The Victorian painter Thomas Stuart Smith is possibly best known today for founding and giving his name to The Stirling Smith Art Gallery & Museum.

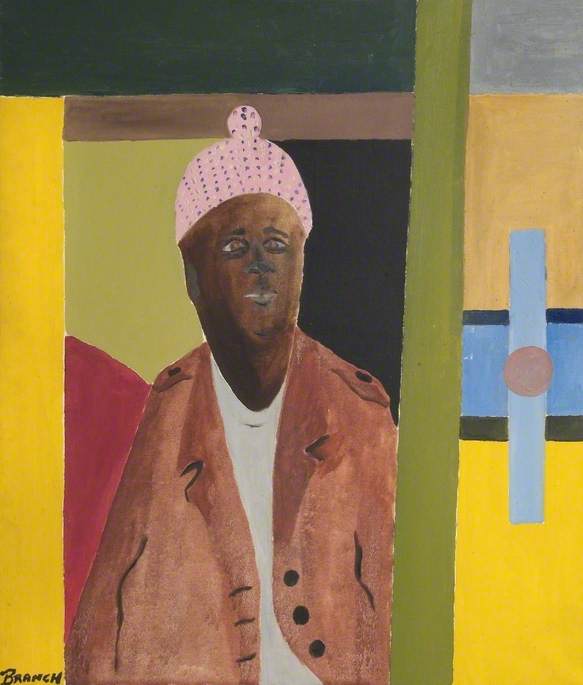

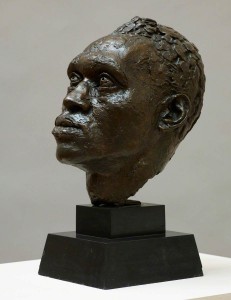

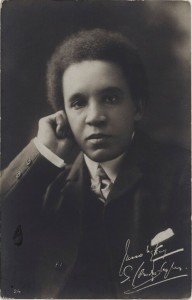

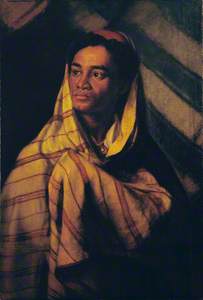

Two of Smith's works are still among the most important works in the museum's collection. They are portraits of black men painted at a time when it was rare to see depictions of people of colour other than as servants.

The first painting was entered for the Royal Academy exhibition in London in 1869, where it was accepted, but was hung in an

The painting has been extended at the bottom to fit the fashion of the time and possibly to give it more chance to get into the RA exhibition – Smith thought that square paintings were not as popular as portraits.

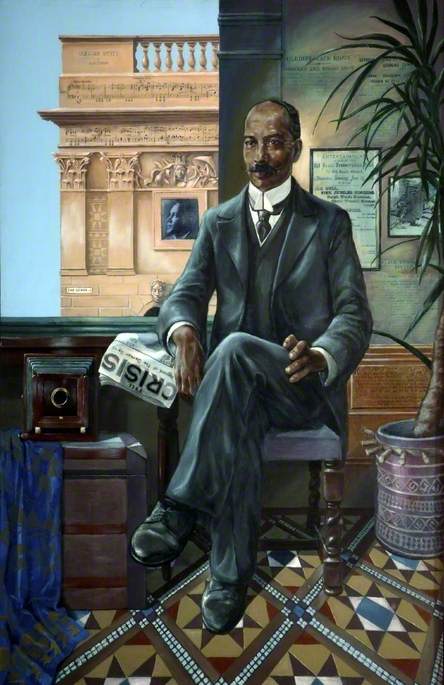

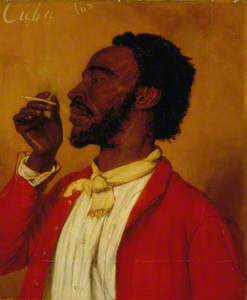

This second work is called The Pipe of Freedom. It shows a former slave in the southern United

The posters in the background give a bit more context to the work, suggesting that it is more than just a figure study. The Emancipation Proclamation has been pasted over a yellow placard announcing a sale of slaves. In the proclamation of 1862/1863, American President Abraham Lincoln declared that the Union would ensure that ‘all persons held as slaves within any state... shall be then, thenceforward and forever free.’ It eventually came into force in December 1865, at the end of the American Civil War. The painting, therefore, celebrates the end of the conflict and the abolition of slavery in the United States. The torn poster on the right alludes to ‘St George – His Last Appearance’, referring obliquely to English influence on American emancipation.

The Pipe of Freedom was also submitted to the Royal Academy in

Smith also painted a smaller work called A Cuban Cigarette, which has a similar theme and composition to The Pipe of Freedom.

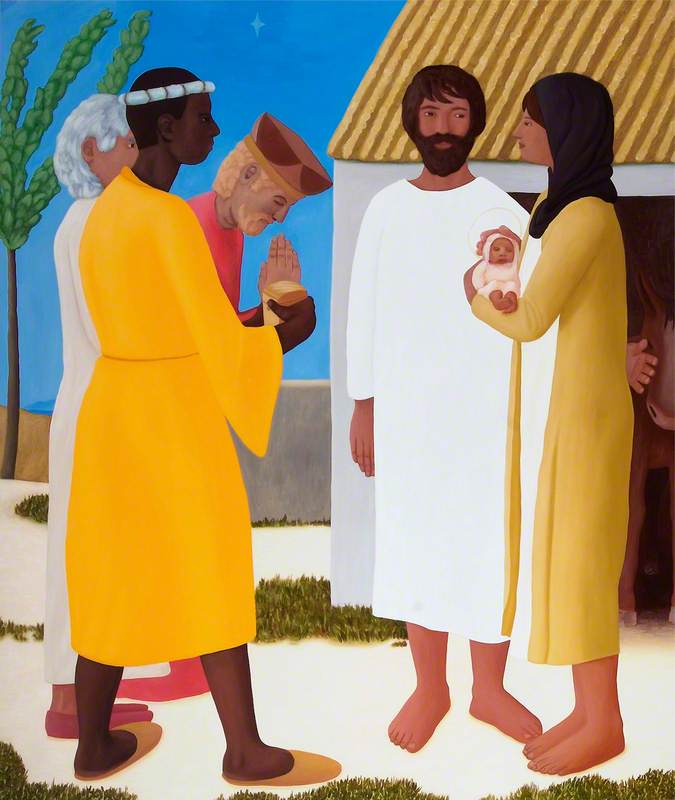

Painting black men and men of

Michael