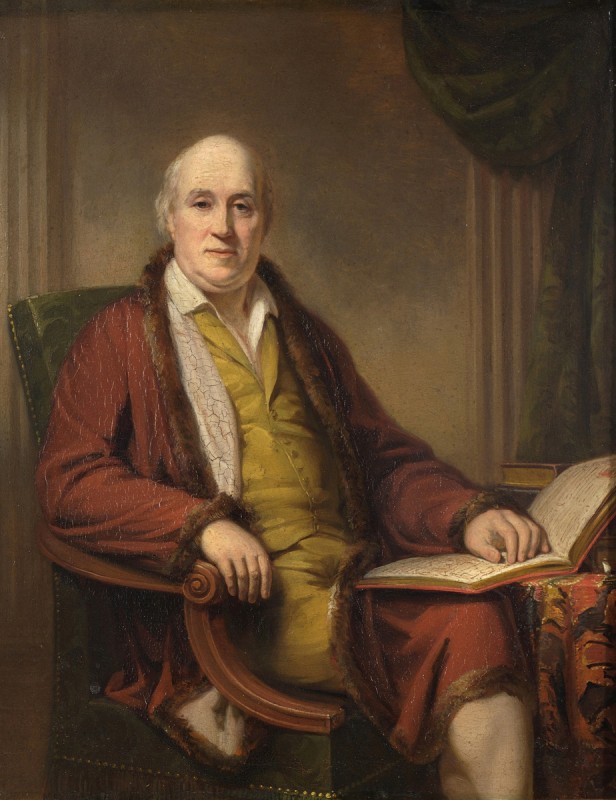

When Ahasuerus learns of Esther's true identity he reversed Haman's decree, and instead of ordering the Jews to be killed, he ordered Haman and his sons to die instead. British painter Edward Armitage focused on this moment in his 1865 painting The Festival of Esther. King Ahasuerus, at the centre of the scene, with his left hand on the hilt of his sword, is shown in anger. Haman begs Esther for mercy as guards begin to drag him away. Mordechai stands over the scene from the opposite end of the table. Esther's status and innocence are emphasised by her white costume.

Mordechai was appointed prime minister in Haman's place, and a new decree was issued, granting the Jews the right to defend themselves. It was on the 13th of Adar that the Jews mobilised and killed many of their enemies. On the 14th of Adar, they rested and celebrated. This defeat against the enemy and celebration is remembered each year at Purim.

In 2023, Jewish people all around the world will celebrate the festival of Purim from the evening of 6th March until the evening of 7th March.

We wish a Chag Purim Sameach to all!

Emily Allen, Collections Engagement Officer and Jasmine Allen, Director and Curator at The Stained Glass Museum, with thanks to Frances Jeens

To read more about Purim, visit the Jewish Museum's website and Chabad.org

.jpg)