Tom Bogue, born in Edinburgh in 1860, was best known for his work in theatre.

His only known artwork remaining today (held since 1950 by the Ferens Art Gallery in Hull) is his 1913 painting of Whitby Moors.

By the age of 22 he was employed as an assistant artist at the Edinburgh Royal. He then moved to the Gaiety Theatre, Glasgow where his talents as a scenic artist became widely recognised. Special projects included a set of authentic models for a 'Grand Naval Review’, a semi-circular depiction of the Niagara Falls for a Panopticon in Sauchiehall Street and, for Moss’s Varieties in Edinburgh, an illuminated scene celebrating Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee that illustrated 50 years of industrial progress.

In March 1889, engaged by William Morton, manager of the Greenwich Theatre, to produce his next Christmas pantomime, he moved to south-east London. Designs would include sets, dresses and a dramatic transformation scene representing the four seasons. The move proved significant. In 1892, Bogue married Morton’s eldest daughter, Connie, and remained part of the family business for 46 years.

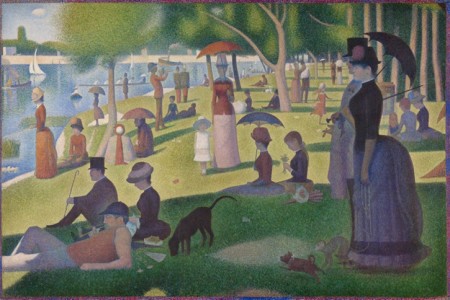

His art form was, by its very nature, ephemeral. A canvas 22 feet by 18 feet, with side flats, balustrades and 30-foot borders, might receive rave reviews and plaudits every night for a few weeks, but its life is limited. At best, it would go on tour for a few months, be sold on, or recycled. A good backdrop promised a slightly better future and, for the Greenwich Theatre, he created scenes of Venice, including Giudecca and the Jesuit Church.

In February 1895, Morton expanded the family business northwards and took on the lease of the Theatre Royal, Hull, appointing Bogue as resident artist. Although Bogue now had assistants and managerial responsibilities, he was still a busy hands-on artist. That December found him painting regularly until two o’ clock every morning. At that stage, Bogue was acknowledged as one of the foremost scenic artists in the country, and commissioned work – great and small – came his way. He built sets for a new theatre at Cleethorpes and took on contracts for several of the large touring companies. A highlight of Elaine Verner’s national tour with the popular play, ‘Saints and Sinners’, was Bogue’s elaborate depiction of Rodimore Woods. Local entrepreneur Anne Croft recalled how she once demanded that Bogue provide a real fountain for her set. He responded drily, ‘I will do my best, Anne, but I am afraid I cannot give you much of fountain, as your allowance for scenery and effects is only £2.’

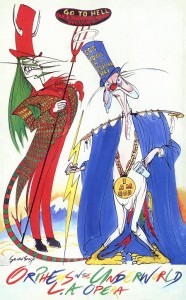

By 1902, Morton had made Hull his business centre. He built the Alexandra Theatre, and in 1907 purchased the Grand Opera House, both providing considerable scope for Bogue’s talents. In 1909, Bogue replaced his drop scene at the Alexandra with one of naval scenes that included his interpretation of Stansfield’s well-known picture of Trafalgar. The Era reported, ‘It is painted with fine spirit, and the artist has done himself justice in his conception and treatment of his subject’. It graced the theatre for over 20 years.

For a while, Bogue managed the Theatre Royal. In 1910, Morton commissioned Hull’s first purpose-built cinema, the Prince’s Hall, and Bogue became a director of Morton's Pictures.

Next, the company built the Holderness Hall, and then in 1915, the Majestic Picture House, where Bogue became permanent manager. In 1919, Morton acquired the Assembly Rooms. The family philosophy was to provide wholesome quality entertainment for ordinary people that embraced art, architecture, music, dance, theatre and cinema.

Towards the end of their 40-year dominance in Hull, the Morton family were hit by increasing difficulties in the film business and by the general decline in theatre-going. In 1935, unwilling to compromise standards, Morton’s businesses ceased to be financially viable. Bogue found new work as manager of the West Park Cinema until 1943 when, aged 83, he lost his wife and his home in an air raid.

He retired to the Glebelands Home, Wokingham in Berkshire, a residence for former workers in the cinema business. There he converted the summerhouse into an art studio. His paintings decorated the home and he exhibited some of them in art galleries. Even at 90, in 1950, the year before his death, he would spend eight to nine hours a day painting the people he remembered.

Peter Goodlad, researcher