The release of Margy Kinmonth's cinema documentary, Eric Ravilious: Drawn to War in July 2022, has brought this artist once more into the news. Timed to coincide with the 80th anniversary of his accidental death when serving as a war artist, it is a rare example of a full-length biopic of an artist some have considered minor or marginal, although, for a so-called 'forgotten' artist, he has collected an increasing and dedicated fan-club.

Eric Ravilious

Still, somehow, Eric Ravilious (1903–1942) doesn't quite fit into the mainstream narrative. Too easy to like? Not a pioneer in style? A decorator and designer as much as a 'fine' artist? All these are held against him. Yet it is his Train Landscape (1939) that features on the cover of Frances Spalding's new survey of British art between the wars, The Real and the Romantic – he sells books, whatever else we think of him.

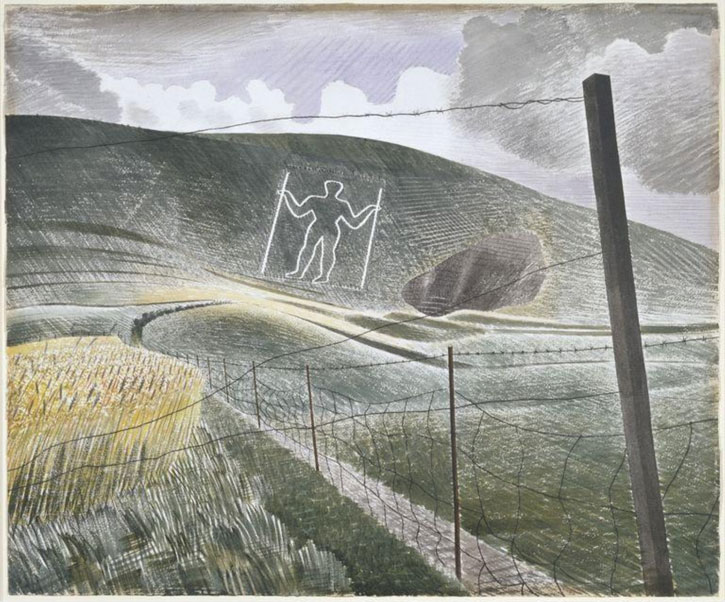

Alan Bennett recalls in the film how he discovered Ravilious through a reproduction Train Landscape in a school classroom in the mid-1940s. The watercolour painting formed part of a series of 'Chalk Figures' completed after his last one-man show in the spring of 1939, and although never formally exhibited, the Leicester Galleries in London arranged for the sale of three of them into public collections.

Train Landscape is as quintessential a Ravilious painting as you could find, with its combination of a hillside chalk figure (in this case, the Westbury White Horse) and the third-class railway carriage with its patterned moquette, bold numeral painted on the door and general sense of a frozen moment between the ancient world and the modern one, bathed in a serene light, rendered through meticulous and complex overlays short brushstrokes and underlying unifying areas of tone.

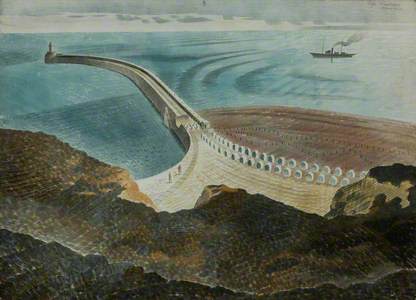

The Long Man of Wilmington

1939, watercolour on paper by Eric Ravilious (1903–1942)

Train Landscape was bought by Aberdeen Art Gallery in 1940, while the V&A bought The Long Man of Wilmington (which features conspicuously in the film) and John Rothenstein at the Tate bought The Vale of the White Horse, perhaps the most visually adventurous of the set. Not a bad score for a forgotten and neglected artist. The snag, however, is that because almost all his major surviving work is in watercolour on paper, it can only be displayed under light conditions more demanding than those for oil paintings, so it is never there to line up with Stanley Spencer, Christopher Wood or the early Victor Pasmore.

The Vale of the White Horse

1939, watercolour on paper by Eric Ravilious (1903–1942)

By 1940, Ravilious had begun his prolific but abbreviated career as a War Artist. Since all the work produced by the scheme belonged to the government, this represents his largest set of publicly held pieces, including many in which he successfully coped with new subjects, often involving the human figures he had previously tended to ignore.

The great majority are held by the Imperial War Museum, although some were distributed to art galleries in different parts of Britain and in the former Empire.

Thus, for example, the Ashmolean in Oxford holds Ship's Screw on a Railway Truck, painted at Chatham in the second winter of the war.

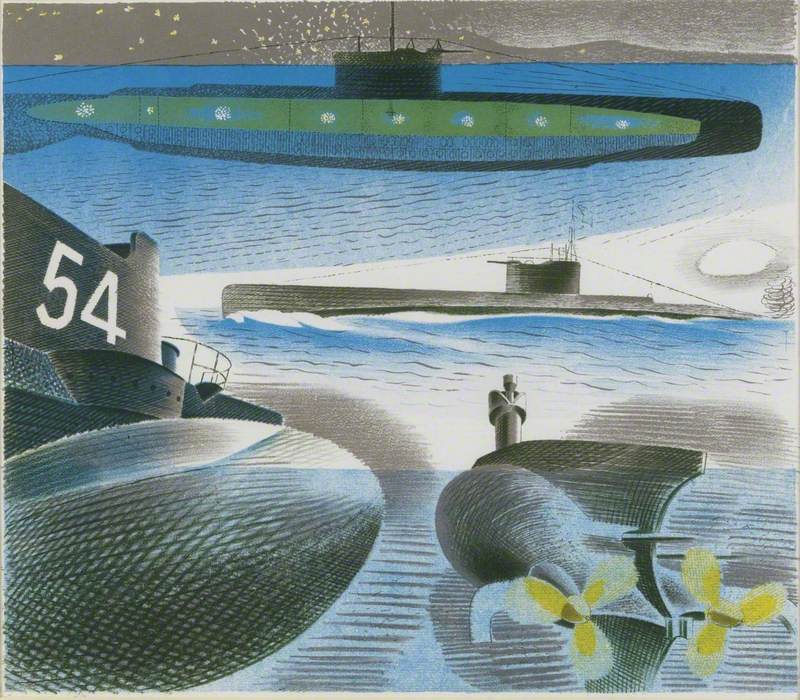

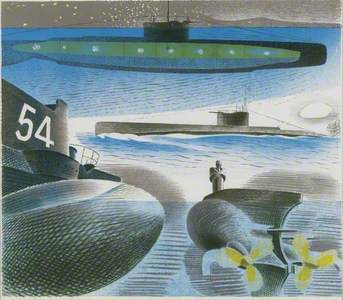

Here his instinct for the innate symbolic quality of objects and their strangeness has full play, as well as his fondness for snow and night skies. Ravilious became fascinated by submarines and spent time on board one of them to prepare lithographs for a projected book. Although relatively small numbers of these seem to have been printed, they are striking images, conveying the domesticity of life as well as the discomfort and danger.

Ravilious held three one-man shows in the 1930s, modestly priced and quickly sold out, as well as exhibiting in a few group shows. The majority of his paintings, therefore, went into private collections where some remain unseen to this day. Since his rise to fame, and as the generation of the original purchasers passes away, these have increasingly entered the market, together with work that remains unsold at the time of his death, and a considerable number have gone into public collections.

Drawn to War reveals that the work he left when he died was stored by his great friend Edward Bawden underneath a bed at his home in Great Bardfield until restored to his three children in 1972, the year of the first retrospective since his memorial exhibition.

Much of this treasure trove has gradually entered the market to support his three children and their families, often on generous terms for public institutions, and this has inspired further gifts. The Towner in Eastbourne, the town where he grew up, has become the major centre for his work, with a secondary focus at the Fry Art Gallery, Saffron Walden.

Tea at Furlongs (1938) in Fry Art Gallery is singled out by Alan Bennett for its sense of calm before the storm – 'It could be called Munich 1938' he says. People read things into Ravilious paintings and they may not be wrong, but I don't think there can be one single correct interpretation for any of them. I have sat at a table in the exact place shown in Tea at Furlongs, being entertained by Ravilious' friend Peggy Angus.

It is exactly as shown, yet I think Ravilious must primarily have chosen subjects that worked for him as suggestive spatial compositions with a particular play of light. The objects and buildings in them were 'as found', and in this way certainly added a mood, just as they had done for other painters for centuries. A perfectionist, if he started a subject that didn't satisfy him, he usually tore up the paper – four times out of five, according to his wife, the artist Tirzah Garwood.

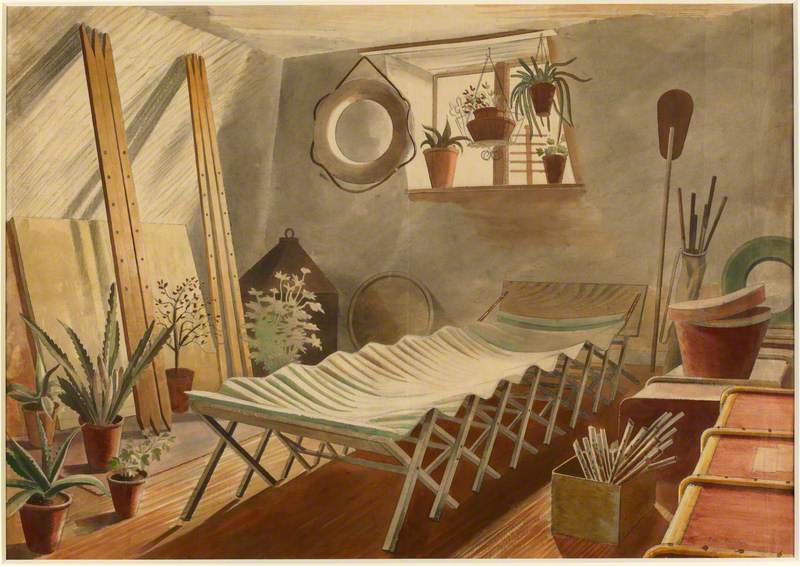

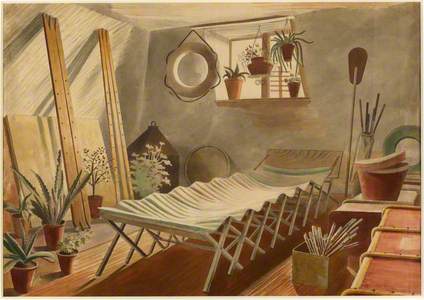

The Attic Bedroom (1933) must also have been 'as found', but not every artist would pick such an apparently unpromising subject and make it both formally a fascinating play of shapes and angles, and additionally a slice of seventeenth-century emblem culture – a sort of metaphorical desert evoking the absence of water through its stranded aquatic impedimenta, plus cacti.

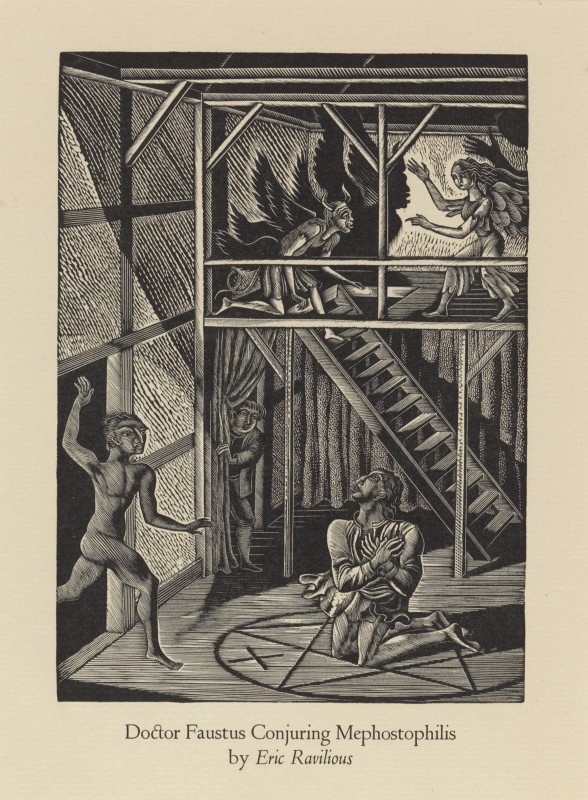

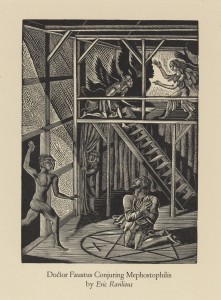

It is in Ravilious' wood engravings more than his paintings that we can experience his poetic side. Dr Faustus conjuring Mephistopheles, 1928, from Christopher Marlowe's play, evokes the Elizabethan stage, fully relishing the drama but making his devil a rather sexy male nude. What hope now for Faustus' good angel battling on the upper stage level?

Literature, music and songs of the Tudor and Jacobean period were in vogue, and helped to lead artists from T. S. Eliot to Michael Tippett away from the lushness of the Victorians to a leaner mode of expression.

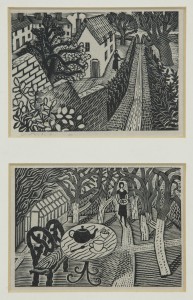

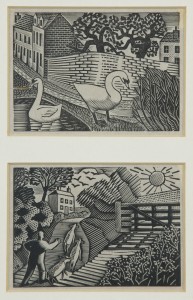

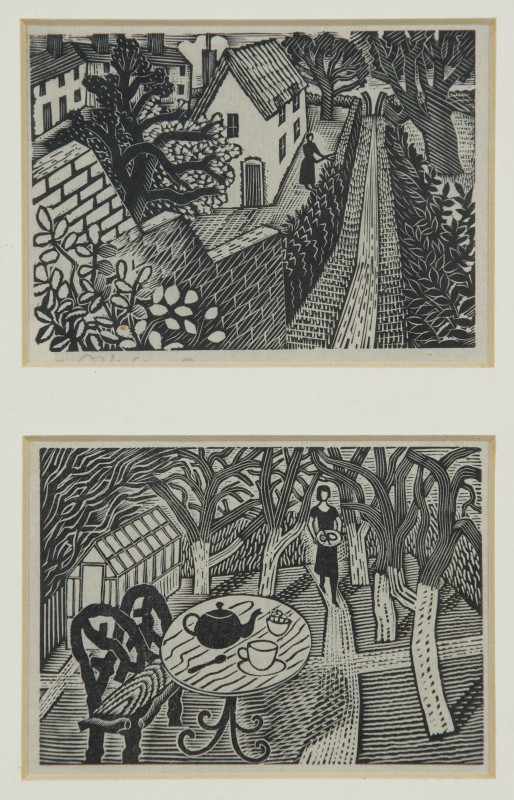

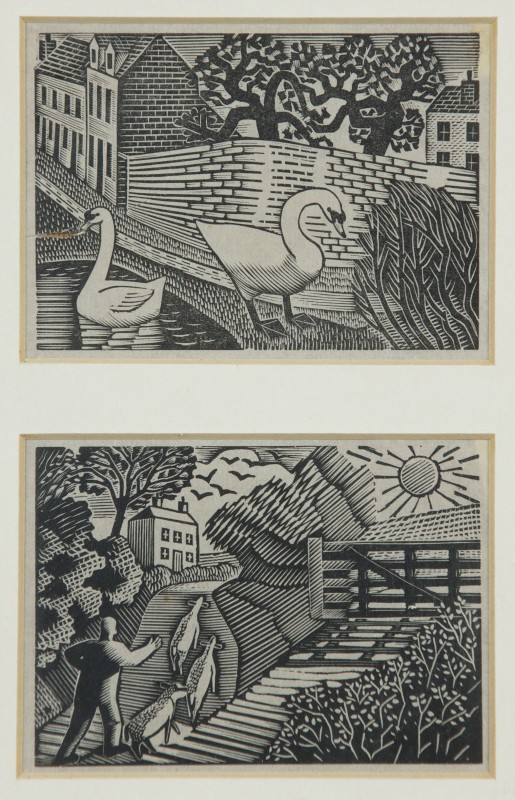

The engravings for London Transport's Country Walks booklets, among his most widely-distributed images over several decades, are apparently simple evocations of place, but the one showing a shepherd taking his flock of three up a lane simply fizzes with graphic ingenuity within the limits of the medium he understood so well.

Designs for London Transport

(2 of 4)

Eric Ravilious (1903–1942)

In terms of literal representation, everything is wrong in scale, tonality and perspective, but this is Cubism for the masses, tuned to a point where a general public knew how to read the image and, one hopes, get a kick out of it.

Designs for London Transport

(2 of 4)

Eric Ravilious (1903–1942)

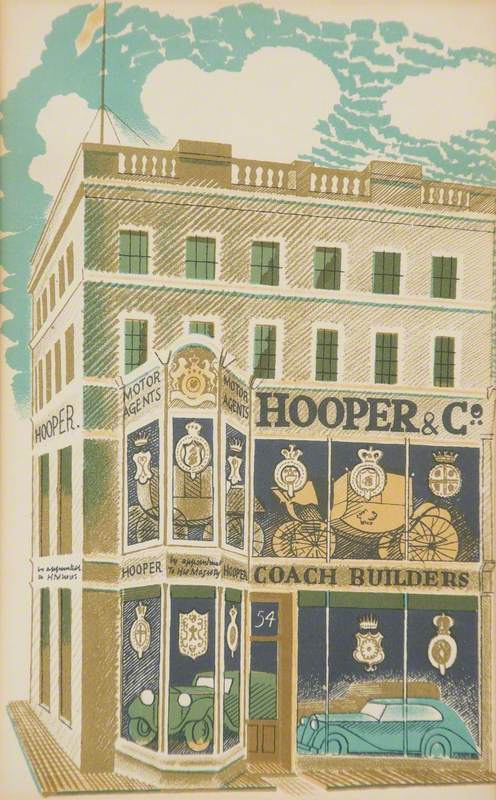

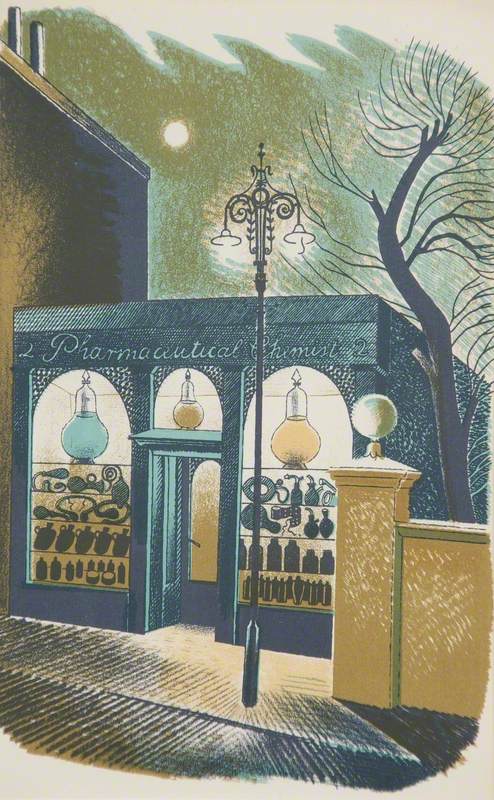

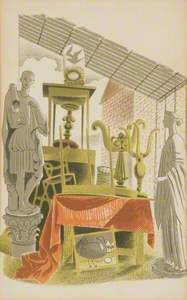

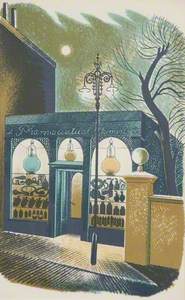

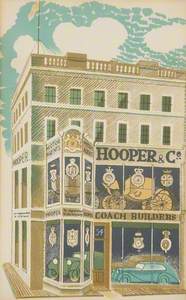

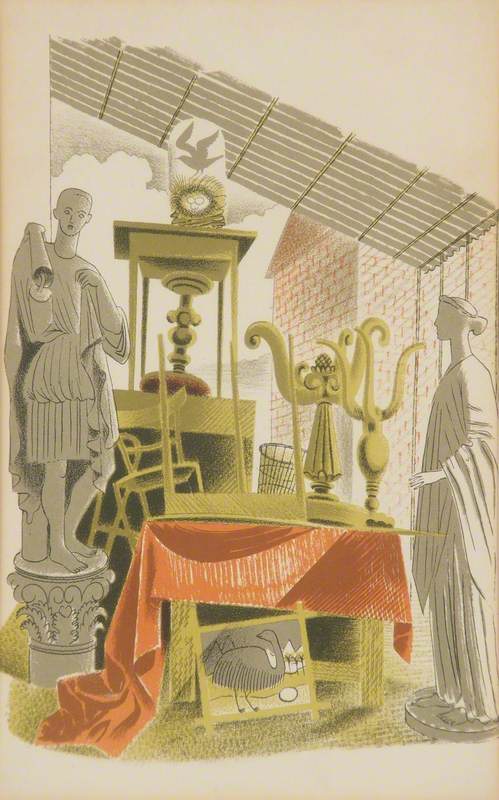

By this date, Ravilious was increasingly interested in lithography as an alternative print medium. Apart from the Submarines, never widely distributed, a wider public would have known High Street, 1938, a book with 21 prints of the insides and outsides of shops, whimsically chosen and showing hardly anything to represent the previous ten or twenty years. He learnt how to use a limited number of separately drawn colours overlaid to produce the image.

Second-Hand Furniture and Effects

1938

Eric Ravilious (1903–1942)

Where shall we go shopping today? To Second Hand Furniture and Effects, reminiscent of his father's trade as an antique dealer – who would have thought upturned legs of a pedestal table so octopoid? Or to the nocturnal Pharmaceutical Chemist, offering the comfort of coloured liquid in giant vials to the residents of some gently decaying inner London suburb?

In the years leading up to his death, Ravilious told his friends how dissatisfied he was becoming with his work. It was a form of mid-life crisis, no doubt, that he could have resolved had he lived longer, yet the curtailment of his life places him precisely within an epoch. If we take the title of Frances Spalding's book, he contrives to be both Real and Romantic simultaneously, yet the romanticism is all the stronger for its understatement and its anchorage to realism.

Alan Powers, art historian and author of Eric Ravilious, Artist and Designer