Stanley Spencer's paintings were bought by national collections in the artist's own lifetime. Throughout his career Spencer repeatedly returned to the subject of the 'Resurrection' in paintings that were hugely popular both critically and commercially.

Stanley Spencer was born in 1891 in Cookham, a village that, emotionally at least, he never left throughout his life. The village appears repeatedly in Spencer's paintings: he often used village landmarks as the backdrop to religious scenes and used neighbours and family members as models. Spencer's faith was intense and individual. His father was a church organist, which ensured that, as a child, Spencer was kept in close contact with a religious way of life. Spencer retained his faith his entire life, and channelled it into a large number of his works.

Today the Christian faith remains a seminal aspect of British culture: the myths of Eve and Adam, Mary and Jesus, have blended into the ethical framework of this country until the prohibitions of Moses have become inscribed into the stone foundations of our national soul, as inviolable as habit. But somehow it is this assimilative, unconscious, everyday, even banal level of engagement with religious doctrine that I see in a majority of Spencer's paintings.

Spencer was born at the dawn of the age of irrelevance for the Church of England. There had been Darwin; there was modernism with its plethora of grand narratives aimed at replacing the suddenly shaky national myth of Christianity; and in Spencer's lifetime the two great wars were horrifying bookends to many lives. Church attendance, between the world wars, started to fall, and it hasn't stopped falling. Spencer's art reflects the diminishment of Christianity; its reduction to a kind of background obsession grounded within the banal realities of day-to-day life, even as he obviously delights in the promise of salvation that underlies it all.

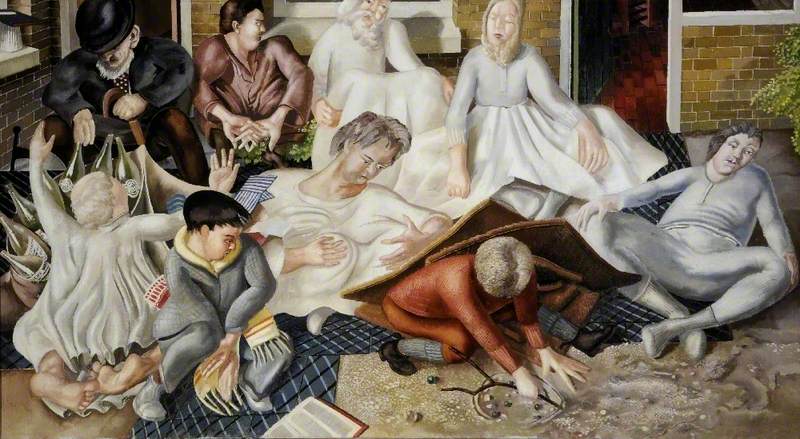

You can see this in his hugely popular scenes of provincial life based in Cookham. In Villagers and Saints (1933) he has children playing with marbles in the street.

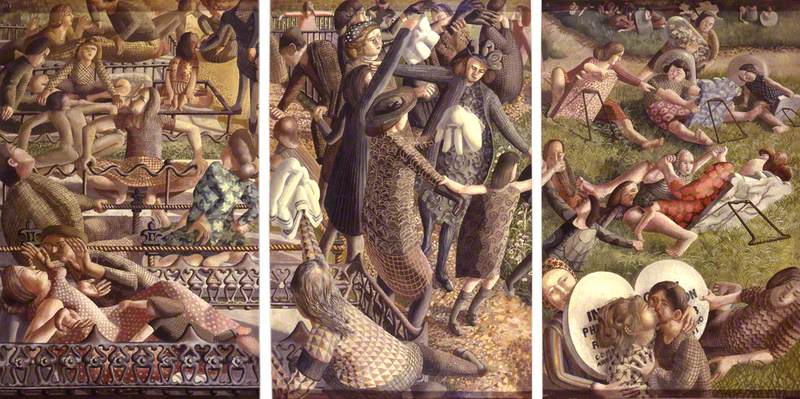

He has an old drunkard sitting on a stoop looking regretfully at his sack of empty bottles. And amongst them, squatting on the pavement in billowing white robes, are a collection of unidentified, mildly bored looking saints, watching over the mortals. Also, in A Village in Heaven (1937) Jesus loiters by the war memorial in Cookham's village square, observing rambunctious villagers courting and playing in a grassy, wooded space (now a tarmacked area crowded with cars).

In his copious notes, collected in the Tate archive, Spencer wrote: 'the instinct of Moses to take his shoes off when he saw the burning bush was very similar to my feelings: I saw many burning bushes in Cookham. I observe the most sacred quality in the most unexpected places.' Spencer's instinct was not to elevate the ordinary so that it lived up to the extraordinary; rather, he literally brought heaven to earth, glorifying in the everyday nature of his lived faith.

However, perhaps because of his first-hand experience of the horrors of war (though such psychologising is speculative at best) Spencer's abiding obsession throughout his life was with 'the happy message of Resurrection'. It is in the large-scale paintings on this theme that some of the desperation of Spencer's war experience, coupled with his profoundly hopeful religiosity is finally expressed.

The first work of Spencer's to gain significant critical acclaim was the gigantic The Resurrection: Cookham (1924–1927), which Spencer exhibited at his first solo show in London in 1927.

In this three metre by five metre painting, acquaintances of Spencer's emerge joyfully from graves in Cookham churchyard to greet each other, watched over by a nude Spencer, a collection of saints, and Jesus enthroned in the doorway to the church. The scene is full of what Spencer described, in an old interview with the BBC, as 'little intimate ordinary personal happenings', such as couples brushing clods of dirt from each other's clothes, or young men reclining on the lids of graves.

In the same interview Spencer grins at the camera, his bust framed against the overwhelming expanse of his painting and says, 'It gave me the feeling that the resurrection was a peaceful occasion and I'm fond of peace and I like the happiness – that was the main idea of this picture.' Spencer's grammatical choice, 'it gave me the feeling' reveals, in my opinion, his conviction of the potency of his paintings. Totemic, powerful: they are the subject of the verb, while Spencer is the object.

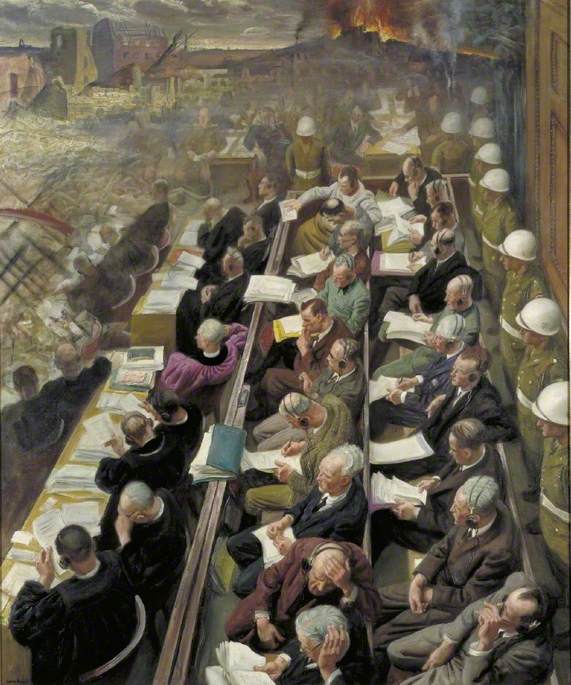

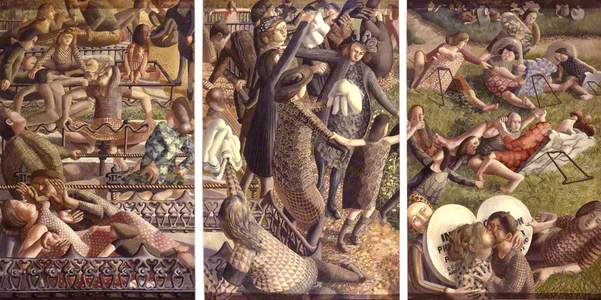

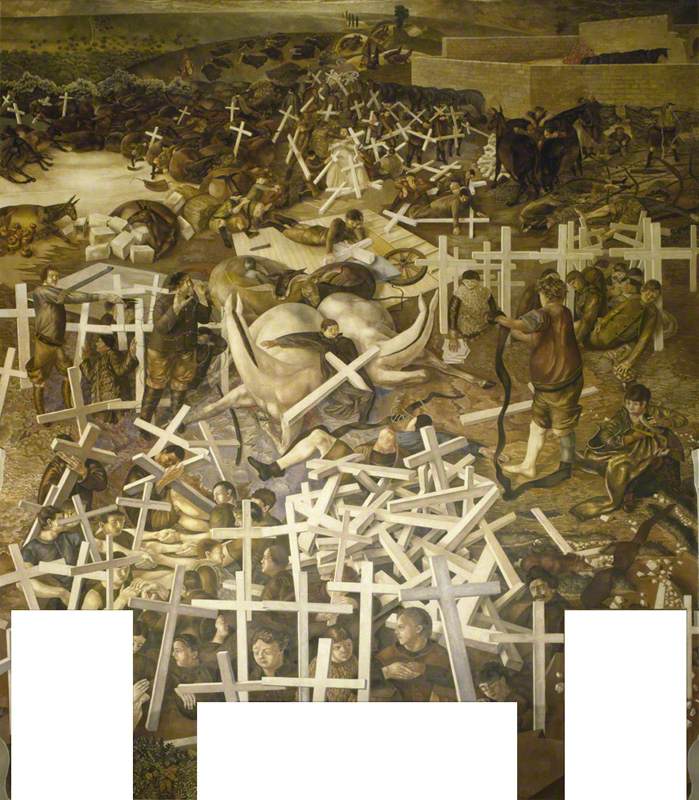

Shortly after this exhibition Spencer began work on a First World War memorial chapel in Sandham. I believe that with this project, Spencer – newly cognizant of the power of his painting – laboured to resurrect the soldiers with whom he had served on the front line. This chapel is full of excellent and fascinating paintings depicting the daily life of soldiers and orderlies during the war, but the crowning achievement is The Resurrection of the Soldiers (1927–1932), which occupies the entire six metre by five metre wall above the altar.

© the estate of Stanley Spencer. All rights reserved, 2014 / Bridgeman Images. Image credit: National Trust Images

The Resurrection of the Soldiers 1927–1932

Stanley Spencer (1891–1959)

National Trust, Sandham Memorial ChapelAt the base of the painting soldiers emerge from the ground and grasp the white crosses that are ubiquitous symbols of the mortal carnage of the First World War. Naturally, guided by the triangular composition of the paintings, one's eye travels up this painting: one observes the soldiers clasping hands in greeting and watches the soldiers walking upwards past revivified horses and handing their crosses to Jesus, who is placed at the apex of the triangle. The success of this painting is in its monumental perspective: it submerges the viewer's consciousness utterly and, for the time you stand in front of it, these men really rise again.

Again, the indefatigably optimistic Spencer appears in archive footage, gazing up at his masterpiece, telling us: 'I felt that all that I hoped for of all the coming back homes and everything would be celebrated there... [the men] are rising in a place in which they would like to rise, it's a happy place, and that I was very keen about, that one makes this battlefield a happy place without altering anything.'

Later in life, after a second stint as a war artist, painting shipbuilders at work on the Clyde, Spencer returned to the theme of Resurrection. He had no specific commission in mind, except for a personal quest to capture a fleeting vision he had had during the war. His vision, he realised, was too vast to fit within one canvas, and so Spencer embarked on several canvases that, though they were bought by various different collectors, he envisaged would be exhibited together.

The two largest of these canvases were The Resurrection: Port Glasgow (1947–1950) and Resurrection: The Hill of Zion (1946). Though these paintings rival his earlier works on this theme for sheer size, I think that they are not as accomplished. Resurrection: The Hill of Zion rehashes the charming, whimsical quality of Spencer's religiously inspired paintings of Cookham that he painted in the twenties and thirties.

© the estate of Stanley Spencer. All rights reserved, 2014 / Bridgeman Images. Image credit: Bridgeman Images

Resurrection: The Hill of Zion 1946

Stanley Spencer (1891–1959)

Harris Museum, Art Gallery & LibraryThere is something absurd about the figures of Jesus and the saints, gathered absentmindedly on a hill overgrown with lilac. Although the composition is admirable, led as it is by the sheer dynamism of the figures' looking, which stages a tug of war between those looking in and those looking out of the motley gang of divinities. Yet the narrative of this painting is uncertain; there is something altogether less celebratory about it, perhaps because the scene is fused out of circumstances that are less desperate than those depicted in The Resurrection of the Soldiers.

Resurrection: Port Glasgow is a more ambitious piece than Hill of Zion, and certainly it is more humorous. Groups of figures structure the scene: on the left a gang of Glaswegians collectively throw the lid from their grave; to the right several figures hold up their hands to heaven in gratitude; and in the middle couples greet each other ecstatically. On the extreme right a gravedigger watches in bemusement as all of his labour is cataclysmically undone.

Though I like this better than Zion, I like it less than Cookham. I suspect this is to do with the limitation of the painting's perspective. The figures largely sit comfortably within the bounds of the painting, politely bending forward so as not to transgress the edge of the canvas. Unlike Cookham there is no great depth: the entire action of the painting takes place within a strictly limited space, and there is no background to speak of.

Whilst in Cookham Spencer captured the delightful sense of the resurrected figures escaping into the horizon, uncontained and uncontainable; in this painting, the great moment of salvation seems a strictly local affair.

Perhaps this localism is forgivable as this painting is one of a series of at least eight, including Resurrection: Re-Union (1945), Resurrection: Tidying (1945), and Resurrection: The Reunion of Families (1945).

Displayed together, this series of paintings could succeed in creating an overwhelming impression of salvation. But, since they never have been exhibited together, it is hard to tell what effect this would have.

© the estate of Stanley Spencer. All rights reserved, 2014 / Bridgeman Images. Image credit: Dundee Art Galleries and Museums Collection (Dundee City Council)

The Resurrection: The Reunion of Families 1945

Stanley Spencer (1891–1959)

Dundee Art Galleries and Museums Collection (Dundee City Council)I would like to see it though. If only because, in his Resurrection paintings, Spencer breaks out of whimsical banality and triumphs in making even a secular viewer to recognise the therapeutic benefit to believing in some kind of salvation.

Victoria Ibbett, Art UK volunteer