Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery (1887–1976), 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, GCB, DSO

1952

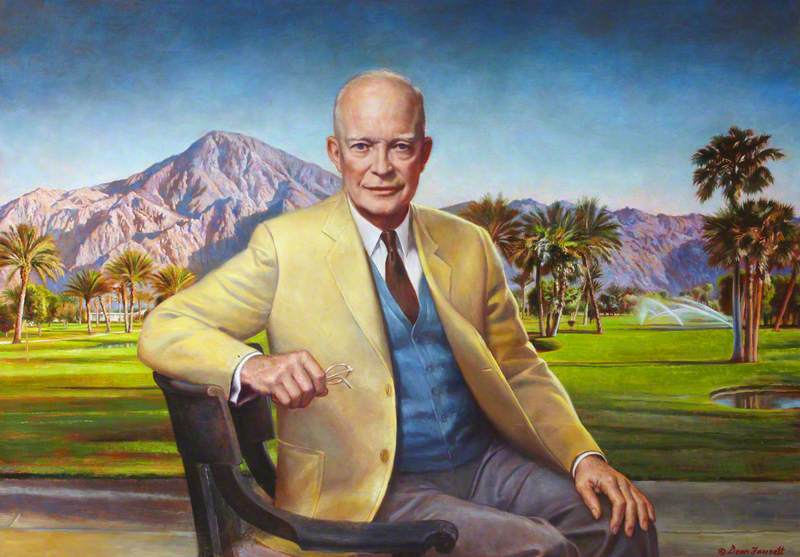

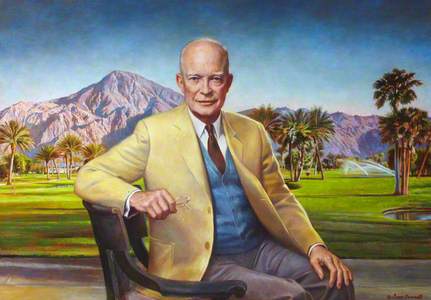

Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890–1969)

This portrait of Field Marshal Viscount Montgomery of Alamein (1887–1976) was painted in the spring of 1952 by General Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890–1969). Eisenhower was Supreme Commander Allied Forces Europe until his resignation on 31st May of that year. Montgomery was Deputy Supreme Commander. On the back of the portrait, Eisenhower wrote: 'To my friend Monty from Ike'.

It is rare for one general to paint the portrait of another general. It is even rarer for the artist in question to have become President of the United States a few months later. And when remembering the extraordinary tensions between the two men during some of the most critical moments in our history, the very existence of the portrait is even more striking.

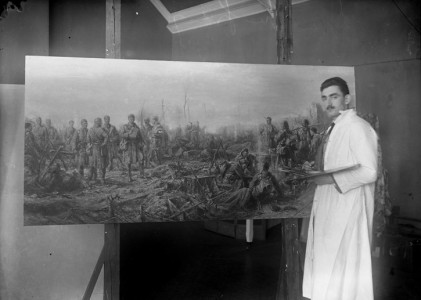

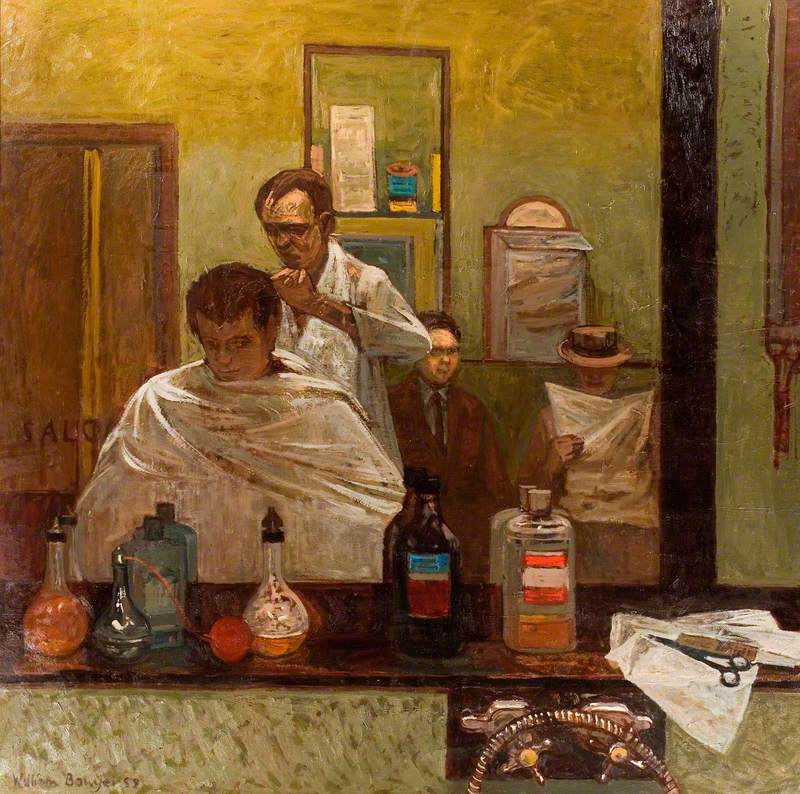

General Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890–1969)

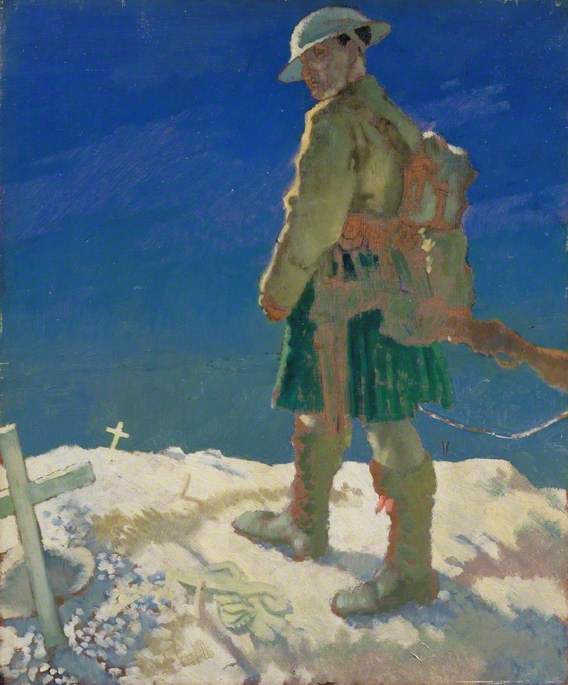

1943

Henry Marvell Carr (1894–1970)

On their first meeting, General Sir Bernard Law Montgomery ticked off General Eisenhower for smoking in his presence. Eisenhower, who had already been earmarked as the future Supreme Commander for Allied forces in the European and North African theatre, accepted the reproof with his famously amiable smile. Monty's verdict on his Supreme Commander, 'Nice chap, no soldier', was typical of his breathtaking egotism. Monty ranked himself with the greatest captains of history, such as Marlborough and Wellington. American generals, on the other hand, did not share his assessment.

Montgomery was incapable of sensing the emotions of other people. He was convinced that his American counterpart, General Omar N. Bradley, admired and liked him, when in fact Bradley loathed him. On 1st September 1944, during the great breakout from the River Seine across eastern France, Montgomery's promotion to field marshal was announced. General George S. Patton wrote to his wife that day, 'The Field Marshal thing made us sick, that is Bradley and me'. A field marshal was a five-star general, while Eisenhower, their superior, still had only four stars. Even a number of senior British officers thought that Winston Churchill had made a grave mistake. Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay, the Allied naval commander-in-chief, wrote in his diary: 'Monty made a Field Marshal. Astounding thing to do and I regret it more than I can say. I gather that the PM did it on his own. Damn stupid and I warrant most offensive to Eisenhower and the Americans.'

Field Marshal The Viscount Montgomery of Alamein and Hindhead (1887–1976), GCB, DSO

1944

Herbert James Gunn (1893–1964)

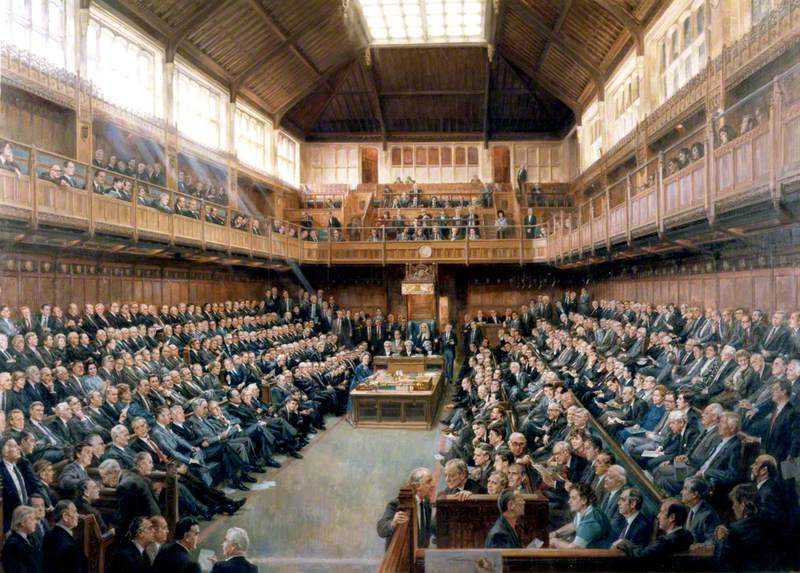

By a curious coincidence, both Montgomery and Bradley, the two Allied army group commanders of the Normandy campaign, happened to be sitting that day for portraits at their respective headquarters. Bradley near Chartres was being painted by Cathleen Mann, who was married to the Marquess of Queensberry.

Despite the messages of congratulation that morning on his promotion, Montgomery was in such a bad mood that he refused to meet his host, the

Field Marshal Viscount Alanbrooke (1883–1963)

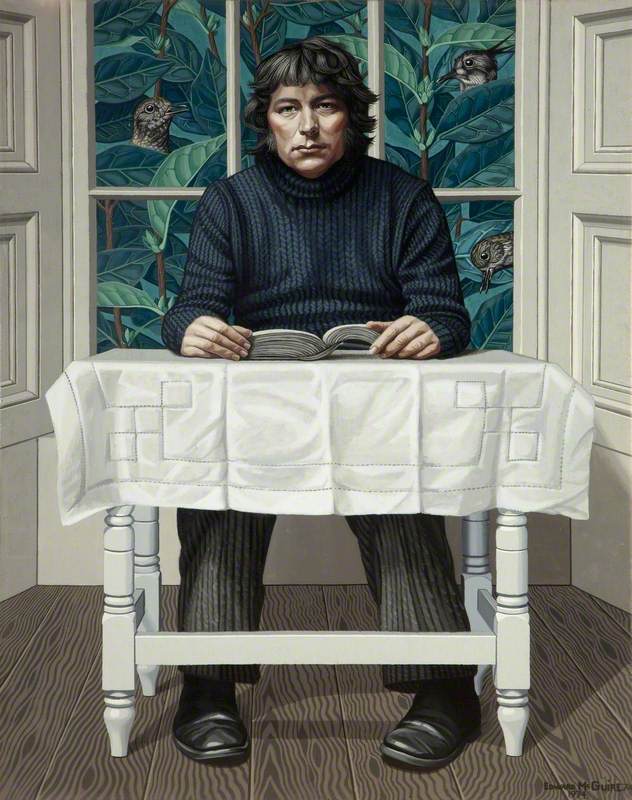

1957

Patrick Edward Phillips (1907–1976)

Relations between Montgomery and Eisenhower did not run smoothly, despite every effort on the Supreme Commander's side to humour his difficult subordinate. The worst period came in the wake of Montgomery's disastrous press conference in January 1945 when he implied that his command over American formations had won the Battle of the Ardennes. The British were warned that no American general would ever agree to serve under Montgomery again. So, Eisenhower's portrait of Monty with friendly dedication seven years later was a very generous gesture. But the peace did not last. In 1958, six years after the portrait, came the 'battle of the memoirs', with Montgomery's self-serving autobiography. Eisenhower was so furious at Montgomery's criticisms and claims, that at the end of his life he exploded to Cornelius Ryan: 'He's a psychopath, don't forget that. He is such an egocentric... He has never made a mistake in his life.'

The oil on canvas portrait of Field Marshal Montgomery by Eisenhower is currently housed in the British Embassy in Washington DC, USA. It belonged to Montgomery himself before it was sold through Sotheby's London in 1969 where it was purchased by the United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom, Walter Annenberg. In January 1970, Annenberg presented the portrait to the Department of the Environment. Today it belongs to the UK's Government Art Collection.

Sir Antony Beevor, historian