I remember all too well the fatal moment I discovered the painter David Tindle. In Abbott & Holder, a picture dealers in Bloomsbury, I stared at one of his landscapes – sand, mud, a bruised horizon – and was overcome by a covetousness so powerful it felt unnervingly like lust.

Luckily, it isn’t necessary to be in possession of large sums of cash to spend time with his work. Tindle, a wonderful painter whose sensibility, so contemplative and tender, places him in a line of artists that can be traced back to Samuel Palmer and forward to George Shaw, is well-represented in our museums and galleries.

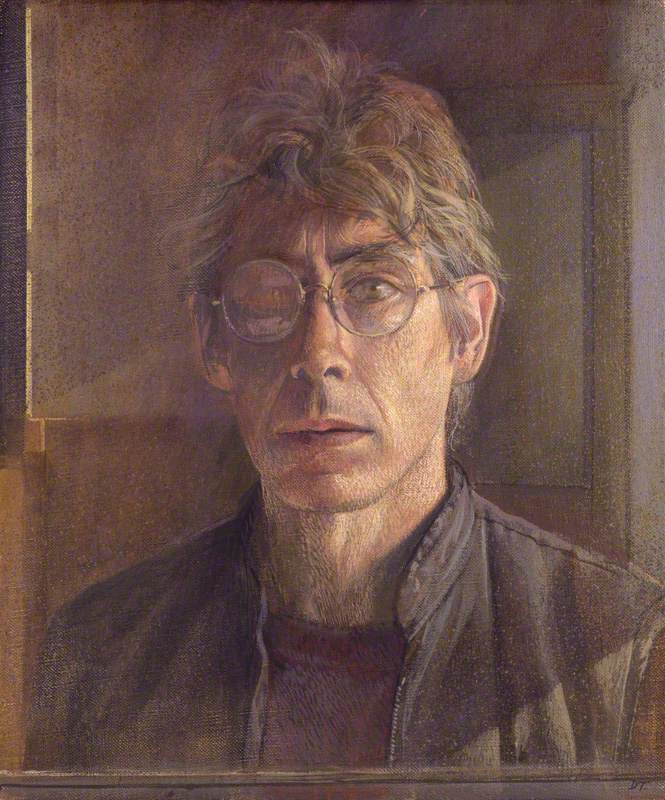

A retrospective of his career – which continues still, in Tuscany, where he has lived and worked for the past two decades – can also currently be seen in Huddersfield, the town where he was born in 1932. Yes, he is sorely neglected, something I regard as both an unfathomable mystery and a terrible slight. But there is one upside to this: on a sunny day, and perhaps even on a rainy one, you are likely, in any given museum, to have his canvasses all to yourself.

Tindle’s start in art wasn’t particularly auspicious. His formal education consisted of six months at junior art school in Coventry, after which, at the age of 14, he found work in a local commercial studio. Two years later, he was taken on as an assistant by Edward Delaney, a London-based theatrical scene painter – an experience that was to have a lasting influence – and it was therefore in the capital that, at 19, he had his first show.

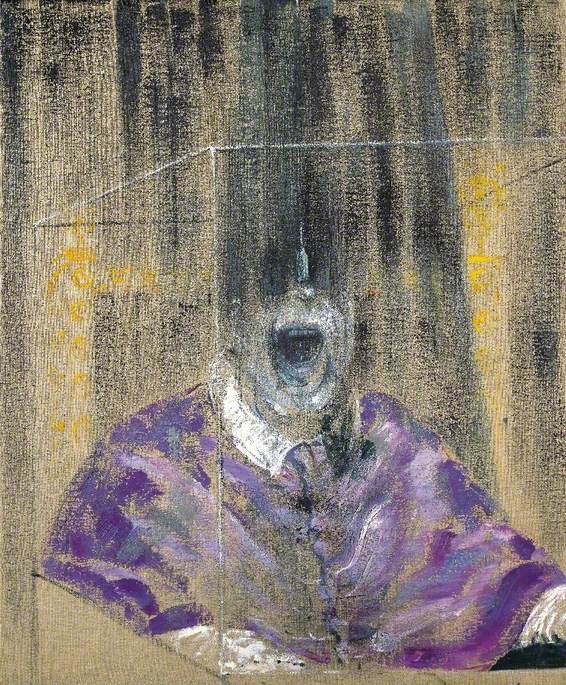

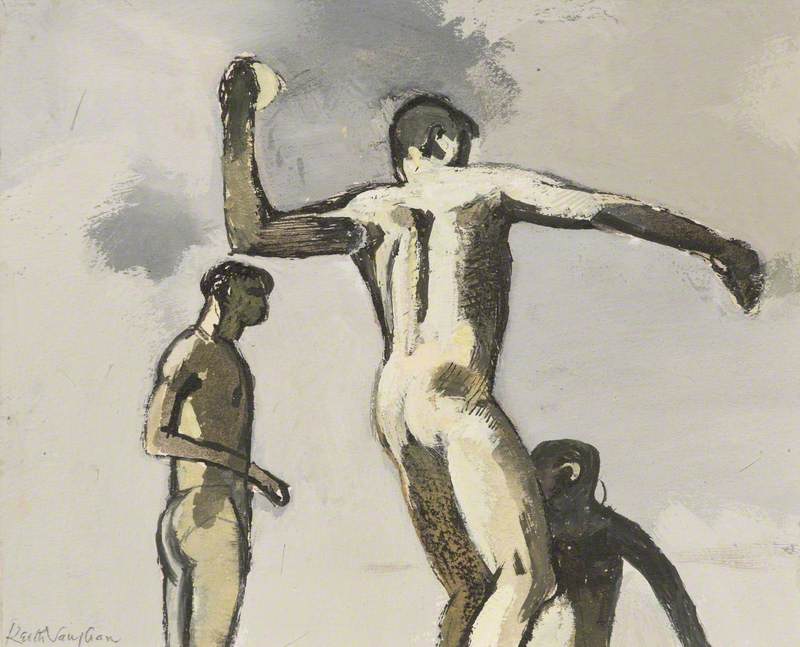

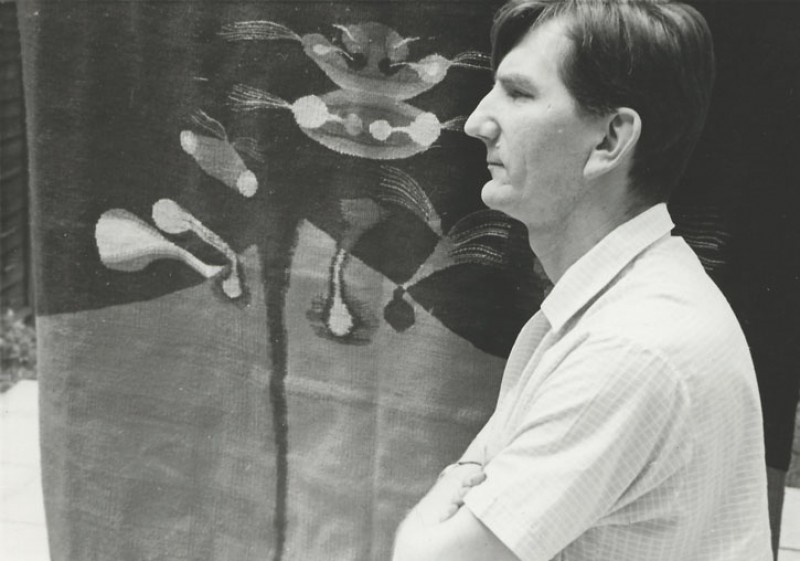

An admirer of John Minton, Tindle found his number in the telephone book and rang to invite him to see it. The two became friends, and Minton introduced him to his circle, whose number included Francis Bacon, Keith Vaughan and John Craxton.

Older and established, meeting them boosted his confidence: ‘I stepped out of my own direct contemporaries, and learned to live, and to think, in a more adult way, about painting,’ he recalled in a conversation with Ian Massey, the curator of Huddersfield Art Gallery’s retrospective.

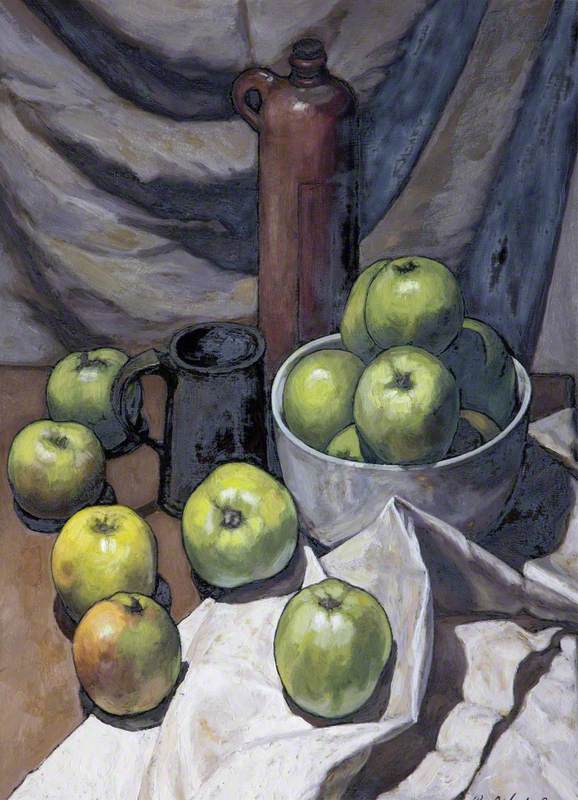

Teasel Plant, 21 Warwick Crescent, W2, London

1955

David Tindle (b.1932)

Ambitious to develop as an artist, he was, at the beginning of his career, ‘very susceptible to influence’. Govette (1955) and Teasel Plant, 21 Warwick Crescent, W2, London (1955) bring early Lucian Freud immediately to mind, while his smudgy landscapes of the 1950s and 1960s – among them Beach 61' (1961) and Vere Street (1961) – are reminiscent of Frank Auerbach’s work from the same period.

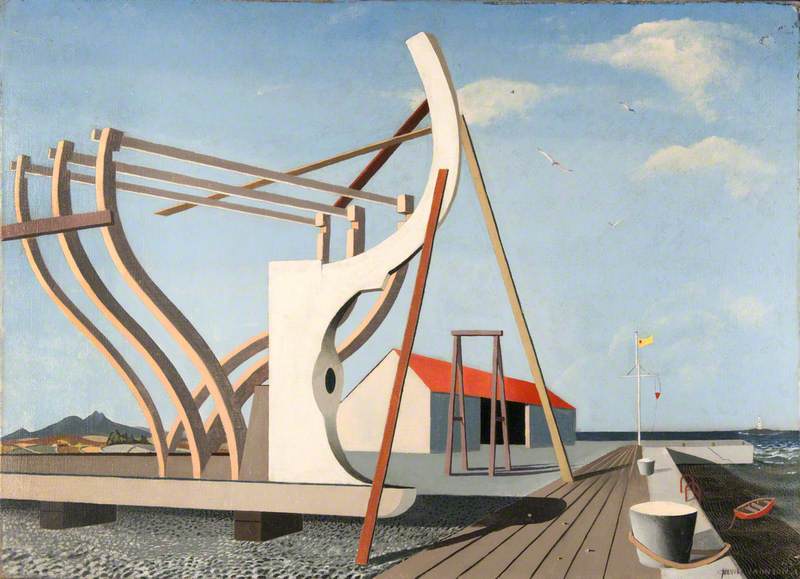

Minton’s influence is apparent in paintings such as Fishing Nets (1957) and Fishermen and Boat, Arbroath (1957), while that of Prunella Clough, another painter he admired, can clearly be seen in Shell Site, South Bank, London.

Shell Site, South Bank, London

David Tindle (b.1932)

Nevertheless, Tindle brings something that is all his own to these canvasses: an eerie stillness which may be felt almost as a presence. His still lifes of the late 1960s and early 1970s are transcendent, numinous, the objects arranged in them, whether on a mantel or table, as if on an altar.

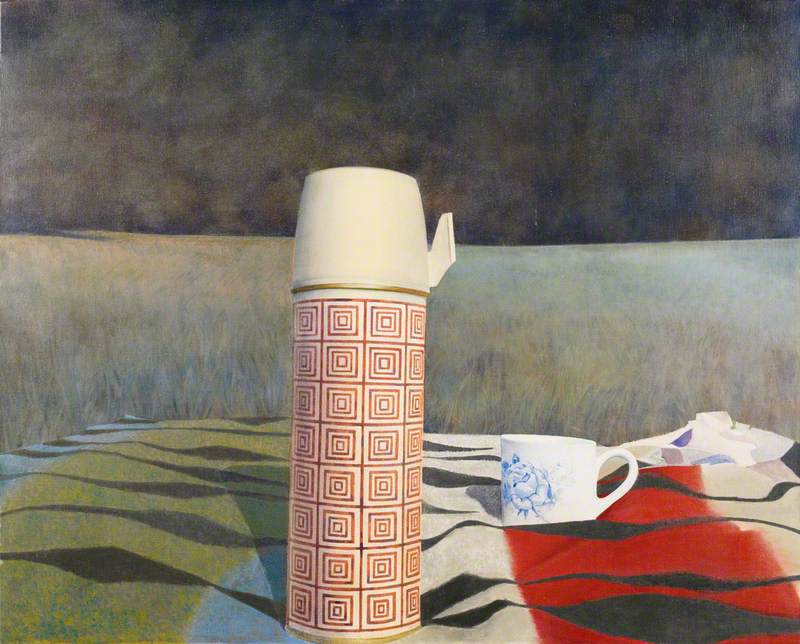

Tea (1970–1971) is a painting of thermos flask and a tea cup on a picnic rug: such ordinary, commonplace things. But look closer. Beyond the flask, the field looms up almost monstrously to meet a blue-black sky. Once you’ve noticed this, the whole thing suddenly tilts, shifting on some invisible axis, the thermos taking on an altogether different quality. How noble it now seems, like a lighthouse in a storm.

This sense of a creeping darkness is developed more fully in Tindle’s mature work, produced after he began painting in egg tempera, an exacting medium he adopted in the early 1970s, and which helped him to achieve a ‘crisper articulation of form’.

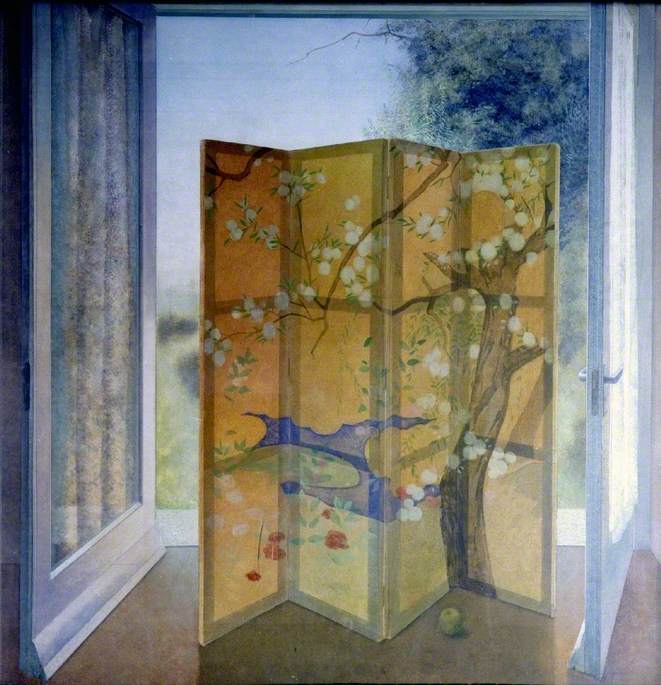

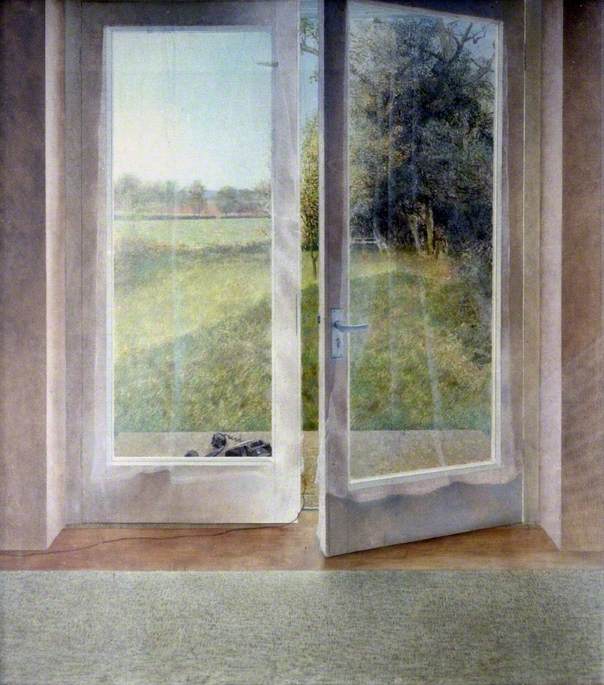

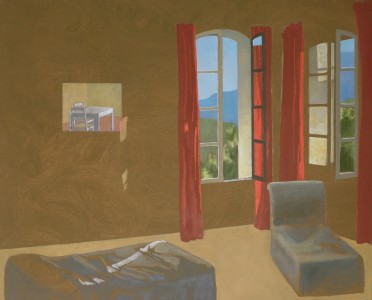

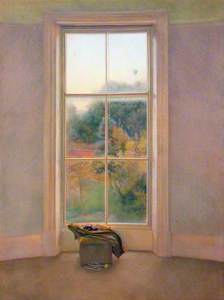

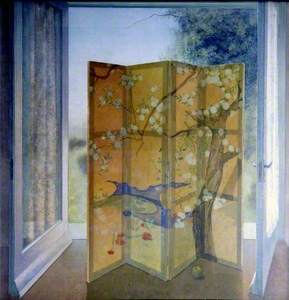

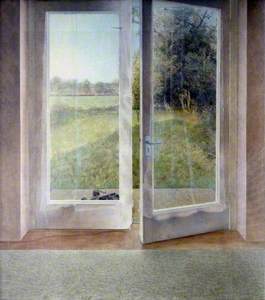

The most perfect expression of this painterly veracity – a quality that plays, in the most delicate and subtle of ways, with the idea of realism – is to be found in the series of gardens (I’ve referred to them elsewhere as ‘verdant rooms’) that he made his primary subject in the late 1970s and beyond: among them Door Slightly Open (1978), Mural (1978, reproduced at the top of this article), and The Garden (1977).

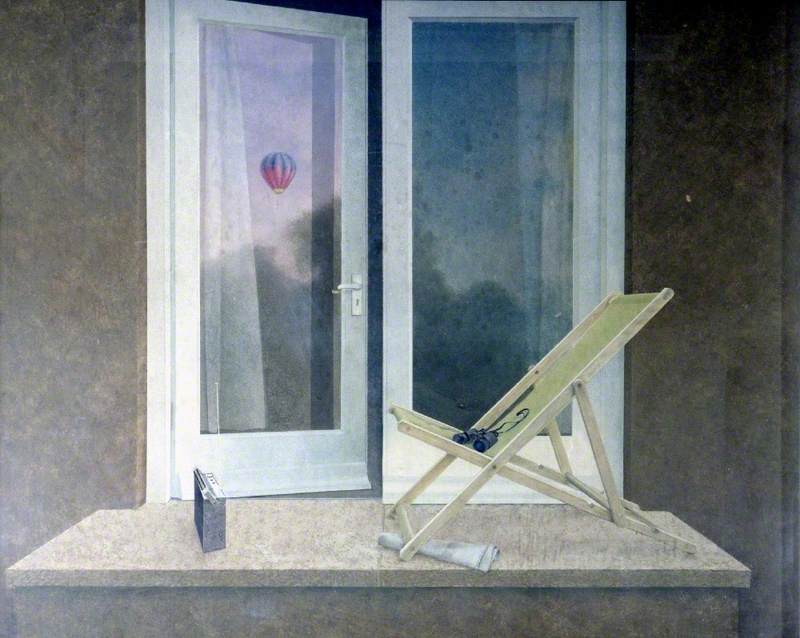

At first sight, these extremely skillful paintings, with their recurring motifs of doors and windows, seem so tranquil and English. There is a kind of perfection in the way he balances the light with all that greenery, the one setting off the other. But if a deck chair happens to be in the picture, it will be always empty, and if a door appears, it will very often be ajar; a curtain might blow in a breeze. People, you sense, have recently departed these places, slipping out unseen, and for this reason, they feel spectral, inhabited by ghosts.

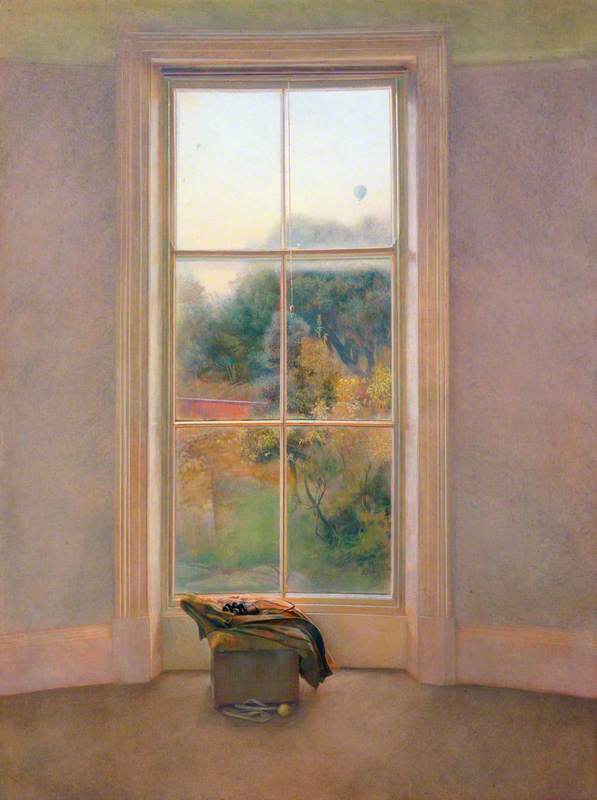

Balloon Race, Clipston (1980–1981) is, it seems to me, a narrative masterpiece, its outward simplicity – here are objects piled by a window, from which can be seen autumnal trees and a distant hot air balloon in the late afternoon sky – being so entirely at odds with what it stirs up in the viewer. Its every element speaks of departure, of leave-taking. For all its considerable beauty, it is so melancholy, a moment at once universal and yet already lost. Here, then, is Tindle’s great and universal theme: time, and its passing. How it gnaws at our human hearts.

Rachel Cooke, journalist and writer