Since adolescence, my mother had told me to never to stay out too late, to always walk in groups, to always be careful of my surroundings. They are words every woman hears in her life. She follows universal rules set out to protect her on her streets, in the office or at home.

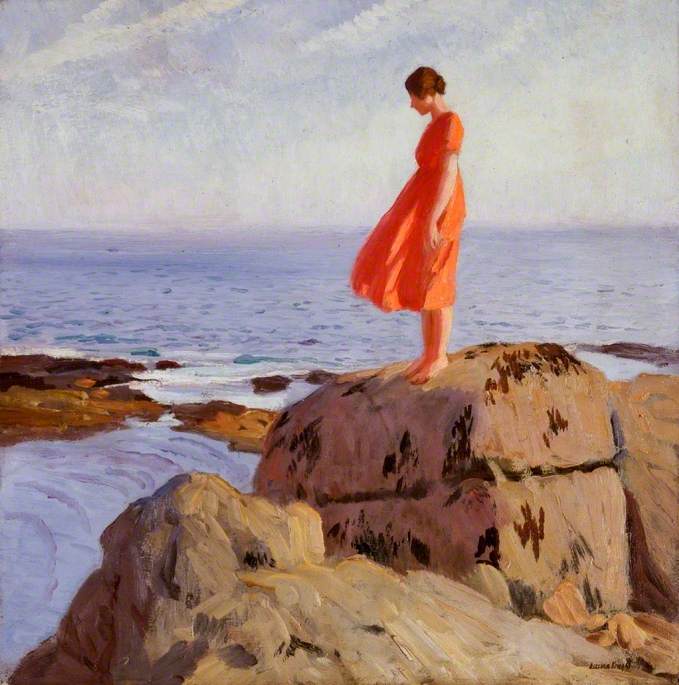

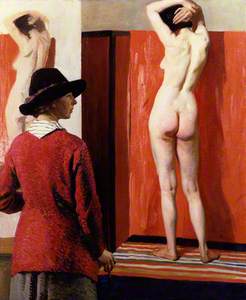

This sentiment has been reflected in art. Throughout history, depictions of women's bodies have been controlled by the male gaze. The man behind the canvas making art for the pleasure of men before the canvas has been herald as a genius for many centuries. Laura Knight's Self Portrait aka The Model turns this constant on its head.

Knight places herself with a nude model at a time when women were restricted access to a nude by the Royal Academy. The illuminated figure immediately catches your attention. Portrayed in contrapposto, the model resembles the sculptures of Polykleitos and portraits of the Italian renaissance. Knight actively carves a place for herself alongside the old masters. Unlike in Manet's Olympia, the warm gaze of the female artist subverts the voyeuristic eyes of the male artist. Her gentle brushstrokes follow the figure of a naked women, relaxed in her disposition, humanising the often-fetishised female nude. The bold and warm colours escape the flat surface to surround the viewer with the comforting and inviting ambience created by the woman in charge of the painting.

Knight captures herself, in profil perdu, dressed in a simple knitted cardigan, her gaze fixed on the model. She contradicts the often-passive role women play in artwork by placing herself, a working woman, as the orchestrator of the piece with absolute power.

Knight's open depiction of the normality of and between women was previously unseen. For her intrepid artwork, Knight was accosted by critics and subjected to disapproval by the public. A writer in The Telegraph called the artwork 'vulgar' and 'dull' when it was first displayed. It was rejected by the RA and contention around it continued when Laura exhibited the artwork again under a different name. It was retained by Knight until she died in 1970; a year after which, in 1971, it was bought by the National Portrait Gallery where it is now displayed. The seemingly conventional painting surpassed the public reactions to avant-garde artists. The simple act of painting a naked woman was more contested than the Dada art that succeeded it and the Impressionist paintings that preceded it.

The piece is unlike any other depiction of female nudity I have encountered throughout art history. Described by the National Portrait Gallery as 'a bravura statement about the ability of women to paint hitherto taboo subjects on a scale and with an intensity, that heralds changes', this simple artwork drew me in with its powerful statement. I became fascinated by Knight's career which captured human normality, from naked bodies to marginalised individuals.

Now, in 2022, more than 100 years after this painting was first exhibited, and women's autonomy is still a contested issue. Institutions and men in authority still have a huge control over women's bodies. Recently, the overturned Roe v. Wade legislation in America, prohibiting the protection of abortions has been a horrifying step backwards into the past. In 2021, Sarah Everard's death was a heartbreaking reminder of the lack of safety available to women.

Are women not allowed a right to their own body? Can they not exist without fear? The world is a stifling place for a woman, blind to age and location. Laura Knight's self-portrait is a stark reminder of the lengths we have come and the steps we still need to take to ensure the welfare of all women.

Tavishi Gupta, first-place winner of Write on Art 2022, Years 12/13

Further reading

The National Portrait Gallery's description of the painting

'The life less ordinary of artist Laura Knight', The Guardian, 14th October 2021