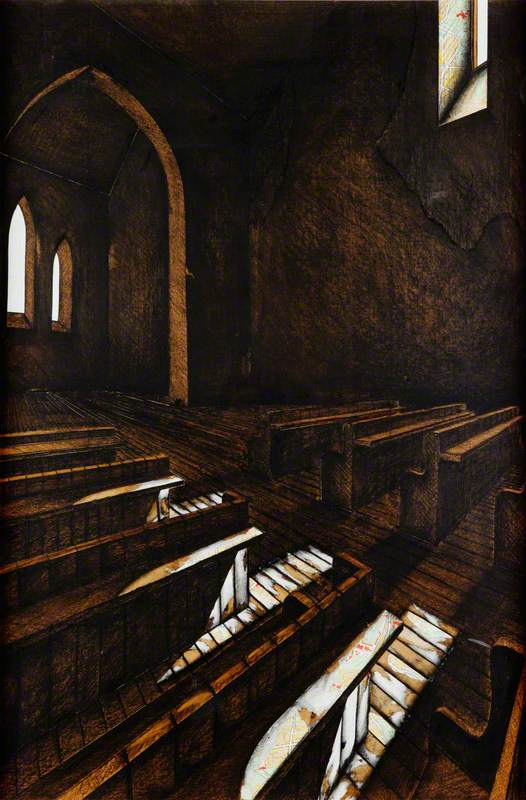

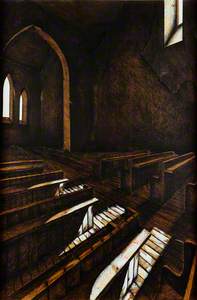

As humans, we can only make sense of the world around us in terms of our own experiences and emotions. This is what made All Will Be Forgotten so compelling to me.

The painting has a quiet and reflective atmosphere – as all churches seem to have – that captivated me immediately: I was able to step right in, tread quietly across the floorboards, and take a seat on a cold pew, sitting in between the ghosts of churchgoers from long ago, basking in the ethereal light that splashes onto the floor. I can almost see Chris Wilson setting up an easel in the corner, having snuck in to find solitude in the sanctity of the Church during the isolation of 1980s Belfast – even if it was spaces like these that polarised Belfast to begin with. Art can reconnect with us in new ways in new times, and it is this ambiguity that allows me to escape from the confines of my home in the January 2021 lockdown, and into the stillness of Wilson's quieter enclosure.

If I had discovered All Will Be Forgotten two years ago, it is likely I would have resonated with the religious symbolism. If I had discovered the artwork last year, maybe I would have been drawn to the reflective and tranquil atmosphere. But I discovered this work in 2021 – in the context of extreme isolation that the lockdown forced upon us, so a new interpretation of this artwork is inevitable.

But Wilson is not painting his response to the insular feeling reflected in Belfast during The Troubles. He is collaging it. It was only upon further research did I realise the splash of light that spilled across the artwork was in fact maps – maps of Belfast, that both divide and link the city, physically and psychologically. The work came to life all over again. This time, I could see a network of time and memories.

So, what connects maps of Belfast to an empty church interior? Conté (similar to graphite sticks) are used to build upon the map, increasing the contrast of the sharp light and murky dark, and therefore increasing the contrast of the projection of angular light into the church's gloom. It was these extremes, together in tension, that allowed Wilson to explore this sense of separation, through the division of light and dark, and interior and exterior.

Isolation. It is an overwhelming feeling in our current climate, but despite All Will Be Forgotten being made almost 40 years ago, we effortlessly reconnect with artwork in new times when our whole understanding of art is influenced by our lives and experiences. All Will Be Forgotten is a powerful title and reminds us how art exists in grey areas, and how – for many areas of life – there are no definite answers. I emailed Wilson to ask him where the inspiration for the titles comes from, and he explained that the titles are sourced from poetry books or hymns: 'They are deliberately ambiguous. I aimed to connect the image to ideas of the passage of time and that ultimately everything becomes a memory, a past event or time.' Does this mean that all being forgotten is such a terrible thing? Perhaps it is this that allows us to always find relevance and meaning in art – it has a lasting power.

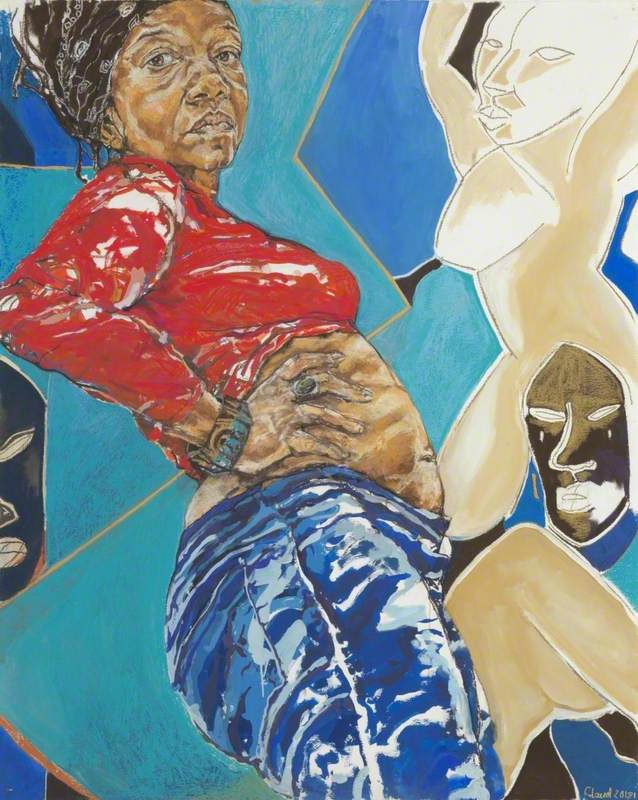

Hanifah Smith, second-place winner of Write on Art 2021, Years 12/13

Further reading

Slavka Sverakova interviews with Chris Wilson by email, February 2008