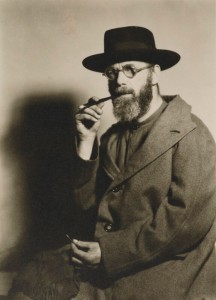

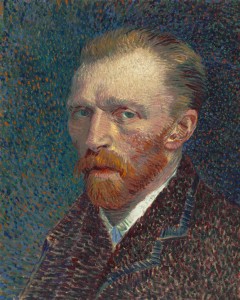

In the far-flung islands of French Polynesia lies the final resting place of one of the world's most revered and controversial Post-Impressionists: Paul Gauguin (1848–1903). Today, over 100 years after his death, his figure still looms large over the islands, with his name used liberally as a drawcard for affluent tourists. There's the 'Paul Gauguin' luxury cruise liner, Paul Gauguin Museum, and even a main street in the capital city named after the man. Replicas of his famous paintings adorn postcards, hang in important government offices and on hotel walls.

For an artist who shunned modernity and all the trappings of capitalism, it is ironic that his work and name are now being paraded as a banner for all the things he detested. However, the most troubling aspect of his posthumous fame in the islands are the myths his paintings continue to perpetuate. These myths centre around European ideas of the 'exotic' and the 'erotic' mixed with Gauguin's own yearning for a 'primitive' lifestyle.

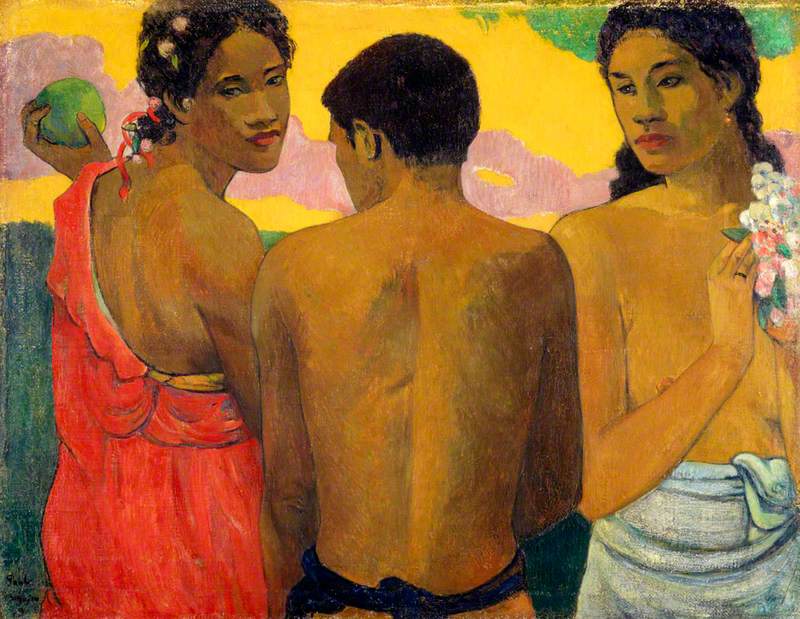

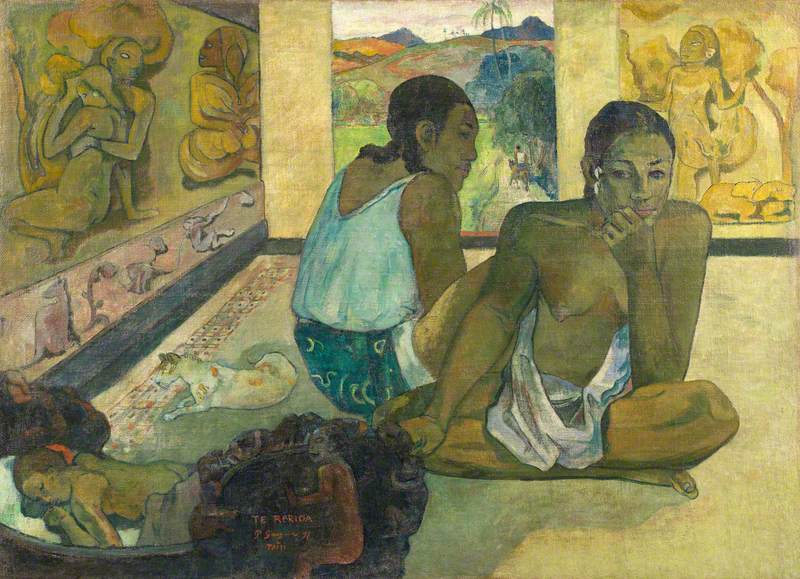

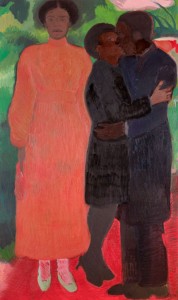

Many of Gauguin's most well-known pieces depict native Tahitian women in various states of dress. What is striking about these works is that the women seem elusive, distant. One wonders what they are thinking and what their side of the story is. The art is intriguing, but it necessarily silences the voices of these indigenous women. What is left is essentially a white, male-centric view of indigeneity. It's important to recognise this when viewing Gauguin's art and appreciate the opportunity we have, as viewers, to seek out and learn about these marginalised women.

Gauguin meets Teha'amana

Gauguin arrived in Tahiti in 1891. He was 43 years old and left behind everything he knew in Europe, including his wife and children. He left seeking a mythical paradise and 'pure' culture on which to base his art. However, Gauguin was disappointed to discover that French colonial influence in the islands had already changed island life. To distance himself from French civilisation and search for the primitive life he dreamed of, Gauguin moved to the district of Mataiea, on the far west side of the island. It was in Mataiea that Gauguin first met his Tahitian muse, Teha'amana.

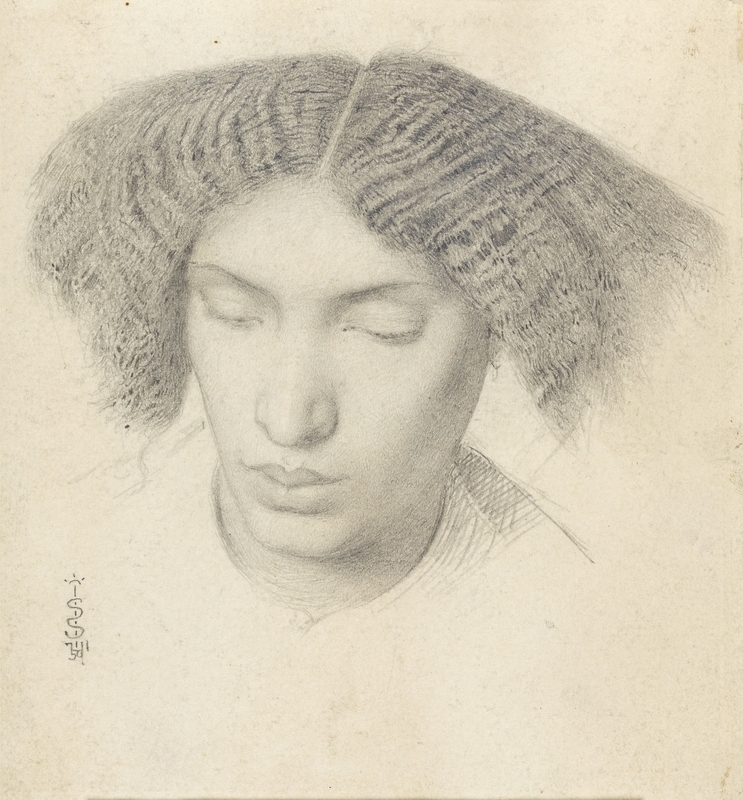

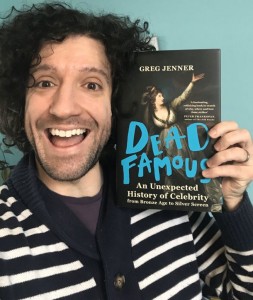

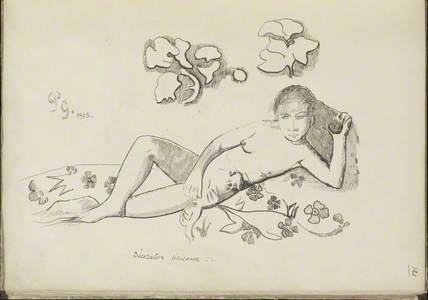

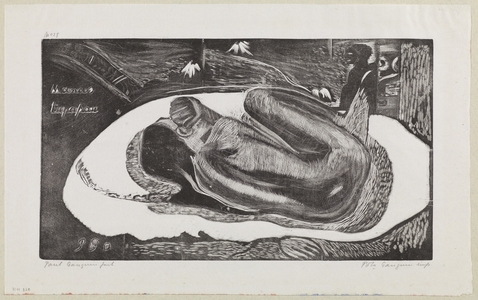

Avant et après

(drawing 'Décorative personne') 1903

Paul Gauguin

Teha'amana, also known as Tehura, was around 13 years old when she met Gauguin, according to Gauguin's own autobiographical journal, Noa Noa. At this young age, Teha'amana quickly became his 'native' wife, although whether she was a willing participant or not is unknown. 'Native' wives were commonly taken by French colonialists like Gauguin at the time, but these marriages were not usually legally binding. Their marriage lasted a few years, until 1893 when Gauguin returned to France. When the artist eventually did come back to the islands several years later, Teha'amana refused to live with him again.

Teha'amana: here's what we know

Much of what we know about Teha'amana today is from Gauguin's own accounts and paintings. It should be noted that it is widely acknowledged that Gauguin fantasised and exaggerated large parts of his own life in his journals and in his art, tailoring them for a European audience.

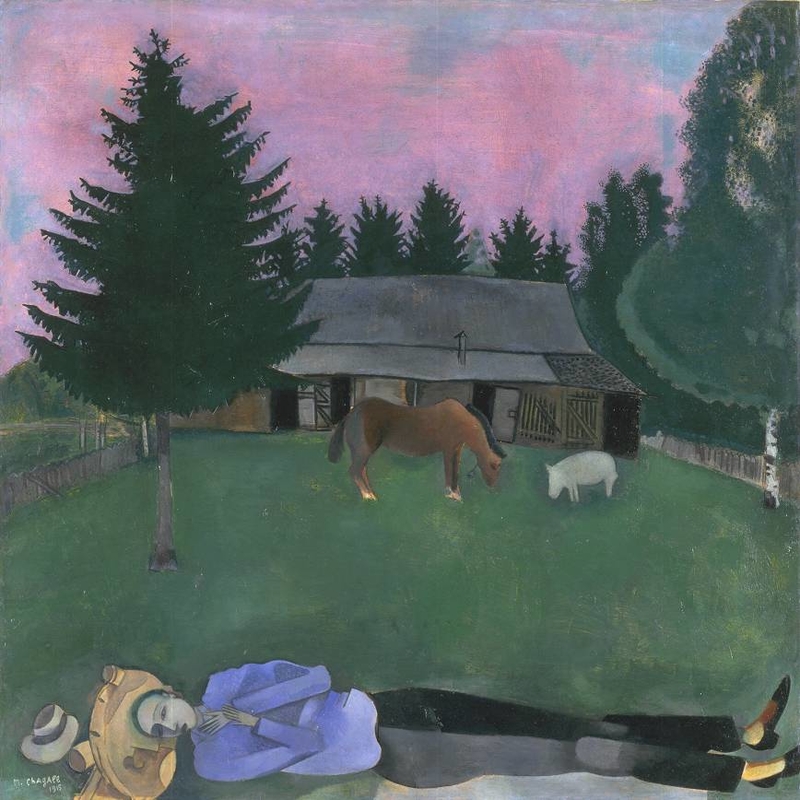

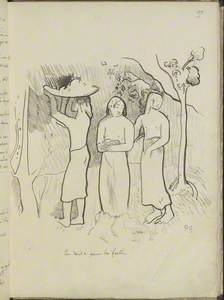

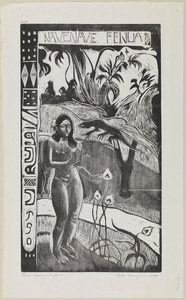

Nave Nave Fenua (Delightful Land)

1893–1894

Paul Gauguin

Teha'amana and her family came to French Polynesia from Rarotonga, in the Cook Islands. She was born on the island of Huahine in the late 1870s before the family relocated to Tahiti. In the world that Teha'amana inhabited, there were three major influences on women: the Christian Church, French colonial rule, and Tahitian culture. She lived during an era when many Tahitians converted to Christianity and embraced its teachings. Teha'amana likely attended church and wore European style clothing regularly. She was subject to French colonial law and probably spoke at least some French as well as Tahitian. She and her family would have lived a subsistence, community-based lifestyle. Tahitians at the time were self-sufficient and able to live abundantly off the land and ocean.

Teha'amana's marriage to Gauguin was apparently arranged and completed in a single afternoon. These marriages were often made by the family to enhance status or financial standing in the community. However, as a foreigner, Gauguin also would have profited immensely in terms of access to fresh, local food and sexual relations. Teha'amana apparently conceived and bore a child to Gauguin during their brief marriage, although little is known about the child who may have been adopted into another family.

After Gauguin's departure to France, Teha'amana remained in Mataiea, married a Tahitian man and had two more children. She died in Mataiea in 1918 from the Spanish flu epidemic. During her life, Teha'amana never came forward to claim any money or fame from being Gauguin's wife, despite his posthumous recognition. Like the other indigenous women Gauguin featured in his artwork and journals, she also never received any of the acclaim that came with it. Nevertheless, the portraits and paintings of Teha'amana are today some of Gauguin's most praised work.

Teha'amana in Gauguin's art

Merahi metua no Tehamana, translated as 'Teha'amana has many parents/ancestors', is a portrait Gauguin painted of his wife.

Teha'amana would have been around 14 years old when the painting was done, although she looks older here. She is wearing a conservative dress and flowers in her hair as though she is ready to go to church and her face bears an enigmatic expression, difficult to read. The pandanus fan is a traditional artefact, still used often in the islands today.

The background of the painting is where Gauguin seems to have taken the most creative licence. Behind Teha'amana's head, we see hieroglyph type characters, which look almost Egyptian. The female figure on the left may be a Tahitian goddess. This background seems to be an effort by Gauguin to emphasise the 'otherness' or 'primitiveness' of Tahitian culture, but the elements have no cultural authenticity.

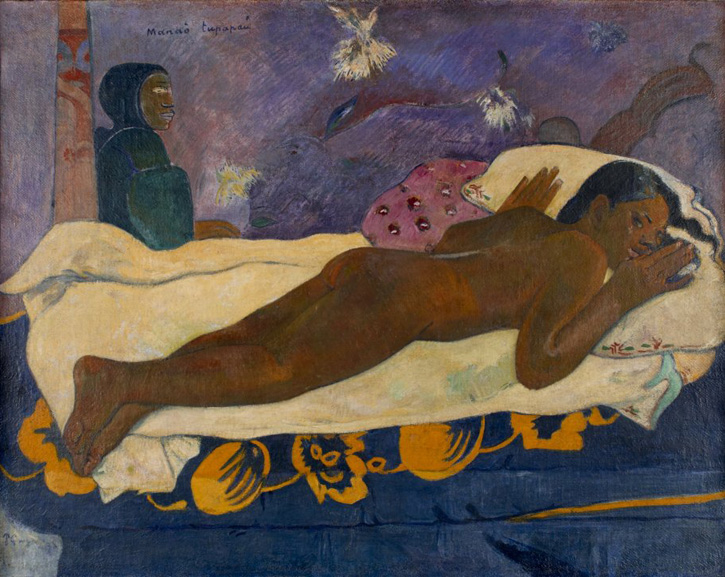

Another Gauguin painting named Spirit of the Dead Watching is one of his most important works. Gauguin himself was proud of this piece and he sent it back to Europe priced at around 1,500 francs – the highest of any piece he sent back.

The main subject of the work is Teha'amana, who is clearly an adolescent in this piece. Her posture looks uncomfortable, and her facial expression looks wary, even afraid. Behind the bed, a woman in profile watches over her – the 'spirit of the dead'. There is something about the composition, colours and figures in this work that is disturbing to look at.

In letters home to his wife, Gauguin described the scene in the painting. He wrote that upon returning home one morning he found Teha'amana naked on the bed staring at him in terror. According to Gauguin, the reason for her fear was her belief that the spirits of the dead roamed the island at night, endangering anyone who lingered outside. This is one possible explanation, although considering that Teha'amana was probably a devout Christian makes it likely that she didn't even believe in these spirits. Another probable explanation is that she feared her own husband and what he would do to her.

While it is impossible to know the true interpretation of the painting, one thing is for sure: it raises questions about important issues such as colonialism, indigenous culture, exploitation, sexuality and spirituality. These questions are uncomfortable but incredibly important. If Teha'amana could speak today, what would she have to say about these paintings?

Tahiti today

In modern-day Tahiti, Paul Gauguin's influence lives on but few people know the name of Teha'amana, his Tahitian wife and muse. However, most tourists visiting the islands have expectations based on myths Gauguin helped perpetuate through his art – whether they realise it or not. Exotic landscapes, enticing women, a submissive culture. It's time that changed. As viewers of art, what can we do? Educating ourselves, seeking out and listening to indigenous communities and celebrating the work of diverse artists is a great place to start.

Tiare Tuuhia, writer