In 1986 Victor Willing (1928–1988) had an exhibition that under other circumstances would have been career making. Championed by Nicholas Serota, then at the end of his triumphant stretch as director, the Whitechapel Gallery presented a survey of Willing's painting and sculpture, indicating the early promise that had come to fruition since his late 40s.

As it happened, Willing would only have one further show – the following year, with Karsten Schubert. By then it was over twenty years since he had been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. He held a brush only with great difficulty.

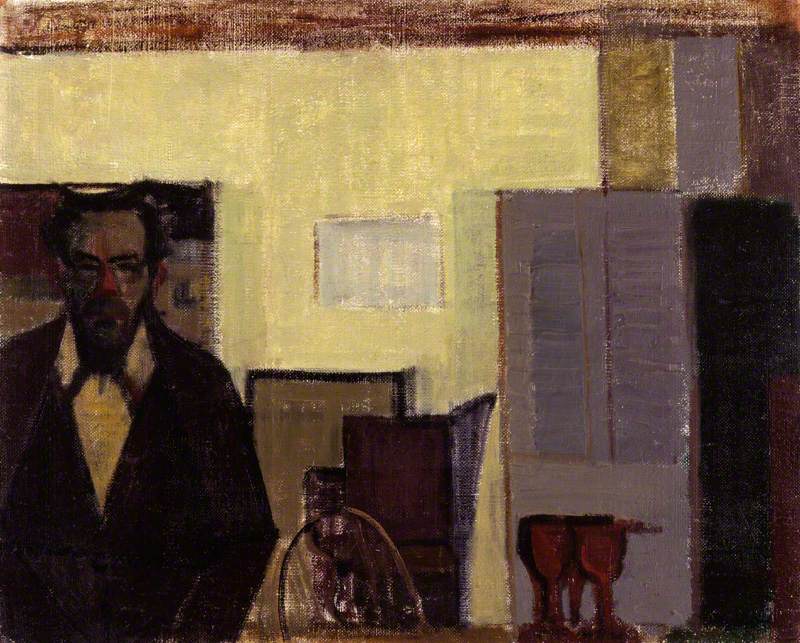

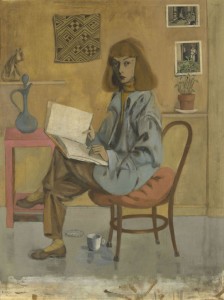

In Self Portrait at 70, he imagined himself as he might have looked ten years in the future. When he completed the portrait of an imaginary girl – Une Autre Femme – later that year he knew it would be his final painting.

Following Willing's death, aged 60, in 1988, there were no further exhibitions for over three decades. Then, in 2019, two at once: at Hastings Contemporary on England's south coast, and at Turps, a small London gallery associated with a painter's school and magazine. They coincided, too, with a broader resurgence of interest in British painting in the figurative-ish vein, both contemporary and modern. Certainly, the interest of Turps marked him as a painter to which others look.

Willing studied at Slade during the exacting tenure of William Menzies Coldstream (1908–1987). Charismatic and intellectually nimble, he distinguished himself within a brilliant generation that included Elisabeth Frink (1930–1993), Michael Andrews (1928–1995), Euan Uglow (1932–2000), and his future wife Paula Figueiroa Rego (b.1935).

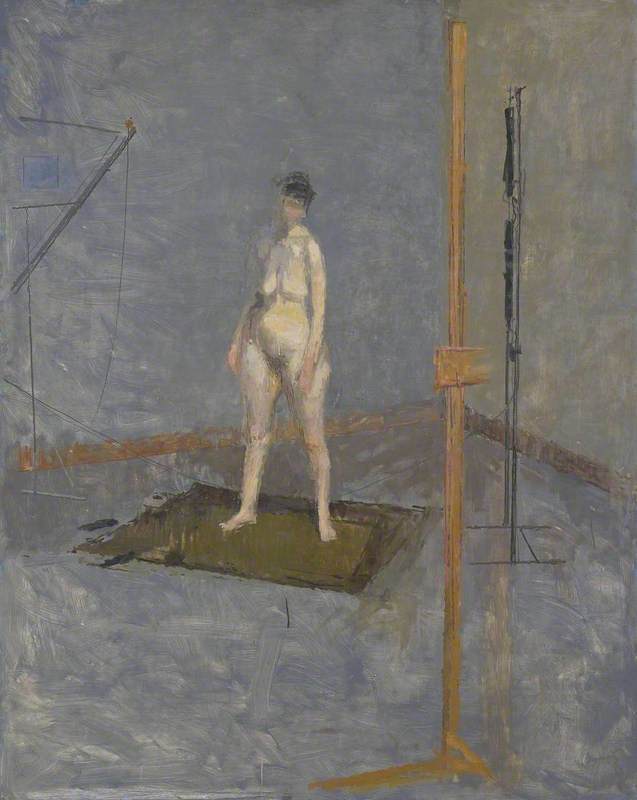

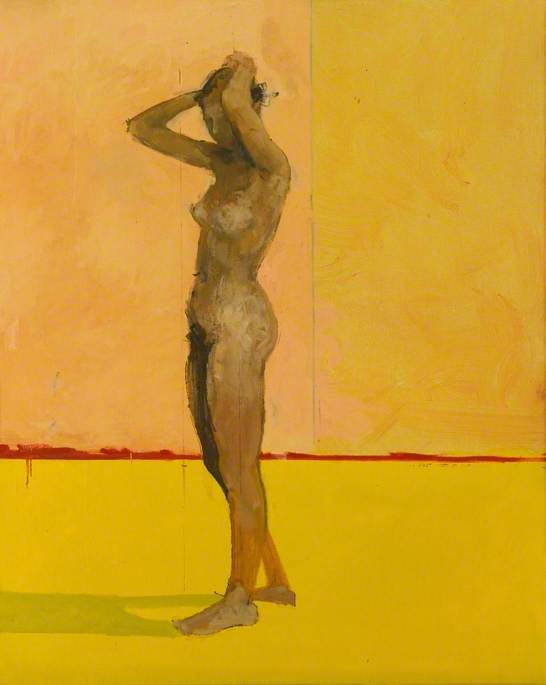

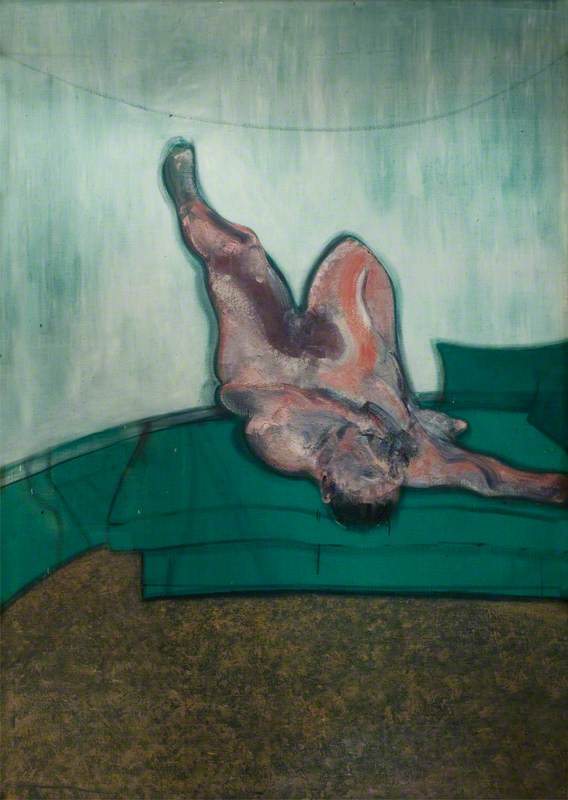

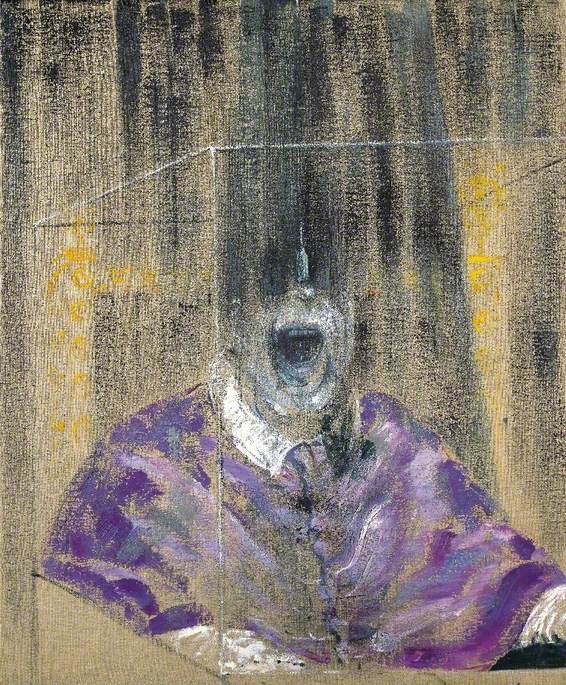

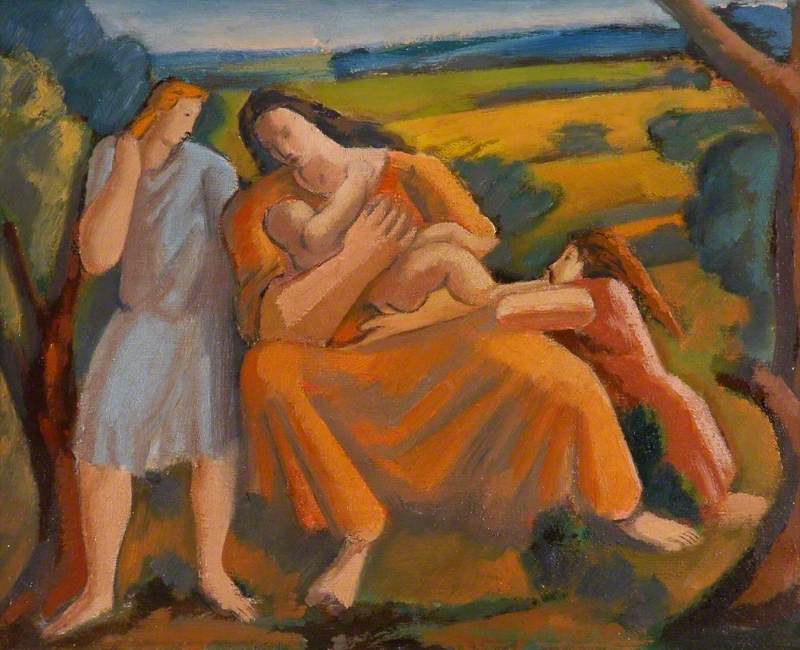

Coldstream taught as he practiced, dedicated to slow and meticulous observation from life. Willing complied in his own style, casting a sculptor's eye over bodies that he positioned at mid-distance within tightly contained spaces or against jarring colour, following the lead of Francis Bacon (1909–1992), who he admired. Two years after graduating his nudes (many of Rego) were shown at Hanover Gallery.

Perhaps that early success intoxicated? Despite his fascination with the mind and the painted world it might conjure, Willing kept returning obediently to life observed. It took another 20 years, amid the force of circumstance, for him to step away.

In 1976, having moved from Portugal to London, penniless, he started experiencing lucid visions, provoked perhaps by sleep deprivation or medication accompanying MS. The visions appeared still, coherent, mysterious, fully formed on the wall of his studio and he sketched them rapidly from memory.

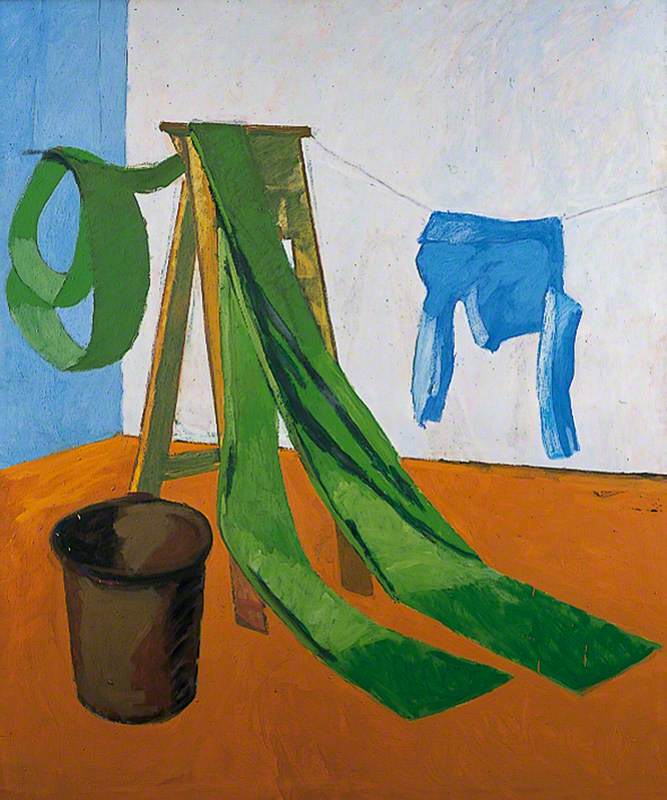

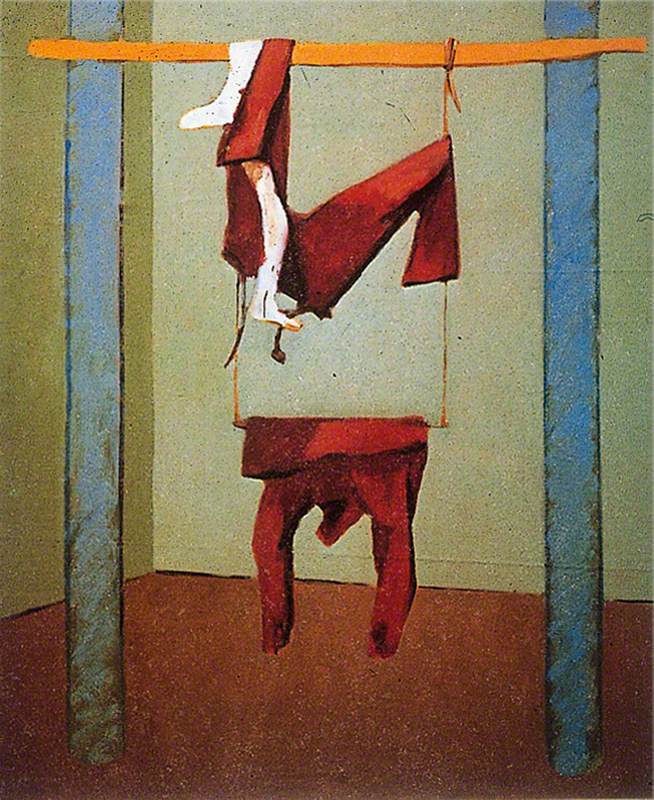

A symbolic vocabulary soon emerged: a chair; feathers; sprouting plants, clothes suspended from a line; a little sailing boat; two and three-dimensional geometric forms. As with his early figure paintings, all are tightly framed, mysterious objects contained by architecture, like history paintings denuded of heroes.

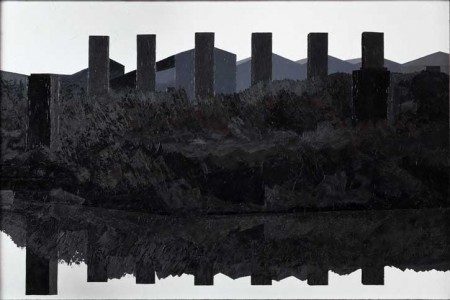

The paintings he created from 1976 were quite different from the figures that had gone before, though Willing's soft style, prioritising precisely modelled form over surface detail, endures. This late series was not without precedent: as early as 1956, after moving to Portugal, Willing started to explore looser, more abstract picture-making.

In Lech a sickly, fleshy long-necked form against a sticky puce recalls a headless sibling to Bacon's Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944).

Many years later, Nicholas Serota was surprised to discover the 'striking images' of these earlier paintings – among them Winter Machine (1956) which he described as 'a powerful and original painting that hovers between figuration and abstraction.'

Yet Willing was dissuaded from this path by a contemporary, who counselled he return to the more commercially palatable Slade style. A psychoanalytic inflection dominates the earlier visionary paintings.

The magnificent triptych Place (1976–1978) sets his empty chair and bag within a cabana, isolated in a broad blue room. The red chair reappears in the more claustrophobic Knight Errant (1978) set between a gas bottle and an electric heater, with a shirt hanging from a screen.

As a child, Willing's mother had once hung him by his braces in a cupboard – an association that fed into the repeated imagery of suspended garments (see Swing, 1978, below), though Icarus and the invisible man are there too.

Later paintings, such as Callot: Fusilier (1983) explore more formal, sculptural issues, stacking cubes, rods, spheres and a horses tale in a precarious equilibrium. This is one of a series dominated by an atmosphere of teetering balance that nod in title to Jacques Callot's Les Grandes Misères de la guerre (1633).

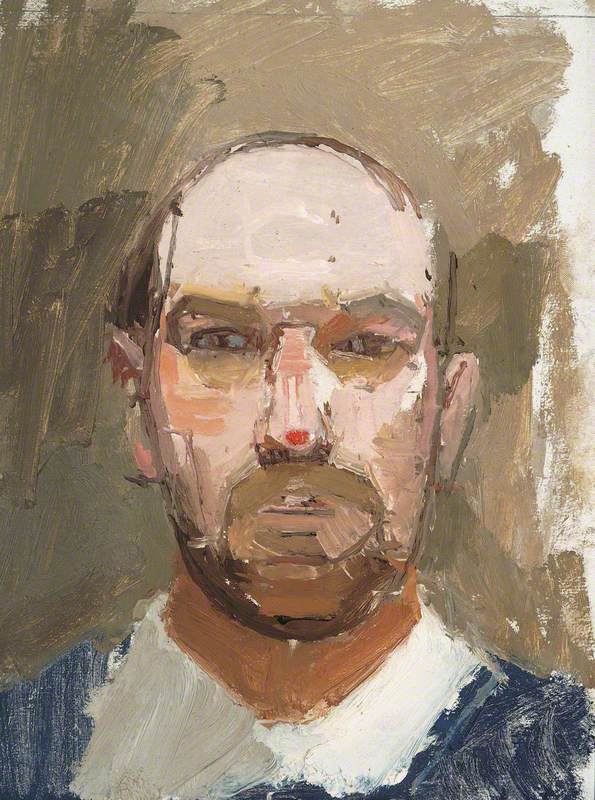

His mobility much reduced, Willing made a series of painted heads with the assistance of Lila Nunes (she has since worked closely with Rego). Willing compensated for his ebbing dexterity with humour. The comic irreverence of these final works casts the paintings that preceded them in a more playful light. Willing's visionary paintings have much, still, left to yield.

Hettie Judah, art critic

A version of this essay first appeared in The Art Newspaper. The exhibition 'Victor Willing: Visions' was on at Hastings Contemporary between 19th October 2019 and 5th January 2020.