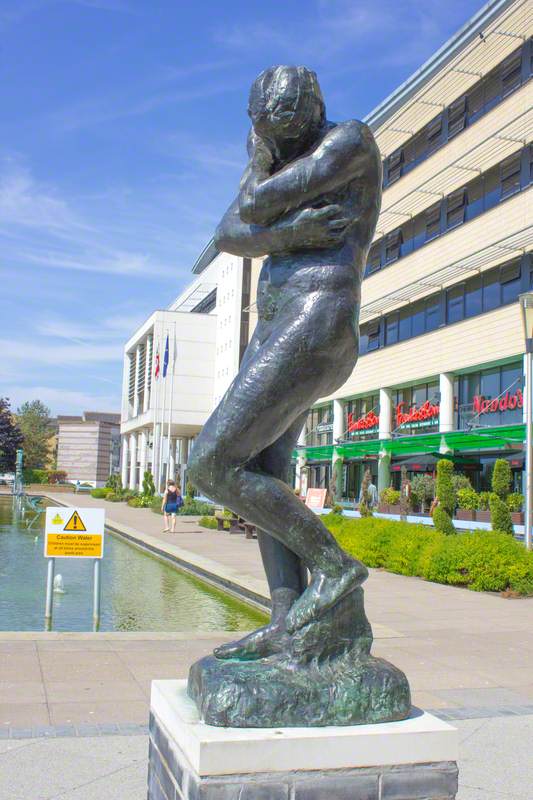

Art UK's Gemma Briggs spoke to sculptor Denise Dutton about the creation of a prominent new public sculpture, unveiled on Anning's 223rd birthday.

Mary Anning was just 12 years old when, in 1811, she found the first complete ichthyosaur to be discovered in England, one of many important palaeontological discoveries that would go uncredited due to her gender and class. It is fitting that the campaign to see Anning's achievements finally recognised in her hometown of Lyme Regis has been led by a local schoolgirl, Evie Swires.

Evie's campaign led to the creation of the Mary Anning statue

'I started this campaign because I was really angry that Mary wasn't remembered in the town where she was born,' Evie, now 14 years old, tells us. 'We did a project at school when I was 10 and we found out that only 3% of statues in the UK are of women and most of them are Queen Victoria. I wanted Mary to be remembered in the town because she is amazing. My mum always says, "you can't be what you can't see". If we are looking at white old men on pedestals all day it is not very inspiring for girls like me, is it?'

With such an impressively determined client, the task of imagining Anning from just one contemporary painting was not going to be easy.

The challenge fell to Stoke-on-Trent-based sculptor Denise Dutton, and for good reason – she had already created memorials to the Lancashire suffragette Annie Kenney, and the Women's Land Army and Timber Corps. Recognising the triumphs of unsung female pioneers is becoming her speciality.

I visited Dutton in her Stoke studio the week before the Mary Anning Rocks! unveiling. The pair of rooms on the upper floor of a historic former dye works are edged with a jumble of materials and tools.

Bust of an academic in progress at Denise Dutton's studio

There is work in progress (the smiling bust of an academic) and the remnants of work now complete: the full-scale clay model of Anning, post-casting, pockmarked by chisels and missing her hands.

The clay model of Mary Anning in Denise Dutton's studio

Dutton is wearing a well-washed campaign t-shirt that reads, 'Mary Anning: mother of dragons, breaker of rocks, Lyme Regis-born paleo pioneer'. As we begin to talk, she enthusiastically pulls out books and finds detailed photographs on her phone. It's clear she has read every scrap of source material to understand not just her subject, but Anning's subjects, too. Fizzing with enthusiasm, she explains that the ammonites featured across the sculpture are the correct size and species for those found in Lyme Regis (Eoderoceras, if you are also a fossil enthusiast).

Denise Dutton in her studio

Anning and her contemporaries were working during a time when many scientists believed these creatures were still alive, and Charles Darwin's On The Origin of Species would not be published until over a decade after Anning's death. 'Mary was starting to understand that there were different species of ichthyosaur and that's the thing that amazes me about her,' says Dutton. 'When I studied anatomy, I went down to the veterinary college in London and sat in on dissections, but Mary had nothing like that. When she found these bits and pieces on the beach, how did she know how to put them together?'

She points to the female skeleton standing in the corner of the studio: 'If you were given a jigsaw of that skeleton, you'd be hard pushed to make sure you got everything in the right position; it is so difficult. It fascinates me. In her time it would have been an odd thing for her to be doing, but she was of a lower class so she could go out on her own; she didn't need someone with her.'

The model of a skeleton in Denise Dutton's studio

Perhaps it is this shared fascination for animal anatomy – Dutton has sculpted several horses, as well as the dog that walks alongside Mary – that explains the affinity for her subject and commitment to achieving a likeness with little more than a distinctive nose to go on. 'You can find yourself modelling the same face, you get a formula, but I do not like that. The way a face is made up is fascinating, you study the bones and the muscles. It's a constant assimilation of information I get from life drawing.'

Drawing is an important part of Dutton's practice. She enthusiastically describes three years studying at the Sir Henry Doulton School of Sculpture, which was located close to her studio until its closure in 1993. Dame Elisabeth Frink was patron, and the emphasis placed on life drawing and life modelling set Dutton on a figurative path.

Denise Dutton in her studio

A striking aspect of the sculpture is the spirit and movement conveyed. Anning confidently strides out, chisel in hand and dog at her heels, the sea wind lifting voluminous skirts that cannot have helped her while scrambling over the rocky shoreline. It was a difficult effect to achieve, requiring the welding of a significant armature, layered with hand-knitted wire and what Dutton describes as wooden butterflies to hold the weight of the clay.

'I actually formed her as a naked figure first, because I wanted to get that walk right. I then had to cut back into her to make room for the skirt. I spoke with someone at the V&A and went through the clothing of the time, which was tricky because Mary was not upper class and that is all of the clothing that is really left.

'I turned to a friend, Notty Hornblower, who is an expert in historic clothing. She had some clothing of the era, including some quilted under-petticoats. A local actress called Tilly put the clothing on and we went outside in a breeze. To see the clothing moving as she walked was invaluable.'

The sculpture wouldn't exist without Evie's vision, but both she and Dutton are keen to stress the collective effort that went into the design. 'We worked with the local school children of Lyme Regis to get all their ideas together and to share them with Denise,' says Evie. Ammonites are peppered across the sculpture for children to discover and take rubbings of.

Evie's campaign led to the creation of the Mary Anning statue

'It all came together really well,' says the schoolgirl. 'I think the statue is strong and shows what an amazing person Mary really was. I really like it, and the best bit is Tray. Denise is really good at animals; my mum said not many sculptors can do animals right.' Dutton was helped in this respect by sketches Anning herself had made of Tray. As we sit talking, Dutton's sketches of her own dog, Willow, lie on the workbench next to our cups of tea.

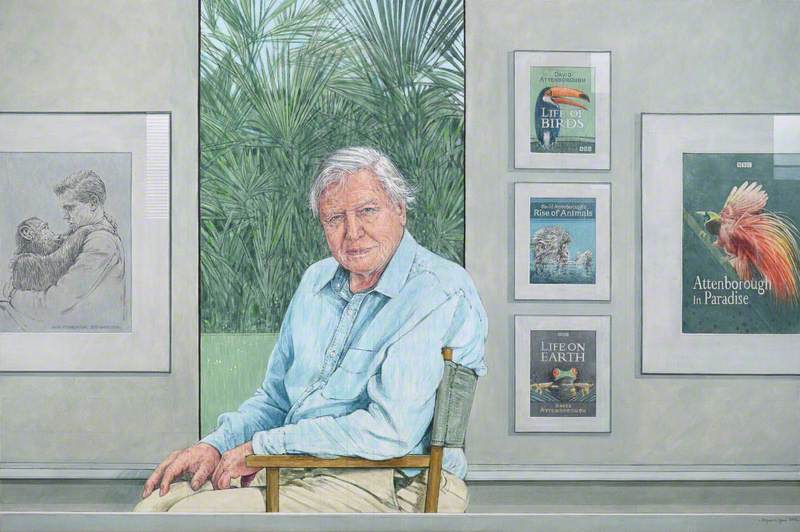

It has taken under four years for the project to come to fruition, which isn't too long considering one of Dutton's commissions, William Cavendish (1748–1811), 5th Duke of Devonshire, spanned 20 years, and the Mary Anning Rocks! campaign has straddled the pandemic. 'Once the initial lockdown rules eased, we would meet up behind a van in the car park at Lyme Regis,' says Dutton, enthusing about working with Evie's mother, Anya Pearson, and the other committee members. Patrons of the campaign include Sir David Attenborough, novelist Tracy Chevalier and Professor Alice Roberts.

Denise Dutton with the maquette of Mary Anning in her studio

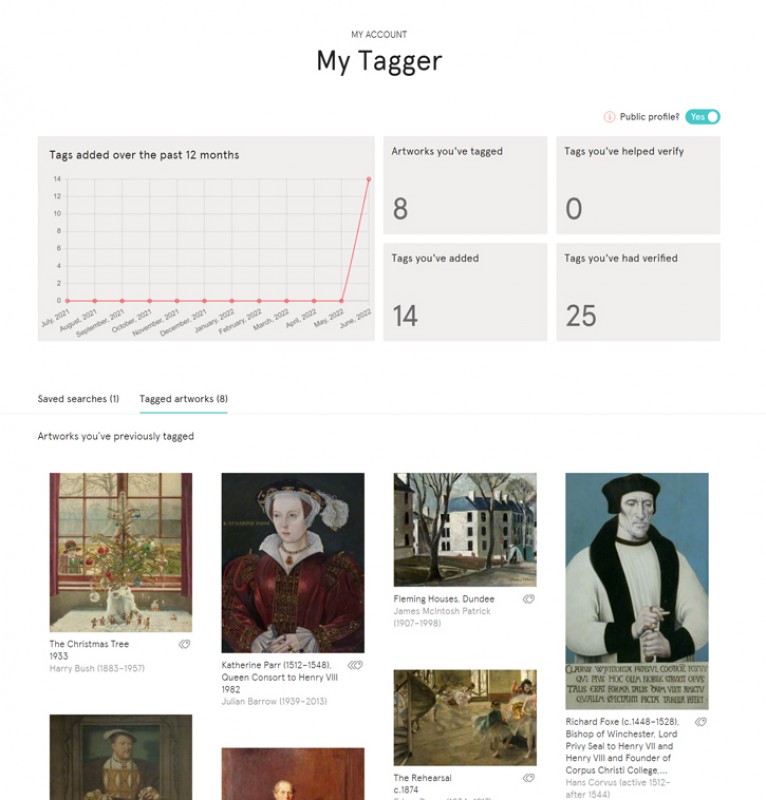

Dutton's process, from initial sketches through to the modelling, silicone moulding, ceramic shell application and casting in bronze, has been documented on the campaign's social media channels. The final work now stands on the Lyme Regis seafront, where the traditional brown bronze will oxidise and slowly turn green.

The campaign has not only demystified the process of public sculpture but, thanks to the tenacity of a 10-year-old girl, revolutionised it.

Gemma Briggs, Head of Marketing and Communications at Art UK

A maquette of the sculpture is on tour at museums across the UK, with visits available on request. Find out more at www.maryanningrocks.co.uk