The Holburne Museum's first online exhibition, 'Thomas Lawrence: Coming of Age', charts the life and career of Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830) from the age of eleven, when his family first moved to Bath from Devizes, up to the age of 25, when he was elected as a Royal Academician in London.

Of the portraits that he produced during this period, some of his most memorable and perceptive are those that capture the energy, individuality and transformation of the young, whether depicting the fleeting innocence of a child, the determination of an adolescent on the cusp of adulthood, or the ambition of a teenage artist paving a successful career.

Lawrence's own passage into adulthood is recorded in a series of self-portraits, one of the earliest of which was drawn in pastel, a medium which he began working in about a year or so after arriving in Bath in 1780.

Self-Portrait

c.1781–1782, pastel on paper by Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830)

Lawrence and his family had moved to the spa town from the family-owned Black Bear inn in Devizes, where, from as early as the age of seven, Thomas was producing pencil drawings of visitors.

Once in Bath, the reputation of the artist was soon established: at the opening of the 1780–1781 season, Master Lawrence was presented to 'the nobility and gentry' in the pages of the Bath Chronicle. Alongside the press, self-portraits were also an important promotional tool, providing an opportunity to display skills while emphasising Lawrence's youth. His pastel self-portrait strikes this balance between child and artist – his large, childlike eyes are directed towards us as he proudly presents one of his works.

Lawrence rapidly developed his skills as a portraitist during his first couple of years in Bath. Two portrait drawings of his family members, made around the same time as his self-portrait, show his progress.

Miss Anne Lawrence (1766–1835)

1781, graphite on vellum by Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830)

The profile portrait of his 15-year-old sister, Anne, places her in a landscape setting and offers a sense of poise, distance and maturity that differs from the more animated features of Miss Hammond, whose expression combines a sense of amusement and patience while sitting for her cousin.

Miss Maria Hammond, cousin of the artist

1781, graphite on vellum by Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830)

Alongside Lawrence's self-portrait, this portrayal of Miss Hammond is the first to forgo the full profile, and with this change, the sitter's energy and warmth are brought to the fore.

During his teenage years, Lawrence continued to provide a steady income for his family through his pastel or coloured chalk portraits of Bath's population. Less common are his portraits in pencil from this period, rare examples of which include the aforementioned drawings of his sister and cousin, as well as his studies of brothers Abel and Samuel Dottin, who had recently inherited their father's wealth including a plantation in Barbados called Grenada Hall.

Abel Rous Dottin (1768–1852)

c.1784

Thomas Lawrence

Though born only two or three years apart, there is a noticeable age difference between the elder brother, Abel, who appears on the brink of adulthood, while his younger brother Samuel still carries the boyish features of a young teenager.

Samuel Dottin (1770–1797)

c.1784

Thomas Lawrence

When Lawrence drew these portraits he would have been between the ages of the brothers and therefore making his own transition from child to adult. Nevertheless, the artist's extraordinary ability to capture the likeness and psychology of each sitter is already discernible.

By the time Lawrence turned 18 he was ready to embark on a new chapter of his career in London. The teenage artist moved with his father to the capital in 1787, which had all the opportunities for training and publicity he needed to continue building his reputation and network.

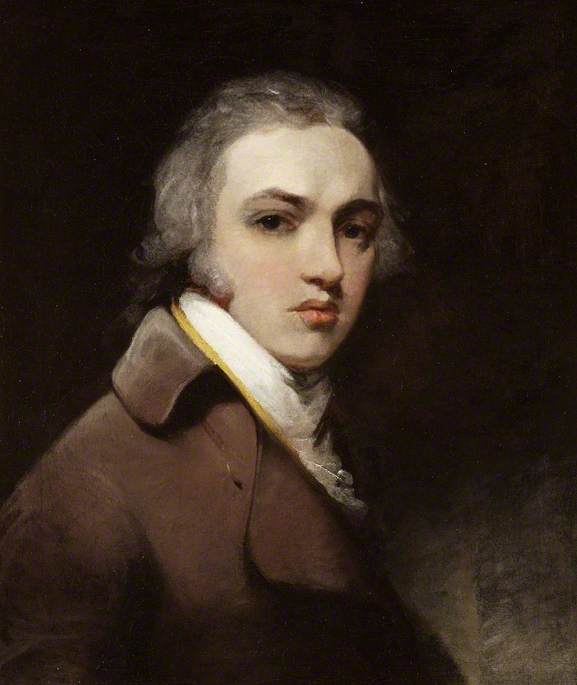

Self Portrait

c.1787, oil on canvas by Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830)

He introduced London audiences to his work with a self-portrait, one of the first to be painted in oil. Though legally still a minor, Lawrence constructs an image of himself as a gentleman and professional, no longer a child prodigy to be remarked upon for his youth. As is evident from this self-portrait, this period of transition from Bath to London, pencil and pastel to oil, and childhood to maturity is marked by a stylistic change that combines an atmospheric use of light and shade with fluent, expressive brushstrokes that bring to life the various textures.

Having produced portraits of several young sitters in Bath, by the time the artist had arrived in London he had already learnt that children, with their mobile features and restless bodies, present particular challenges when it comes to capturing a likeness. Not least was the issue of keeping a child occupied and at ease during sittings lasting up to three hours. According to one of Lawrence's early biographers, the first of these sessions would be spent drawing the sitter's likeness directly onto the canvas. At the following session, he would start painting the sitter's head.

Unfinished Portrait of a Young Girl

c.1790, oil on canvas by Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830)

This technique is evident in a portrait of an unknown girl from around 1790. The child's face is almost finished, the painting having probably reached the third or fourth sitting (Lawrence generally required eight or nine for a complete canvas), while her form and clothing begin to emerge from Lawrence's fluid lines and feathery brushstrokes.

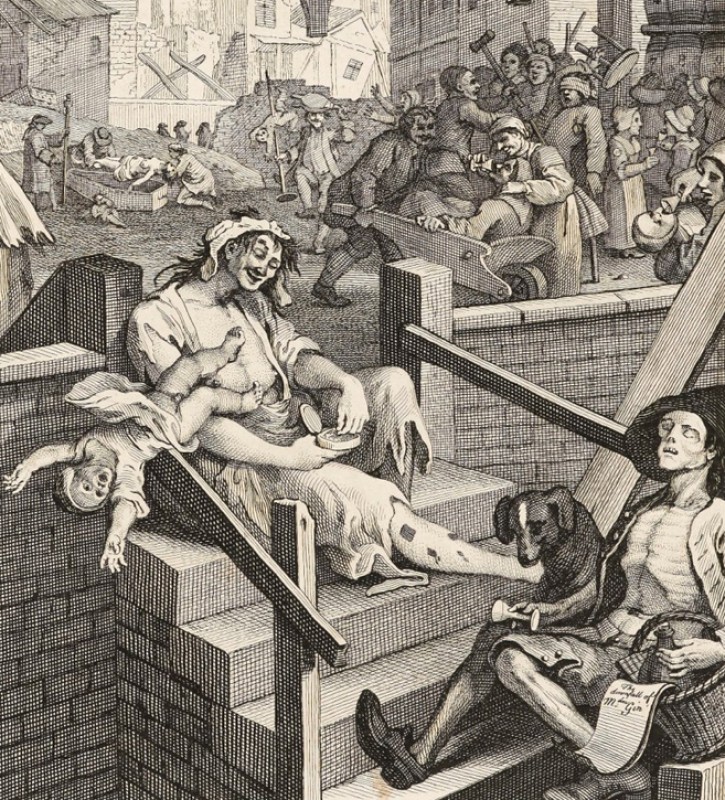

This was a period in which child portraiture had become established as a genre in its own right. Following in the footsteps of William Hogarth and Thomas Gainsborough, Lawrence was part of the second generation of artists who met the growing demands from patrons and parents to produce works that capture the fleeting youth of their offspring. The emphasis in these works was not so much in dynastic succession as had previously been the case, but rather in expressing something of the nature of growing up and the individual personalities of each child.

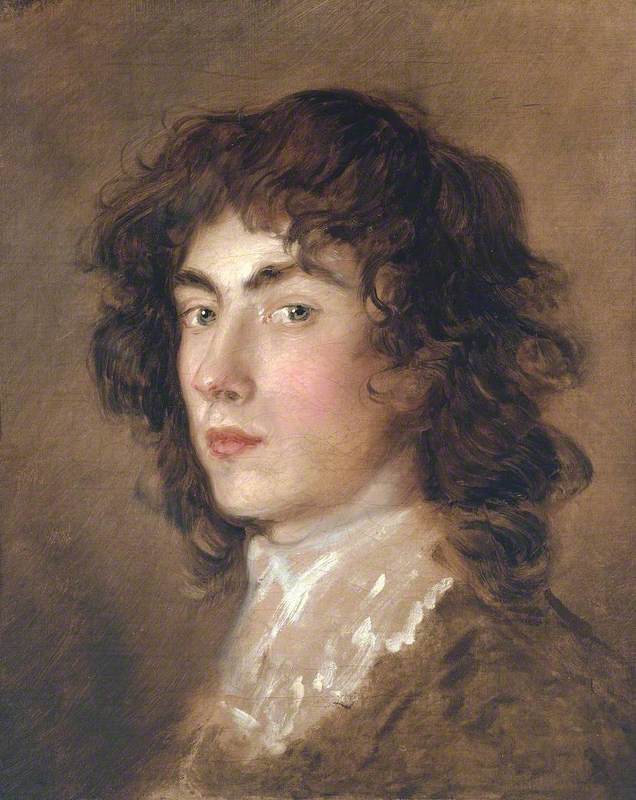

The youngest of privileged families (and therefore the least important in the hierarchy of inheritance) also had their portraits painted, such as William Linley, the youngest of twelve children in a famous Bath family of musicians, whose likeness Lawrence captured in a work now in Dulwich Picture Gallery.

This portrait was made sometime between Linley leaving school at 16 and his departure for civil service in the East India Company when he was 20. He is presented as neither fully a child nor adult: he retains the smooth fringe of a schoolboy (when George III saw this portrait he commented 'Ah! Ah! Why doesn't the blockhead have his hair cut?'), while the three-quarter profile suggests that his attention is focused, not on his present surroundings, but rather to the future that lies beyond the canvas.

Unfinished Portrait of Arthur Atherley (1772–1844)

1791

Thomas Lawrence

Around two years later Lawrence embarked on a portrait of another school-leaver, Arthur Atherley, who was graduating from Eton College. The unfinished work in The Holburne Museum's collection is one of two versions, the other being a quarter-length portrait that was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1792 and is now at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Compared to the larger work, the focus on Atherley's head in the Holburne painting draws attention to his stern expression and penetrating gaze, a look that suggests a wish to be taken seriously. The difference between the two eyes, however, one concealed by the shadow while the other shines brightly, communicates a mind caught between anxiety and confidence, childhood and maturity.

After seven years of building his reputation in London, at the age of 25 Thomas Lawrence was elected as a Royal Academician. His Diploma work took the format of a half-length portrait and presented an imaginary subject titled A Gipsy Girl.

The work depicts a young woman who, bare-chested and on the cusp of adulthood, has seemingly lost her innocence. Holding a stolen chicken, the girl confronts us with a direct gaze that can be read as either a gesture of adolescent defiance or as an appeal for compassion as she endeavours to feed a suffering rural family. In its ambiguity, energy and emotive qualities, Lawrence's Diploma work is a tour-de-force in expressing the complexities of youth.

Sylvie Broussine, Assistant Curator at The Holburne Museum

'Thomas Lawrence: Coming of Age' is at The Holburne Museum in Bath until 31st May 2022