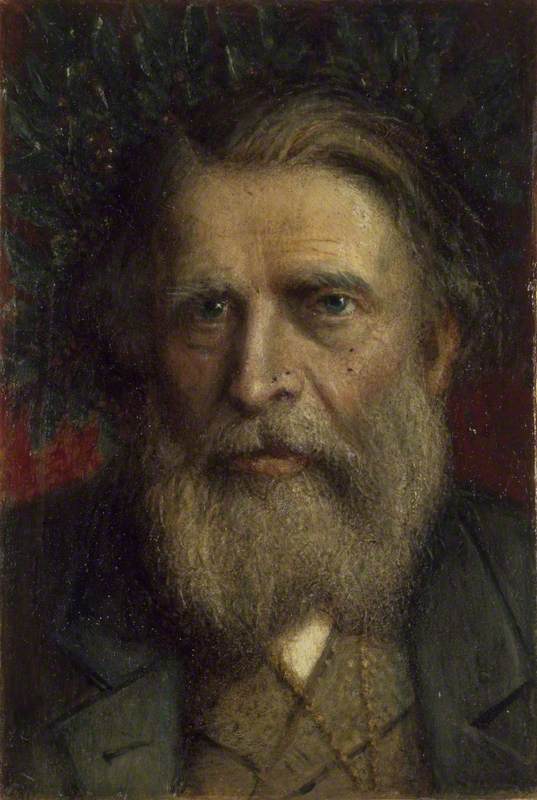

For John Ruskin (1819–1900), fine art is created when ‘the hand, the head and the heart’ work well together. This spring museums and galleries across the UK are celebrating Ruskin’s 200th birthday. A wealth of exhibitions, lectures and workshops will bring his visionary criticism and joyful watercolours to fresh audiences. From his close encounters with Turner’s

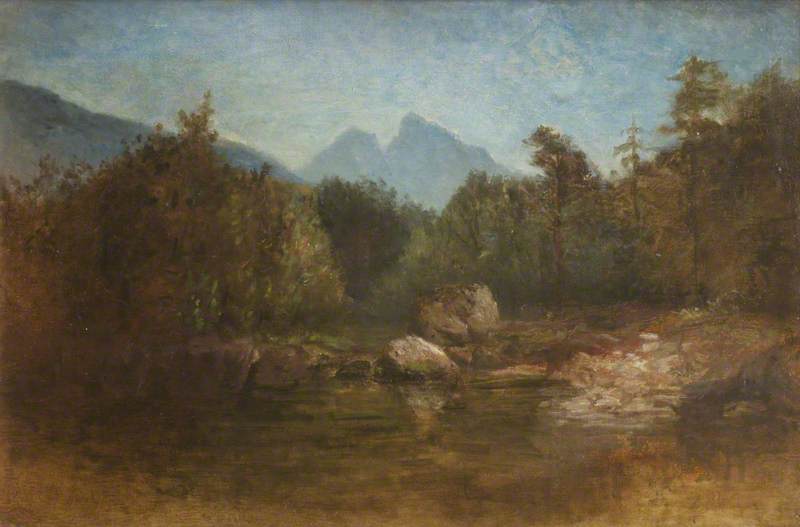

Ruskin knew that looking can make us ask how something is made. Or who made it? Or why? Seeing the ground beneath our feet or the sky above helps us to feel part of an intricate network of living things – what Ruskin would call Creation. And it was not just the plants and animals that drew his attention. For him, the flow of water through a landscape, the channels cut by a stream and even the rocks of the stream bed were filled with possibilities for beauty and storytelling. His first love was geology, and he was always searching for the deep history of river valleys, the movements of glaciers or the upswelling of mountains.

This desire to look closely at the workings of nature began early, as he describes in his autobiography. His Scottish aunt ‘had a garden full of gooseberry-bushes’ that sloped ‘down to the Tay, with a door opening to the water, which ran past it clear-brown over the pebbles three or four feet deep; an infinite thing for a child to look down into’. The constant swift motion, the tumbling stones, above all the sense of freedom, combined to make this long-looking a greater delight. And he takes us with

Throughout his life, Ruskin loved the movement of water. As an old man, he built cascades behind his house at Brantwood, and as a young man, he could happily spend ‘four or five hours every day in simply staring and wondering at the sea – an occupation which never failed me till I was forty.’ And so he began to understand how water changed everything it touched, from the green edges of a river bank to the rigging of a boat. He noticed things that other people missed. This made him an extraordinarily perceptive art critic.

He was also a generous mentor, encouraging young artists, like John Everett Millais and Elizabeth Siddal. He championed the intimate paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites, who seemed to fulfil his desire that ‘Nothing must come between Nature and the artist’s sight; nothing between God and the artist’s soul’. He donated many of his beloved Turner drawings and watercolours to museums around the country so that students and working people could have access to the best examples of British art. He promoted lifelong learning. He helped young men and women to discover their own talents for drawing, with his step-by-step guide.

Ruskin began his Elements of Drawing by stepping outside: ‘I would rather teach drawing that my pupils may learn to love Nature,’ he explained, ‘than teach the looking at Nature that they may learn to draw’. He gives us the tools to ‘to set down clearly, and usefully, records of such things as cannot be described in words’. And he shows us how to ‘preserve something like a true image of beautiful things that pass away, or which you must yourself leave.'

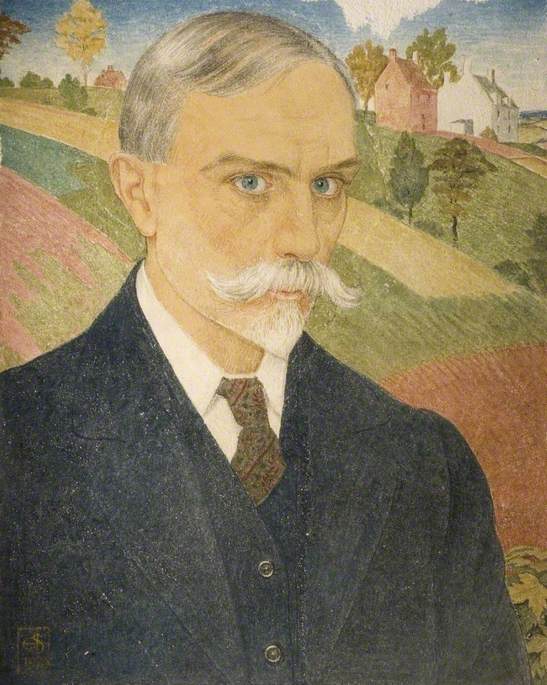

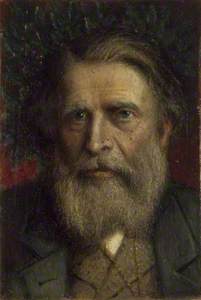

Study for the Head of Mary Magdalene in 'The Morning of the Resurrection'

Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898)

So over the coming months, as we celebrate Ruskin’s writings and paintings, he will again help us to see new and wonderful details in the world around us. He can guide through grand pictures by Turner or Burne-Jones, unravelling their myths and complexities. Or he can stand beside us as we enjoy the small pleasures of a leaf, a petal, a pebble. As he said, ‘To see clearly is poetry, prophecy, religion – all in one.’

Suzanne Fagence Cooper, art historian and author of To See Clearly: Why Ruskin Matters, published by Quercus Books on 21st February 2019