'Will you have a cup of tea?' is the ubiquitous question made famous by Mrs Doyle of the Father Ted TV series. It is offered as the ubiquitous salve: you'll feel better after a cuppa.

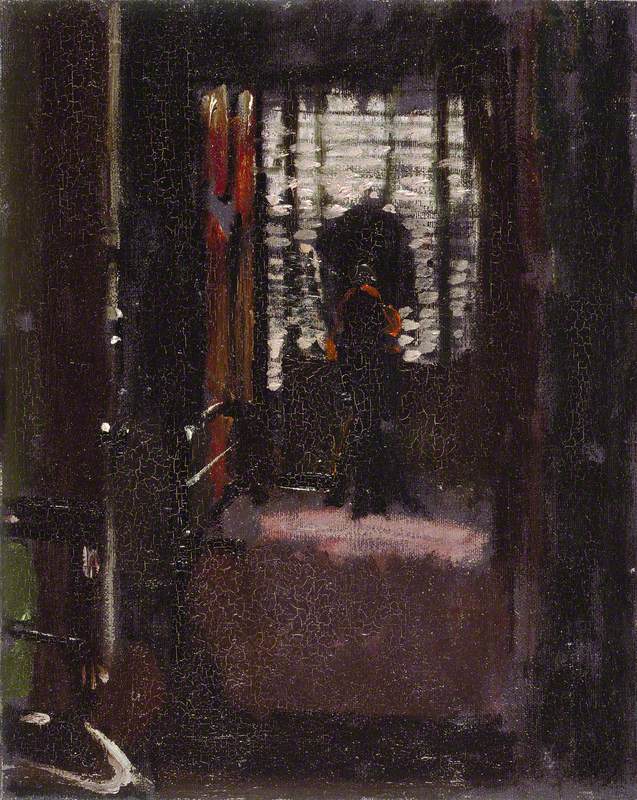

Let's take a look at Walter Sickert's A Cup of Tea, in the collection of The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology in Oxford, thought to represent Mrs Barrett.

The cup of tea signifying a contemporary relaxed social scenario supersedes the more formal eighteenth-century gatherings of the upper-middle-class nouveau riche described in earlier narrative paintings. These works, known as conversation pieces, were created by painters such as Highmore, Hayman, Van Aken and Hogarth, and used the 'event' as an excuse to set the scene of detailed recordings of the trappings of wealth – and therefore social status.

Here living offspring prove succession, inheritance and the potential of the educational Grand Tour. Money indicates success and the ability to afford afternoon tea in porcelain cups served by maids. Participants dress for their part in appropriate fabrics (silks, crepes, clean linen) and are portrayed contained in spaces that reflect the comforts of the time.

In Hogarth's The Strode Family, painted around 1738, the tea caddy is placed on the floor near to the mistress of the house, similarly positioned in Van Aken's An English Family at Tea.

These tea parties symbolised genteel society.

Thus, the Tyers family drink it and so do the Shudi family.

Turning back to the Sickert work, although Mrs Barrett shares the same beverage, she is lost in thoughtful contemplation and the mucky splotches of Sickert's basement world. The tea here is the excuse for paint and atmosphere. It is a kind of twentieth-century riposte to the concise and colourful world of Hogarth and Tuscher.

Sickert employs his characteristic dull pink and shades of taupe and verdigris. His visitor lurks in the gloom but fills the void with her substantial presence. Her pose a balanced diagonal; she is between a kind of sofa-seat, sitting sideways on the chair, her back leaning against the wall and so is boxed in against the table. She nurses her cup with her left hand and smokes with her right. She is perfectly ensconced in the space.

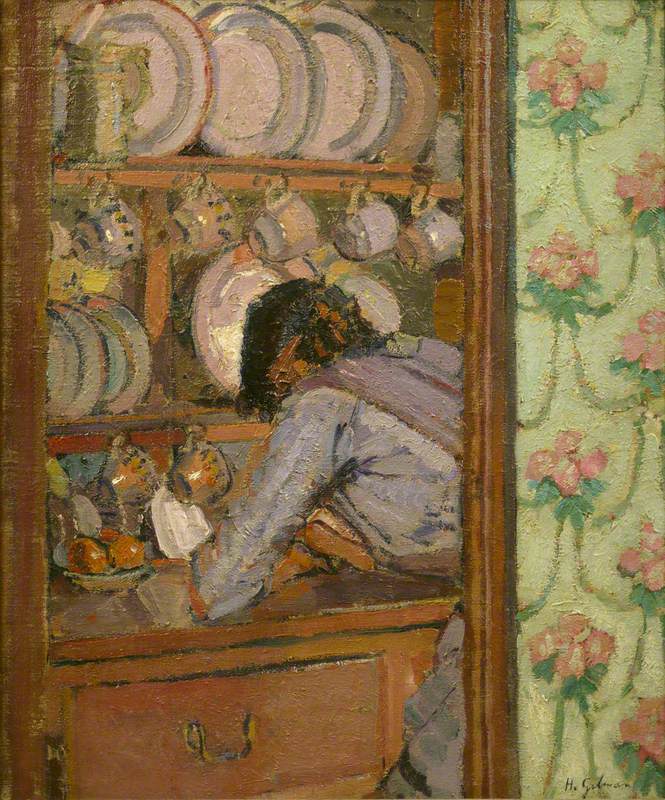

This modest painting does many things. It appears slight and inconsequential but it tells of societal change. Like the eighteenth-century works, it records a relationship between sitter and painter as well as a room. This room contains other paintings, noted in a cursory manner, so that they appear to us as brief cyphers, rendering them like later expressionist daubings. Another version of this painting exists – Sickert made copies of his works, for example, The Brighton Pierrots. The Auckland version differs slightly and is even more abstract, particularly the head of the figure, with the viewpoint looking more from above.

The form and colour of the painted interpretations of paintings are important to the composition as, apart from the table, they hold the upper space, but as usual with Sickert, it is the brief indication of what is there that is important. He delights in suggestion and celebration of paint as living matter. We don't need to know exactly what they depict but only the roving forms within them.

Isolated, these reproduced works could perform as small abstract expressionist works. One wonders what Sickert would have made of Rothko, et al., and their desire to allow the paint itself to constitute the reason and subject matter of an artwork.

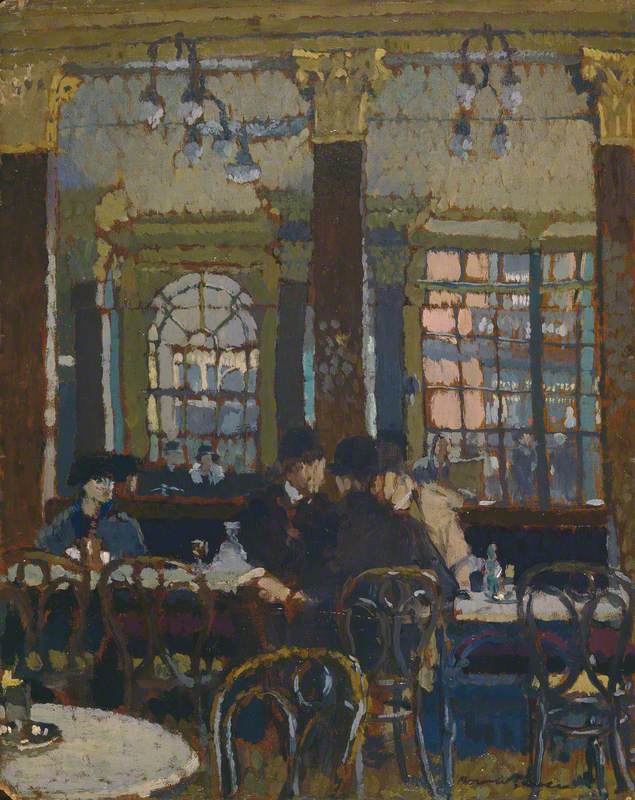

Sickert's focus is on the visitor who has made herself at home. There is no ceremony here: this work is all about sorting out a painting problem – it remains low-key and familiar. His 1915–1916 rendering of a tea party with friends Hamnett and Kristian is more formal despite being relaxed.

The Little Tea Party: Nina Hamnett and Roald Kristian

1915–16

Walter Richard Sickert (1860–1942)

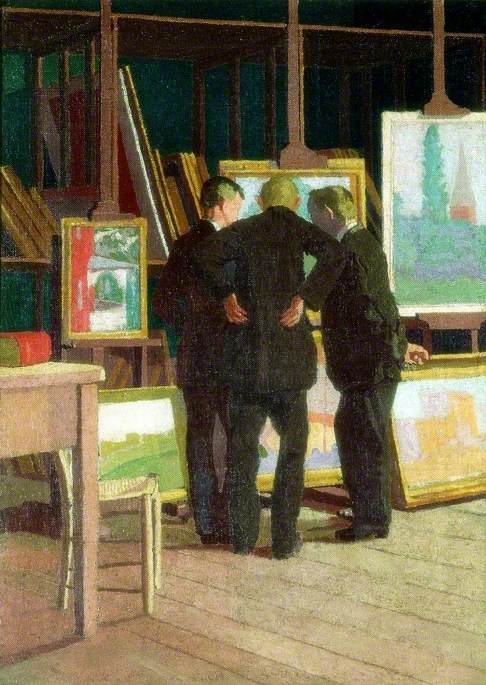

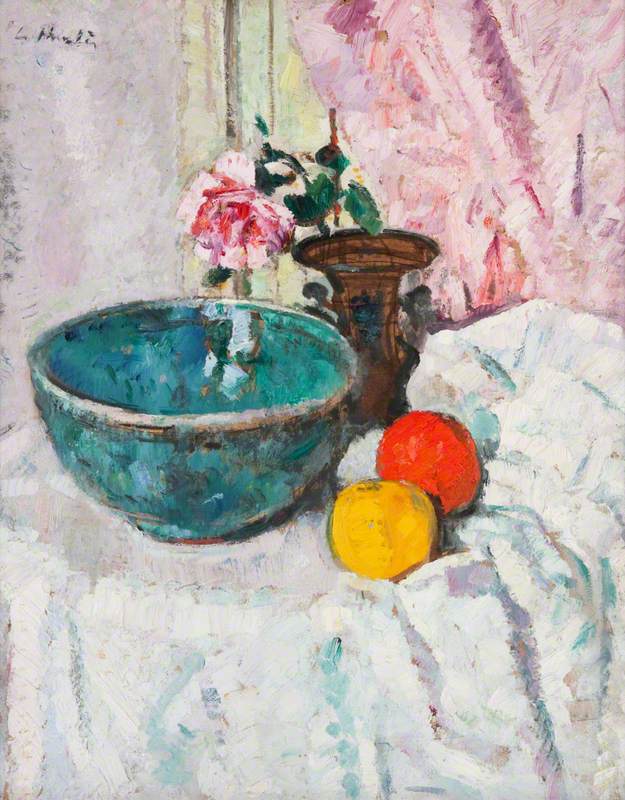

It is interesting to compare his works with this of a friend and quasi student, Ethel Sands.

Her work takes the table as a pivotal point in the event and, with her lighter palette, the whole room in which her two friends sit is brighter and lacks the rather lugubrious quality of Sickert's A Cup of Tea.

In Sickert Paintings (RA and Yale, 1992, p.5) Richard Shone quotes William Plomber*, who wrote aptly of the 'crystallisation of the unguarded and revealing moment' as being a hallmark of Sickert's work throughout his career.

Liz Rideal, artist and writer

*William Plomber, 'Mr. Sickert's Exhibition', Listener, 9th March 1938, p.256.