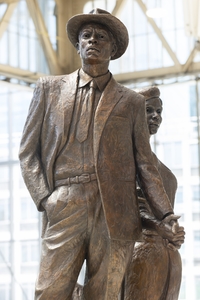

The selection of Jamaican, USA-based sculptor Basil Watson to create the National Windrush Monument commission is inspired.

The National Windrush Monument

2022

Basil Watson

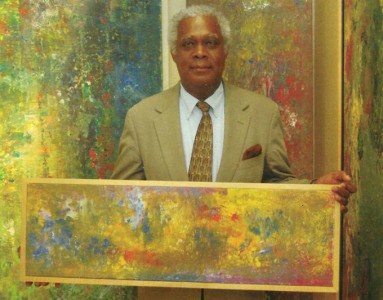

Watson is a part of a three-generation dynasty of artists who are known as the 'Jamaican royal family' of artists. Barrington Watson, Watson's father, was an esteemed artist in his own right, his three sons are also artists, and Basil Watson's son, Kai, is following the family tradition of creating art in the studio he shares with his father in Georgia, USA.

The Windrush migration story is the Watson family story. It is also the story of many people like them. The Watson family lived in the UK for about a decade in the 1950s and 1960s – they travelled from the Caribbean with similar suitcases to those depicted in the sculpture. This sculpture – a cast in bronze – is both personal and global for the creator Basil Watson. The National Windrush Monument will be situated in Waterloo Station, London from 22nd June 2022, unveiled on the fifth national Windrush Day in the UK.

The National Windrush Monument

2022

Basil Watson

I caught up with Basil Watson – who was at the Stroud foundry where he was completing his work on the sculpture – to discuss his life, and this monumental work made in honour of the Windrush generation of the UK.

Marjorie H. Morgan: On your website, you state that art is 'the harmonious expression of one's vision and life'. Can you explain that quotation?

Basil Watson: I think it's more than just one's talent or ability to depict things, but how you put the story together, and I think that one's view of life needs to be in harmony with reality and with life in general.

The National Windrush Monument

2022

Basil Watson

Marjorie: What particular emotional expression are you communicating through the Windrush Monument commission?

Basil: Everyone has an expression, but it's how you put your ideas together that resonates with people; in order to get the reaction or the response it should be put together in a harmonious way where your message is arresting and catches the attention.

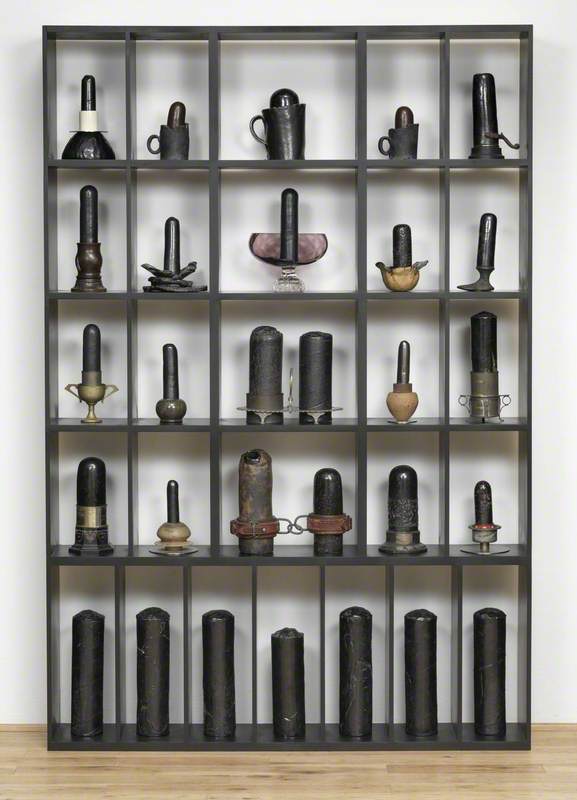

The National Windrush Monument

model by Basil Watson (b.1958)

Marjorie: What features in this sculpture, do you think, will achieve that aim?

Basil: There are certain messages that I want to put across. Firstly, the composition of the family – three figures. Secondly, the other major components are the suitcases, and the symbolism behind the suitcases.

The National Windrush Monument

2022

Basil Watson

Then within the composition of the figures, there are elements of the man and woman holding hands, the skirt touching his leg, and the posture of each individual in the composition: the woman is the one with both hands engaged – she is holding the man while nurturing the child. The man is holding the woman while looking ahead, the child is looking back thinking introspectively about her journey while still being in contact with her mother.

The National Windrush Monument

2022

Basil Watson

I want these conceptual elements to resonate with people, and capture the imagination about what the family is, how the family works, and the dynamics of the family that came into the society.

The structure of the family is changing dramatically but there are still certain traditional things that are difficult to get away from. The suitcases hark back to a time when we had these reinforced corners – these things I want to use to arrest the attention, and encourage people to reflect: on themselves, and on their history.

Marjorie: You are a Jamaican who resides in Georgia, USA, and you're creating this structure for installation in London in the UK. How do you think that these personal global connections have influenced your creation of this piece?

Basil: The world is becoming a global village. We are a migratory species, and we are moving to a time where we are developing a global culture. It's very much the case that everyone is influencing each other. The monument design talks about any culture, any set of people. We see today the Ukrainians – different suitcases, different clothing, but the journey is very similar. We have seen different communities make these journeys over recent history, and it is something that has been happening forever.

I had that migratory experience 20 years ago. I lived my conscious early life in Jamaica. When I left the UK, when my whole family moved back to Jamaica in 1962, I was four years old. I remember nothing about it, I've never been back since – but when I was in my 40s I decided to migrate to the United States, and went through a lot of the same emotional journeys that my parents would have gone through. I think it is a very familiar story for most people.

Marjorie: Many members of the Watson family are well known as artists, how do you feel about that?

Basil: My father [Basil Barrington Watson] had three children, and we are all artists. My brother (Raymond Watson) has a public sculpture in Brixton. He lived here for a while in the 1990s and worked here as an artist and a sculptor. Then he decided that he wanted to go back to Jamaica, so it is somewhat of a family tradition.

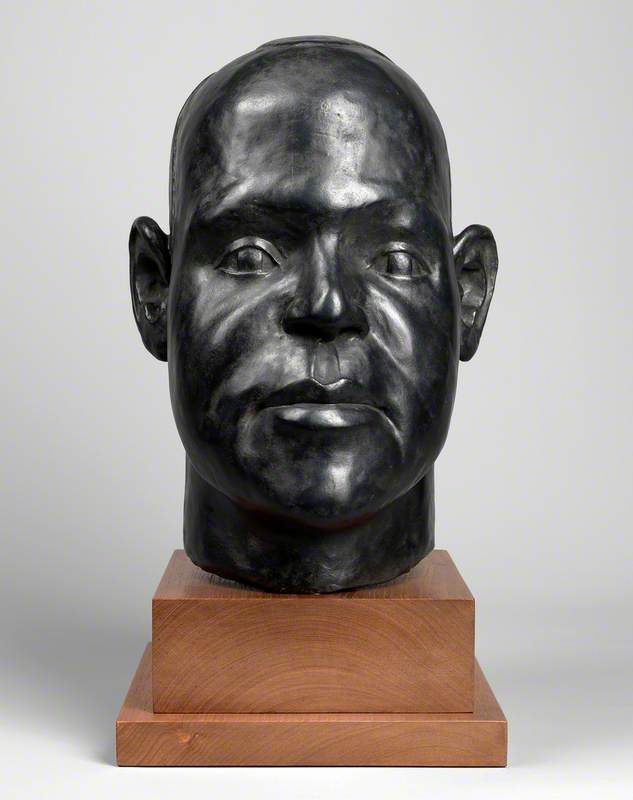

Marjorie: Looking at your public sculptures I noticed a recurring theme – a series of heroes, and I also read that you are 'inspired by the heroic in mankind'. You've created sculptures of people including Martin Luther King Jr, Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce, Usain Bolt and Asafa Powell. How do you think the Windrush family in The National Windrush Monument fit into the hero category?

Basil: I think they fit very well into the hero category. I look at the heroic aspect of their journey. The courage that it takes. In today's world, we are constantly in touch by social media. I can only imagine leaving home, sailing on the sea for three weeks, going to a place that you only hear about, not connecting with your family for the months at a time that a letter takes. It took a lot of courage to do that. And they all went out, without exception, seeking advancement, with the aspiration to ascend and move forward.

In my father's situation, I wonder what allowed him to feel that he needed to follow this path of being an artist. That sort of vision and journey is all heroic. This was his journey but there were others who had similar aspirations, and they are very much heroes in terms of what they have achieved.

Marjorie: This sculpture is a worthy monument to your forebears and many others as well, who created a new reality. They had a dream and set out on their journey. What do you think is the potential legacy of your creation of this piece?

Basil: I want people to get a little better understanding of life, of themselves, of society, to connect, to be reflective of what makes us all brilliant, what makes us strong, what makes us beautiful. I decided, a long time ago, that I look to the light. There's no point looking into the darkness. It is those luminaries before me that have motivated me and I enjoy expressing myself in art. If I'm going to spend hours on a sculpture it must give me this feeling of exploring the light, exploring the heroic in man. Hopefully, if people see that then I am doubly blessed because I'm blessed just to be able to do it for myself.

Marjorie: With regard to your practice, do you start with a maquette before the final piece? What are the dimensions of the finished sculpture?

Basil: It usually follows that progression. With the maquette, you can toss it around, in many different directions quickly. In the large-scale piece, it needs concrete planning in order to operate at that level. The sculpture is about 12 feet tall. The male figure is the tallest of the figures themselves, he's about 8 feet, and they stand on a pile of 4-foot-high suitcases.

Marjorie: Your father dreamed of being an artist. You've followed in his footsteps, and maybe even exceeded his reach because you've had your sculptures in international locations such as Guatemala, Changchun Sculpture Symposium, and now in the UK. Where do you think you'll go next?

Basil: To my studio. That's where it all starts. With dreams.

Basil Watson at work

Marjorie: You migrated to the US in 2002 – did you dream of living abroad when you were younger?

Basil: When my father lived abroad, he made a conscious decision to go back to Jamaica. He always spoke about Jamaican art being in Jamaica and bringing people to Jamaica to see it, and I grew up very much with that sort of idea, and I was comfortably making art in Jamaica. But I felt I needed a bigger platform, so I made the decision to move abroad, mainly to get my work on a larger scale. The journey abroad was necessary for my personal growth.

Marjorie: This large-scale sculpture in Waterloo Station is quite monumental to acknowledge people here in England, especially with what's been going on with the Windrush scandal. I know from personal experience that British people with Caribbean roots seeing what you've created will mean a tremendous amount. From me, and them, I just want to say thank you for this sculpture.

Basil: You're welcome. I should also say thank you. Wherever we are, out there always seems a little bit bigger. I don't think I really appreciate the impact this sculpture is making and this is one of the reasons why I thank my parents for going back to Jamaica. I think living in Jamaica has been a tremendous foundation for me spiritually as well as in other ways. People need to feel like they can actually attain the highest goals possible, and every experience contributes to that growth.

The National #WindrushMonument is here.

— Department for Levelling Up, Housing & Communities (@luhc) June 22, 2022

Unveiled today on #WindrushDay it is a significant symbol honouring the contribution of the Windrush Generation standing proudly at @LondonWaterloo. #WindrushDay2022 | https://t.co/jes2em7mQn pic.twitter.com/leVHYwqvh1

Marjorie: The National Windrush Monument in Waterloo Station gives a sense of permanence for British Caribbean people. Thank you again for all you've communicated in this sculpture.

Basil: I want to thank the British descendants of the Windrush generation for the work, the effort, the resilience, the strength that they have shown. They could have gone under decades ago but they have risen to the point where they have created this perfect storm for me. I appreciate their life and I am very thankful that I have been given the opportunity to make this monument to express their aspirations because without them succeeding I would not be here today. The National Windrush Monument is my thank you to them all.

Marjorie H. Morgan, playwright, director, producer and journalist