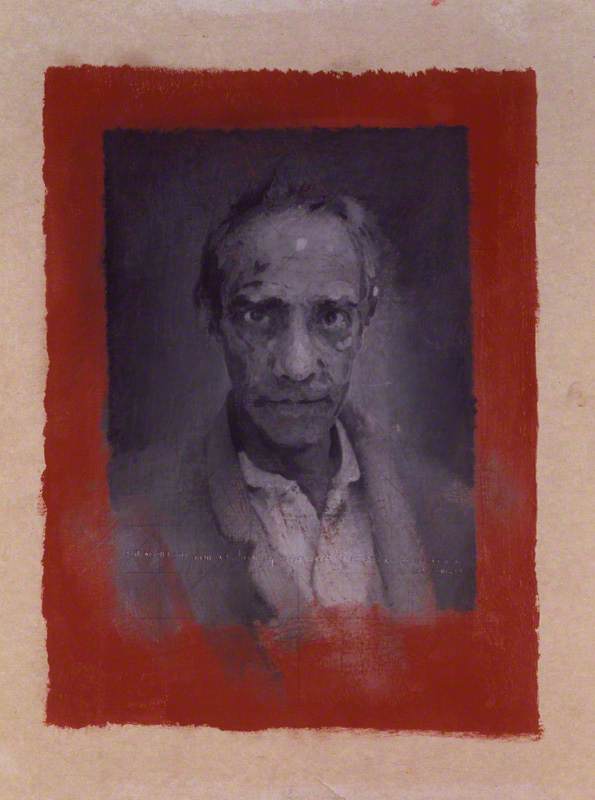

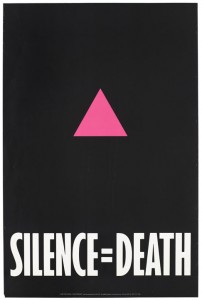

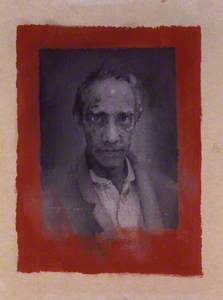

Derek Jarman (1942–1994) was an artist, writer and filmmaker who found his idiosyncratic voice as a gay rights activist against the backdrop of the AIDS crisis throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

Candid about his status as HIV positive, much of his film oeuvre showcases proto-queer protests against the British media's treatment of AIDS victims as social pariahs, as well as a general defiance against the Thatcherite government, who passed the Section 28 Local Government Act in 1986, which warned that a local authority could not 'intentionally promote homosexuality or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality.'

In 1994 Derek passed away. However, his legacy lives on in queer cinema, as a filmmaker who unabashedly championed the visibility of a homosexual narrative. He trod the line between camp pastiche and vengeful civil disobedience, and even today there is much to be learned from the defiant rage of Jarman.

Prospect Cottage

This LGBTQ+ History Month marks a critical moment in Jarman's legacy. In the late 1980s, Jarman found sanctuary in Prospect Cottage, a small house on the windswept peninsula of Dungeness.

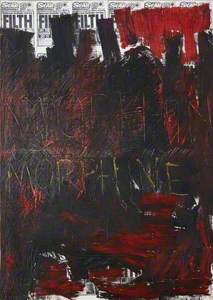

During his time there his creative outpouring was immense – from flotsam and jetsam sculptures to paintings of red scratchings and black tar. It was also the location of his 1990 film The Garden, a psychedelic retelling of the life of Jesus as a gay man during the AIDS crisis, a highly personal film for Jarman which raises questions about his own mortality.

Prospect Cottage

The cottage has become something of a shrine to the artist since his death. However, after his partner Keith Collins also passed away in 2018, it has been facing a turbulent future and at risk of being bought by a private company.

Art Fund writes 'Prospect Cottage and its iconic garden stand testament to his defiant spirit, and have the potential to inspire artists and visitors long into the future.'

Until 31st March 2020, Art Fund is running a star-studded campaign to save the building as an archive of his work and a site of pilgrimage for many around the world. The idea of conservation may seem at odds with an artist whose work dealt so closely with the anachronistic and who made active interventions into conventions of time and stability.

Art Fund's #saveprospectcottage campaign

(Left to right): Creative Folkestone director Alastair Upton, actors Julian Sands and Tilda Swinton, artist Michael Craig-Martin, Art Fund director Stephen Deuchar, artist Tacita Dean and Tate Director Maria Balshaw

Throughout his film career, Jarman displayed a profound historical imagination, rethinking the Roman tale of Saint Sebastian and the life of the artist Caravaggio as biopics of homoerotic desires.

His work speaks to the practice of queer nostalgia – the reinsertion and privileging of queerness into a narrative previously denied to LGBT+ people. Against the backdrop of Thatcherite Britain, Jarman reimagines the marginalised as heroes of their own stories. His films are brash, sexual and technically overwhelming, often becoming an immense filmic collage of disparate images.

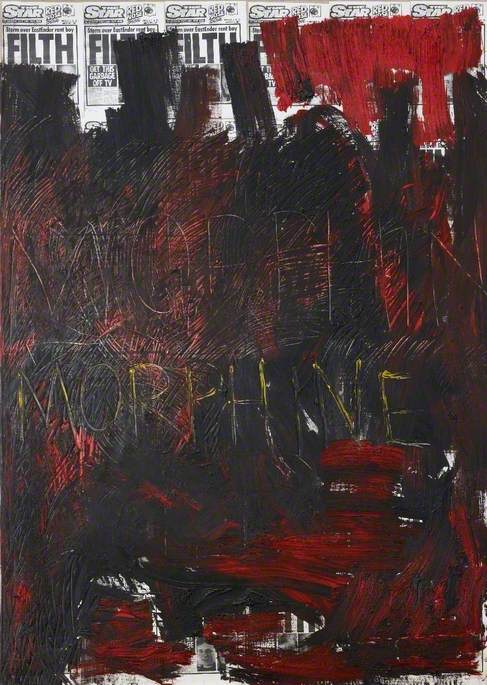

This is especially apparent in his 1987 film, The Last of England. Widely referred to as Jarman's 'angriest film', his collage of Super 8mm footage presents an England which is post-apocalyptic, a macabre vision of a country which Jarman saw as ravaged by Thatcherism.

The film becomes a barrage of images and sequences, almost biblical in its fire and brimstone representation of England. Convention is discarded in favour of chaos – London becomes a site of rubble, fire and smoke, a literalisation of the ruin of Britain under a right-wing rule. All images of the establishment are corrupted. The union jack becomes a site of sexual intercourse, substance abuse and violence, interlaced with imperial stock footage.

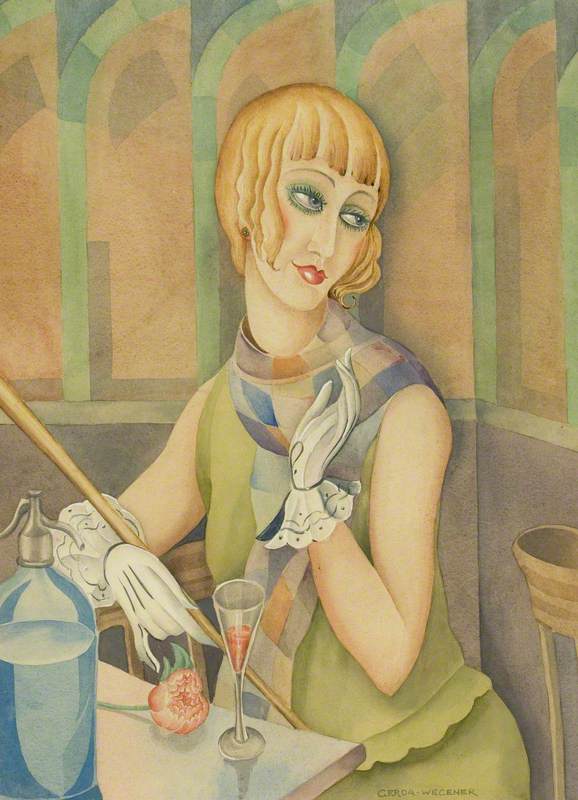

The Last of England seems a far cry from Jarman's inspiration – Ford Madox Brown's painting of the same name. However, despite the palpable anger of the film, there is a sense of hope, which we can see as deriving from Brown's painting. Brown's 1855 oil painting depicts a couple leaving England to begin a new life in Australia with their baby. Much like Jarman, there is an autobiographical element to the artwork, as Brown – who described himself as 'very hard up and a little mad' – was considering a move to India. The subject of his painting also suggests a feeling of being driven from a country which can no longer support its individuals, either financially or in legally protecting maligned identities.

There are repeated parallels between the film and painting through themes of escape. Indeed, Prospect Cottage hosted the filming of perhaps The Last of England's most iconic scene, where Tilda Swinton's character of the maid becomes a swirling frenzy of grief as she mourns her executed husband. With enormous scissors, she cuts into her wedding dress, tears it with her teeth, eats the delicate floral decorations before thrashing on the shingle shore, and becoming one with the flames of destruction in the background. The themes of violent consumption become overwhelming before she abandons it all, leaving the country in hope of a better life, emulating the couple within Brown's paintings. Swinton becomes a dynamic, furious something in the bleak landscape of nothing.

Much as the dreamlike, underworld haze of Jarman's England becomes hypnotically dangerous and beautiful, so Brown's churning background of waves suggest a picturesque but perilous past. The goodbye to England is bittersweet, Brown's couple is expressionless, neither exultant, relieved nor sad.

In Jarman's film, we feel a similar complexity of emotions. After the provocation and rebellion of the film, the maid provides a glimmer of hope, her turmoil shows valiant care for a hopeless situation, which we feel echoed in the rage of Jarman's activism. There is a defiance in waving goodbye which fights a strong urge to stay and try to reawaken a new future for the country.

In The Last of England, we see a fury that can only come from love and loss. Against the backdrop of the AIDS crisis and a government which was actively turning against its most vulnerable citizens, Jarman, despite his radical retellings and manipulations of time and convention, found stability in Prospect Cottage.

Caitlin Powell, London-based writer, art historian and comedian. You can find her all over social media and on her LGBTQ+ nostalgia podcast, Queers Gone By.