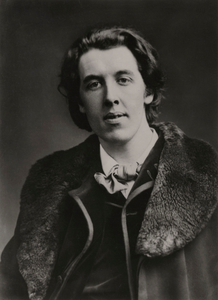

Oscar Wilde, the Irish writer known as much for his exuberant wit and aestheticism as for his work, was deeply invested in his public image. 'I've put my genius into my life; I've put only my talent into my works,' he explained to French writer André Gide.

Wilde's 'genius' for living made him an icon of the Aesthetic movement, which championed beauty over utility, or art for art's sake. But his hubristic joie de vivre also played a part in his downfall in public opinion.

His reputation as a celebrated playwright soured after he unsuccessfully sued his lover's father, the Marquess of Queensberry, for libel in 1895. (The Marquess' infamous calling card accusing him of being a 'somdomite' even misspelt the slur, adding insult to injury.) Wilde was instead found guilty of 'gross indecency' and sentenced to two years in prison for having sex with men. He emerged bankrupt, in poor health and shunned by the society that had once fêted him; he immediately left England and travelled restlessly through Europe until his death in 1900, aged 46.

Wilde achieved his stated aims of 'success; fame or even notoriety' in his lifetime, which have continued into the present. His personality was crystalised in contemporary photographs, caricatures and portraits that perpetuated imagery of both the man and the myth, 'who smoked gold-tipped cigarettes and who walked about in the streets with a sunflower in his hand', as Gide described. Wilde knew how to project a scintillating character that ensured his legacy would live on.

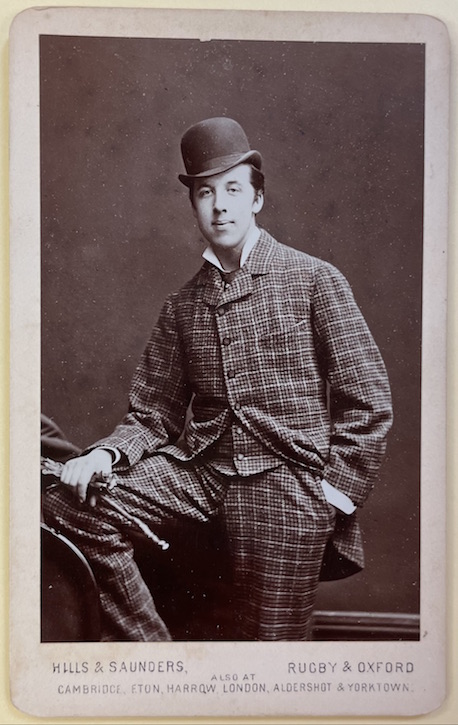

Oscar Wilde, 1876

William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, UCLA

Wilde's youthful adoption of Aesthetic ideals and tongue-in-cheek approach to life were both embodied in his famous remark at university, that he wished he could 'live up to his blue china'. A photo of him as a student at Oxford, where he studied after Trinity College Dublin, shows him confident and dapper in a checked suit and jauntily tilted hat.

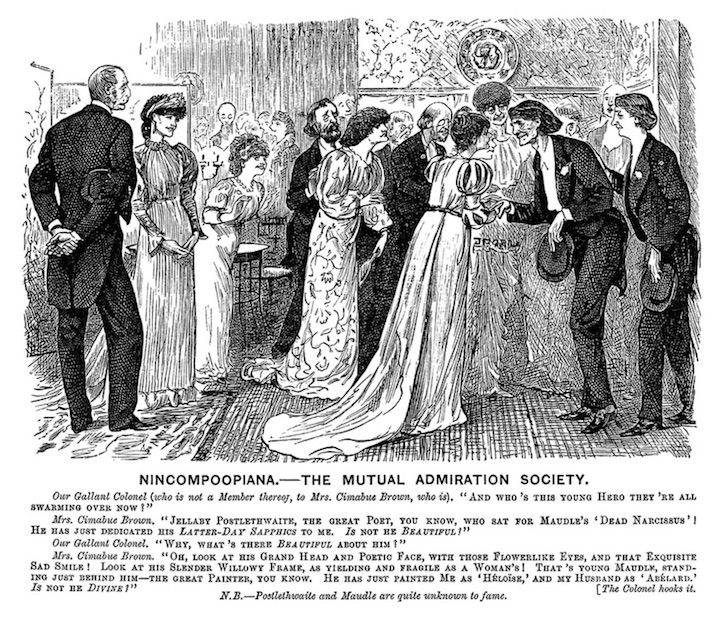

Nincompoopiana – The Mutual Admiration Society

1880, cartoon by George Du Maurier (1834–1896), 'Punch'

In 1880, George du Maurier began including a character called Jellaby Postlethwaite in his caricatures for the popular magazine Punch, which mocked the Aesthetic movement's followers, including Wilde, who was quick to latch on to even negative publicity to make his name. This example depicts an 'aesthetic mid-day meal' as a delicate lily to criticise the movement's lack of substance and perceived effeminacy.

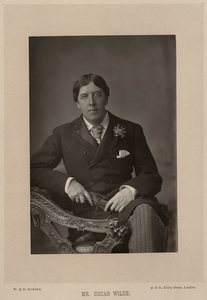

In the late nineteenth century, photography was taking hold as an increasingly popular and affordable medium. As an aesthete who gave great credence to appearance, Wilde was photographed throughout his life, creating easily distributable images that would further his literary and artistic reputation. This 1881 cabinet card by Elliot & Fry would have been circulated among friends and social circles, establishing the young writer's image and style.

In 1882, producer Richard D'Oyly Carte sent Wilde on a year-long lecture tour around America to drum up interest in Gilbert and Sullivan's satirical send-up of the Aesthetic movement, Patience. Wilde's showmanship teased, shocked and charmed audiences – he was frequently derided in the press, but the tour successfully established his celebrity.

Wilde's portraits by famous New York photographer Napoleon Sarony were intended to cement his dandified image, sold in multiple sizes at his lecture stops on the tour.

They have since become some of the most recognisable images of Wilde – especially those in pensive, lounging poses, suggesting the tortured artist at work. In the photographs, Wilde is costumed in elaborately aesthetic outfits, including this one consisting of a smoking jacket, knee-breeches, and pumps.

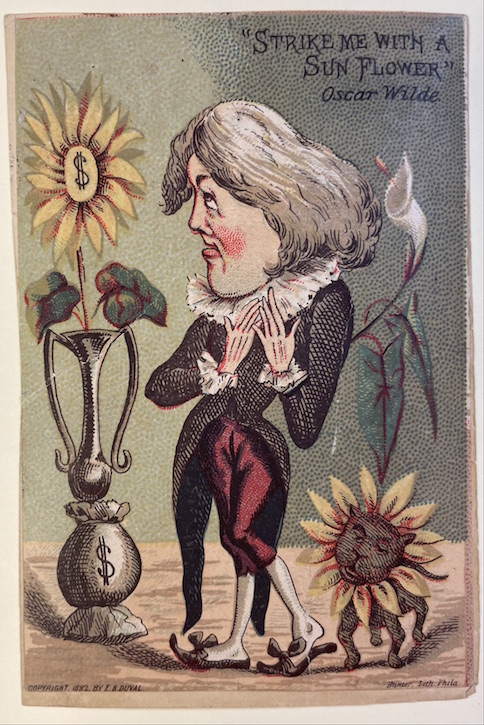

Wilde's eagerness to be the poster child for Aestheticism saw him frequently associated with the sunflower – one of the movement's symbols – along with the lily. E. B. Duval's colour lithograph from the American tour shows Wilde standing in an affected pose between both flowers, while the dollar signs within the sunflower and on its silver vase suggest the movement's ideals were unaffordable as well as impractical.

'Strike me with a sunflower'

1882, colour lithograph by E. B. Duval. William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, UCLA

In 1884, Wilde married Constance Lloyd, with whom he would have two sons. His sketch in an issue of Vanity Fair from the same year shows his establishment in English society as well as his continued commitment to aesthetic attire.

Wilde's later photographs, like this one from 1889, aimed to further his reputation as a respected writer with poses of increased gravitas. Still, he retained his characteristic sartorial flair through the flower on his lapel.

In 1891, Wilde published his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray and met Lord Alfred Douglas, known to friends as 'Bosie'. They soon began a capricious and volatile relationship that would lead to Wilde's public vilification and downfall.

Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Bruce Douglas

1893

Gillman & Co.

In the same period, Wilde was writing the drawing room comedies that would make his name as a playwright: Lady Windermere's Fan (1892), An Ideal Husband (1895) and The Importance of Being Earnest (1895). The plays layered witty frivolity with an astute skewering of hypocritical social mores.

As Wilde's fame and fortune rose, so too did his risk-taking behaviour: Bosie introduced him to young male sex workers, and his then-illegal liaisons became more dangerous in light of his public profile.

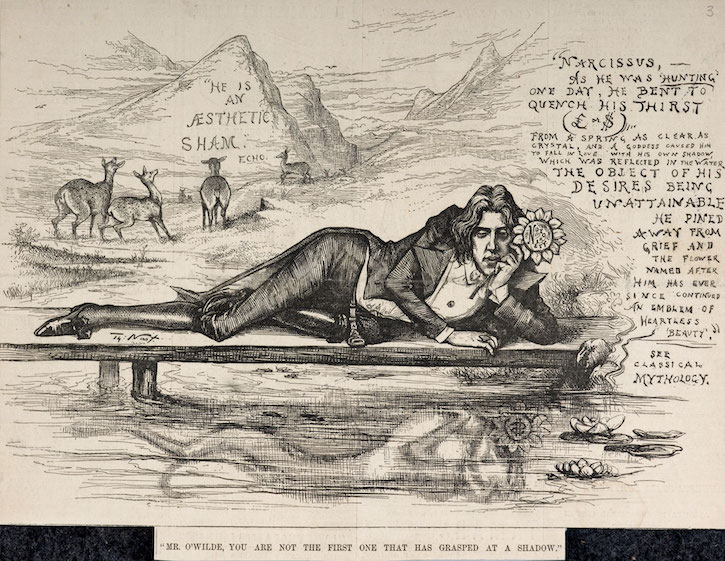

While Wilde had been something of an Aesthetic lightning rod since stepping into the public sphere, Thomas Nash's 1890s caricature showed that his notoriety was increasing (by, somewhat obviously, labelling a sunflower with the word).

Caricature of Oscar Wilde as Narcissus

cartoon by Thomas Nast (1840–1902)

The image attacked Wilde on multiple fronts: lampooning Wilde's public persona by depicting him as the self-obsessed Narcissus of Greek myth, deriding his Irish roots by referring to him as 'O'Wilde', and denigrating his career by calling him an 'aesthetic sham'.

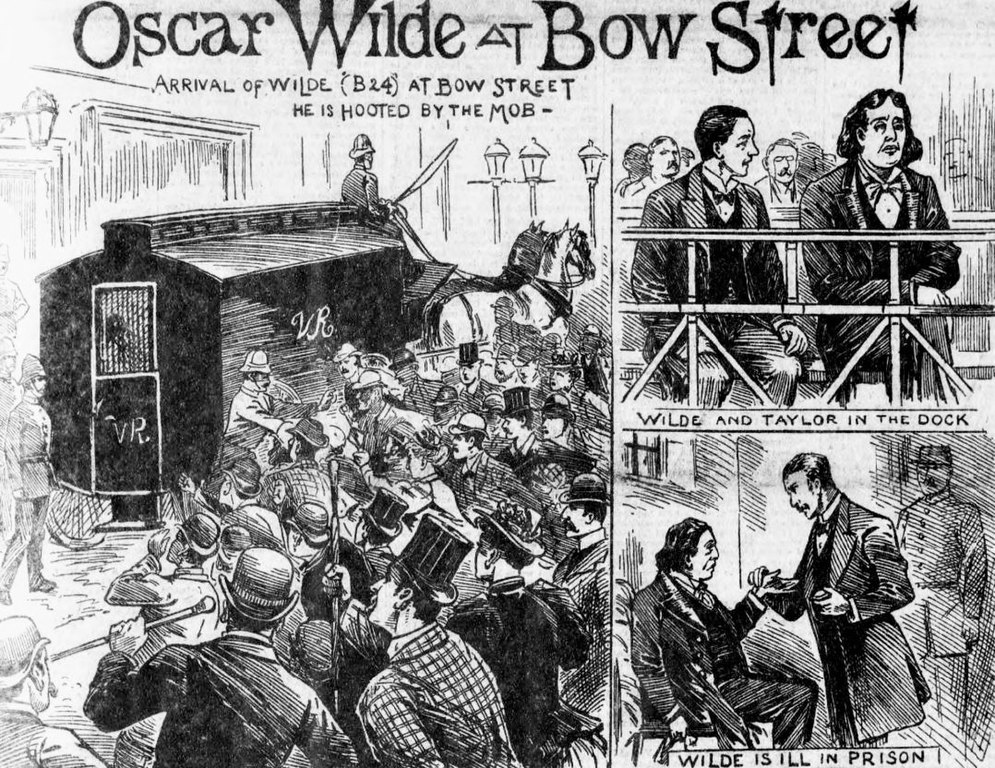

If Wilde's image was already notorious, his trial – brought about by the testimony that emerged in his case against the Marquess of Queensberry – irrevocably tipped the scales. The salacious press reports shut and bolted the doors of society to him: one caption labelled him 'the rankest weed in London's garden of scandal and filth'.

Some contemporary illustrations seemed to revel in Wilde's downfall, depicting him being 'hooted by the mob' and sitting defeatedly in the dock and in prison.

Scenes from the trial of Oscar Wilde

1895, 'Illustrated Police News'

Sentenced to two years of hard labour, Wilde wrote his soul-searching letter to Bosie, De Profundis, while incarcerated, and later the compassionate The Ballad of Reading Gaol. The law that Wilde was sentenced under had been established in 1885 – it wasn't until 1967 that sex between men was partially decriminalised in England and Wales, and fully in 2003.

With his image in tatters, Wilde spent the last few years of his life after his release from Reading Gaol as an outcast, far from the public eye. But in 1997, nearly a century after Wilde's death, he was commemorated with a first public sculpture in his birthplace of Dublin.

Statue of Oscar Wilde in Merrion Square, Dublin

1997, sculpture by Danny Osborne (b.1949)

Danny Osborne's camp statue reclines on a boulder in Merrion Square Park, wearing a smoking jacket and a smirk. The pose and outfit recall several aspects of Wilde's iconic Sarony portraits, showing the impact of Wilde's carefully cultivated image decades later.

Another public tribute followed in Westminster the following year, intended to spark 'a conversation'. Maggi Hambling's bronze, scribbly featured Oscar emerges with a cigarette from a coffin-shaped granite bench emblazoned with one of his most famous phrases: 'We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.'

A Conversation with Oscar Wilde

1998

Maggi Hambling

The tilt of the head and hand convey a recognisable Wildean dash as he looks up at the viewer, or the sky.

As recently as 2021, street artist Banksy painted the wall of Reading Gaol with a man escaping on a sheet of knotted typewriter paper as a homage to Wilde.

Though the sunglasses-wearing figure is not intended to look like Wilde, it illustrates how his persona continues to be adapted into commentary on the inequities of the past and possibilities for the future: there is an ongoing debate about whether the now-empty Gaol will be repurposed into an arts centre.

Today, Wilde's reputation encompasses his wit, his talent and his fatal flaws, all of which have contributed to his enduring status as a queer icon who lived flamboyantly and endured ruthless discrimination.

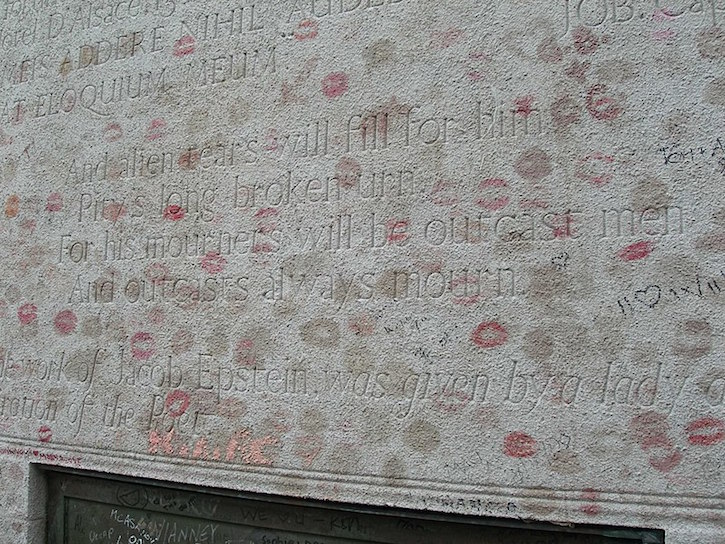

Oscar Wilde's tomb in the Père Lachaise cemetery, Paris, in 2012

unveiled 1914, Hopton Wood stone by Jacob Epstein (1880–1959)

In 1909, Wilde was reinterred in Paris' Père Lachaise cemetery in a tomb commissioned from sculptor Jacob Epstein by Wilde's friend and lover Robbie Ross, whose ashes were also placed there. In a fittingly flamboyant tribute, visitors began leaving lipstick kisses at the tomb, to the extent that a barrier was erected to preserve the stone – which was being eroded by the animal products in lipstick – in 2011.

Verse on the back of Oscar Wilde's tomb, 2009

Wilde's epitaph, taken from the Ballad, states that 'his mourners will be outcast men, and outcasts always mourn'. There is still much to mourn and work towards in achieving equal rights for LGBTQ+ people around the world. Still, in a gesture of celebration and defiance, people kiss the glass.

Anne Wallentine, writer, editor and art historian

Enjoyed this story? Get all the latest Art UK stories sent directly to your inbox when you sign up for our newsletter.

.jpg)