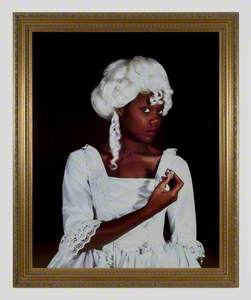

'Survival is visibility.'

These words, articulated in Sulter's Zabat narratives, almost appear palpable through the subject's piercing gaze. Perhaps the arresting authenticity in her expression – in the snarl that so gently lifts the corner of her mouth – is no coincidence. The model Sulter has chosen to photograph is Delta Streete, a performance artist, acclaimed for her installation The Quizzing Class. In this installation, Streete explored the relationship between white mistresses and their slaves – a theme Sulter appears to explore in this piece.

Terpsichore

(from the series 'Zabat') 1989

Maud Sulter

Here, Streete appears as Terpsichore, the muse of dance, embellished in a dress she crafted herself. A dress that would have been exclusive to the upper echelons of eighteenth-century European society. A dress that would not have been fit for a woman like her.

And yet, what do we mean by a woman like her? What is it about the portrait that is so subversive, so unconventional? Sulter seeks to draw out these uncomfortable questions from the viewer, compelling us to interrogate the absence of Black women in aristocratic art. Such an absence is deeply unsettling to think about, emphasising Sulter's point that 'Black women's contribution to culture is so often erased and marginalised.' However, it appears half-Ghanaian Sulter seems to push against this enforced norm, wanting to 'put Black women back in the centre of the frame'.

And so she does, through Terpsichore. Streete glares, unsmiling, directly out to the viewer. Her probing eyes trace my tentative steps through a traditional, three-quarter head pose. However, this sense of tradition is undermined by the object Streete carefully holds. Not a flower or a sheet of music... but fool's gold. A symbol of gold mining and slavery, it stands in stark contrast to the enslaving-class attire Streete is adorned in. And so, symbolically, the bound are unbound through Sulter's masterful eyes. The very thing that once tied black women to their masters has been reclaimed with an inspiring vigour.

Sulter's choice of photography as a medium adds another dimension of complexity to the narrative the piece evokes. In seeing the absolute humanness of Streete, my breath cannot help but hitch. The clarity of her form, the artificiality of her wig and clothing, is a far cry from the wispy, idealised airbrushing of typical eighteenth-century court portraiture. She is real. She is every bit as real, if not more, than the uncanny ivory faces that gaze at me with unassuming eyes.

History is not made for women of colour.

As Alice Walker articulates, 'As a Black person and a woman I don't read history for facts, I read it for clues.' Sulter takes these clues, of the unsung contribution women of colour had in steering the course of culture, and valiantly brings them to the forefront of her pieces. She deftly explores the erasure of Black people in their contribution to European culture. Whether that be in classical history, after the destruction of the Great Library in Alexandria, or the servants brought back to England as a result of chattel slavery, Sulter seeks to do one integral thing. To represent.

Ironically, it was Vigee le Brun's Marie Antoinette en chemise which brought me to this piece. The flamboyant varnish of the Rococo, its promises of grandeur, instantly dissipated the moment I laid eyes on this piece. Not because Streete wasn't grand. But because that veneer of artifice seemed more ingenuine than ever before.

I step out of Edinburgh's City Art Centre, the shadows of my ancestors fade into the morning light.

Nilla Feron Clark, second-place winner of Write on Art 2023, Years 12/13

Further reading

Beth James, 'Rendering the Invisible Visible: Maud Sulter's Zabat', HASTA, 2022

Marie-Luise Mayer and Donata Miller, 'Zabat' – photographs by Maud Sulter', V&A