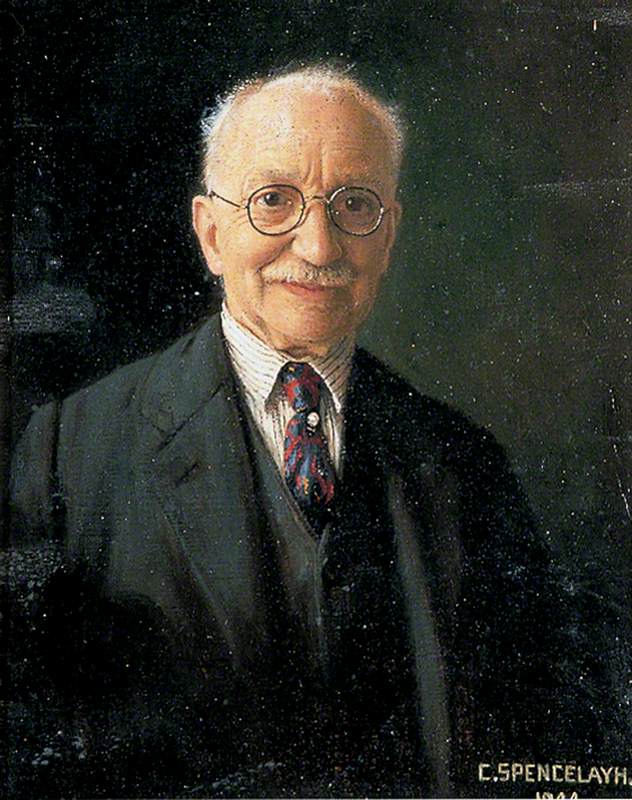

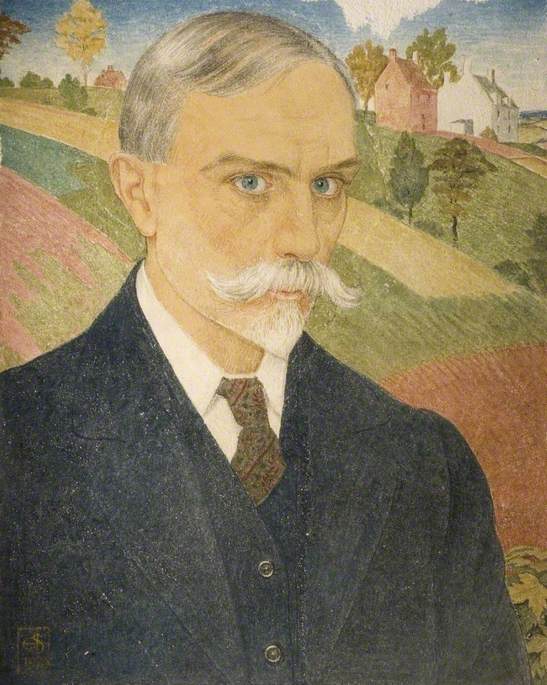

Little-known British artists don't normally find themselves in the national news, let alone at the heart of a Twitterstorm, so when I heard that William Rothenstein (1872–1945) was 'trending' back in October 2018, I was surprised. I've been researching the life and work of Rothenstein for over ten years now, and never seen his name in headlines. And I certainly never expected the subject of those headlines to be a group of three mural designs which spent much of the twentieth century in storage before their recent unveiling at the University of Southampton in 2014.

At the root of the controversy was a comment made by student union president Emily Dawes regarding the perceived inappropriateness of the 'mural of white men' displayed in the university's Senate Room. Dawes identified the paintings as symbols of the patriarchy; others, however, focused on the fact that the subjects of her attack were also war memorials. A short debate ensued, containing some thoughtful responses, but swiftly petered out after the apology and subsequent resignation of Dawes from her role.

From my perspective, the news story was a useful piece of publicity for Rothenstein's art. Though images of the mural designs have been available on Art UK (along with over 100 images of Rothenstein's art) for some years now, they have received relatively little attention to date. This is not wholly surprising. As it happens, Emily Dawes was not the first person to cast aspersion on Rothenstein's memorial paintings at Southampton. When first shown at the Royal Academy in 1916, they were met with general apathy and, as far as I know, were never again exhibited in the artist's lifetime. In 1959 the artist's son John gave the paintings to the University of Southampton where, again, they failed to attract serious attention until their re-instalment in 2014.

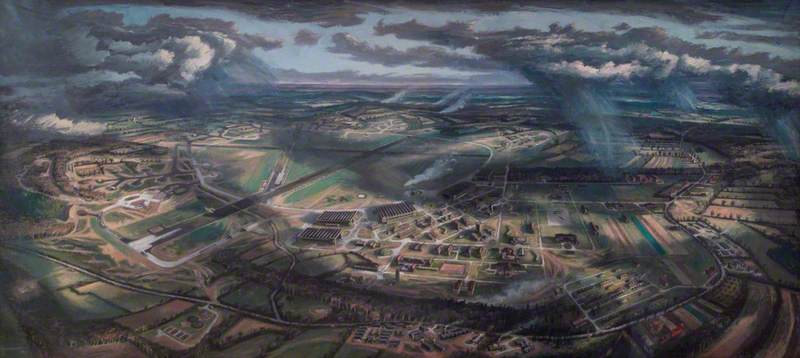

The first thing to note about the murals is that they aren't, strictly speaking, murals – but designs (or cartoons, as Rothenstein put it) for a set of murals that were never commissioned. In 1916 William Rothenstein's thoughts never strayed far from the subject of public art. This was the year he delivered his famous lecture, A Plea for the Wider Use of Artists and Craftsmen, subsequently published as a booklet, in which he called for British institutions (including universities, schools and town halls) to commission murals from the leading artists of the day. He hoped that the war, in particular, might kickstart a new era of public art, and offered up his memorial cartoons as a potential example of what might be achieved.

The inspiration for the mural designs came from a recent trip Rothenstein had made to Oxford, during which he had witnessed the conferring of degrees, which reminded him of the great processional frescoes of Renaissance Italy. This suggested to him the possibility of a symbolic wall painting, in which the recently fallen graduates of Balliol College, Oxford – which included Raymond Asquith, the then Prime Minister's son – would be reunited in a fictional degree ceremony.

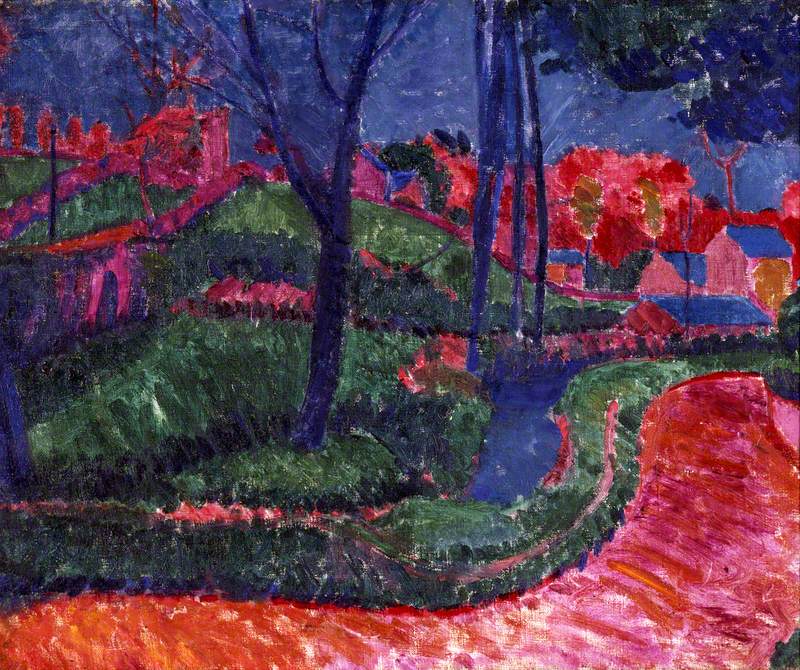

The designs show, in the two wings, two lines of young men, wearing academic gowns over their khaki, holding hands; and in the long central work, a procession of academics. For the young men, Rothenstein obtained permission from the parents of the deceased, including the Prime Minister himself, to work from photographs, aiming to capture, in his own words 'the peculiar radiance of their eagerness to serve in what has been to them a great cause'. The longer, central image was to suggest 'the might and dignity of later years'.

It was a worthy project, certainly, and one in which the artist invested much time and emotion. However, this didn't guarantee a smooth ride from critics, who largely dismissed it, thus ensuring that the designs would never be fully finished, or (at least for some time) publicly displayed. P. G. Konody, writing in The Observer, noted: 'Mr Rothenstein has set himself an impossible task; but even if due allowance is made for the insuperable difficulties he has scarcely done himself justice'.

A similar line was taken by The Manchester Guardian: 'The work has been done under great disadvantages', noted their writer, 'which probably accounts for Mr Rothenstein's failure to endow the effect with any charm of colour or mood or decorative processional quality'.

Rothenstein's friend, Eric Gill, put it most strongly in a letter, in which he argued that 'I don't like the frieze as a decoration because it seems to me that as pattern it is so largely spoiled by its portraiture [...] and as portraiture I don't like it because it worries me to see ordinary people walking in procession and yet all looking as if they knew they were having the portraits painted'. He concluded: 'Your theory that the painter should be a decorator is sound enough, but if he isn't one it can't be helped. I regret your excursions into decorating'.

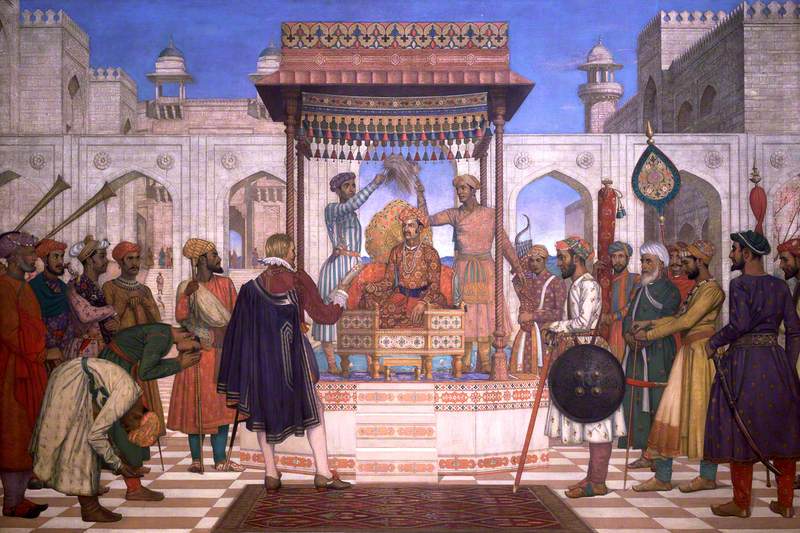

Image credit: Parliamentary Art Collection

Sir Thomas Roe at the Court of Ajmir, 1614 1925–1927

William Rothenstein (1872–1945)

Parliamentary Art CollectionEric Gill had a point. Rothenstein was trained as an easel painter, not as a muralist, and like many of his peers struggled to adapt to the latter role. Although he would later successfully complete a mural for St Stephen's Hall in the Palace of Westminster, he remains much better known for smaller-scale work, such as his 1899–1900 masterpiece The Doll's House.

The Southampton murals represent an interesting chapter in his career, however, to which fresh attention may now be brought, following their brief moment in the limelight.

Dr Samuel Shaw, co-founder of the Edwardian Culture Network