Thomas J. Price is having a moment in the UK. He was included in the much talked about group show 'Living Just Enough' at Goodman Gallery on Cork Street and was featured on the cover of Frieze Week Magazine. He has also been awarded the Hackney Windrush Art Commission alongside Veronica Ryan which will be installed in 2021.

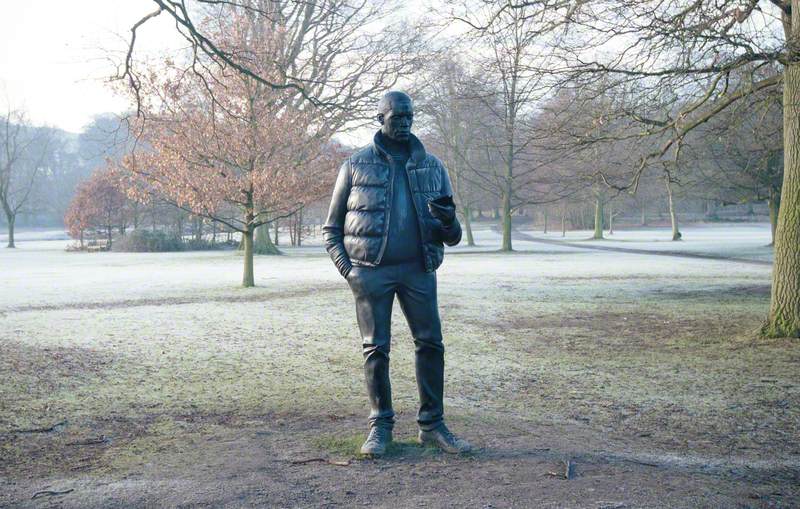

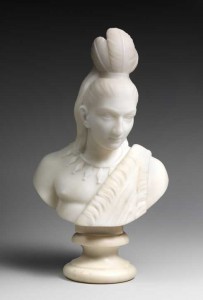

Portrait of Thomas J. Price

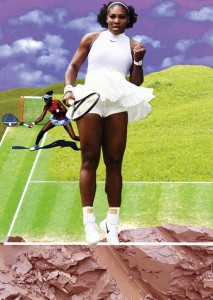

His sculptures of Black men and women looking at their phones or simply standing still, occupying space have real power – both in terms of what they represent, and what they communicate: what kind of art do we typically elevate in public spaces and why?

Price welcomes these accolades, though he feels that his success in the UK has belatedly followed his success in the United States and Canada. In our long conversation, he called for Black British artists to come together and support each other to help promote the rich wealth of artists of colour that we have in this country.

Conversing over Zoom, he opened up about his practice, his latest success and being a Black British artist today.

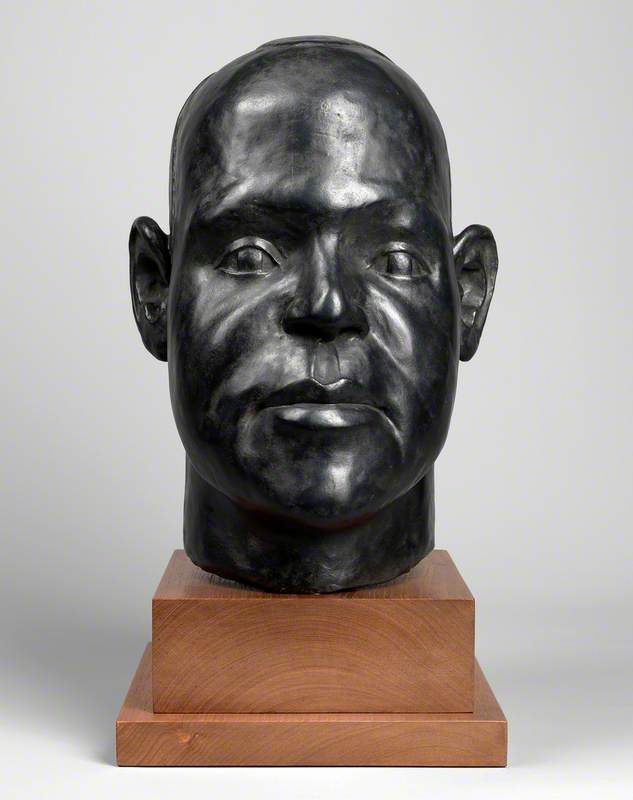

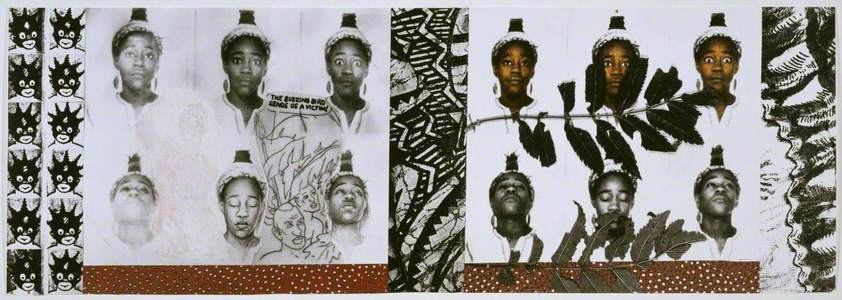

Reaching Out

2020, bronze sculpture by Thomas J. Price (b.1981), The Line, London

Amah-Rose McKnight-Abrams: How are you doing after Frieze Week? I feel like I was hearing your name a lot.

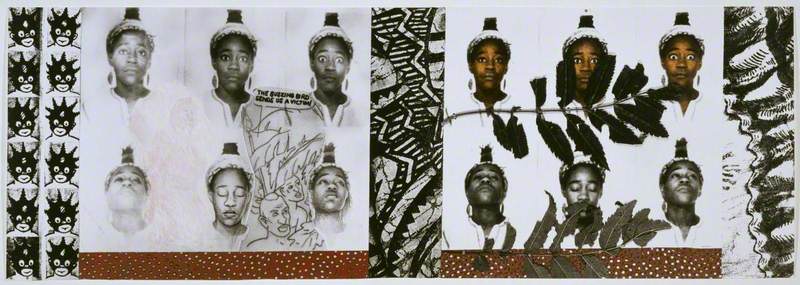

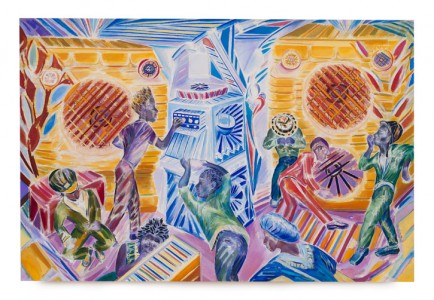

Thomas J. Price: That's really nice to hear. I feel good, I feel good! It was a nice feeling last week, too. Firstly, to be in the show at Goodman Gallery. That kind of line-up of artists was just... Sonia Boyce and Fred Wilson... I remember going in to see Fred Wilson's show at Pace Gallery not that long ago. He's one of the few artists that I refer to when talking about my work. And it's the first time I have shown these works in the UK and so when I saw them holding their own next to Fred Wilson's, I was like, okay!

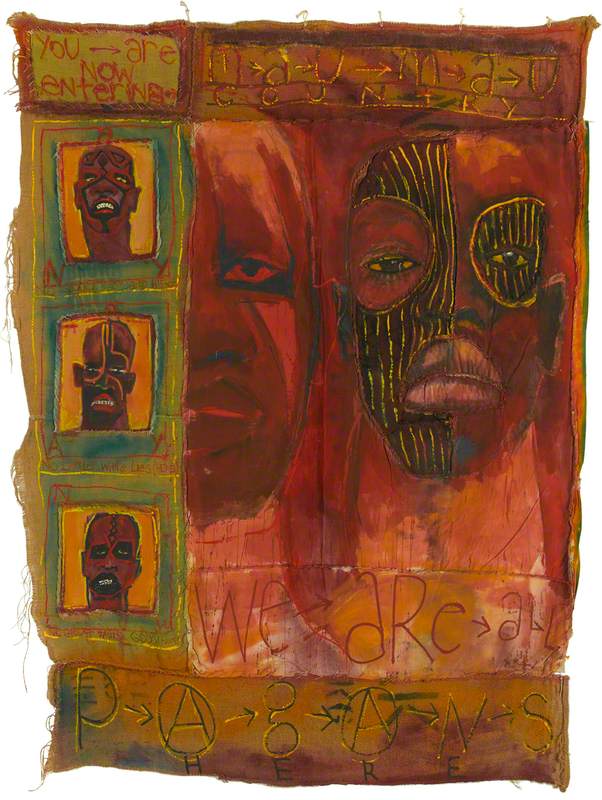

There's just so few avenues to get the ratification from, I think, as a Black British artist in the UK and for a very long time, only a few people properly understood my work. Some people were actively against it, because they either just didn't understand or it wasn't the kind of representation they felt comfortable with. It's like, why are these people not smiling? Why do you only sculpt Black people?

Amah-Rose: It seems strange now, that people would ask you that.

Thomas: It wasn't even them trying to be confrontational, as far as I could work out. It was a genuine de facto stance, or the understanding was that sculptures are 'normally' of white people – typically white men, unless it's nude white women. And so why the hell are you doing this? Why are you not doing that?

Now, obviously, there's a lot more information out there in terms of like representation, but at the beginning, it was a real struggle. I've always considered my work to be very humanist. The first time I sculpted even just a head, it wasn't actually about the race of that head; it was about the fact that I was doing figurative sculpture but that seemed to be controversial in itself. And it was like, 'why are you doing that?'

So, to be one of the names on the cover of Frieze Magazine, and to see how those quite simple, but hopefully quite effective, works were in such a position, with that kind of company, was quite a moment. I haven't really processed everything properly because it gets a bit much, but I suppose it felt like validation of what I've been doing for a long time.

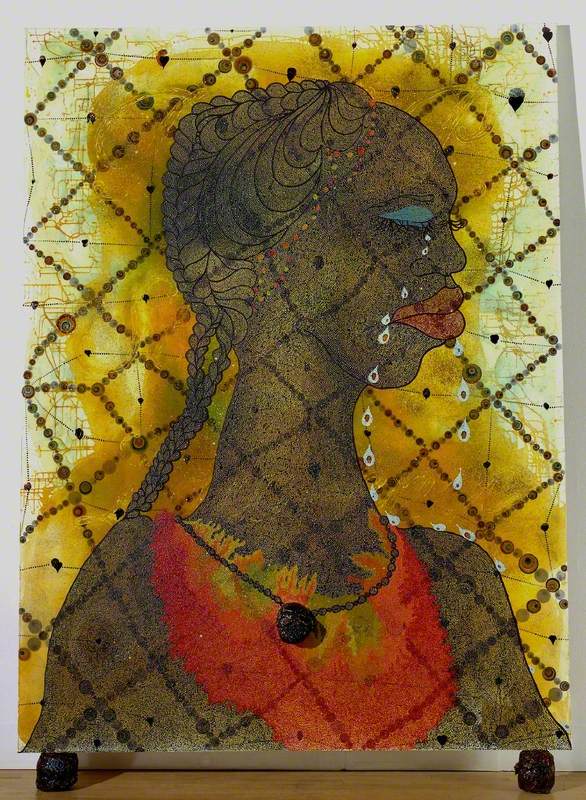

Amah-Rose: I can imagine. What drew you to portraiture? What made you want to make portraits of anybody?

Thomas: I'm interested in the idea of the psychological portrait. All of the individuals represented in my works are fictional – but they're more than fictional. They're not fictional in the sense that they were made up in a narrative sense, but they are propositions in a more kind of a pseudo-scientific sort of experimentation into physiognomy. That includes how their perceived 'race' and how those bits of information impact empathy, how they impact a society's understanding or interpretation of who this individual is, and where do they fit in?

Basically, it's about drawing out the attitudes – the understandings and the learnings of the individual viewing the work. So, by creating this fictional amalgamation of visual information it creates a true, really authentic psychological moment.

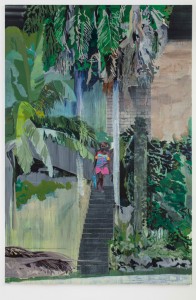

Portraiture, for me, needs to be critiqued and address the question: who normally has their portraits made? My characters are very casual and that is the radical act for me, the refusal to present the 'Black body' in a way that is often demanded by white society.

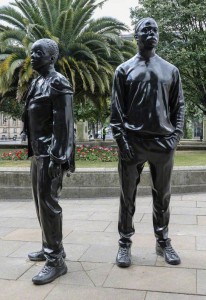

Tasman Road, Figure 2

2008, bronze sculpture by Thomas J. Price (b.1981)

Amah-Rose: Like a winner, a thing of beauty or an object?

Thomas: Exactly and that ties into portraiture itself in terms of, why this person? So yeah, the status of the person portrayed is a very important aspect in my work. The titles of the sculptures of the heads – Head 1, Head 2, Head 3 etc – are about removing the descriptor 'Black'. The amount of times I would hear people describe someone as 'Oh, that Black guy' or 'that Black man'. What is added to a conversation apart from removing that individual from a position of being? When I was at art school, I started to present things as work to be considered by other people, as opposed to just stuff I did in my bedroom, and these were the conversations that I was moving towards.

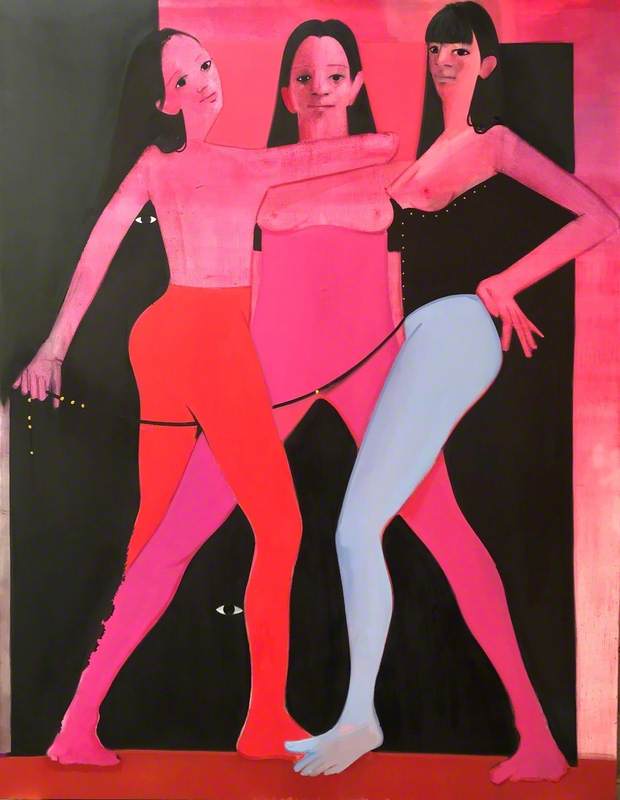

Acrylic Head Series

2005–present, acrylic composite by Thomas J. Price (b.1981), Goodman Gallery, London

Amah-Rose: What was art school like?

Thomas: It was a mixture of things. In one way, it was incredibly exciting and freeing for me because it was an environment where you could experiment with being an artist and project one's ideas and try out different identities. But at the same time, it was totally and unexpectedly the whitest environment I'd ever been into. I went to private secondary school, and that was more mixed than art school. This was something I wasn't prepared for and, looking back at it, was possibly quite isolating and drew my attention more to how we understand one another.

Lay It Down (On The Edge of Beauty)

2018, bronze with automotive spray-paint on wood base by Thomas J. Price (b.1981)

Amah-Rose: Congratulations on the Windrush Commission – how did that feel?

Thomas: I thought, this is an opportunity to actually celebrate and make Black people visible in the UK! Not made by old school, well-intentioned, white sculptors, selecting who they think is important, then presenting them in the way that they think is fitting, even if well-intentioned. I'm making this and I'll be careful... as good or as bad... it's made by me. It will be genuine and made through lived experience to some degree.

I think what is really great about the commission is that it taps into something which I think people have been looking for.

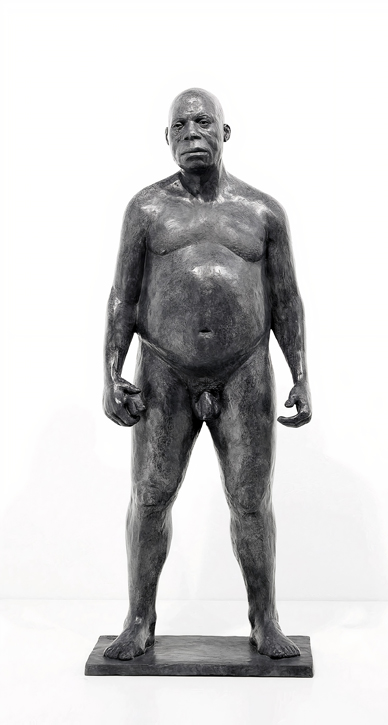

Within the Folds (Dialogue I)

2020, cast silicone bronze sculpture by Thomas J. Price (b.1981)

Amah-Rose: You say you have felt neglected by the institution, but it seems it is engaging with you now.

Thomas: You know what? Then this is new ground for me. I wouldn't say 'neglected', but I do think that for quite some time my work didn't necessarily fit with what they understood art about representation could be. So in a way, yeah. I have no big answer. If this is the beginning of a process, where they talk and listen and take on board what I'm trying to do – then fantastic. All I've ever been trying to do is connect to people. Or talk about my failures to connect to people and question: do you experience the same failure? Yes, race, gender and age can have an impact... so tell me how you feel about what you see?

Amah-Rose: But art is where people find common ground?

Thomas: Exactly, exactly. That's a good name for a show there!

Power Object (Section One, No.1)

2018, aluminium bronze composite with marble base by Thomas J. Price (b.1981)

Amah-Rose: What's coming next?

Thomas: I'm pushing my own things and I feel really invigorated, the work is connecting to earlier ideas that are coming back and being explored again. The figuration seems to be gathering pace, but it's about how to build my fuller practice, to make sure that that is part of the understanding of what I do is really important to me.

If any changes were to happen or any new opportunities come up, it's just about making sure that I know what I'm doing and the direction I want to go in.

Amah-Rose McKnight-Abrams, journalist