In 1918, the newly founded Imperial War Museum (IWM) took the groundbreaking step of commissioning the UK's first official female war artist, Anna Airy. The five large-scale canvases subsequently produced by Airy are some of the most powerful depictions of munitions production and other war-related aspects of heavy industry painted during the First World War.

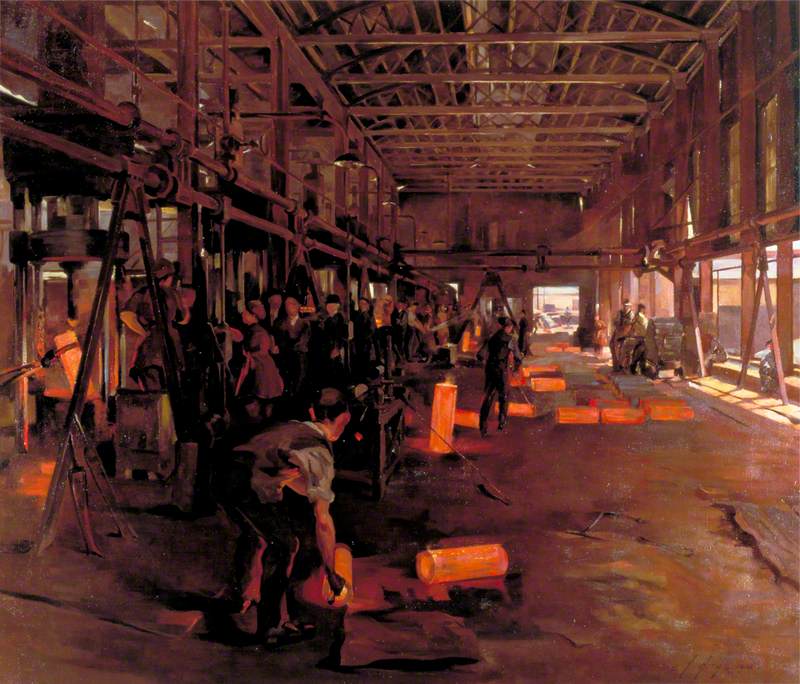

The 'L' Press: Forging the Jacket of an 18-Inch Gun, Armstrong-Whitworth Works, Openshaw

1918

Anna Airy (1882–1964)

Airy painted her canvases on site in difficult and, at times, dangerous conditions. As she describes:

'I'm at work at Hackney Marshes shell forge – am fast qualifying for the pit! They roll red hot shell cases in batches within 4ft. of me, to cool off! I can't describe the heat, but the general swelter and steam and dust and the swearing are going to make a ripping picture I think.'

Thus wrote Anna Airy, in a buoyant mood, to the art critic and journalist Robert Ross in early June 1918, five days after starting her first commission from the IWM. The finished work expertly depicts the searing heat of the shell cases as they come red-hot from the presses, the vast open space of the factory floor and the brilliance of both furnaces and the sun.

A Shell Forge at a National Projectile Factory, Hackney Marshes, London

1918

Anna Airy (1882–1964)

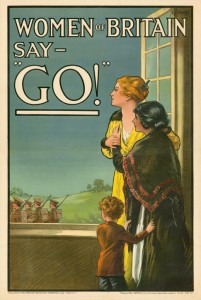

During the First World War, the British Government was at first slow to commission any war artists, male or female. The first official war artists' scheme was not set up until 1916, intended principally for propaganda purposes. The scheme experienced rapid development until, in 1918, it became the British War Memorials Committee (BWMC), which considered commissioning three women, Anna Airy, Flora Lion and Dorothy Coke.

More proactive in commissioning work was the Imperial War Museum which had been founded in 1917. The institution's less overtly political mandate was to collect art and other phenomena directly reflecting the last three years of conflict. Various commissioning committees were formed, including Sub-Committees for Munitions and Women's War Work.

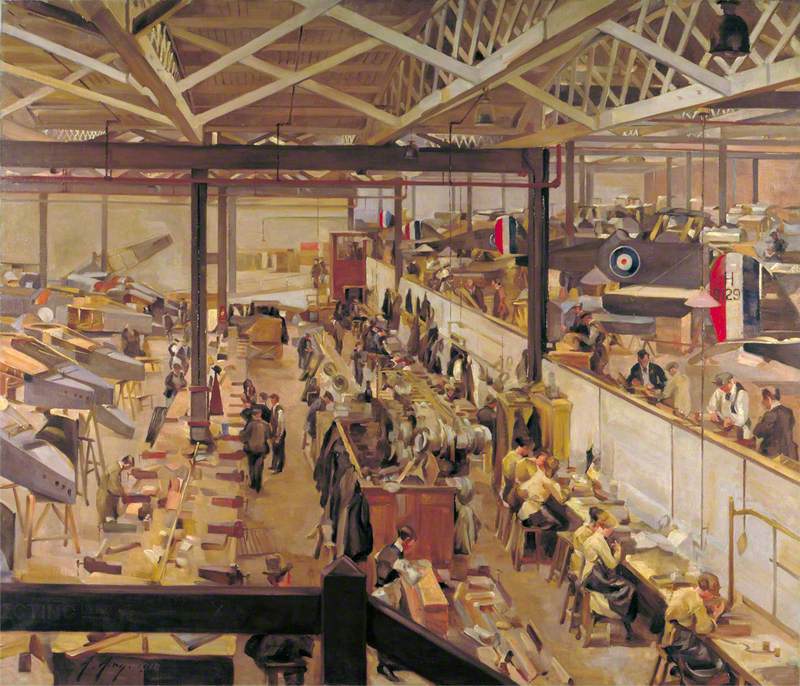

Airy's 1918 Munitions Sub-Committee commission was a major one: four seven-by-six-foot canvases. Two were painted in London, namely at the shell forge factory at Hackney Marshes and at an aircraft assembly shop at Hendon. For the latter, Airy chose an elevated vantage point which gives a detailed view of the various stages of the construction of the UK's first fighter aircraft.

Shop for Machining 15-Inch Shells: Singer Manufacturing Company, Clydebank, Glasgow

1918

Anna Airy (1882–1964)

Airy's additional commissions took her to Openshaw, Manchester and Glasgow. Once again, in her Glasgow painting of the 'Verdun' shop, she presents a panorama of the factory where the building's metal framing plays an essential role in the composition. The muted colours and subdued light filtering through the factory roof emphasise the grim nature of the work undertaken by the mostly female employees, dwarfed within this industrial environment.

Airy's commissions are housed in the collection of the IWM, alongside that of other women who 'painted' the First World War, and whose work has found its way into the Museum by other means – occasionally by purchase and more frequently by gift, as was the case with Flora Lion's Women's Canteen at Phoenix Works, Bradford. Here Lion depicts the busy canteen of a factory manufacturing seaplanes, shells and flying boats.

The scores of exhausted workers shown here emphasise the huge female workforce employed in the First World War munitions industry. Lion brings all her considerable skills as a portrait painter to the figures in the foreground, particularly the two central women, arms entwined. Surprisingly, this painting was rejected by the Munitions Sub-Committee, even after Lion believed that she had received a formal commission from the Committee's predecessor, the BWMC, and had devoted much time and expense in travelling to Bradford to complete the work and its companion piece, Building Flying Boats. In 1927, a patron who had bought both paintings gifted them to the IWM.

The official reason given by the Munitions Sub-Committee for rejecting Lion's paintings was that the IWM had insufficient funds to purchase all the works they might have wished to. Indeed financial constraints posed a major problem for the Women's Sub-Committee. Convened in the spring of 1917 to acquire material related to female contribution to the war effort, they had intended to commission work from both female and male artists but relatively few actual commissions resulted. One of their first was to Anna Airy, her fee matching the 280 guineas that she had received for each of her Munitions Sub-Committee paintings. The result was a dramatic painting of Women Working in a Gas Retort House, where gas was produced from heated coal.

Women Working in a Gas Retort House: South Metropolitan Gas Company, London

1918

Anna Airy (1882–1964)

Airy's painting illustrates the courage of women in applying all their strength to operating heavy machinery in what was considered to be the most dangerous work available to women during the First World War. Airy's use of chiaroscuro emphasises the Retort House's hellish atmosphere. The clouds of white smoke and orange flames leaping from the furnace on the left contrast effectively with the dark angular forms of the factory's machinery.

In contrast to Airy's substantial fees, Victoria Monkhouse only received £3 each for her series of small-scale watercolours showing women employed as bus conductors, drivers, window cleaners and other previously male roles, vacated by their serving in the armed forces.

A Bus Conductress

1919, pencil & watercolour on paper by Victoria Monkhouse (1883–1970)

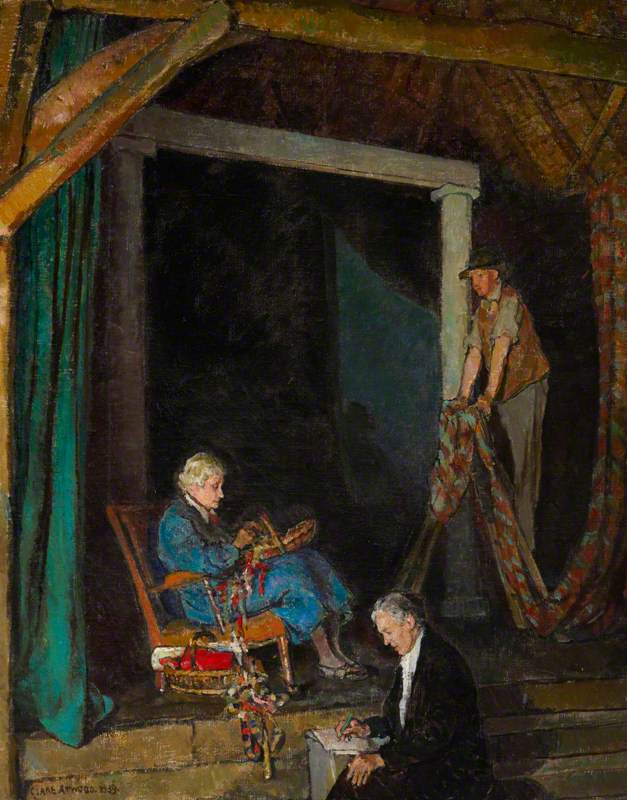

Clare Atwood fared better. From her, the Women's Sub-Committee commissioned two paintings, later purchased a third and accepted the gift of a fourth. One of the commissioned works showed Victoria Station, with groups of British soldiers being guided by women of the Women's Reserve Ambulance Corps. The work is probably set at dawn, when daylight begins to penetrate the arched entrance to Victoria Station, under which the forms of soldiers are huddled in almost complete darkness. These troops are either arriving on leave or departing for the front. The soldier, with his wife and three young children in the foreground, gives the viewer no clue as to which.

Probably Atwood's most famous piece, gifted to the IWM, shows Christmas Day at the London Bridge YMCA Canteen. This records the seasonal visit of the actress Ellen Terry (sitting by the table) and Princess Helena Victoria to soldiers. The space is crowded with soldiers awaiting their meal, but the painting's focus is on the two famous visitors and the women preparing to serve them.

Lucy Kemp-Welsh, the foremost painter of horses of her era, had unsuccessfully attempted to go to France to witness and paint equine employment on the Western Front. Instead, she was sent by the Women's Sub-Committee to Russell Park in Wiltshire where, during the First World War, horsewomen trained and prepared horses for military service. In the event, the Committee preferred another painting, The Straw Ride, to the commissioned one, which was rejected.

The Straw Ride: Russley Park Remount Depot, Wiltshire

1919–1920

Lucy Elizabeth Kemp-Welch (1869–1958)

The Straw Ride (eventually accepted as a gift) is indeed the more imaginative painting where the calm control of the riders is admirably contrasted with the raw power and energy of the horses, the central pair of which are dramatically silhouetted against a pale sky.

All works so far discussed depict the Home Front. The Women's Sub-Committee were also keen to acquire work from women who had, incidental to their work as volunteer (VAD) nurses or ambulance drivers, painted on the Western Front.

Olive Mudie-Cooke created striking images of wounded soldiers and devastated battlefields while working as a VAD driver. In 1919, the Committee purchased what has now become her most famous painting, In an Ambulance, which depicts an intimate moment as the VAD lights a cigarette for an injured soldier. In this watercolour, Mudie-Cooke has sensitively captured, in the momentary flare of light on their faces, this gesture of welcome comfort.

Mudie-Cooke's intimate work contrasts with Norah Neilson Gray's more formal painting of the Scottish Women's Hospital at Royaumont, one of ten hospitals that the Scottish Women's Hospitals set up in France during the First World War. Neilson Gray had herself worked as a VAD at Royaumont Abbey.

In 1920, the Women's Work Sub-Committee commissioned her, with a specific brief, to paint a work celebrating the work of the female doctor, Dr Frances Ivens. The result is perhaps somewhat idealised. There is no sign of injury or suffering here; instead, the work concentrates on the institution's cleanliness and order. Nevertheless, this was the painting's purpose: to demonstrate that women had been capable, during the First World War, of organising and running hospitals to the most exacting standards.

Neilson Gray's painting, as is the case with all the paintings featured in this piece, reflects the extraordinary contribution that women made on both the Home and Western Fronts during the First World War: vital work that changed forever society's previous rigid demarcation of traditional female and male roles within the workforce. Creating these paintings was also important for the careers of the artists themselves, giving a boost to their struggle to be regarded equally as serious professional artists as their male contemporaries, and with the resultant same access to exhibiting opportunities, membership of professional bodies and representation in public collections.

Alison Thomas, freelance writer and curator

Many of the works featured in this story are on display in the Imperial War Museum's new gallery space: the Blavatnik Art, Film and Photography Galleries, which open 10th November 2023