The invention of the hot-air balloon by the French brothers Jacques and Joseph Montgolfier in 1783 was a defining scientific and human achievement. Throughout history, the dream of flight had long stirred the human imagination, as evidenced by fanciful mythological tales and folk legends. Yet the creation of a huge balloon filled with hot air made such a dream a reality.

Shortly after its invention, the hot-air balloon was recognised by artists for its rich aesthetic and symbolic values, and as such has been a recurring subject in art ever since.

Lunardi's Second Balloon Ascending from St George's Fields, 1785 1785–1790

Julius Caesar Ibbetson (1759–1817)

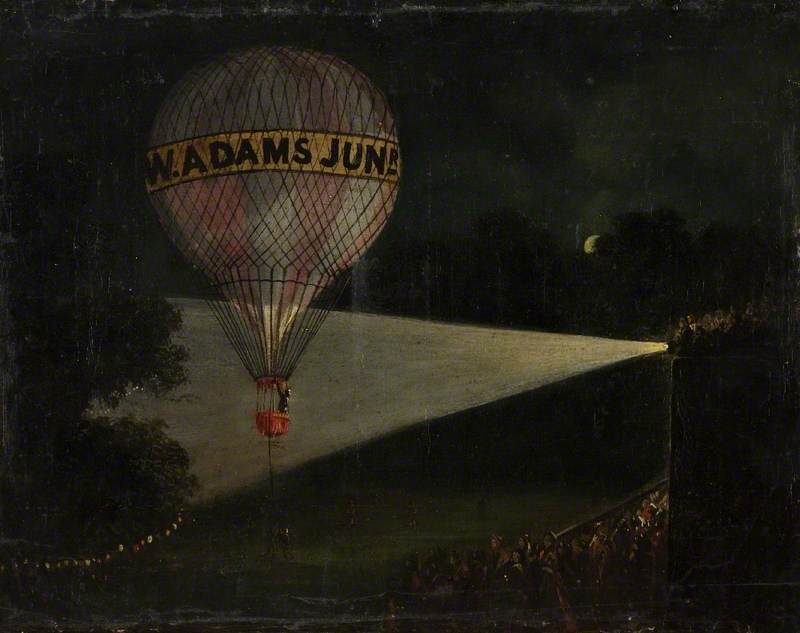

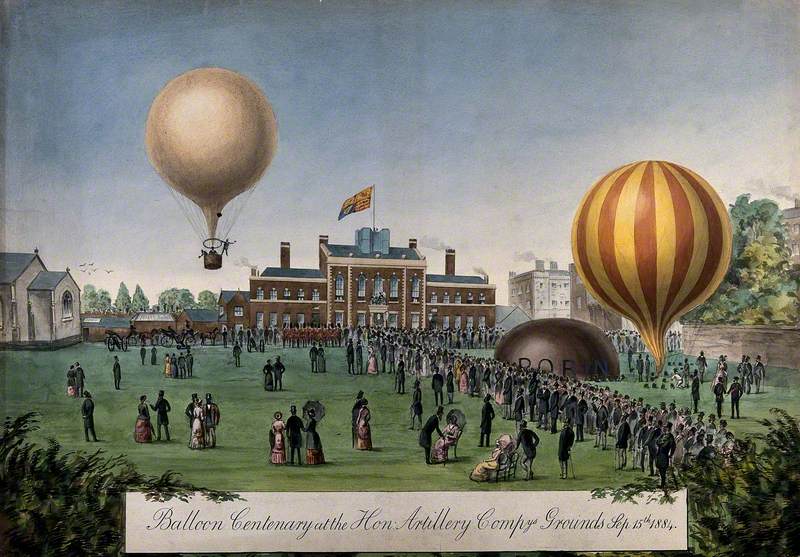

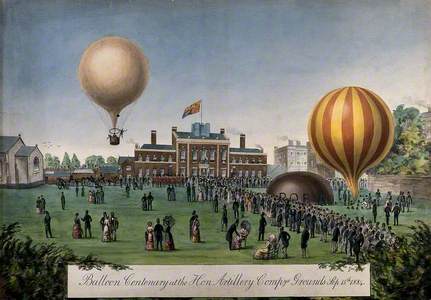

Science Museum'Balloons occupy senators, philosophers, ladies, everybody', so said Horace Walpole in response to the balloon phenomenon sweeping across Europe in the early 1780s. Public balloon ascents became the must-see events in the late eighteenth century. The excitement these ascents created is brilliantly captured in Julius Caesar Ibbetson's painting of an early public balloon launch.

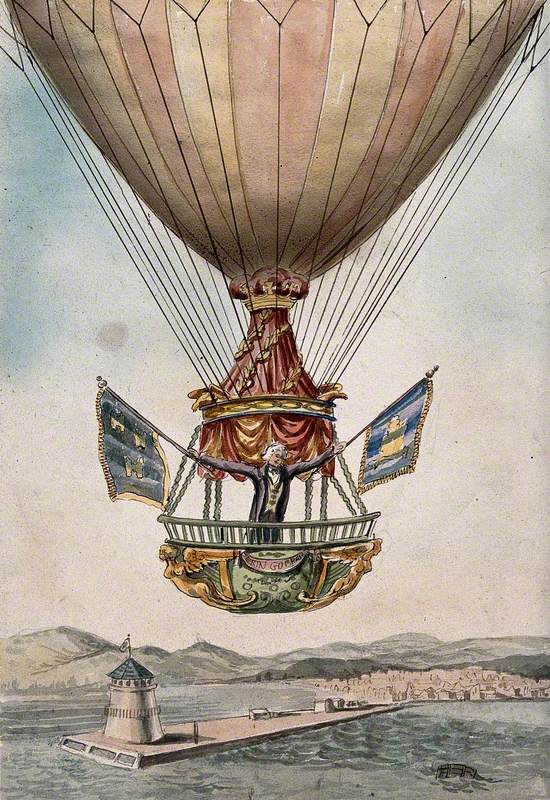

The painting shows a balloon belonging to the celebrated Italian aeronaut Vincenzo Lunardi being piloted by Captain George Biggin and the actress Letitia Sage. The vast, raucous crowd was a ubiquitous feature of early balloon launches.

Those involved in the earliest balloon flights became overnight celebrities. As the first British woman to take to the skies, Letitia Sage achieved a unique place in aviation history. Shortly after her aeronautical experience, she had her portrait painted, in which the balloon that made her famous can be seen floating in the background.

The prestige of being at the fore of ballooning is evident in an extraordinarily spirited portrait of Lunardi, Biggin and Sage by John Francis Rigaud. Although the trio never actually ascended together, they are shown in the gondola of one of Lunardi's balloons. Ever the showman, Lunardi waves his hat, while Biggin monitors their altitude and Sage gestures gracefully as they ascend skywards. The portrait captures the bravado, confidence and excitement that typified the dawn of the ballooning adventure.

Image credit: Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

Allegory of Wisdom and Science (frontispiece for 'Encyclopaedia Brittannica') 1798

James Millar (1735–1805)

Wolverhampton Arts and HeritageThe hot-air balloon was invented at the height of the Enlightenment and was regarded as a symbol of man's scientific conquest over the laws of nature. In James Millar's Allegory of Wisdom and Science, a hot-air balloon can be seen soaring in the distance.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

A Consultation prior to the Aerial Voyage to Weilburgh, 1836 c.1836–1838

John Hollins (1798–1855)

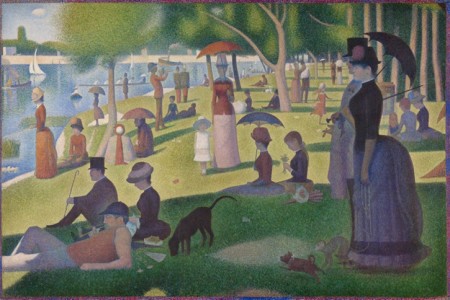

National Portrait Gallery, LondonIn the nineteenth century, ballooning continued to capture the public's imagination as aeronauts attempted ever-greater feats of flying. The seriousness of ballooning is evident in a group portrait by John Hollins. Here, a group of balloon enthusiasts, led by Charles Green on the right, are planning an ambitious balloon voyage that took place in November 1836 and went from London to Weilburg in Germany.

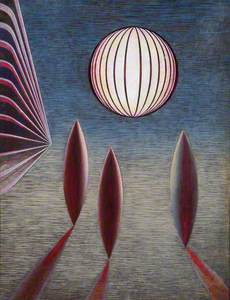

With the arrival of modern art, the hot-air balloon continued to be used by artists but largely for its aesthetic qualities. John Armstrong made the hot-air balloon's shape and structure a central feature in his highly modernist Composition: Balloon Abstract. Yet such was his interest in the balloon, he also included one in his surrealist-inspired Cophetua and the Beggarmaid.

© the artist's estate / Bridgeman Images. Image credit: The Ingram Collection of Modern British and Contemporary Art

Cophetua and the Beggarmaid 1953–1954

John Armstrong (1893–1973)

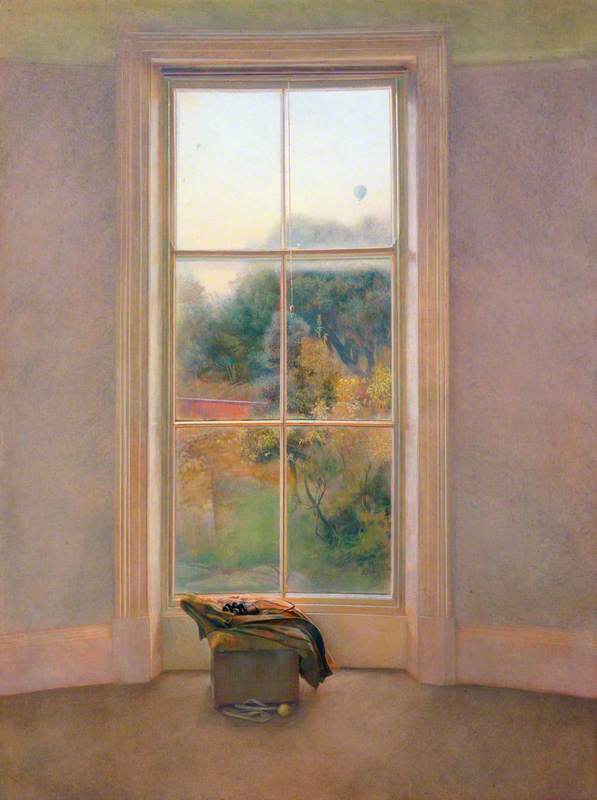

The Ingram Collection of Modern British and Contemporary ArtFor some artists, such as Michael Andrews, the hot-air balloon was not only visually appealing but also held a philosophical power.

Shadow has a wonderfully ethereal quality and shows only the shadow of a balloon as it glides gracefully above an elemental landscape. While reading about Zen Buddhism and psychology, Andrews noticed the phrase 'the skin-encapsulated ego', which he visualised as a hot-air balloon. Andrews believed a balloon rising above the earth best represented a personal quest for spiritual enlightenment.

A similar calmness of mood pervades David Tindle's Balloon Race, Clipston. This painting is a convincing reminder that seeing hot-air balloons gently traversing the sky remains a timeless and captivating sight.

2023 marks 240 years since the Montgolfier brothers unveiled their pioneering invention to the world. Today, we are just as captivated by a hot-air balloon sailing quietly across the sky as those earliest spectators were in the eighteenth century. The hot-air balloon will no doubt continue to beguile and inspire artists for many years to come.

Jonathan Hajdamach, independent art historian